Roleplaying the Possibility Wars: Torg Eternity (Part One)

Later today, early tomorrow, sometime next week, the world began to end.

Later today, early tomorrow, sometime next week, the world began to end.

Imagine the Earth wreathed in storms spitting red and blue lightning. Imagine invaders from beyond reality turning the world piece by piece into something other than what we know. Imagine a cyberpunk theocracy in France, dinosaurs overruning the great cities of the United States, colonial gothic horrors in India, a post-apocalyptic wasteland in Russia haunted by decadent technodemons, zombies in East Asia, a mad pulp super-villain and would-be Pharaoh building a fascist empire among the pyramids of Egypt, and elves and wizards and dungeons and dragons in the British Isles and Scandinavia.

The storm has a name …

Torg is a tabletop role-playing game first published in 1990 by West End Games. I started running a campaign in 1991 that lasted for over a decade, off and on. Last year game publisher Ulisses Spiele launched a successful kickstarter to fund an updated edition of the game, Torg Eternity; they’re currently running another kickstarter for the rebooted game’s first sourcebook, The Living Land. The original Torg was the most explosively imaginative game I’ve ever played. The new is an intelligent update, refining the first version’s rules and concepts while respecting what made it work. Preparing to run the first session of a Torg Eternity campaign, I was shocked to realise how much power the original game had for me; and how well the new game not only maintained that imaginative power but added to it.

In what does that power dwell? I’ll discuss that question with respect to actual game play in part two of this review, but much of it has to do with the basic concepts of the old and new Torg. Worth noting that I leaped at the chance to review Torg Eternity despite not having run any RPG in at least six years: the idea of a rebooted Torg pulled me back to a pastime from which I’d drifted away. And then reading the Torg Eternity message boards was deeply stirring. Seeing active discussion of the game’s characters and concepts was like having a part of me brought back to life. More than a dozen years after I’d last run a Torg session the game had kept its hold on my imagination — under the surface, but always present.

In what does that power dwell? I’ll discuss that question with respect to actual game play in part two of this review, but much of it has to do with the basic concepts of the old and new Torg. Worth noting that I leaped at the chance to review Torg Eternity despite not having run any RPG in at least six years: the idea of a rebooted Torg pulled me back to a pastime from which I’d drifted away. And then reading the Torg Eternity message boards was deeply stirring. Seeing active discussion of the game’s characters and concepts was like having a part of me brought back to life. More than a dozen years after I’d last run a Torg session the game had kept its hold on my imagination — under the surface, but always present.

Both old and new Torg are thematically rich. They’re about things in the way not a lot of games necessarily are. Of course action’s core to Torg, action which evokes the flowing excitement of a good genre film. But there’s more to it, potentially at least. There’s a richness to the setting that encourages fascinating role-playing, as characters of different worlds meet and work together. And there is that density of imagination: you’re given seven different worlds (eight, with the invaded Earth included) each with its own villains, heroes, conspiracies, wonders, and monsters. You can cast spells, invoke miracles, use psionics — all these things done a little differently in each world. The game’s genre-savvy, with each world speaking to the nature of the genre it embodies; and also each with a specificity, a twist, so that each world says something new about its genre and the stories set within it.

But if it is a game about many things, for me what makes Torg special is that at its core it’s a game about stories. Every tabletop role-playing game is, of course, one way or another. Every RPG’s a collaborative game of storymaking. Every session sees the group at the table incarnate the narrative arc. Torg makes that subtext a part of its text, as characters fight back against the invading stories overwhelming the world by telling their own stories to spark people with the energy of possibility. By becoming heroes about whose great deeds stories are told, and then by telling those stories, the players reshape reality against forces that would dictate reality for themselves. That core concept’s stuck with me for years.

(And yet note that if this subtextual depth is very real and implicitly present in every Torg game, it’s also not something that you have to worry about. Sometimes you just want to see a cybernetically-enhanced elf ride a dinosaur into battle against ninja werewolves toting weird-science electro-rays. The game covers a lot of ground.)

