Godzilla Acid Trips Thru Tokyo: Godzilla ‘77, a.k.a. Cozzilla

Do you remember the time Godzilla dropped the brown acid while watching Mothra’s colored wings, and then Raymond Burr joined him and they tipped back a few cases of wine from Burr’s personal vineyards, while Burr told the plot of Perry Mason episodes backwards, where Mason would undo a court decision, Paul Drake would put evidence back in place, and at the climax a dead body would return to life?

None of this actually happened — but something close to it did. It involves the Italian film industry (doesn’t it always?) and the director of Starcrash and the Lou Ferrigno Hercules movies. It’s called Godzilla il re dei mostri (“Godzilla the King of Monsters”), a.k.a. Cozzilla after its creator, Luigi Cozzi — and it’s one of the strangest and least known chapters in Godzilla history. Not as much an acid trip as Godzilla vs. Hedorah, but in that ballpark.

It starts with the 1976 King Kong. The Dino De Laurentiis remake of the ‘33 giant monster classic may not be much good (I’ll give composer John Barry a hand for his score, and I like Jeff Bridges’s beard), but it took in such a big overseas haul that it triggered a mini-monster boom in Europe and Asia. We can thank its success in Japan for getting the momentum going to restart the Godzilla series, resulting in The Return of Godzilla in 1984 and the better Heisei movies that followed.

But King Kong ‘76 also shocked into life an Italian take on Godzilla that most people are unaware exists. Godzilla il re dei mostri isn’t exactly a “new” film. It’s an Italian colorization and re-edit of the 1956 U.S. reshoot and re-edit of the 1954 Japanese Godzilla, only now with tie-dye colors, a mishmash of stock footage, and Tangerine Dream-esque electronic music. Because that’s what those two earlier versions of Godzilla were missing.

Here’s how it went down. Italian director Luigi Cozzi, who often used the Anglicized pseudonym “Lewis Coates,” had experience purchasing classic science-fiction movies and showing them in Italian theaters to great success. He wanted a wide re-release of a giant monster film to capitalize on the new King Kong. He first tried to license the British film Gorgo (1961) from the King Brothers, but their asking price was too high. Cozzi then reached out to Toho to license Godzilla. Cozzi had seen the film in theaters as a child and loved it, but it hadn’t shown in Italy since 1959. Toho agreed to license the film, but for reasons the studio didn’t elaborate, they could only provide Cozzi with a negative of Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, the 1956 U.S. version directed and edited by Terry Morse with additional footage featuring Raymond Burr.

But Cozzi couldn’t get an Italian distribution company to go along with his Godzilla re-release idea. The problem: black and white. Distributors didn’t think an audience would turn out for a B&W film, no matter how big-name the monster.

So Luigi Cozzi got a trippy, ambitious idea. He’d turn Godzilla, King of the Monsters into a color movie!

Colorizing black and white film stock is almost as old as cinema itself. Georges Méliès hand-colored many of his films, such as 1902’s A Trip to the Moon, and color tinting was a common practice in silent movies. But before the invention of the digital computer colorization techniques we all know and hate today, adding color to monochrome film was a time-consuming and difficult process.

In an interview with Sci-Fi Japan, Cozzi explained how he came up with the way to colorize Godzilla:

It was at this point that I did think of coloring the old black and white Godzilla movie, as at the same time I was experimenting with stop motion optical machinery in order to create some special visual effects for a sci-fi movie project which later became my movie Starcrash. I had the idea to colorize with stop motion every single frame of the Godzilla movie. I did a test, it worked and so I decided to go ahead with this crazy idea.

Cozzi used a process he called “Spectorama 70.” It has nothing to do with 70mm — the number “70” was often slapped onto film processes to make them sound grander. It was a quick way to add color to film by laying gels over blown-up images of each frame and coloring them, then photographing the images with a stop-motion camera. Cozzi worked night and day for three months with stop-motion photographer Armando Valcauda and editor Alberto Moro to finish the project.

