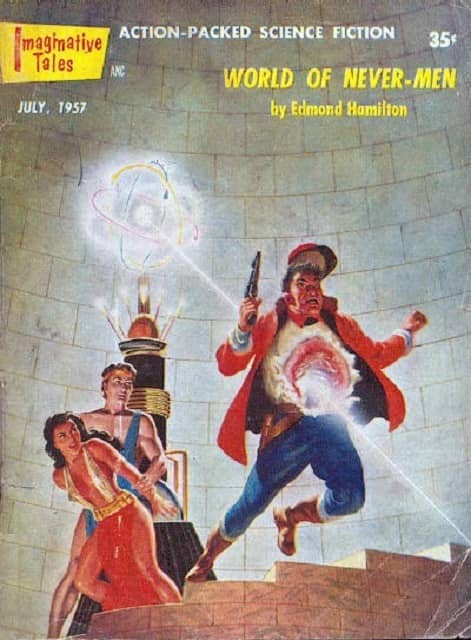

Imaginative Tales, July 1957: A Retro-Review

|

|

Imaginative Tales was the adventure oriented companion magazine to William Hamling’s Imagination. Imagination (often called Madge) is still affectionately remembered by some older fans — it was a fun magazine, though I can’t say it published much really memorable fiction. Imaginative Tales arguably tried to be even funner, but I think less successfully, based on my limited exposure.

(Hamling, by the way, is a controversial figure, not really remembered, I gather, as affectionately as his magazine. He lived to be 95, dying in 2016. He is reported to have rather gruffly rebuffed any attempts to discuss his SF publishing career over the past few decades of his life. He started Rogue magazine in 1955, as a competitor to Playboy, and much of his latter-day publishing efforts were in the “adult” genre.)

The cover is by Malcolm Smith. The interiors are uncredited, though I recognize a signature for “Becker,” and the ISFDB suggests W. E. Terry for another. The interiors are 2 color, by the way.

This issue features a novella, “World of Never-Men,” by Edmond Hamilton, and five short stories. One is by Robert Moore Williams, “The Red Rash Deaths,” and the other four are by some combination of Randall Garrett and Robert Silverberg, who, as I recall, were working together at the time, producing reams of fiction for the likes of Hamling.

They often collaborated, and they shared pseudonyms. These stories are “Devil’s World,” by Garrett alone, “Hot Trip for Venus,” listed on the TOC as by “Ralph Burke,” bylined Garrett above the story’s text, and possibly by both Silverberg and Garrett, though Silverberg doesn’t remember — perhaps it was Garrett alone; “Pirates of the Void,” as by “Ivar Jorgensen,” in this case, says Silverberg, was written by Garrett alone (the “Jorgensen” pseudonym was actually Paul Fairman’s, but Hamling thought it was a house name, and to Fairman’s distress, he used to slap it on stories by the likes of Silverberg); and finally “The Assassin,” by Silverberg alone.

I’ll cover the short stories first. They’re mostly fairly weak, though I did like “The Assassin.” This is about a man who invents a time machine in order to stop John Wilkes Booth from killing Lincoln. The way his effort (inevitably) fails is very logical.

The other stories are all pretty formulaic adventure, and each is at least a twist short of real interest. “Pirates of the Void” is the best, I suppose, about a sort of maintenance tech on an artificial satellite who happens to be there when pirates arrive. He has to hide, then find a way (unarmed) to subdue the criminals. I thought he had it a bit too easy…

“Hot Trip for Venus” probably has a more interesting setup, as a space pilot discovers that the spaceship line’s owner and son are running drugs to the primitive inhabitants of Venus. He plans to return to Venus and find proof — but his pilot license is pulled, so he implausibly impersonates another pilot… and then on Venus it’s just a short jaunt into the woods and he runs across the bad guy. Again… just too easy.

Likewise “Devil’s World,” where a man sent to investigate suspected crime on Mercury is caught and forced to work on the sunside. Again, his eventual turning of the tables was just too easy. And, in all of these stories — not that it matters, really — the scientific notions are just silly.