(And yet note that if this subtextual depth is very real and implicitly present in every Torg game, it’s also not something that you have to worry about. Sometimes you just want to see a cybernetically-enhanced elf ride a dinosaur into battle against ninja werewolves toting weird-science electro-rays. The game covers a lot of ground.)

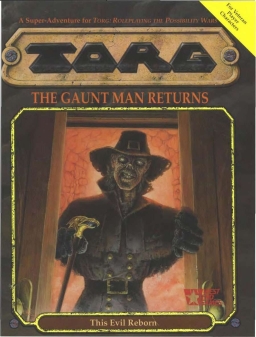

The core myth of the game is that there’s an infinite number of worlds, some Earthlike and some not, born out of a conflict of primal entities of creation and entropy. The force of entropy has raised powerful evil creatures in various worlds, or cosms, to become High Lords: interdimensional conquerors who seek to drain other worlds of their creative possibility energy. Legend says if one High Lord gains enough possibility energy, they will become the godlike being called the Torg. Long ago the most feared of these possibility raiders, the Gaunt Man, found a dimension filled with more possibility energy than any other, so much energy the High Lord that captured it would surely become Torg. But this dimension, Core Earth, held so much energy that any one High Lord who invaded it would be destroyed by the backlash. Possibility energy is a powerful thing, you see. Repercussions of the clash of realities, the loosing of possibilities, include terrible reality storms that can unmake the world in a flicker of red and blue lightning. In the wake of these storms the possibility energy raises up heroes — who are therefore known as Storm Knights.

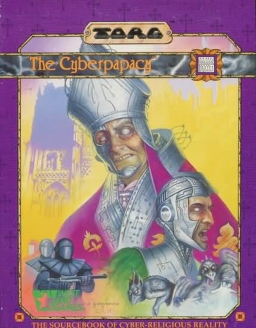

The Gaunt Man knows Core Earth will create an unprecedented number of Storm Knights but, nothing daunted, has recruited allies to invade the world he cannot defeat alone. These are other High Lords, some former lieutenants, some partners of convenience. All of them aspire to become Torg, all plan to betray each other, and all plot against each other as they divide up the Earth and begin the conflict called the Possibility Wars. The Gaunt Man, who rules the realm of gothic horror called Orrorsh, is the most terrible of the High Lords, but all are powerful foes. There are six others: Angar Uthorion, servant of the Gaunt Man and dark lord of the high-fantasy realm of Aysle; Cyberpope Jean Malraux, who controls the cyberpunk dystopia called the Cyberpapacy; Baruk Kaah, the lizard-man barbarian ruler of the Living Land, a realm of jungles and mists and hidden wonders given great spiritual power by the omnipresent goddess Lanala; Doctor Mobius, the mad pulp villain whose shocktroopers and masked marauders have returned Egypt to a high-adventure 1930s filled with hard-boiled PIs, gadgeteers boasting weird-science wonders, and cloaked mystery men; Kranod, the cybernetically-ehanced demon who struggles to keep control of the techno-horror realm of Tharkold, where a radioactive wasteland hides lost pieces of technology and mutated abominations as well as splatterpunk terrors; and the unknown leader of the high-tech espionage-filled realm called Pan-Pacifica, where zombie outbreaks are met by the repressive security forces of the Kanawa megacorporation in a reality filled with martial-arts action and bloody revenge-fuelled gunplay.

(I will note here a bit of cleverness I always loved: Angar Uthorion, the high-fantasy dark lord, is the servant of the Gaunt Man — exactly as the prototype of all high-fantasy dark lords, Tolkien’s Sauron, was the servant of Morgoth god of evil. This sort of grace note is one of the secondary pleasures of the game.)

