Chasing The Immortal

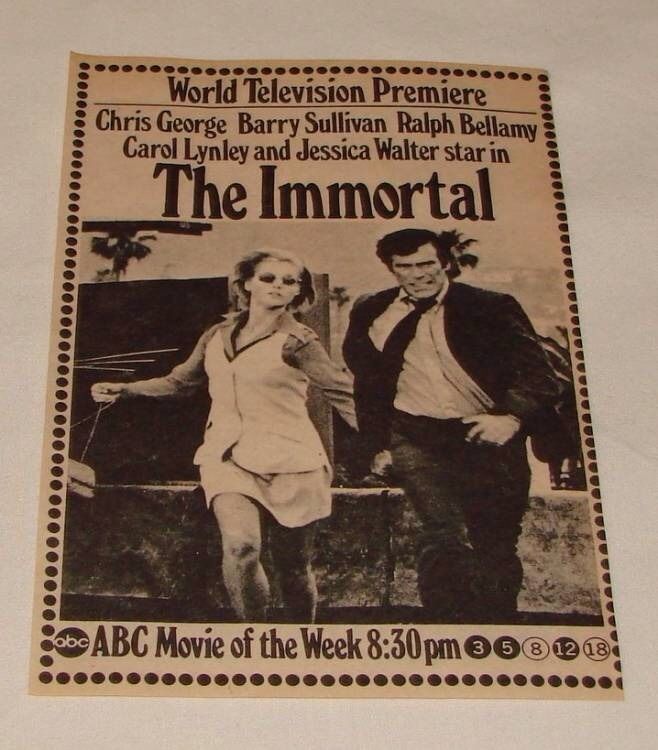

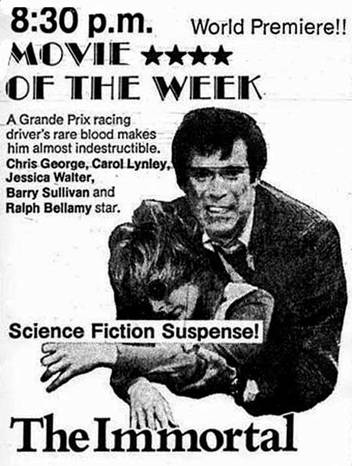

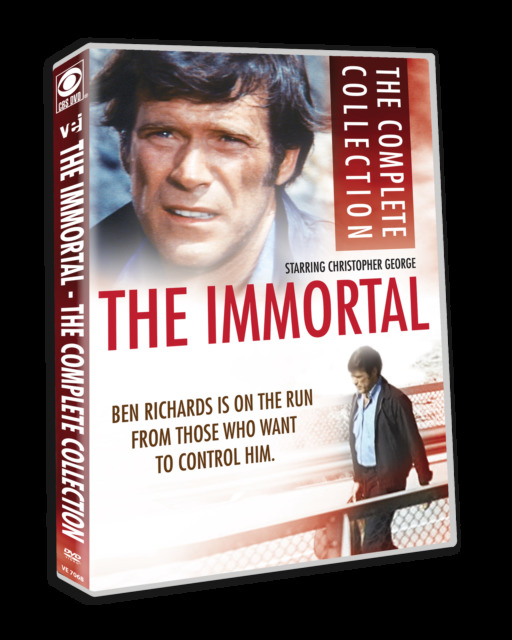

The Immortal (1970)

ABC Television

TV Movie and 15 episodes, based on The Immortals by James Gunn.

John Wayne’s real name was Marion Morrison. I know this because my father told me. Along with a hundred other small stories he told me while we watched television together. Whatever was on the screen would almost always prompt him to tell me something about the cast or the production or even, rarely and more precious because of it, what the particular story meant to him.

He often ended the little tale with a question as to what my five or seven or ten year old self thought about it. We did not interact like that anywhere else in our lives; two solitudes meeting in the one place we shared. So whatever was on the screen at the time filled the silences between my questions and his tales.

