Sorcery and Science: The Broken Lands by Fred Saberhagen

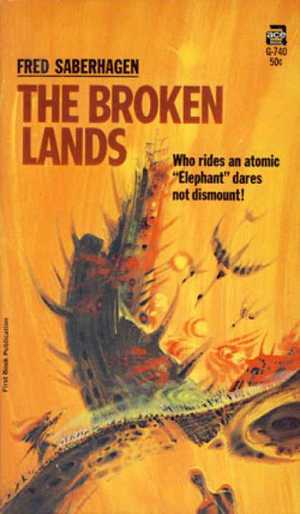

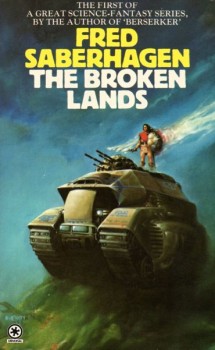

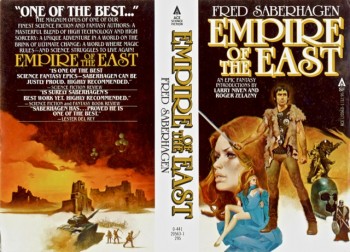

I wonder if Fred Saberhagen suspected that his short 1968 novel, The Broken Lands, was laying the groundwork for a series that would ultimately run 15 volumes. The initial three books, The Broken Lands, The Black Mountains (1971), and Changeling Earth (1973) — collected together as The Empire of the East — take place in America a long time after some yet-undefined catastrophe. While bits and pieces of technology — one giant piece in particular — survive, there is also magic. Wizards, familiars, demons, elementals, even love charms, they’re all there in a very unfamiliar landscape.

I wonder if Fred Saberhagen suspected that his short 1968 novel, The Broken Lands, was laying the groundwork for a series that would ultimately run 15 volumes. The initial three books, The Broken Lands, The Black Mountains (1971), and Changeling Earth (1973) — collected together as The Empire of the East — take place in America a long time after some yet-undefined catastrophe. While bits and pieces of technology — one giant piece in particular — survive, there is also magic. Wizards, familiars, demons, elementals, even love charms, they’re all there in a very unfamiliar landscape.

The setup for The Broken Lands is one only the slackest of readers haven’t encountered a hundred times or more: young boy faces off against evil empire, discovering and drawing on heretofore unknown skills and abilities. Along the way he encounters unrequited love, a wise mentor, and a villain with honor (and more style than everyone else). The primary narrative concerns the search for a secret thing with which to fight the empire. Did I mention the empire was evil?

I like this book way more than I should. Stock as the characters are, routine as the setup feels, at some point we start getting hints that something bigger and better is going on. In fact, that it feels like what’s coming next is going to be familiar, and then it isn’t, is a big part of the book’s success for me. In the meantime Saberhagen’s writing is clean and the story’s pacing is brisk. There’s little poetry in The Broken Lands, but there is an economy that keeps the undertakings lively and enjoyable.

Only recently has the much-feared Empire of the East expanded its grasping hands into the West. The people of the region, mostly farmers, have been easily conquered and cowed into submission. In addition to bronze-helmeted soldiers, the forces under the local Satrap, Ekuman, include intelligent flying reptiles and a pair of wizards. It is with his wizards the Satrap is conferring as the book begins.

A resistance to imperial rule has formed and is led by an alliance calling itself the Free Folk. One of its wizards has fallen into the Satrap’s hands and he demands that every bit of knowledge that can be extracted from him be done at once. It isn’t easy though, and in the conflict of wills between prisoner and captors, the wizard dies. Before he does, though, he makes a pronouncement on the Satrap’s future:

A resistance to imperial rule has formed and is led by an alliance calling itself the Free Folk. One of its wizards has fallen into the Satrap’s hands and he demands that every bit of knowledge that can be extracted from him be done at once. It isn’t easy though, and in the conflict of wills between prisoner and captors, the wizard dies. Before he does, though, he makes a pronouncement on the Satrap’s future:

“Hear me, for I am Ardneh! Ardneh, who rides the Elephant, who wields the lightning, who rends fortifications as the rushing passage of time consumes cheap cloth. You slay me in this avatar, but I live on in other human beings. I am Ardneh, and in the end I will slay thee, and thou wilt not live on.”

