Will Eisner: Ahead of His Time

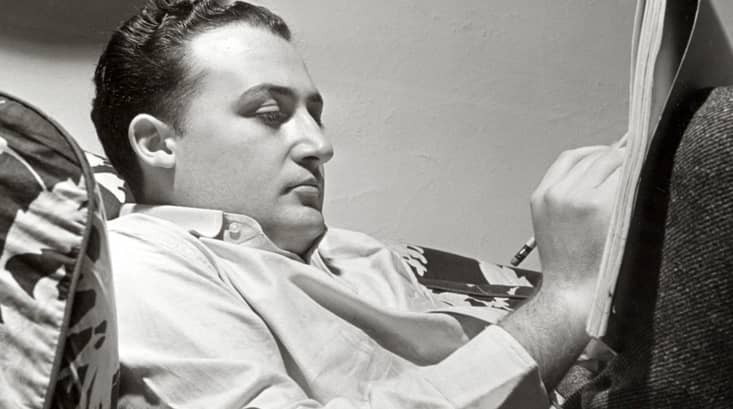

Will Eisner

We are all in the habit of communicating in shorthand (perhaps now more than ever, in this era of emojis and tweets and texting) and often toss out clichés and smooth-worn phrases without pausing to consider what they might actually mean. It can hardly be otherwise, seeing that we are all in such a damnable hurry. (To ask where, exactly, we are hurrying to can make people uncomfortable, so I won’t ask.)

For this reason it might be useful to take one of these everyday expressions and give it a precise definition. The common phrase I have in mind is “ahead of his time.” I picked an easy one, so easy I can define it in just two words: Will Eisner.

I know this is hardly a contentious judgment. In the comics field, to speak the name of Will Eisner is like calling on the Lord Jehovah in the Sinai Desert; there is no higher name to invoke. After all, this is the man the comics industry has named its most prestigious award after. But to call an artist “ahead of his time” (or “the greatest artist-writer ever” or “a revolutionary genius,” all terms regularly applied to Eisner) means nothing without some idea of just what the standards of that time were and exactly how the winner of such praise compares to the competition.

So to put some flesh on the bare bones of the accolade, let’s go back to 1950 and take a look at the doings of the two most iconic heroes of the time, or maybe of any time — Batman and Superman, and compare them with a story from 1951, featuring Eisner’s signature creation, the Spirit, from near the end of the character’s run. (There’s no need to ask what the great Marvel heroes were doing in those days — Captain America and the Sub-Mariner were in limbo, and the Lee/Kirby/Ditko characters that dominated the sixties hadn’t been created yet. Marvel wasn’t even Marvel — the company was still called Timely, and with the postwar contraction of the superhero market it had decided to drop costumed crusaders and focus on monster comics.)

[Click the images for Eisner-sized versions.]

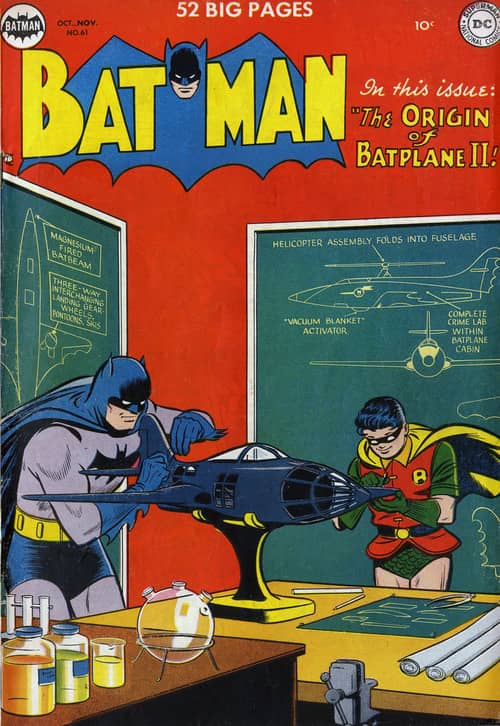

“The Origin of Batplane II,” Batman #61

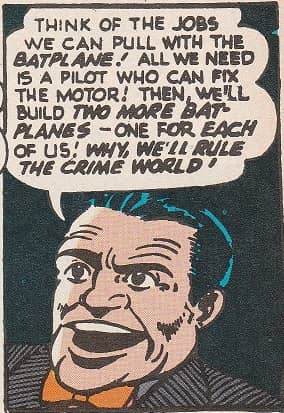

In “The Origin of Batplane II” (Batman 61, October-November 1950; story: unknown, art: Dick Sprang and Charles Paris), the fabulous Batplane falls into the hands of a trio of villainous brothers who use their airplane plant as a cover for their smuggling operations.

