Something Sinister in Savertown: Erica Satifka’s Stay Crazy

|

|

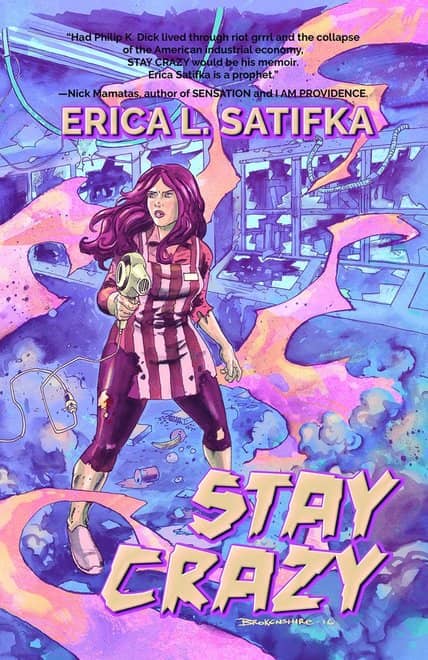

If you missed Erica Satifka’s Stay Crazy, her debut psychological thriller from a couple year back, not to worry. There’s a lot going on, all the time, and it happens to the best of us. But the fact that it won the British Fantasy Award for best newcomer is perhaps reason enough bring it to your attention. Satifka has crafted a tale of mental illness and weirdness set against the deeper malignancy of a post-industrial Midwest and despair, tied up nicely by some frustratingly relatable inter-dimensional entities.

There’s a long tradition in fiction and myth that those who are not entirely sane nonetheless have perceptions, resources, and even abilities beyond those of ordinary folk. Insanity is sometimes the price of vision. Characters of Philip K. Dick for instance, who’s work Satifka’s has been compared with, immediately spring to mind. There are similarly lots of authors who play with the idea of the unreliable narrator, something that Gene Wolfe does to great effect. How is the narrative itself subverted when the reader can’t trust the person telling the story, or the person telling the story can’t trust their own perceptions?

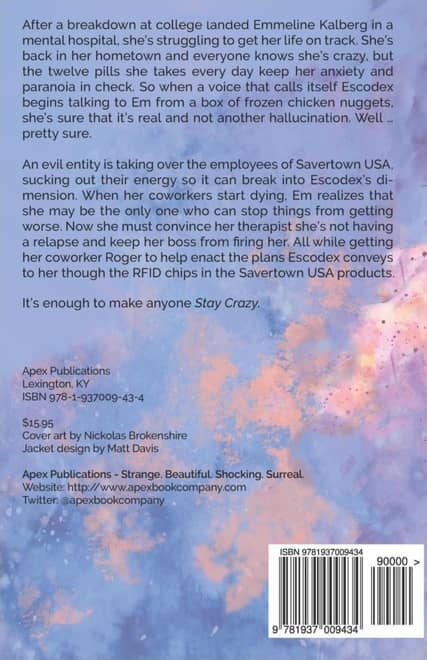

Satifka’s Stay Crazy plays into both these questions by building the narrative around Emma, an erstwhile college student whose schizophrenia has cost her the chance to escape a dying Midwestern town (on economic life-support by a giant Walmart-esque superstore called Savertown, USA). The reader joins Emma, who comes to herself in a mental hospital after a psychotic break, returning home, reconciling herself to her condition and trying to put her life back together with her mother and a Fundamentalist Christian younger sister.

Em inevitably gets a job at Savertown USA, the only place in town to find work, and despite her continual and biting sarcasm for the ridiculous team meetings, decorations, and moral-boosting she finds a sort of peace being a cog in a larger machine with a repetitive, mindless task to perform as a stocker in the frozen-food section. She begins to form relationships: a friendship with her supervisor, a romance with another patient she meets on one of her visits to her unremittingly-loathed psychiatrist. (Her relationship with her sister and mom, however, seem uneven. The way these two supporting characters are portrayed feels jerky, as though their strings are being pulled a little too sharply in different directions — veering abruptly from indifference to love as the story requires.)

As Em’s relationships develop and she begins to put her life into a new order, Satifka expertly illustrates how tenuous this grip on reality can become for someone dealing with schizophrenia as strange events begin to occur and the reader, like Em, has difficulty sorting out what is real. Satifka also shows how this devastates relationships: throughout the novel we see Em making steps to connect with her coworkers, peers, and family only to have these dissolve at critical junctures through relapses of Em’s psychotic tendencies.

But the backstory, of course, is that something sinister is taking place at Savertown, USA. A multidimensional entity is draining the life force of the employees, driving them one by one to commit suicide as it siphons off their vital energy, collecting it and growing in strength so that it can push into our own plane. Em’s already-scrambled brain makes her immune it its effects, and another multidimensional entity — this one called Escodex — contacts her to try to stop it. Escodex is a kind of policeman or middling bureaucrat. He can’t interact physically with our plane but can communicate instructions to Em through RFID chips in merchandise when she holds them up to her head. They form an uneasy alliance in which Escodex uses Em to first gather surveillance on the spread of the malignant entity’s effects and ultimately to stop it and save the world.

The problem is that all of this fits the mold of a psychotic delusion, and as Em stops taking her medications and her perceptions of the world become increasingly disjointed, the reader is left with the suspicion that the entire thing is a figment of Em’s increasingly tenuous grasp on reality. Ironically though, as Em’s relapse intensifies, Escodex becomes what grounds her in reality, a voice in her head urging her to take her medicine to keep her mind clear for the mission. Escodex also becomes Em’s bridge to her first real ally, a co-worker who has been dealing with mental health issues for years and provides a voice of encouragement to Em that things don’t necessarily get better but can be endured.

Yet Escodex, as real as he apparently is, is still using Em. This is a theme through the book: people being used by powers (malevolent or otherwise) they don’t understand and can do little to resist. Em’s brain itself is an example of one of these powers, hijacking her view of reality and consistently sabotaging her chances of getting close to people. The entity at Savertown, USA, is another, but Satifka’s imaginary superstore is clearly a stand-in for a deeper kind of control, that of corporate America offering citizens of Em’s town the only opportunity of employment but at the same time draining them of meaning and ultimately volition:

“You don’t have to go back there,” Em said lamely. Of course, though, the cashier did. What could Em possibly do to dissuade her from walking away from her only source of income? Nothing. There was nothing else in Clear Falls for this woman, nothing for any of them. And in only a few years’ time, Em would be subject to the same fate if she stayed here, forced to work in a minimum wage job managed by jerks. Even if there were no space aliens or intergalactic sleuths in the picture, the economic picture of Clear Falls, Pennsylvania was a dystopia.

Even if Roger and I save it all, Em thought, we’re still f—ed. (pp. 196-7)

And even though Escodex provides the thread of reality throughout, it seems all too likely he may turn out to be middle-management as well, just using Em to get the job done, ending their connection with a “thank you for your service” as flat and meaningless as any pink slip.

Without giving too much away, the ending of the novel is especially poignant because it shows that things might not ever really change for Em. She’ll be attempting to manage her schizophrenia for the rest of her life. But it’s a realization edged with a thin line of hope as she realizes that brokenness doesn’t necessarily mean emptiness and that there are worse things than staying crazy.

Stephen Case has published fiction at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, and Daily Science Fiction. His reviews have appeared at Fiction Vortex and Strange Horizons, as well as his own blog, stephenreidcase.com. His last article for us was a paired review of Peter S. Beagle’s The Overneath and Jane Yolen’s The Emerald Circus.

“A psychotic is just a guy who’s found out what’s going on.” William S. Burroughs