(I will note here a bit of cleverness I always loved: Angar Uthorion, the high-fantasy dark lord, is the servant of the Gaunt Man — exactly as the prototype of all high-fantasy dark lords, Tolkien’s Sauron, was the servant of Morgoth god of evil. This sort of grace note is one of the secondary pleasures of the game.)

The players take the role of heroes charged with possibility energy, resisting the schemes of the High Lords. You can play someone from Core Earth still clinging to their reality, a more-or-less ordinary person caught up in the chaos of the invasion. Or you can play someone from Core Earth who converted to one of the invading realities before taking up arms against the invaders and lives according to the other world’s rules. Or you can play someone from one of the invading realms; many of the High Lords don’t have total control of their home realities. Doctor Mobius is simply one of any number of master villains in his home world, while Angar Uthorion is fought by the armies of the Lady of Light, Pella Ardinay. Others have yet to eliminate all resistance — Jean Malraux can’t crush the covens of witches who secretly fight against him, while Kranod’s demons are locked in an endless war with the remnants of humanity on their world.

There are options, in other words. There are possibilities.

The original Torg was created by Greg Gordon, Bill Slavicsek, and Douglas Kaufman, with Ed Stark,

Greg Farshtey, Stan!, Brian Schomburg, Christopher Kubasik, Ray Winninger, and Paul Murphy (there was a revised version of the rules in 2005 by Jim Ogle, which I think my group helped playtest; it seems long ago now). The writing and design team for Torg Eternity is Shane Lacy Hensley, Darrell Hayhurst, Markus Plötz, Deanna Gilbert, and Ross Watson. Many of the original Torg designers are involved in Torg Eternity to some degree, and indeed Hensley’s first published game-writing credit was a module for the original Torg. Gordon contributes a foreword to the new rulebook recalling the game’s origin, remembering:

… [something] was off when I could get a police escort to the polls to vote in a mayoral election and my friends could not; or when my wife couldn’t get heard at a tech meeting where she worked; or when they lined us up for lunch by religious affiliation when I attended elementary school in Colombia. There were plenty of -isms that would explain that, but how could I generalize these conflicts and blow them up to game size? Ah … the world was the same, but reality was different for each participant, the realities were in conflict, and there was a price to be paid for that. That was the metaphor I was looking for. It wasn’t yet enough for a game; but if the realities governed every aspect of existence, technology, magic, spirituality, even what ideas could be successfully expressed? That. Could. Work.

This wasn’t immediately obvious to me when I played the original Torg a quarter-century ago or more, but that’s the beauty of a powerful metaphor: it doesn’t have to be noticed to add depth to the experience of a story. Gordon had the seed of a game that could depict something crucial about the world — the way that multiple realities co-exist and interact.

Still, what makes a game succeed is more than any central metaphorical conceit, and often more than its central narrative. A game needs a strong system, and Torg had that. It was full of mechanics that were sheer fun to play, and they’re all still here.

Still, what makes a game succeed is more than any central metaphorical conceit, and often more than its central narrative. A game needs a strong system, and Torg had that. It was full of mechanics that were sheer fun to play, and they’re all still here.

In order to be able to deal with a range of values that stretched from “the damage done by a punch” to “the damage done by the main cannon of the Death Star,” Torg used a logarithmic Bonus Chart instead of a straight die roll — instead of rolling a die and adding it to a skill or attribute, you rolled the die, found the number you’d rolled on the chart, and added the result that gave you to your skill or attribute. The key there was that the twenty-sided die exploded on rolls of ten or twenty. Lucky rolls could generate spectacular results, especially once hero points (“possibilities”) were added. And once card play was done.

Because even beyond the excitement of rolling a number above 60 on a 20-sided die, what really made Torg stand out was the Drama Deck, a set of cards that were used to determine initiative and that players could use to get bonuses to their actions. Players could also use certain cards to activate subplots, partially taking control of the narrative, shaping the story along with the gamemaster. Torg was perhaps the first tabletop role-playing game to incorporate cards, and they were so wonderfully fun players in my Torg game quickly adapted them to other systems they were running, from Marvel Super-Heroes to Star Wars. The bonus chart and exploding dice and cards are all back in Torg Eternity — with a second exploding die for damage, and new decks of cards to make the play smoother.