I believe I was prompted to track down The Immortal, at the risk of being maudlin, by moving my father who is suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s from our family home to a care facility permanently. In times like these mortal thoughts rise from your subconscious like Grendel from his cave. Sometimes you do things and you don’t really know why at the time. Nostalgia can find you paying for things on a whim, and in this Amazon is a ready enabler.

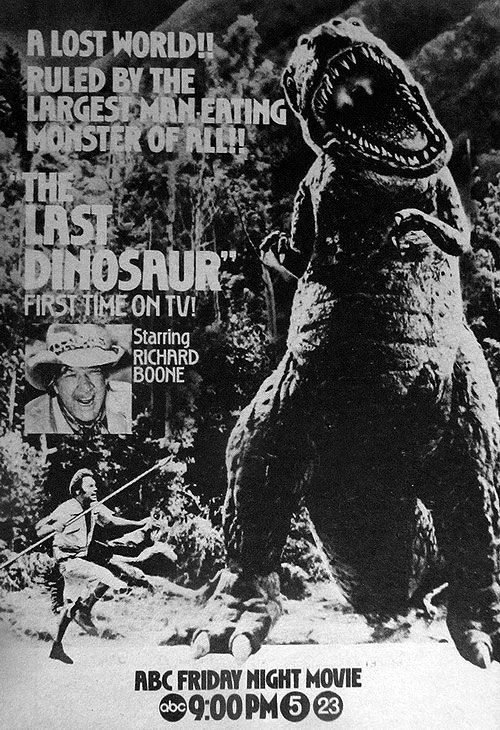

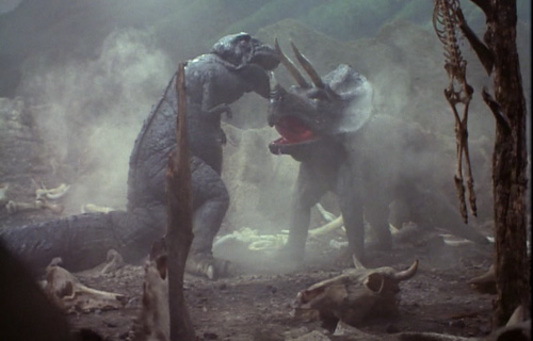

I first became aware of the 1970 ABC Network TV movie called The Immortal and its subsequent spin off series 41 years ago on a Friday night in February 1977. ABC ran a movie called The Last Dinosaur. I was cautiously intrigued by the title. I reserved my full-on excitement until I got a closer look. I had been fooled before by the One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing debacle. A “comedy” starring a “brontosaurus” skeleton, which by dint of being both a vegetarian and you know — a skeleton — didn’t end up devouring so much as a single person in that film.

Anyway… February, 1977 — I cajoled my parents into letting me watch The Last Dinosaur even though it aired at my bed-time. My father, uncharacteristically for him, pushed back against my mother when she made to enforce the rule, and he even made my siblings go to bed so I could watch it without distractions. He didn’t understand much about me — a bookish kid with a passion for extinct animals with unpronounceable names — but he knew it was important.

The Last Dinosaur featured a very post-Have Gun, Will Travel Richard Boone, the broken capillaries on his pock-marked and seamed face a paean to dissolution that would shame the painting of Dorian Gray. It had a drilling machine and an utterly unconvincing T-Rex stomping around in an underground jungle. I was seven; of course I loved it.

I refused to leave the screen for all 92 minutes. When the advertisement for a re-run of the TV movie The Immortal was broadcast during a break in the action, I was there and I remembered it. A seed was planted about this mysterious show with the most compelling title. Until last week I had never actually seen it. Before the advent of the internet, tracking down old television shows, songs by one hit wonders, regional cartoons or worse foreign productions of anything was incredibly difficult. Like the half-remembered TV movies that would haunt me BG (before Google), I forgot it. Later on in my life, every so often, it would stand out, appearing in an article or conversation here and there, or, finally as part of an utterly ironic obituary. It flickered dimly in the vaults of memory. It was something to explore at a later date maybe, if I had the time. But still intrigued about this television show that existed as only a title in my mind, a title that bluntly announced that it was telling a story of one of THE most compelling and enduring (if that word is not too much on-point) tropes in fiction.