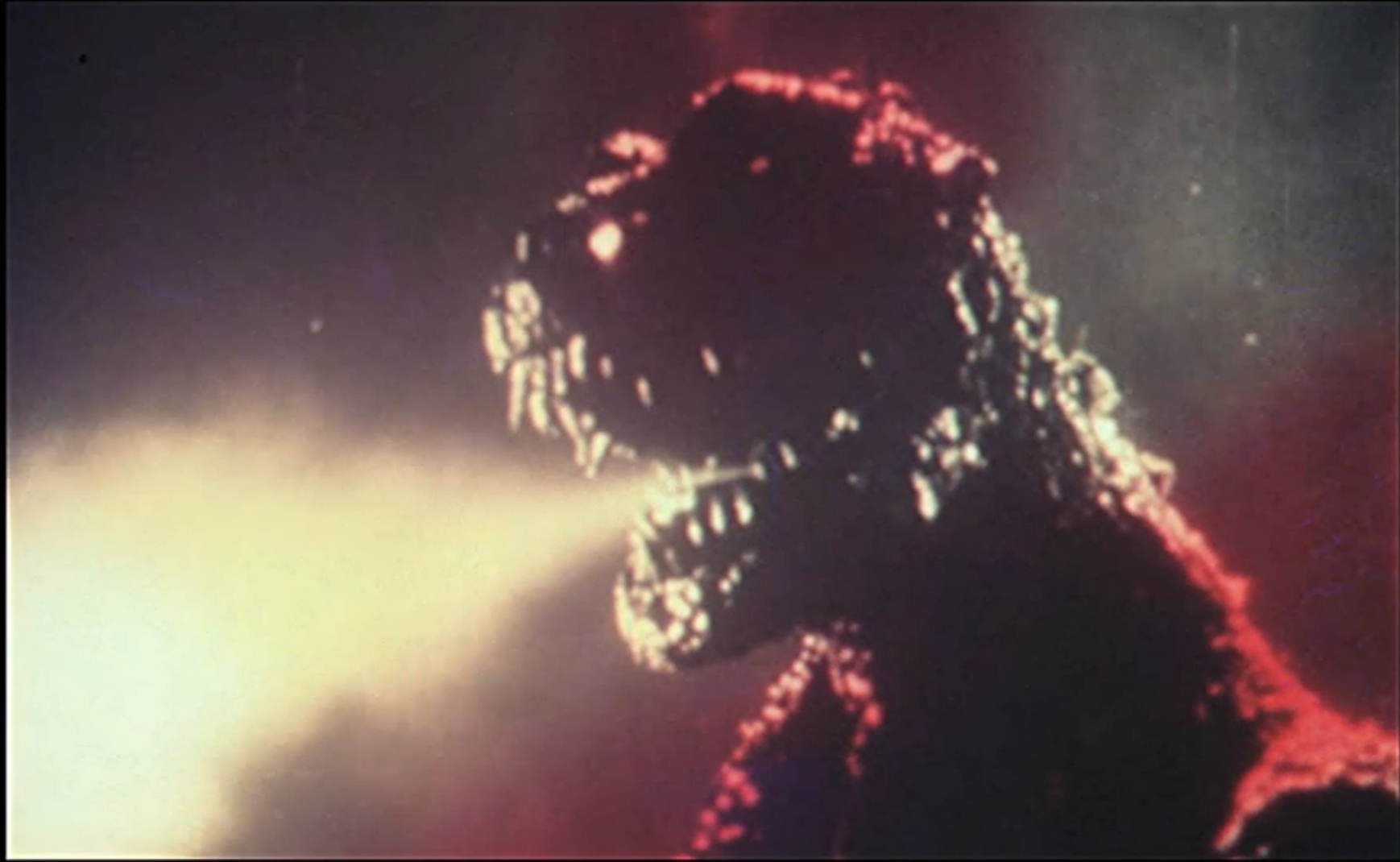

The colors for Cozzilla went down in large swaths rather than meticulously filling in the lines. Blue over the top of the frame for sky, green lower down for grass, yellow for direct sunlight, and other hues to make vague matches for what the eye might expect from a color image. Of course, the results are nothing like what the eye might expect. It’s a radioactive rainbow that feels like watching the movie through a kiddie kaleidoscope. I remember playing with the tint levels on color TVs as a child to make everything look strange; this is a feature film version of that, but worse — or better, depending on your current state of consciousness.

The colors for Cozzilla went down in large swaths rather than meticulously filling in the lines. Blue over the top of the frame for sky, green lower down for grass, yellow for direct sunlight, and other hues to make vague matches for what the eye might expect from a color image. Of course, the results are nothing like what the eye might expect. It’s a radioactive rainbow that feels like watching the movie through a kiddie kaleidoscope. I remember playing with the tint levels on color TVs as a child to make everything look strange; this is a feature film version of that, but worse — or better, depending on your current state of consciousness.

The wild color scheme isn’t constant. Interior drama scenes often rely on a basic sepia color tint, similar to a silent film. But the uncanny intrusions of purple and red into sequences where there’s no justification for it keeps the movie always on the edge of tilting back into psychedelia no matter what’s on screen.