Also still present is the game’s sense of story construction. Torg cleverly encourages structured sessions without setting up plot railroads. Gamemasters are asked to think in terms of scenes, which each scene either “standard” or “dramatic,” and a collection of scenes building an Act. Experience (in the new game) is awarded at the end of an Act, while hero points and certain abilities reset after each scene. The dramatic scenes have slightly different mechanical effects, making it tougher for the players, and this in turn works along with the mechanics of card play to create situations where player characters begin a fight or conflict at a disadvantage, struggle to wear down their opponent, and finally win through. The game’s like an introduction to screenwriting, encouraging the gamemaster to think in terms of the structure of a scene. A player of mine once said he found himself breaking down the plot beats in action movies according to Torg rules, working out when the dramatic action started and what cards were played when.

The only real problem I had with the game was there was so much of it. There were wonderful themes, mechanics, and structures to Torg, and a profusion of plot threads, characters, and concepts. Many of them were perceptive, clever, and creative. The problem was that were was almost too much to keep track of. Both in terms of subplots and, especially, in terms of rule subsystems, the game proliferated beyond all control. There were rule systems for constructing spells, for Egyptian engineering, for running the conflicts of megacorporations. Most of them worked well, but the sheer number of them was difficult to cope with. It made things difficult for character construction, too.

The only real problem I had with the game was there was so much of it. There were wonderful themes, mechanics, and structures to Torg, and a profusion of plot threads, characters, and concepts. Many of them were perceptive, clever, and creative. The problem was that were was almost too much to keep track of. Both in terms of subplots and, especially, in terms of rule subsystems, the game proliferated beyond all control. There were rule systems for constructing spells, for Egyptian engineering, for running the conflicts of megacorporations. Most of them worked well, but the sheer number of them was difficult to cope with. It made things difficult for character construction, too.

For example, when the sourcebook describing the realm of gothic horror called Orrorsh came out, it had a ruleset under which the monsters of the realm each had a True Death — a specific way in which each monster had to be killed. Kill them a different way, wander through the realm blasting everything in sight, and they’d just come back in another form. It was an intelligent idea to de-emphasise combat as the solution to everything, and it fit perfectly with the genre. But there were two problems. One, the sourcebook came out after the game had already been out for over a year, meaning people had been killing monsters for that length of time without looking for their True Deaths. Secondly, the best way for characters to find out the True Death of a given monster was to use the Research skill, a specialised quasi-occult skill representing the careful study of crumbling manuscripts and old records. It was a good idea for a skill in that genre, but was basically useless outside of Orrorsh. Meaning that monster-hunter characters had to invest in a skill that would do nothing for them most of the time. (As I recall, I got around this by giving the characters NPCs who had the skill. There are ways to make imperfect rules work. But you’d rather they weren’t imperfect to start with.)

Even the good rules, though, tended to be overwhelming in total. Each realm got its own sourcebook, of spells and equipment and NPCs and factions, which was really needed to make the realm fully come alive in all its details. That meant six rulebooks for each of the invading realms in the original game, then two more for other realities that came along later, plus another for Core Earth, plus another for a pocket dimension that got pulled into the war — and then there were updates for each year of the war, and modules, and sourcebooks covering particularly important cities, and it went on and on. If the Torg supplements were generally very good individually, it still added up quickly.