As for Robert Moore Williams’ “The Red Rash Deaths,” it’s about a policeman investigating a mysterious plague — a terribly contagious red rash has caused dozens of hundreds of deaths. He tracks down a strange man who seems associated with the deaths… and a deus ex machina (or ex futura) solves his predicament.

All that said, Edmond Hamilton’s lead novella is actually pretty good. (It has never been reprinted, by the way.) It’s set on Mars, and Colin Barker is an Earthman who is close to the Martian natives (who seem fully human, really — perhaps both Earthmen and Martians are descended from a common stock in this universe). He encounters an old Martian friend who tells him of a terrible secret — he has just returned from across the “Bitter Sea,” and he encountered evidence of the long rumored not men — androids. But almost immediately Barker is knocked out, and his friend killed, with Barker framed for the murder. He escapes just in time, and decides he has to cross the Bitter Sea and find the android city, Chelorne. He falls in with a crew of bandits, who believe he can lead them to Chelorne. He also meets an alluring Martian woman. And so they journey towards Chelorne… and there they find the secret — which actually is fairly interesting. I won’t spoil it any further.

|

|

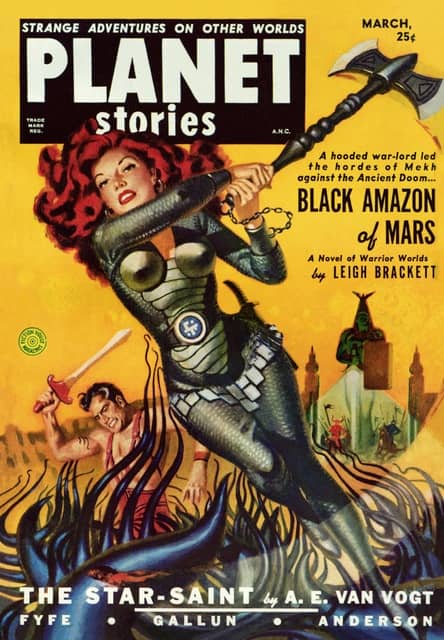

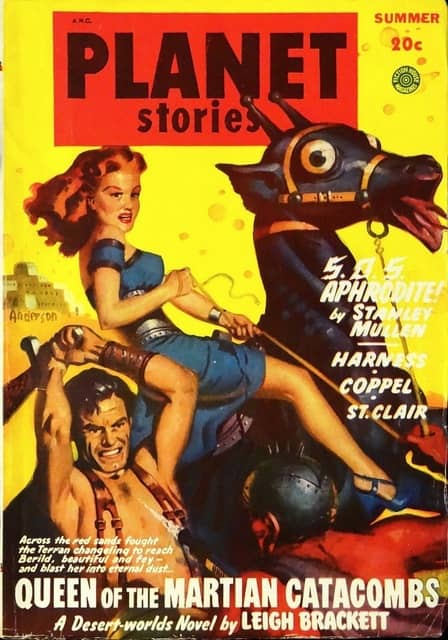

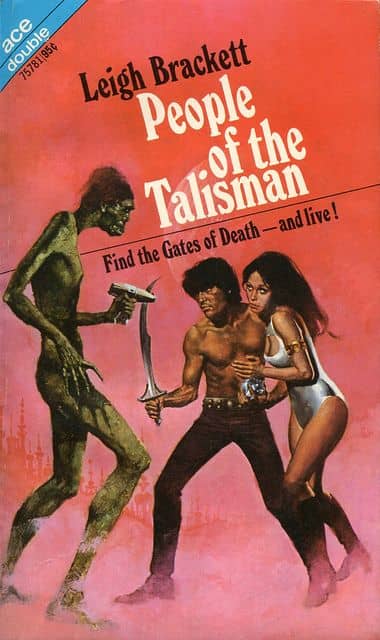

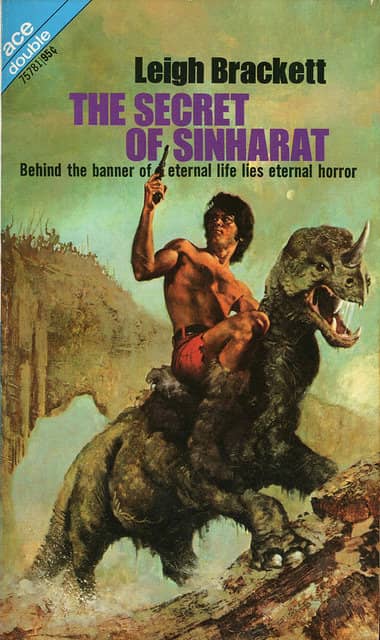

I actually quite enjoyed the story. And I was struck — it’s hard to miss — by the similarity of Hamilton’s Mars depicted here to his wife Leigh Brackett’s Mars. (We might note that it is widely believed that Hamilton did the revisions and expansions to Brackett’s “Black Amazon of Mars” and “Queen of the Martian Catacombs” for the Ace Double publication as People of the Talisman/The Secret of Sinharat.) One could even wonder if Brackett had a hand in this story, though it mostly seems more like Hamilton to me. At any rate, if he was borrowing from his wife, it was fruitful borrowing.

|

|

Other features of the magazine include an Editorial (Hamling predicts a manned visit to “Dear Old Venus” by the end of the 20th Century), a few short science-snippets (one skeptical of flying saucers, one about math, one about orbits), several cartoons, and a few end of the book departments of fannish interest. One is called Cosmic Pen Club, and consists of introductions and addresses from fans looking to correspond with other fans. The names (none of them familiar to me) are Victor Gustine, Laurie Schoenbaum, Carroll Shaffer, Thomas