With the Batplane in their possession, the three stinkers use their factory to make two exact copies of the aircraft, so each brother can have his own; together, they aim to become the sky kings of crime. Soon, hijackings by plane and other aerial outrages abound. (Along the way, they use blackmail to force a dejected out-of-work ex-military pilot to help them with their evil schemes.)

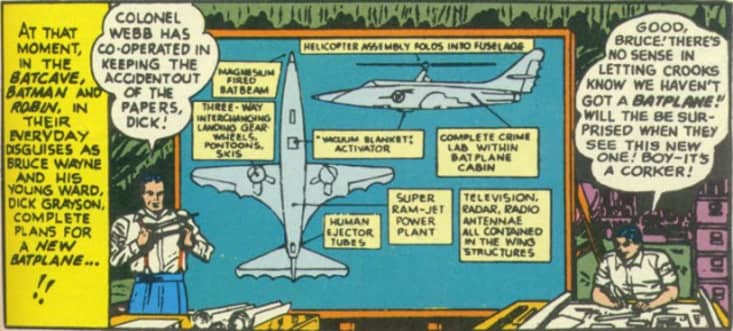

What do Batman and Robin do? Quickly design and build a new Batplane, of course — an improved model that can instantly transform from a fixed-wing aircraft into a Batcopter and even a submarine (or “Batmarine,” as you darn well knew it would be called).

Piloting the Batplane II over the skies of Gotham City, the Dynamic Duo make short work of their adversaries and find a job for the ex-military pilot to boot.