Given the circumstances, Ekuman knew no alarm at being threatened. The word “Elephant,” though, caught his attention sharply. He glanced quickly at his wizards when it was uttered. Zarf’s and Elslood’s eyes fell before his, and he returned his full attention to the prisoner.

Pain showed now in the prisoner’s face, and sounded in his voice. Defenses crumbling, powers failing, he was quickly becoming no more than an old man, no more than another victim about to die. He labored on, with croaking speech.

“Hear me, Ekuman. Neither by day nor by night will I slay thee. Neither with the blade nor with the bow. Neither with the edge of the hand…nor with the fist. Neither with the wet…nor with the dry…”

More than anything, it is the word “elephant” that piques Ekuman’s interest. Symbols of the ancient, almost mythical creature have become the resistance’s emblem. He is convinced that it refers to some real item of power hidden away in his new realm. His own court wizards have warned him that without the Elephant’s power, “his rule was doomed to perish.”

More than anything, it is the word “elephant” that piques Ekuman’s interest. Symbols of the ancient, almost mythical creature have become the resistance’s emblem. He is convinced that it refers to some real item of power hidden away in his new realm. His own court wizards have warned him that without the Elephant’s power, “his rule was doomed to perish.”

The primary protagonist of The Broken Lands is introduced in the second chapter. Rolf is a sixteen year old farm boy whose parents are killed by the Satrap’s forces and whose sister is taken, presumably into slavery. Later, when he and a trader he is traveling with are stopped by soldiers for questioning, he almost unintentionally tries to kill one of them. In the skirmish the trader, Mewick, reveals himself to be a master fighter and kills all three. Mewick is a spy for the Free Folk and has been scouting the land for any possible allies against the Empire.

Enlisted into the resistance, Rolf volunteers to be part of an expedition to recover the Elephant. One of the giant owls allied to the Free Folk found a cave in the hills near the Satrap’s fortress. Signs indicate that the Elephant, whatever it is, must lie inside. Along with Thomas, the best of the Free Folks’ commanders, the two men and two owls approach the cave by stealth.

What is the Elephant? Rolf doesn’t know, but anyone who has seen most of the covers for the book should be able to figure it out. If not, this is what Rolf finds:

With slow steps Rolf walked twice around the Elephant, keeping a cautious distance from it, holding his torch high.

Except for the impression that it gave of enormous and mysterious power, this before him did not much resemble the creature depicted in the symbols. This was a flattened metal lozenge of smooth regular curves, built low to the ground for something of its massive size. Here could be seen no fantastically flexible snout, no jutting teeth. There was no real face at all, only some thin hollowed metal shafts projecting all in one direction from the topmost hump. Looking closely Rolf could see that around that hump, or head, were set some tiny glassy-looking things, like the false eyes of some monstrous statue.

Elephant was legless, which only made it all the more impressive by raising the question of how its obvious power was to be unfolded and applied. Neither were there any proper wheels, such as a cart or wagon had. Instead Elephant rested on two endless belts of heavy, studded metal plates, whose shielded upper course ran higher than Rolf’s head.

On the dull metal of each flank, painted small in size but with Old World precision, was the familiar sign — the animal shape, gray and powerful, some trick of the painter’s art telling the viewer that what it represented was gigantic. In its monstrous gripping nose the creature in the painting brandished a sharp-pointed spear, jagged all along its length. Under its feet it trod the symbols:

426th ARMORED DIVISION

-whose meaning, and even language, were strange to Rolf. Now, holding his breath, he ventured to put out a hand and touch a part of one of the endless belts, a plate of armor too heavy for a man to carry or for a riding-beast to wear into a fight. Nothing seemed to happen from the touch. Rolf dared to lay his hand flat on the featureless surface of the Elephant’s metal flank.

