The Quatermass Experiment: The Shakespeare of Sci-Fi Television

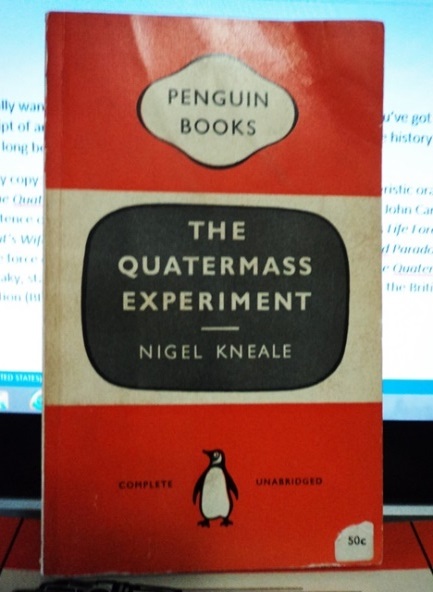

One of the most influential series in early television has actually made its way into science fiction history as a book. You can see my copy below: The Quatermass Experiment by Nigel Kneale, a plain 1959 paperback with the classic Penguin orange, cream, and black cover.

Ridley Scott’s Alien, John Carpenter’s The Thing, the very existence of Doctor Who, not to mention 1980s-1990s films such as Life Force, Species, and The Astronaut’s Wife, and contemporary films such as Under the Skin, Life and The Cloverfield Paradox, where alien invasion takes the form of infection and transformation – all these are different faces of a genre that began with The Quatermass Experiment in the shaky, static-filled first days of black-and-white television – back with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in the years after World War II.

In 1953, Nigel Kneale was a young writer and actor on the make. He had won an award for his 1949 short story collection Tomato Cain (a book which includes, among more naturalistic tales, portraits of vengeful nature and ancient supernatural evil that foreshadow his later works for TV and film). After graduating from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Kneale did some acting, but he had more success as a writer in the emerging field of television.

The BBC had been pioneers in developing television technology, broadcasting as early as 1932. They shut down their television operations during World War II, but after resuming in 1946, they rehired one of their producers from the 1930s, the Austrian-born Rudolph Cartier, who felt that this new medium should be liberated from the stagey, claustrophobic environment to which popular wisdom said that it was confined by its technology. Cartier found a receptive collaborator in Nigel Kneale, and after several programs together, in the summer of 1953 the duo were asked to supply a serial (today, we would call it a mini-series) to fill a six-week gap in the BBC’s programming schedule.

Challenged to make the best of this new medium, Kneale responded with his own story about new technology. His character Bernard Quatermass, the director and head scientist of the fictional British Experimental Rocket Group, launches the first men into space: astronauts Charles Greene, Ludwig Reichenheim and Victor Carroon are sent on a voyage that is supposed to take them 1,500 miles up, to orbit the earth and come straight home. Instead, the rocket swerves off course, shoots out past the moon, and doesn’t reappear for more than two days. When it crash-lands in south London, taking out a strip of abandoned row houses (the trauma of the London blitz is close to the surface in all the Quatermass serials), the stage is set for science fiction’s most famous locked-room mystery.

Although the ship has been sealed since takeoff, only Victor Carroon emerges, dazed and delirious. His fellow astronauts Reichenheim and Greene are nowhere to be found. Carroon, moreover, has changed in inexplicable ways. Confined to bed, his delirium deepens, his body temperature is abnormally low, his skin “seems swollen. Coarsened.” Even his bone structure seems different; so are his fingerprints. Plus, amid his confusion and disorientation, it seems that Carroon is now able to speak German – just like Ludwig Reichenheim.

The weight of evidence causes Quatermass – paired with Scotland Yard’s Inspector Lomax to solve the mystery – to theorize the existence of a kind of creature that science fiction cinema, and certainly television, had never previously depicted:

Lomax: “A living thing … ?”

Quatermass: “But not as we know life.”

“Able to pass through solid steel?”

“Like a cosmic ray. But alive.”

“Invisible …”

“To men. Our eyes are limited.”

“Able to destroy.”

“To change… to remake other living things.”

“An intelligence, then? Higher than ours?”

“Different.”

“And if it were… if it entered the rocket out there… then when everything had happened, it just … went away?”

“Perhaps… it stayed. [Their eyes meet.]

“You don’t mean… him?”

Whatever it is, it’s stayed all right, and has absorbed the essence of Greene and Reichenheim into the body and mind of the sole survivor. If the ensuing plot seems familiar – Carroon escapes confinement, and Scotland Yard, along with Quatermass and the Rocket Group team, frantically search London as the astronaut changes into something far from human – it is because so many works in the last sixty-plus years have been adapted from the template that Nigel Kneale designed.

From the original 1953 television production of The Quatermass Experiment.

Quatermass (Reginald Tate) and Judith Carroon (Isabel Dean) help astronaut

Victor Carroon (Duncan Lamont) from the crashed ship. The budget was

too low for the BBC to make their own space suits, so they

high-altitude flying gear from the Royal Air Force.