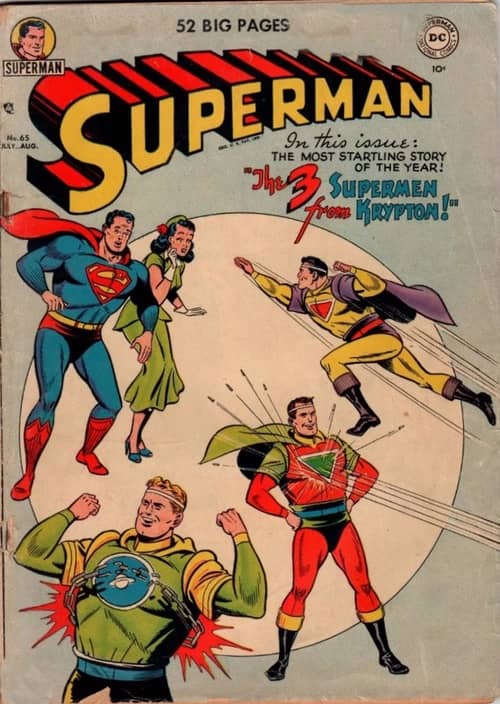

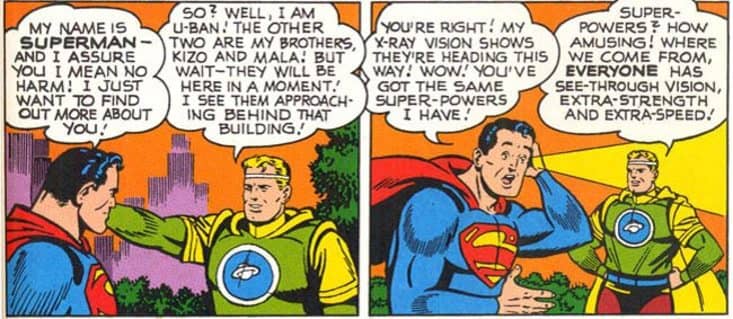

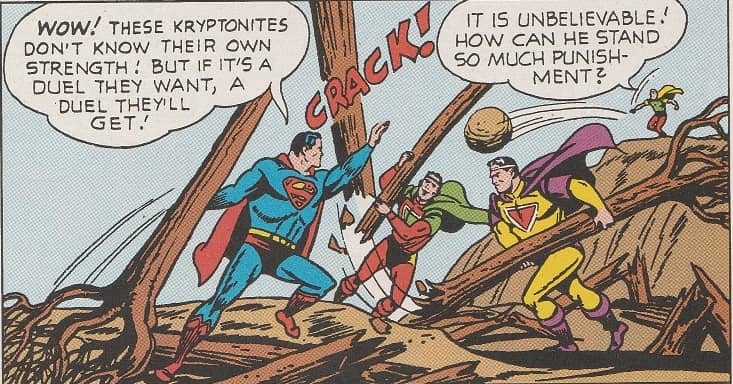

In “Three Supermen from Krypton” (Superman 65, July-August 1950; story: William Woolfolk, art: Al Plastino), the Man of Steel finds himself flummoxed by the sudden appearance of three Kryptonians (brothers again!), all intent on making themselves lords of earth.

“Three Supermen from Krypton,” Superman #65

They have a fair chance of succeeding, because under a yellow sun, they all have the same powers Superman himself has. (How did they escape the explosion of Krypton? They were put into suspended animation and shot into space for general nefariousness — by Jor-El himself, no less, a few years before the doomed planet met its fiery end. A chance meteor hit diverted their prison-rocket right to the middle of Metropolis. What are the chances?)

After a bit of inconclusive chest thumping, Superman makes a deal with them — they’ll go to an uninhabited island and battle each other, the loser leaving Earth for good. But it’s three against one — how will Superman prevail? At the end of a long day of battering each other with fists and trees and rocks, all four Kryptonians are prostrate with exhaustion. But Superman has enough juice left to generate a little super-ventriloquism. He uses it to trick his foes into turning against each other, and once the three interlopers have pounded each other into even greater fatigue, Superman stuffs them into a new suspended animation spacecraft that he cobbles together between one panel and the next and shoots them back into eternal exile.

These two stories are full of color, action that’s sometimes so speedy it’s almost incoherent, and pure Golden-Age goofiness (to put the most generous face on it), as when one of the planes Batman knocks out of the sky just happens to fall into a flatbed truck full of soft rags (even the writer concedes that this is a “miraculous stroke of luck”), thus preserving the crimefighter’s “non-lethal” reputation. All this is rendered in art that can be quite vigorous, but just as often appears crude and hasty.

Neither tale has any discernable shape or narrative rhythm, proceeding in fits and starts from one improbable or ridiculous thing to another. Half the time our heroes are caught up in frantic action: Superman repairs all the toppling skyscrapers in Metropolis in 1/4 of a second, zooms 1500 miles away to demolish a sinister machine of super-science, hurls huge boulders at his opponents, and takes a “split-second trip” to Malaya, the Archipelago Islands (?), and the Arctic Circle to get the ingredients necessary to duplicate Jor-El’s suspended animation formula. Batman and Robin use the Batplane to test out a new weapon for the Army, bail out of the Batplane when the weapon kills the engine (it’s comforting to know that military contracts work just the same today as they did seventy eight years ago), design and build a new batplane (which takes all of four panels), dogfight and defeat the three brothers — trying out both the new Batcopter and Batmarine features in the process — and finish up by restoring the embittered veteran to a useful place in society (which takes just one panel, thus perfunctorily dismissing the one element of embarrassing reality in the entire story).