Without securing the Elephant, Rolf is captured and Thomas is forced to go on the run. The Satrap discovers the location of the Elephant and sends his soldiers and slaves to find a way to get it out of the mountain cave. Meanwhile, his daughter, Charmian, is plotting against him, and her betrothed, the satrap Chup, seems to have secret plans of his own. Armies are on the move and a lightning-unleashing talisman is discovered and its powers let loose. And in the end, the Elephant is set free, its strength and weight brought to bear on those who stand in its way.

Without securing the Elephant, Rolf is captured and Thomas is forced to go on the run. The Satrap discovers the location of the Elephant and sends his soldiers and slaves to find a way to get it out of the mountain cave. Meanwhile, his daughter, Charmian, is plotting against him, and her betrothed, the satrap Chup, seems to have secret plans of his own. Armies are on the move and a lightning-unleashing talisman is discovered and its powers let loose. And in the end, the Elephant is set free, its strength and weight brought to bear on those who stand in its way.

I — I think I have made known lately — am a fan of books that don’t hew to the established sci-fi and fantasy party lines. With tanks and demons on hand, Saberhagen was definitely mixing things up. He’s also jettisoned most of the Romantic or faux-archaic trappings that would soon become de rigueur for most genre fantasy. While in no sense grimdark, there’s a greater feeling of realism than in many fantasy novels tarted up with “forsooths” and what have you. There’s the occasional slip, but most characters speak in standard, modern English. Until Glen Cook’s Black Company books, I’m not sure I can think of any other author in fantasy who did that. I imagine it was a little shocking in 1968.

Now it’s passé and it’s been done to death. Today, too many writers seem intent on stripping the fantastic and magical from fantasy. I don’t think that’s what Saberhagen was doing. I think, perhaps because he’d been an electronics tech, perhaps because he mostly wrote sci-fi, he was simply trying to craft a more naturalistic story — with demons. In fact, I almost think Saberhagen deliberately chose to use some of the hoariest fantasy tropes exactly to examine them in the light of this then-novel style. After reading only the first book, I have to withhold judgment as to how successful he is at doing anything really new with these old bits and pieces, but so far, I will say I’m ready and willing to follow along until the end.

I’m looking forward to the next two books in the series. (There’s a fourth book, Ardneh’s Sword (2006), set long after the initial books). As I mentioned, toward the end of The Broken Lands, a sense that something big, something way beyond anything the reader’s seen yet, is lurking just off stage and readying itself for an appearance. We still don’t know who Ardneh is or what brought about magic in the good old US of A. So come on back next week, and you can read what I have to say about The Black Mountains.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now.

I read the Empire of the East several years ago and I know just what you mean about liking it more than you should. The basic idea is pretty cheesy; it’s like a slightly more sophisticated version of something you would see in a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. But it was undeniable fun, and and as the series progresses, Saberhagen does some unexpected things with his plot and – especially – his characters. It’s not any kind of masterpiece, but it’s a very enjoyable ride.

I never actually read Empire of the East, but I did read a pile of the Swords and Lost Swords books many years ago. Someday …

@Thomas P. – I pretty much know what’s going on in the next two books and, still, I’m really jazzed to see exactly what he does.

@Joe H – I definitely want to read the first couple of Swords books. Several friends almost swore by them back they came out.

Today, too many writers seem intent on stripping the fantastic and magical from fantasy.”

Agreed. I think that’s leftover from the jaded late 20th Century scientific view that we were on the verge of “understanding” everything and everything was materialistic, meaningless, and ultimately boring and horrible. I actually think Quantum physics and the new science (where many believe there is not only the unknown for humans but also the unknowable) actually helped bring magic and a sense of wonder back. But many people (and writers) are still stuck in the old 20th Century paradigm. Cultural change takes time.

I had been intrigued by Empire of the East when it came out. I’m not sure the books would be my cup of tea, but I may check them out some day (a sophisticated Hannah-Barbera story doesn’t sound bad!). It does seem that Saberhagen was breaking some new ground at the time. Thanks for the thoughtful review, Fletcher!