Hritz, Harry Fish, James Wanger, Joie Drake (who calls herself a “grass widow”), Peter Kane, Jr., Nicholas de Morgan, Fred Church, Alberta Leek, Thomas Wade, Vincent Roach, Robert L. Brown, Bonnie Dimitry, Michael Dunn, Daniel Pittinsky, Duane Foster, Robert Martin, Roger Dard (from Australia), Jack Sayers, Jeannette Nagle, Knight Cashwell, Bruce Maguire, and Denny Hill. If anyone recognizes any fans from these names, that would be cool. (Roger Dard, at least, was a fairly prominent Australian fan.)

There was also a column on upcoming SF films, called Scientifilm Marquee, and a letter column. The letter writers were Malcolm Smith (the artist, rebutting the complaints of inaccuracy made in a previous lettercol), David Westfall, Karen Hayden, Edward Jazdzewski, Mrs. Audie Meyer, Kirby McCauley, and Manuel Guerra. The only name I know is Kirby McCauley, who was 16 at the time, but who became a major literary agent (representing for example Stephen King, Roger Zelazny, and George R. R. Martin), as well as anthologist, and the chair of the first World Fantasy Convention. McCauley died in 2014.

Rich Horton’s last Retro Review for us was a look at the May and July, 1954 issues of Beyond Fantasy Fiction. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. See all of Rich’s articles here.

Love those Ace Double covers – whoever the artist was, he apparently thought Eric John Stark looked just like Jim Morrison.

The artist was someone named Enrich. Indeed, Stark does look a bit like Morrison! The Stark depicted by Steranko on the original covers of the Skaith books is rather more like it.

That’s the second Ace Double edition pairing these books, by the way, from 1971. There was an earlier edition, from 1964, with covers by Ed Emshwiller.

But surely the original PLANET STORIES covers are the best! (By Allen Anderson.)

It makes you wish that Hollywood – especially “old” Hollywood knew what to do with these stories. What I wouldn’t give to see Clint Eastwood as Stark…

Great review (as always). The Planet covers (and the Planet texts) of Brackett’s stories are indeed the best. I’ll have to look up this EH novella, though: I have a soft spot for his work, and I think he’s one of the few sf writers of the pre-Campbell era whose writing improves over the decades.

It’s not a beautiful image, but that cover for IT is certainly memorable. It reminds me of some of the gorier descriptions of blaster fire in Asimov’s early work. It wasn’t like phaser-fire on Star Trek where phasers discreetly and mysteriously disintegrate the entire body (and nothing else).