|

|

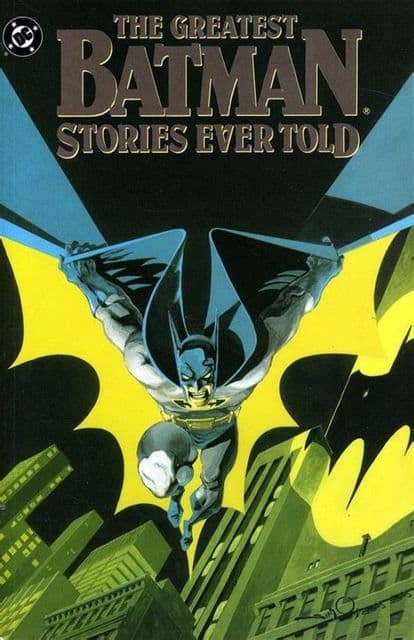

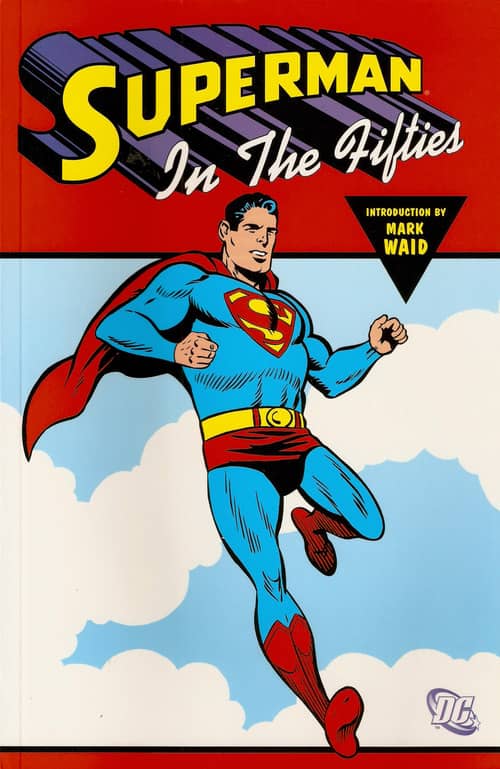

The other half of the time the protectors of Gotham and Metropolis are standing around listening to dull exposition by men in suits, or they’re vanishing altogether, obliterated by scenes of other characters’ flat-footed scheming or held rapt by leaden flashbacks (it takes over three full pages to recount the history of the Kryptonian brothers). Each story’s twelve pages go by quickly enough, but there’s little to hold on to once the tales are finished. And I have to assume that these are two of the better such stories of their era, pulling them as I did from The Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told and Superman in the Fifties, two nice trade paperbacks chock full of four-color fun. Thus, what we’ve seen is much better than the “typical” story of the time, because the typical story didn’t feature great characters like Batman or Superman, and while DC was the Rolls-Royce of comics, the productions of most non-DC publishers were quite unbelievably awful.

I don’t point all of this out to denigrate these stories or their underpaid creators, but rather to provide a standard against which to judge the work of Will Eisner. I love the great Golden and Silver Age characters and the sunny worlds they inhabited. At their best these comics had a freshness, optimism, energy, inventiveness, and lack of cynicism that’s very appealing even now. But as these two summaries show, these stories were manifestly for children, and not very sophisticated children at that. For all their virtues, they’re incapable of engaging an adult mind for very long on any level beyond that of nostalgia or a campy enjoyment of silliness for silliness’ sake. No one but a child could take them seriously for a second. This is neither a surprise nor a fault — of course Batman and Superman were written for children; in those days no one (with one exception, and I’ll bet you can guess who it is) had any idea of comic books being anything but disposable diversions for immature minds.

In 1950, that was the rule. Now let’s take a look at the exception.