Torg Eternity faces a different difficulty: in just one rulebook it has to give players and gamemasters enough information to run adventures in eight different worlds. It succeeds in part by simplifying some of the more baroque of the original rules. The designers have done a good job of working back to the philosophy underlying the rules, then simplifying and harmonising the systems. As in the old game, players distribute points into a set of basic attributes (Charisma, Dexterity, Mind, Spirit, and Strength), then put more points into a list of skills (for example, Dodge is a skill based on Dexterity). But the designers have said that they won’t be adding new skills in future sourcebooks, and they can make that statement because the third stage of character creation is to pick perks — basically, special abilities. Psionic powers, the ability to cast spells, cyberware, all these things are perks.

Torg Eternity faces a different difficulty: in just one rulebook it has to give players and gamemasters enough information to run adventures in eight different worlds. It succeeds in part by simplifying some of the more baroque of the original rules. The designers have done a good job of working back to the philosophy underlying the rules, then simplifying and harmonising the systems. As in the old game, players distribute points into a set of basic attributes (Charisma, Dexterity, Mind, Spirit, and Strength), then put more points into a list of skills (for example, Dodge is a skill based on Dexterity). But the designers have said that they won’t be adding new skills in future sourcebooks, and they can make that statement because the third stage of character creation is to pick perks — basically, special abilities. Psionic powers, the ability to cast spells, cyberware, all these things are perks.

This third stage of character creation is new to Torg Eternity, but actually simplifies things tremendously. Instead of trying to make all the different powers and abilities fit into the skill system, as the old game mostly did, the new one’s more flexible. The magic rules, for example, which I always found a little confusing in the original game, are here explained easily. Individual spell lists give each reality’s magic-users a different feel. I’ve worked with players to create two spellcasters so far, and the Ayslish trickster-bard is distinct already from the Cyberpapal witch.

The game’s very well-supported online as well, with active message boards, links to maps and rules and a wiki and other resources on the publisher’s web site, and videos featuring the designers talking about their plans for the various realms and the game overall (frequently recorded against a background of Robert E Howard books and Michael Moorcock paperbacks). The original Torg was notable for what they called the “Infiniverse,” an attempt to let all the players of the game help shape the course of the overall war by filling out surveys. That helped determine what sourcebooks would get released, and which High Lords were able to acquire more territory. It’s something that’s a natural fit with today’s technology, and I’m looking forward to seeing where it goes.

Worth observing as well that the Torg Eternity rulebook and cards are well-designed products. The perfect-bound book is full-colour on every page, with lots of maps and generally well-chosen illustrations that help show off some aspect of the rules or setting. The cards feature some aspects of the original Torg (in flavour text especially) while using more art and having more options — three decks in this game replace and expand on the original single Drama Deck. I did think the art didn’t always match the settings. While the high-tech realms came across nicely, and the savage reality of the Living Land worked quite well, the designs didn’t convey a strong period sense in Orrorsh and the Nile Empire. The warm lighting felt like an odd choice for the gaslit world of Orrorsh, as well.

Worth observing as well that the Torg Eternity rulebook and cards are well-designed products. The perfect-bound book is full-colour on every page, with lots of maps and generally well-chosen illustrations that help show off some aspect of the rules or setting. The cards feature some aspects of the original Torg (in flavour text especially) while using more art and having more options — three decks in this game replace and expand on the original single Drama Deck. I did think the art didn’t always match the settings. While the high-tech realms came across nicely, and the savage reality of the Living Land worked quite well, the designs didn’t convey a strong period sense in Orrorsh and the Nile Empire. The warm lighting felt like an odd choice for the gaslit world of Orrorsh, as well.

Are there more substantive issues with the game? There are choices which I personally wouldn’t have made, but the reasons for which I generally understand. For example, the game assumes that the players will be agents of the Delphi Council, a worldwide organisation that recruits heroes, Storm Knights, and assigns them missions. The Council’s led by a mysterious figure named Quinn Sebastian, an NPC in the original Torg game, who convinced the US government to back his group and give him an aircraft carrier for his base; he’s also working with the UN. I don’t like anything about this set-up. I don’t like the idea of having the players be the agents of a shadowy agency with ties to the American military (my players don’t like it, either). I don’t like having the players be subordinates to some shadowy structure above them. And I don’t see how the UN affiliation can work when at least one and as many as three permanent members of the Security Council are allied with the invaders. (I’ll also note semi-seriously that I don’t care for the semiotics of the thing. One of the illustrations shows Sebastian, an older white guy in a baseball cap, yelling at the UN; the game also specifies that he’s based on the aircraft carrier named for Ronald Reagan, which doesn’t help.)