The Last Dinosaur (1977)

It was a thought that led to my phone, which led to Amazon, which led to the series and the paperback it was based on showing up at my door by the weekend. I watched it over a weekend in the late night and over the next few days by myself.

The Immortal holds two ideas within its wonderfully stark title. It evokes both loneliness and power with nothing more than two simple words. The show itself is lonely and simple; visually without flourish and almost constitutionally averse to exploring the trope within its title. Immortality as it is played out in the series is likely the least compelling part of it as entertainment. The second idea — the individual represented by the word “the,” is somewhat more satisfying.

Any person of my age will immediately feel a sense of familiarity in the visuals of The Immortal. There is a particular washed-out ochre to the landscapes of California — It doesn’t matter whether you are hitchhiking in search for a cure to your green inner rage monster, fighting a bionic Bigfoot or wrestling a Gorn; the rocks never lie. The landscape pervades television of that era. There are other subtleties; automobile chases that kick up fountains of reddish dust, tall shaggy-barked conifers rising off camera into clear blue skies and the pervasive sunniness that has actors in outdoor scenes perpetually squinting. If the interiors of that era were Norman Lear the exteriors were pure Hollywood backlot. It never rains in California it seems — except in LA at night. I have since found myself in the southwest multiple times in my life. I’ve driven through Death Valley, walked the High Sierras, stood at the edge of Area 51 and lay on top of a car hood in the high plateaus in Arizona and drank in the sight of more stars that I knew existed. It is odd to be so familiar with the landscape of a place you have never been, but my first experience there filled me with an aching familiarity.

The concept of the show is a simple one, Benj Richardson, test driver for Braddock Industries has blood that can be universally transfused and also makes him immune to all known diseases including old age. Transfusions of his blood can temporarily stave off death, grant remission of disease, put off senescence, and speed healing from even fatal injuries.

Benj, played by Christopher George, discovers this when a pint of his innocently donated blood saves the life of his boss, the aged and feeble multimillionaire Jordan Braddock (Barry Sullivan in terrible age make-up).

While the blood makes Braddock a newer and younger man, the vitalizing effect is only temporary. Braddock, realizing that his lifeline is test driving glorious Detroit metal for a rather dangerous living, decides to protect his investment. He has Richardson kidnapped and sequestered in a luxury bomb shelter under guard as a sort of human juice box of youth.

And it is in the bomb shelter that Benj Richardson stays forever and ever; engaging in progressively more demented monologues with himself; the visuals become rife with Felliniesque beats and affectations; including breaking the fourth wall to directly engage an unresponsive audience in the futility of the human condition. More and more of the series is shot through the frame of a stage mirror, Christopher George’s face harshly lit, covered in increasingly more deranged grease paint; his lines delivered while striking mad poses until it ends with him immobile in a single spotlight in an otherwise pitch black room while the score from Pagliacci plays in an endless loop.

The End.

Okay. I lied.

Benj escapes with the help of Braddock’s wife, a bikini clad and lissome Jessica Walter, hungry for her inheritance and nonplussed at the idea of her elderly husband living any longer than necessary. Ben sets off to find his missing brother Jason, separated from Benj as a child when their parents were killed. Jason may or may not have the same gift Benj has. The word gets out about Benj to other rich men with an interest on living forever. He breaks with his fiancée to keep her from harm and goes on the run. The decrepit Braddock is replaced in the series by another apex capitalist suffering from a similarly undefined illness, Arthur Maitland. And Maitland is served by one Mr. D. Fletcher; ginger, British and coldly driven to capture the hero. Queue the plot for every single episode. Benj is on the run. Benj is tracked by an obsessed Javert (or Inspector Gerard, or Jack McGee) who serves “the powers that be” in order to exploit our hero for some goal — stop me if this seems a bit familiar.