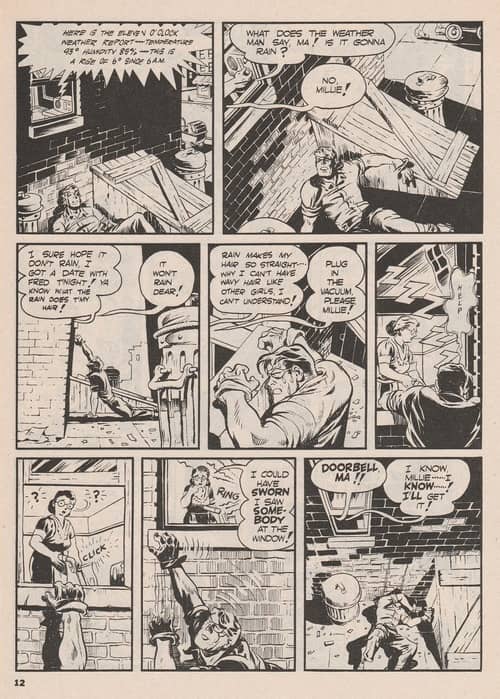

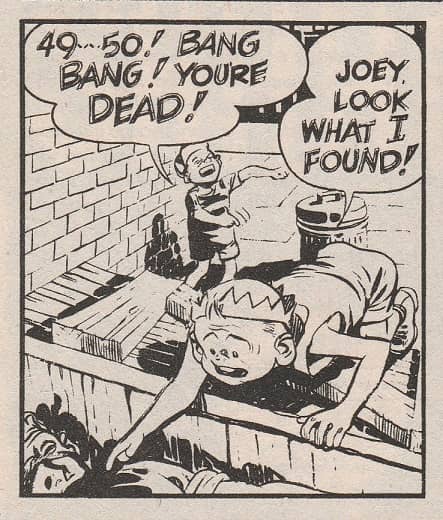

In “Heat” (July 15, 1951; story and art: Will Eisner), the Spirit doesn’t hit anyone with fist, tree, or boulder. He doesn’t pursue anyone, by land, sea, or air. He doesn’t construct an advanced airplane or suspended-animation rocket, or travel to the far corners of the earth. Instead, he lies in a narrow, garbage-strewn alley, slowly bleeding to death on the hottest day of the year. Two panels take care of the exposition — the night before, he was tailing his nemesis, the Octopus, when he was ambushed by the mastermind’s mob, shot, and left for dead. Now, upon regaining consciousness, the Spirit is too weak from loss of blood to crawl out into the open or to raise his voice loud enough to attract the attention of the people who are all around him.

And people are indeed all around him, and the contrast of the bustling life of the city with the impending death of the hero, of his desperation with the obliviousness of the people he is ostensibly protecting, is striking and memorable; it is, in fact, the point of the story. (Instead of being a chain of wild incidents that just continue without any particular logic or urgency until the pages run out, “Heat” actually has a point.)

In his extremity, the Spirit’s predicament is made even worse by his awareness of the self-absorbed people going about their daily lives, sometimes just a few feet away. Kids play ball by the mouth of the alley, taunting each other and calling names; families bicker in rooms that are just on the other side of the wall he’s helplessly slumped against; housewives gossip from window to window as they string laundry on lines suspended high above his bleeding body; traffic rumbles by on a street that he can hear but can’t reach; and all the time, as the day goes on, the voice of the radio drifts out of a nearby apartment, detailing the progressive, inexorable rise in temperature on what will be a day of record breaking heat.

Every effort the Spirit makes to do something is futile; when you can’t even stand up, doing anything heroic is out of the question. At one point he does manage to agonizingly pull himself up to a window that’s just over where he’s lying behind some garbage cans, but the woman in the room is looking the other way. By the time she turns around, the Spirit has expended all of his energy and has collapsed back to the ground. His impotent cries for help are drowned out by the noise of a vacuum cleaner.

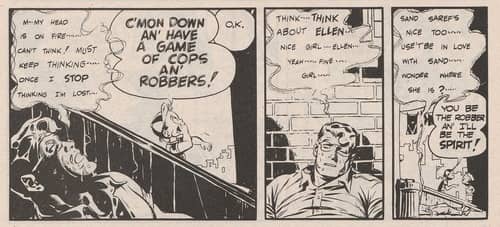

Delirious and bathed in sweat, he’s finally discovered by two little boys who run into the alley — during a game of cops and robbers. (“You be the robber ‘an I’ll be the Spirit!” one boy tells the other. He probably imagined his hero in a very different situation than the one in which he encounters him a few minutes later. Children — and not just children — prefer their fantasy figures to be the actors instead of the acted upon.)

In the last panel, with the Spirit in the hospital and the heat wave broken, the kids of the neighborhood continue with their games as the sun sets and mothers call their families in for supper. The ordinary, everyday things that most concern people go on as they ever will, with the clashes of criminal and crimefighter causing barely a ripple in the greater life of the city. People will always have more pressing things to worry about.

All this was done in seven pages. Seven pages! (And this is counting the full-page splash page that Eisner almost always began a story with.) Aside from the ambition, maturity, humanity, and graphic brilliance that leap from the panels, the thing that always strikes me most powerfully about Eisner’s Spirit stories is their narrative efficiency, their ruthless economy. Nothing is wasted. There’s not a moment of self-indulgence or an ounce of fat in a Spirit story; Eisner didn’t have the room.