There is a logic to the Council. It’s a way to get players into an adventure easily, and to give them a way to move easily around the globe. And, given that this Sebastian seems to be the same Sebastian of the first game showing up to try to stop this invasion, he’s also a source of knowledge about how the mechanics of the invasion works: how the High Lords spread their reality, and how you can reclaim territory. But if I choose not to use the Delphi Council, at least this is all easy enough to work into my own game, whether by creating an equivalent organisation without the connection to the US or just by coming up with a story that brings the player characters together naturally and letting the story dictate what adventures they get into.

There is a logic to the Council. It’s a way to get players into an adventure easily, and to give them a way to move easily around the globe. And, given that this Sebastian seems to be the same Sebastian of the first game showing up to try to stop this invasion, he’s also a source of knowledge about how the mechanics of the invasion works: how the High Lords spread their reality, and how you can reclaim territory. But if I choose not to use the Delphi Council, at least this is all easy enough to work into my own game, whether by creating an equivalent organisation without the connection to the US or just by coming up with a story that brings the player characters together naturally and letting the story dictate what adventures they get into.

More worrying is one of the NPCs in the game, a Nile Empire villain from the original Torg: the insidious Wu Han. He’s a master criminal in the vein of Fu Manchu (the American title of the first Fu Manchu novel was The Insidious Fu Manchu) or the Shadow’s archenemy Shiwan Khan, and while that didn’t register to me as a problem a quarter-century ago, in the meanwhile I’ve read some of the Fu Manchu books and followed the arguments around characters like Marvel Comics’ Mandarin. And I am now not sure what to do now with this character who comes out of a tradition of Yellow Peril racism. If he was going to be used, I’d have liked some discussion of the issues around him.

Beyond that, my main quibbles are with what I would have liked to have seen in the rulebook. The difficulty there, of course, is that anything that might have gone in would have had to bump something else out. I’d have liked to have seen more guidance for gamemasters with regards to design philosophy — how to create perks, or whether magic and miracles and psionics should have different effects. But what should be removed? Is this better handled online, through discussion on the message boards? Perhaps.

Otherwise, my main annoyance is a more general issue with the role-playing industry, one that played a part in my drifting away from gaming. And that is the tendency to treat a game as an unfolding story with plot points kept secret from the gamemaster, revealing a metaplot gradually across the course of multiple sourcebooks. I don’t understand the logic of this. As a gamemaster, I want to tell a story with my players, and to do that I feel I need to know basically what’s going on in the game world and what is driving the main non-player characters. It is of course true that I can change anything I don’t like — but I need to know what a plot point is before I know if I want to change it or not. Why is Doctor Mobius expanding his territory southwards across Africa? I don’t know. Is it important? Well, maybe, maybe not.

Otherwise, my main annoyance is a more general issue with the role-playing industry, one that played a part in my drifting away from gaming. And that is the tendency to treat a game as an unfolding story with plot points kept secret from the gamemaster, revealing a metaplot gradually across the course of multiple sourcebooks. I don’t understand the logic of this. As a gamemaster, I want to tell a story with my players, and to do that I feel I need to know basically what’s going on in the game world and what is driving the main non-player characters. It is of course true that I can change anything I don’t like — but I need to know what a plot point is before I know if I want to change it or not. Why is Doctor Mobius expanding his territory southwards across Africa? I don’t know. Is it important? Well, maybe, maybe not.