It was a template created in haste: the first of The Quatermass Experiment’s episodes were written, rehearsed, and performed live on television before the later episodes were written; in fact, before Kneale had any idea where the series was going. For all that, he managed to end The Quatermass Experiment with a bang – with a scene that become the most famous, as well as the most problematic, in the series: the climax in the last minutes of episode six.

After killing several people via a touch that “attacks the organic structure … a sort of digestion,” breaking into a pharmacy and mixing up a potion of poisonous chemicals that he drinks without ill effect, and laying waste to a park full of ducks, Carroon has mutated into an enormous mass of carnivorous vines and creepers, and takes refuge in of all places, Westminster Abbey. The monster’s existence is revealed, appropriately, on live TV, as a frail, elderly architectural scholar narrates a BBC documentary about the Abbey. Part of the Kneale/Cartier genius was their awareness of the power of the film-within-a-film as a narrative device (those who watched The Quatermass Experiment also saw excerpts from an onboard film and tape recording archive that revealed vital clues to the tragedy aboard the doomed spaceship). At his best, Kneale had an impressive command of the power and rhythm of the English language, and it is this short passage in this three-hour script that may best qualify him for the (admittedly awkward) title of the Shakespeare of Sci-Fi Television.

This is admittedly an extravagant claim, but one that’s worth making. We value Shakespeare for the sheer beauty of his words as they are read, or spoken. Kneale’s dialogue in Experiment, and the other Quatermass television scripts, doesn’t approximate the delicacy and referential breadth of Shakespeare’s. It was never intended to, especially since the mise-en-scene of The Quatermass Experiment draws so much of its power from its naturalism, from the everyday qualities of its setting and characters. But in terms of sci-fi TV and cinema, Kneale’s work can claim equal impact to Shakespeare’s influence on theatre, in the way his scripts fully utilize the medium, in the way they demonstrate infinite capacity to be heeded, re-molded, and assimilated by other artists, and above all in the way that each of his original Quatermass serials present figures that place Kneale squarely in the historic tradition of theatrical tragedy.

Quatermass is not a tragic figure himself. He always prevails (more or less) in the end, but inevitably he suffers a lot, he gives up a lot, and he fails to save everyone. Although The Quatermass Experiment, and its two sequels, resolve on what might be called happy endings, the pain of the characters as they move through the narrative, the realizations they achieve, and the sacrifices they make, would readily fit into ancient Greek tragedy, into Shakespearean tragedy, or into the working-class tragedies of Britain’s “angry young men” of the 1950s – a group to which, one might argue, Kneale belongs – bound, as he is, to such writers as John Osborne, Alan Sillitoe, John Braine, and Shelagh Delaney not only by time and place, but by his underlying themes of ambition, individual responsibility, and the incursion of huge, impersonal forces into everyday life.

That said, although it moved millions of listeners in 1953 Britain who saw it on TV, it is almost impossible to find the speech itself outside the Penguin version of The Quatermass Experiment. This is because of a further complication in the complex history of this seminal work: it reached its widest audience through its film version, which was titled The Quatermass Xperiment in the UK, and was released in North America under the delicious title The Creeping Unknown. This version deletes the penultimate speech altogether: not a man to mince words, Brian Donlevy’s Quatermass simply diverts all the electricity in London into the Abbey so that the Carroon monster, nesting high atop a renovator’s steel scaffold, can be electrocuted and die screeching amid smoke, sparks and flames.

The ending of the original TV play is, dramatically, much harder to pull off: in this version, while the Rocket Group staff replay the sound recordings from the doomed spacecraft (they know this will have a profound effect on the stricken Carroon), Quatermass calls upon the creature’s human side to cast off the invading influence:

Quatermass: You will overcome this evil. Without you it cannot exist upon the earth… it can only know by means of your knowledge… understand through your understanding. It can only exist through your submission. Victor Carroon… Ludwig Reichenheim… Charles Greene… you are resisting this thing. Now go further… go further! With all your power and mine joined to yours… you must dissever from it… send it out of earthly existence! You… as men… must die! Greene! Reichenheim! Carroon!

In short, with the help of electronic media, Quatermass persuades the monster to turn upon itself, and commit suicide by sheer force of will. It’s an epic moment in the literature of filmed sci-fi, but unfortunately, there’s no document of the original broadcast. According to the published script, the scene is intriguing, delivered against the backdrop of a horrifically transformed Westminster Abbey:

… something can be seen of the memorials of Poets’ Corner, now almost totally hidden by massive sections of the Thing. This part of the Abbey is like dense jungle – columns, shapeless with ponderous growths, huge boles dependent from high above, matted fronds – but all actively alive, throbbing, twisting, rustling.