This alone puts his work far ahead of most comics of his or any era. In 2006, I bought and read every twenty four page weekly issue of DC’s big event comic of that year, 52. One thousand, two hundred, and forty eight pages. I can’t remember a single thing that happened in them, unless it’s Black Adam ripping Terra-Man in two. (Was that in 52? Or did it happen somewhere else?) Lots of talented artists and writers worked on 52, but they had all the room in the world to be slack and flabby, so all too often that’s what they were.

On the other hand, I first read “Heat” in 1974, in the wonderful Spirit reprint magazine that Warren published and that introduced the character and his creator to so many younger readers. It burned its way into my mind the instant I read it, never to be forgotten. There was nothing like it on the newsstands even then; there’s damn little like it in the comic book shops even now. Most comic creators have yet to catch up with Will Eisner. (Batmarines and suspended-animation rockets — and Black Adam eviscerating Terra-Man — are contextless absurdities that don’t mean anything even if you remember them, because they’re detached from any reality that anyone could ever possibly encounter… unlike dying in a forgotten corner of an indifferent city, unseen by people who are too busy to notice.)

The difference between the Batman and Superman stories and the Spirit story are so enormous and so obvious as to need no belaboring; it’s like comparing a mildly talented middle schooler’s first try at concocting a comic book with the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Clearly, Will Eisner was playing a completely different game than his contemporaries, so different that no story even remotely like his would appear in a mainstream comic book for another twenty-five years or more.

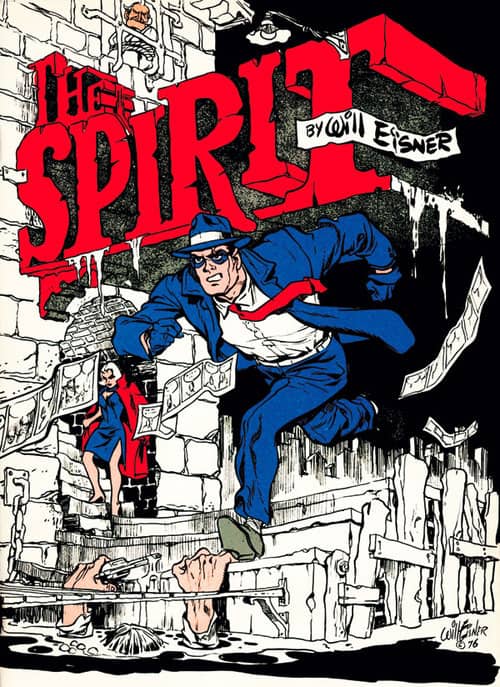

There’s a reason comics’ highest award is named after this man — artist, writer, pioneer in the use of the comic medium for education, one of the originators of the true “graphic novel” format, visionary independent and entrepreneur (unlike so many other greats of his era — Jack Kirby comes to mind — he never had to accept a demeaning deal from a publisher or negotiate for the return of his original art, because almost from the beginning, Eisner owned his creations and had full control over them), and last but far from least, creator of the most sophisticated and adult of all costumed crimefighters, the Spirit. His seventy-year-old work is still as fresh as the day the ink dried, and continues to entertain, engage, and move readers who have long left childhood and adolescence behind.

That’s because Will Eisner was ahead of his time.

Our previous coverage of The Spirit includes:

Two-Fisted Justice in an Abandoned Cemetery: Will Esiner’s The Spirit

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of Zone One by Colson Whitehead.

Obviously I see The Spirit and Will Eisner pop up everywhere.

I’m not a huge fan of detective stories or noir type stuff. But your overview has me interested enough to try it.

It just so happens my local library has a copy of Vol. 1 of the DC archives they put out around 2000.

The Archive volumes are nice, Glen, but Eisner really hit his stride with the Spirit after the war. The early stuff isn’t his strongest. (For a while, the Spirit had a flying car, because masked crimefighters had goofy vehicles, right? Then it was like Eisner said to himself, “Gee – this is stupid!”) There’s a “Best of the Spirit” trade paperback that’s quite good.

Thomas,

I just re-read your comment to my original article on THE SPIRIT back in 2014 (link above). This article is a great expansion to the points you made four years ago. I’m glad you took the time to do it.