Turning Godzilla, King of the Monsters! into a simulacrum of color wasn’t the end for Luigi Cozzi. Our man in Rome took extra experimental steps, maybe after calling up his friend and professional collaborator Dario Argento, director of Suspira, and asking him how he could make this even weirder.

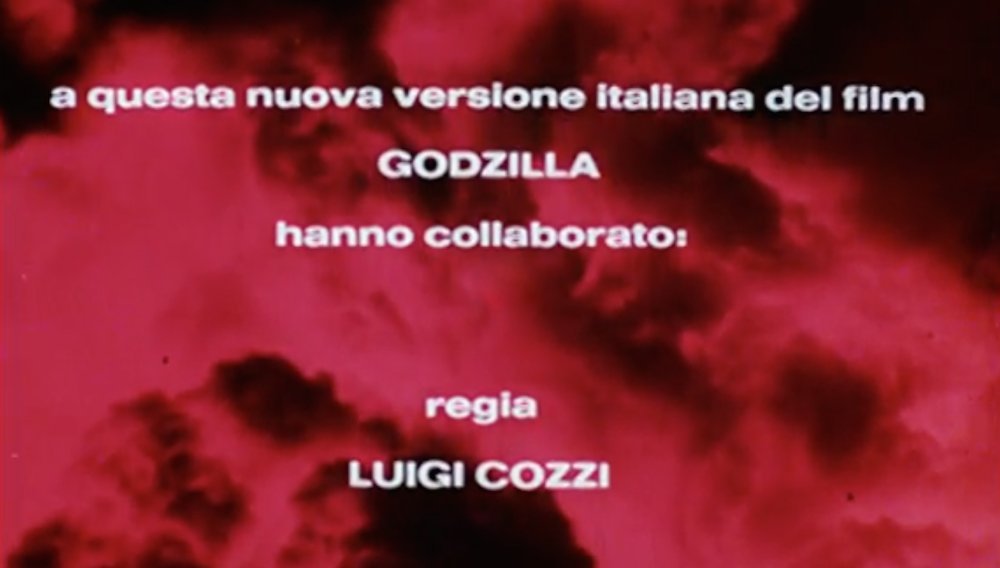

Godzilla, King of the Monsters! clocks in at a B-movie length of seventy-nine minutes. Cozzi needed his version to be at least ninety minutes for release. To make up the extra time, Cozzi created a new prologue, titled “Hiroshima, 6 Agosto 1945,” which links stock footage of pre-war Japan, a bomber, glowing atomic mushroom clouds, and then images of a ruined city and actual dead bodies charred from the blast. I think some of the aerial footage of a bombed city is from Germany, although I’m not certain. The five-minute prologue plays out to electronic music that sounds like Barry De Vorzon’s theme to The Warriors. The title sequence (now with three credited directors: Ishiro Honda, Terry Morse, and Luigi Cozzi) appears over roiling multi-colored clouds and a jarring overlay of Godzilla roars.

There are many more stock images to come: Extra shots of clouds and water flooding when Godzilla comes ashore on Ohto island. The Japanese Imperial Navy doing … something … in the middle of the depth charge scene. More explosions! More falling buildings! More horrifically scarred corpses! One of the strangest alterations is when Godzilla rises from the sea near a pleasure boat. Cozzi includes images of people rushing to lifeboats to escape a burning military vessel, but also slows down the Japanese footage for a hallucinogenic effect.

The intent of these changes, aside from expanding the runtime, is apparently to hammer home (as — hard — as — possible) the nuclear theme of Godzilla. Of course, it just makes everything loopier. There’s an Ed Wood sensation to all this: a whole-hearted but half-baked looting of every available piece of stock footage. I’m amazed no buffalo made it into the final cut. (“Godzilla is attacking the city — but he’s scaring the buffalo …”)

The intent of these changes, aside from expanding the runtime, is apparently to hammer home (as — hard — as — possible) the nuclear theme of Godzilla. Of course, it just makes everything loopier. There’s an Ed Wood sensation to all this: a whole-hearted but half-baked looting of every available piece of stock footage. I’m amazed no buffalo made it into the final cut. (“Godzilla is attacking the city — but he’s scaring the buffalo …”)

The new material isn’t only war footage. It also comes from other movies. Cozzi had access to a pile of classic SF films, and plenty of extra shots of their destruction and mayhem flash through the rampage scenes. This includes the second Godzilla film, Godzilla Raids Again (1955, released in the U.S. as Gigantis the Fire Monster) and The Day the Earth Caught Fire. Cozzi padded out the scene of Godzilla’s first land attack with footage from John Frankenheimer’s The Train (1964), one of Cozzi’s personal favorite movies. During the finale in Tokyo Bay, Dr. Serizawa stops for a moment to enjoy a shark fighting an octopus, courtesy of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.