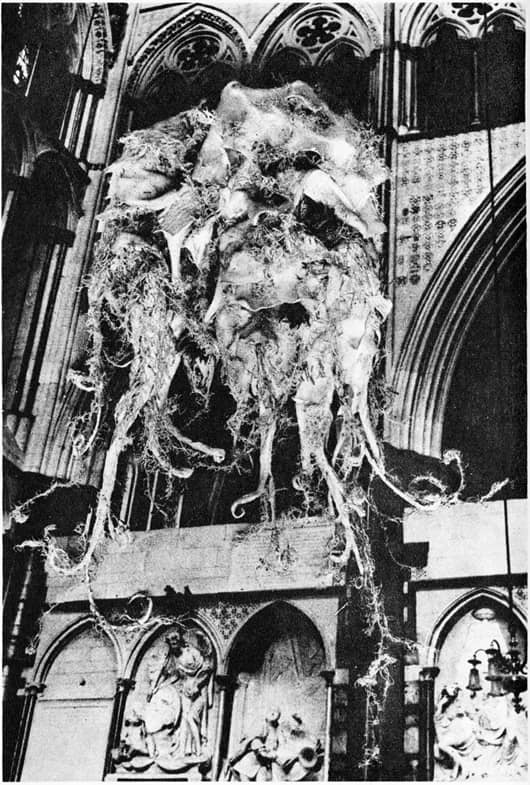

The budget for the Quatermass serials, however, was famously low, and it’s hard not to wonder what the audience actually saw. The book includes the picture of “The Thing in Westminster Abbey,” as it appeared in the series:

“The Thing” that gave nightmares to a generation of British TV watchers was, famously, one of the Kneale household’s gardening gloves, which Nigel and his wife Judith Kerr had decorated with twigs and moss, and shoved through a hole cut into a photographic enlargement of Westminster Abbey. In the published book the monster changes, within a few hundred words, from “a dense thicket of stems knotted with fungoid tufts, swaying round the shaft of a marble column,” to, upon its death, a roomful of “drying husks … Like falling leaves, tiny fragment of the Thing start to drift down.”

What did this look like on screen? I have never found an account of the ways, aside from the glove, in which the appearance and destruction of “the Thing” played out in the original serial. It could be that aside from the glove-monster, the BBC production team managed to evade special effects altogether. This was the route taken in the network’s live 2005 adaptation of The Quatermass Experiment, where the monologue is placed front and centre. As Quatermass, Jason Flemyng gives a moving performance, in a setting of Beckettian starkness. An empty and darkened Tate Gallery substitutes for the Abbey, and with minimalist delicacy, the monster is represented only through sounds. We experience its death like this: out of the living darkness that surrounds Quatermass, Carroon and the other two astronauts appear, momentarily spotlighted, and then fade away for good.

There is no full document, however, of the original 1953 production. After recording the first two episodes on 35-mm film, the BBC decided to cut costs, and didn’t record any more. The first two episodes are available on DVD (at this writing, I’ve just seen them on YouTube), but the fuzzy, low-res black and white, and sound recording that often favors every noise on the set except the voices we’re trying to hear, remind us all too acutely that this pioneering series was made with TV equipment that actually dated from the 1930s.

That makes this cheap mass market paperback all the more valuable. Certainly, over the decades, my copy has become one of my most valued books. A 1979 reissue, with a colour cover and a foreword by Kneale, is evidently now just as rare. But the feeling of the published script has not aged or faded with time. In many ways, The Quatermass Experiment introduces a space age that begins with new hope for the future, but ends with new depths and definitions of loneliness. By the play’s end, Victor Carroon’s wife Judith, in love with the rocket group’s physician Gordon Briscoe, has rejected her lover out of loyalty to her husband, who is literally becoming a monster; the three astronauts are dead; and Quatermass is isolated by his mounting guilt, as he takes on more of the blame for the fate of his friends and colleagues. At the end, having led his team to find and vanquish the Carroon-creature, he stumbles off by himself to lean on a low wall outside the Abbey, looking “out into the night sky.”

The success of the televised “Experiment” led to two more seminal Quatermass mini-series, which also had their scripts published by Penguin, each of which I will write about in future posts.

David Neil Lee lives in Hamilton, Ontario, where his Lovecraftian YA novel The Midnight Games won the city arts council’s 2015 Kerry Schooley Award for the book that “best conveys the spirit of Hamilton.” He has recently completed a Ph.D. in English at the University of Guelph, and is working on a Midnight Games sequel, and other books. His last article for Black Gate was a review of Kong – Skull Island. Visit him at davidneillee.com.

I remember purchasing the VHS of the tv play Quatermass and the Pit and being struck by how inventive the production was despite the crudity of the tools at hand. It is a very, very good piece of television.

Afterwards, I discovered there were three script books of the BBC Quatermass productions, and happily, found all of them very cheaply.

The fellows behind almost all the Doctor Who DVD releases worked to restore the extant episodes of all 3 BBC serials. There’s a fascinating article, with photos, covering the work they did, written by two of the people behind the release, here: http://www.impossiblethings.net/restorationteam/quatermass-article.htm

Thanks, Robert, for the link and comment. The Quatermass trilogy has certainly been influential considering how quickly and cheaply the original serials were done. Once I found out about those Penguin scripts I spent a summer vacation being driven around small towns in the Canadian prairies c. 1965, poring through used-book stores looking for Quatermass and the Pit.

[…] The Quatermass Experiment: The Shakespeare of Sci-Fi Television April 2018 […]

[…] I’ve recently posted the second of my Black Gate blog posts. The subject of this one is the iconic 1950s BBC-TV serial The Quatermass Experiment. […]