This was present in the original Torg to some extent, and there as here there’s a good justification: because the metaplot’s going to be shaped by the choices made by players around the world, the game shouldn’t be and can’t be overly prescriptive. I’m arguing, I suppose, that the balance is a little off for me, and I’d like to know more about plans the designers have that seem to be relatively firm.

Beyond that? I might wish the approach to the theme of storytelling had been handled a bit differently. In the original game it was necessary for the characters to tell the story of a glorious deed before they could regain territory without destroying people caught in that territory, and that’s not really the case here. Again, that was a ruleset that was less than satisfactory — you didn’t know if the story had taken root, which meant you didn’t know if you’d be killing large numbers of people when you removed the item anchoring the invading reality to Earth. I didn’t care for that, but I feel as though Torg Eternity might have simplified the rules to the point where the theme gets lost. We’ll see, though, and even if that’s the case, I have some house rules in mind that could make up for it.

It’s certainly worth noting that Torg Eternity evokes cinematic action without relying solely on violence. Combat is assumed to be a major part of the game, but as in the original Torg, it is theoretically possible to defeat the invaders without firing a shot (though practically it’d be so difficult as to be almost unworkable). But how the game conceives of combat goes beyond straight-ahead fighting. Interaction skills — trick, taunt, intimidate, and maneuver — are relatively non-violent options that players are encouraged to use by certain card mechanics. Fights aren’t just blasting away with guns or hacking with swords. They’re broader conflicts, moments of drama and, potentially, glory of many kinds.

I note that certain aspects of good and evil in the different realms have been downplayed and some others heightened. Generally, the gamemaster isn’t asked to determine the moral weight of specific actions, which is I think mostly to the good. At the same time, there’s now a distinction between ‘Storm Knights’ and ‘Stormers.’ Both are able to manipulate possibility energy; they both made moral choices under pressure in the face of an opposing reality, and gained power thereby. But Storm Knights made a choice for self-sacrifice and creativity, while Stormers did the reverse. This is interesting, though underexplored in the rules as they stand; one of the my players might be more of a Stormer than Storm Knight, but I’m unclear if this has any substantive significance.

This is mainly notable because otherwise the mythology and narrative of the game has been updated supremely well. The game’s complex backstory is simplified while the core myth’s retained. The original Torg began with a three-novel series setting up the game, an interesting idea that meant the players who hadn’t read the books would come into a war (and related plot points) already well underway unless their gamemaster simplified things for them. In Torg Eternity the outline of events is retained but is much easier to grasp from the start. Crucially, the idea of a conflict between imagination and entropy is, in the end, the driver of the story. The theme’s present, whether play brings it out or not.

Generally changes to the realities of the game are well-planned, typically in the direction of allowing more stories to be told. The Living Land, the low-technology reality of dinosaurs and lizardfolk, now has lost wonders within it. The original version of the reality was useful for two stories — “escape the Living Land” and “retrieve something or someone left behind in the Living Land” — but now fragments of mysterious other dimensions appearing among the mists open the door to new story shapes. They allow for a new kind of sublimity, perhaps, a new kind of awe, a new way to thrill players.

Generally changes to the realities of the game are well-planned, typically in the direction of allowing more stories to be told. The Living Land, the low-technology reality of dinosaurs and lizardfolk, now has lost wonders within it. The original version of the reality was useful for two stories — “escape the Living Land” and “retrieve something or someone left behind in the Living Land” — but now fragments of mysterious other dimensions appearing among the mists open the door to new story shapes. They allow for a new kind of sublimity, perhaps, a new kind of awe, a new way to thrill players.

Some updates reflect a new way of thinking about the genres they reflect. The Cyberpapacy’s been modernised to accomodate the way the internet actually works while still keeping the core of violence and suspicion involved in the very 80s genre of cyberpunk. The Cyberpope has gamified religion while maintaining constant surveillance across his realm — one gains piety points for listening to a sermon, saying ‘Amen’ at the appropriate points, and so forth. Conceptually this strikes me as giving the realm a veneer of YA dystopia, and leads me to wonder how much of a distinction there necessarily is between that and cyberpunk.