Some of this footage slots seamlessly into the movie thanks to the crazy color scheme covering up differences in film quality. Other additions are glaring, even to people unfamiliar with Godzilla. Why are U.S. warplanes attacking Godzilla? How did the Japanese Self-Defense Force expand to include every weapon ever used in World War II, all firing at once? When did Godzilla teleport to the London blitz?

Cozzi had to supersize the sound as well to appeal to a contemporary audience used to stereophonic soundtrack. He invented another process, Futursound, to give Godzilla, King of the Monsters! an eight-track magnetic soundtrack with bonus Sensurround-style effects channeled through giant speakers placed on theater floors. Godzilla’s footfalls and roars got a sonic BOOM! effect. There’s also a barrage of wind and screaming sounds playing for long stretches, creating a sonic soup to match the colored soup on the screen. The sound effects are mostly lost when seen on streaming. Only the big theaters in Rome and Milan were able to duplicate the spectacle of the sound changes.

Most of Akira Ifukube’s score remains in the picture, minus the parts already cut for the 1956 version. But composer Vince Tempera wrote new music for the extended scenes and new montages, performing the music himself on synthesizer. The main influence was the music of Goblin, a prog rock band that provided famous scores for many of Dario Argento’s films.

Cozzilla isn’t an easy movie to watch in full (at least while sober). The city rampage seems to go on forever, not only because of the stock footage overload but because of repeating shots of Godzilla breathing radioactivity and slowing them down. But some of the glowing red and yellow auras during the destruction in Tokyo create an eerie, impressionistic beauty that merges well with Eiji Tsuburaya’s special effects. There are other moments of strange loveliness, such as a fire bowl burning with supernaturally red flames in the night wind on Ohto island. Unfortunately, the color scheme often renders dark scenes visually incomprehensible mulch, and the shifting popsicle hues and rapid cuts are jarring enough to induce headaches.

Cozzilla isn’t an easy movie to watch in full (at least while sober). The city rampage seems to go on forever, not only because of the stock footage overload but because of repeating shots of Godzilla breathing radioactivity and slowing them down. But some of the glowing red and yellow auras during the destruction in Tokyo create an eerie, impressionistic beauty that merges well with Eiji Tsuburaya’s special effects. There are other moments of strange loveliness, such as a fire bowl burning with supernaturally red flames in the night wind on Ohto island. Unfortunately, the color scheme often renders dark scenes visually incomprehensible mulch, and the shifting popsicle hues and rapid cuts are jarring enough to induce headaches.

In fairness to Cozzi, image and color clarity probably weren’t issues during 35mm theatrical screenings. Many of the problems are from watching an old print on a computer monitor. Overall, Cozzilla is a far superior “colorized” movie experience than any of the later computer-colorized film. The reason is straightforward: Cozzi’s film isn’t attempting to make the color appear realistic at all. The color instead creates a recontextualized black-and-white film that can stand as its own bizarre art statement. Trying to colorize classic movies the way Ted Turner did in the ‘80s can never look good because every visual decision originally made on those films was based on shooting them in monochrome: camera work, lighting, costuming, set design. The digital color tries to pretend it’s realistic, but is instead disconcerting and unnatural. With Cozzilla, disconcerting and unnatural are what it’s all about. It’s not a replacement for the original or pretending it’s somehow better. It’s weird and knows it, like a Warhol pop-art experiment. I’d certainly watch a 35mm showing with the right sound system if such a thing ever happens in the U.S. Unfortunately, Luigi Cozzi believes the original magnetic soundtrack is lost.

Godzilla il re dei mostri screened commercially in Italy and was a financial success. “Not a fortune,” Cozzi recalls, “but enough to make a good movie.” The only other territories where it was commercially shown were Turkey and (yes!) Japan. Part of Cozzi’s original deal with Toho was that they would own the rights to the negative of his color version. This has prevented Cozzilla from popping up elsewhere, although I think general public interest is the major barrier against a re-emergence. Cozzilla has occasionally screened in Italy since 1977, but until recently was available in other countries only on a blurry bootleg VHS that was later uploaded to YouTube. In 2017, a “restored” version in higher quality turned up on the Internet Archive. Somehow, it’s still there as of March 2018, although it lacks subtitles for the Italian dub. Indulge freely if you wish, but please do not operate heavy machinery afterward.