The horror realm of Orrorsh is moved from the South Pacific to India, keeping the overlay of patriarchal and especially colonial horror involved in the nineteenth-century gothic: part of the horror of that reality is the gender norms and the racism implied in the attitudes of the old stories. Meanwhile, Pan-Pacifica is a major redevelopment of a realm formerly known as Nippon Tech, and if the old version was overly shaped by late-80s fears about Japanese economic dominance, the new realm wonderfully adds to the mix of genres in the spy-centred realm. Hong Kong action, Korean revenge drama, zombie outbreaks, wuxia, espionage — there’s a lot going on here, and the mix works. As it becomes easier to see movies and find stories from around the world, Torg reflects that in its realities.

The global scale of the game’s powerfully relevant now, more than it was in the 1990s. There are more stories from more different people and more different cultures more frequently told and more easily heard. A game about stories will reflect that reality. It’s easier to learn about the world and incorporate that into an evening’s play. Of course it will be partial and limited knowledge. But it encourages storytellers to learn new things. Preparing a character background that may lead into an adventure led me to browse around Google Earth and other sites learning about the history and geography of Saint Petersburg. If I still know very little about the city I at least know more now than I did. The shaping of a story about different realities invading the world leads one to better know part of the reality of the world as it is. It’s a paradox, but a useful one.

The global scale of the game’s powerfully relevant now, more than it was in the 1990s. There are more stories from more different people and more different cultures more frequently told and more easily heard. A game about stories will reflect that reality. It’s easier to learn about the world and incorporate that into an evening’s play. Of course it will be partial and limited knowledge. But it encourages storytellers to learn new things. Preparing a character background that may lead into an adventure led me to browse around Google Earth and other sites learning about the history and geography of Saint Petersburg. If I still know very little about the city I at least know more now than I did. The shaping of a story about different realities invading the world leads one to better know part of the reality of the world as it is. It’s a paradox, but a useful one.

Torg Eternity presents an intelligent reworking of a storytelling system that struck deep into me years ago. Working with it so far has already reminded me of the value of its themes and the power of its imaginings. The nature of life in these later years has meant that it’s taken more scheduling effort to set up an actual play session than when I was younger; but things proceed at their own pace. Much as I’ve written about the game already I’ll have more to say once the group’s been assembled, the dice set rolling, the cards put in action. Once the story’s set in motion and the Possibility Wars begun again.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Torg was a game that I always wanted to try. Back in the day when it came out my group just couldn’t invest the money and effort.

That said we did go for Rifts which cost us in time and effort anyway…

Reading this article has been really informative. It reminds me I have the Torg novels, perhaps the time has come to actually read them.

The updated game sounds interesting. Will be keen to read part two and hear how it played.

TORG was a game I played in the sunset of my first gaming years. I remember it as rich, entertaining and ambitious. You encourage me to seek it out again.

I loved the concept of TORG, along with RIFTS and other “Cross-Genre” experimental attempts. That’s what it’s about… Having a caveman next to Buck Rogers next to King Arthur, etc. And it pulled it off quite well, IMO.

Like most I wasn’t able to really play it – most other RPG’ers were into D&D if in it for the long term.

I especially liked the “Tharkhold” – aka “Techno+Horror” one.

I never really got into Torg, but I remember seeing Torg & Earthdawn on store shelves back around 1990-1991 and they were part of that early wave of RPGs that was raising the bar on production values (glossy pages, full-color art throughout, etc.).

Thank you for the article. I first picked up the game in Spring of 1990 (I believe it was, anyway), or shortly thereafter. I have loved the game from the very beginning and I appreciate what you’ve written about it. Nicely done, sir.

Thanks for the comment on this old article Paul. Glad you find it useful.

Do you still play?