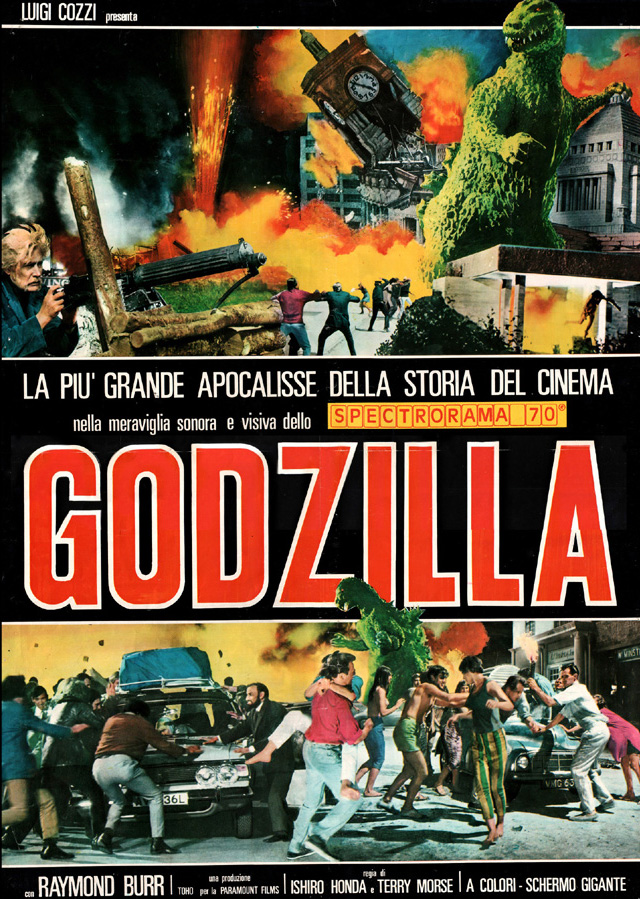

An interesting postscript: the poster from the Italian release of Cozzilla became the cover for issue #1 of Fangoria in 1979, which featured an article on the Godzilla series by Ed Godziszewski.

By the way, Cozzilla wasn’t the only time Godzilla, King of the Monsters! was altered and given a re-release. The enormous international popularity of the U.S. version led to it being shown commercially in Japan. It was released under the title Monster King Godzilla (Kaiju o Gojira) in May 1957, giving Japanese audiences the opportunity to watch a dub and re-cut of their own film. As an extra gimmick, Toho made the movie “widescreen” by masking off the top and bottom of the original 1.33 image and enlarging it, frequently cutting off the top of Godzilla’s head and removing most of Raymond Burr’s impressive acreage of forehead. I’ve never seen this other oddity, and I’m fine with that.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. His most recent publication, “The Invasion Will Be Alphabetized,” is now on sale in Stupendous Stories #19. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a marketing writer. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Am I committing a cardinal sin by admitting that I have never liked Godzilla in ANY of his/its incarnations? I was in my early teens when I saw my first Godzilla film (probably “Mothra Vs. Godzilla” in ’64), and the only thing I recall from that is the two women who sang/chanted Mothra’s name (is that 54-year-old memory accurate? Haven’t seen the film since…). Maybe it was the cheesy special effects, but that rarely ruined earlier films I saw. It’s not the big ‘beast that conquered the world’ concept that bothered me; on the contrary, I liked the original “King Kong,” very much enjoyed the recent “Kong: Skull Island,” and liked the first entry in the “Jurassic Park” franchise. But I’ve just never been able to find that sense of wonder in Godzilla — except to wonder how he/it has managed to keep cropping up every few years or so. Please don’t feel I’m dissing any Godzilla fans; he just ain’t my cup o’ tea.

> Am I committing a cardinal sin by admitting that I have never liked Godzilla in ANY of his/its incarnations?

Yes.

Go say ten “Mahara Mothras.”

Seriously, however: Godzilla isn’t for everybody, and as a Godzilla fan I’m often painfully aware of this. (Ask most women I’ve dated the sort of strain this can place on a relationship.) But I spread the gospel of GODzilla nonetheless because I am called to it. The mystery of why Godzilla is so awe-inspiring and majestic to fans is often hard to describe, much like many fandoms.

Thanks, Ryan, for not trashing me! As I wrote that first response, I found myself recalling a film I’d seen two years before “Mothra/Godzilla” titled “The Magic Sword.” I LOVED that film, and kept it playing in my head for weeks (I was 11). I saw it again a few years ago, and couldn’t believe how silly it looked. Maybe if I’d caught Godzilla fever at the same age, I’d still be recalling it with fondness. But that’s the thing I love about Black Gate: there’s a little something here for EVERYBODY.