Grab a screenshot of The Immortal; any screenshot from any episode and you will have the content of the series played out for you. You could substitute a shot of Bill Bixby from The Incredible Hulk half a decade later and it would fit. The program is exactly what it appears to be and nothing more. It is straightforward American escapist television with that curious muting of any emotional, philosophical or intellectual highs or lows. That middle road that is a characteristic of even high concept television programming from that era. Watching it I was repeatedly struck with how the story ran exactly like how I imagined the pitch to the studio might have gone.

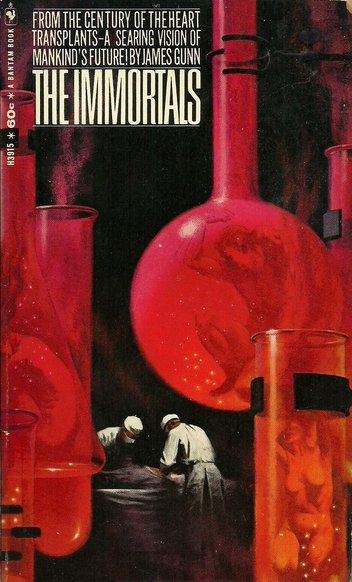

The original book that this was based on, Hugo Award winning and Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America 24th Grand Master, James Gunn’s The Immortals plural — had a vagrant with the magic blood. That would almost certainly have been far more interesting in terms of possible plot considerations but ultimately would have likely made it unsaleable for network television at the time. The lead in the book isn’t just sought for his blood, but also his organs. The threat was more (literally) visceral, and far too sanguine an idea to consider for television at the time.

The Immortals, by James Gunn

Benj Richardson test driver was appropriate. Magic blood was appropriate. Like Cyborg, the novel that inspired The Six Million Dollar Man or even The Incredible Hulk comic book, the source material had room to explain the concept than an episodic series at the time was willing or capable of examining. That was a limitation of the time. When Marshall McLuhan said the media is the message, he was right. How we consume media will ultimately shape the media that we consume. You can binge watch programming now. Television has room to run stories over multiple episodes. In the 1970’s TV only allowed that kind of decompression in soap operas which were shown daily to housebound women. In the 1960’s and 70’s network nighttime programming moved in formulae.

The formula in The Immortal was not actually about immortality. The main theme represented in the series is what I call “The Lonely Man.” The individual protagonist is on the run. It could be Richard Kimble in The Fugitive. It was also David Banner in The Incredible Hulk. Each series marked by a common visual palette of a lone man walking a highway seeking something. A deeper view might read a kind of examination and era specific definition of masculinity. The protagonist is uncertain, driven, wrestling with the nature of what it is to be a man in the America of the time. The opponent is the system. They are representatives of a justice system without mercy, the tabloid press who must get the story, without mercy or in The Immortal, the rich who wish to keep on living and will do what they need to do, once again, without mercy.

To sell it the lead was changed to a familiar character. The 1970’s hero. Athletic and good looking, possessing enough hair to show under the collar of an unbuttoned shirt, but not so much that it gave him gorilla arms. He is not rich but not poor, smart — but in a practical sense and he has something that sets him apart. David Banner was a scientist but like Richard Kimble was also a medical doctor, Benj Richardson, test driver and mechanic. Although not part of the lonely man club, Steve Austin, test pilot and astronaut would fit the mold. These were men who had practical intelligence. They met the social ills of their day not with contempt but with compassion and better, they were actually useful. And not just because of preternatural power — but because when something went wrong they had the confidence and ability to try and fix it. They were men who couldn’t but help when needed.

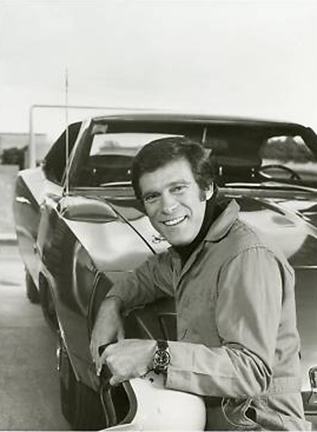

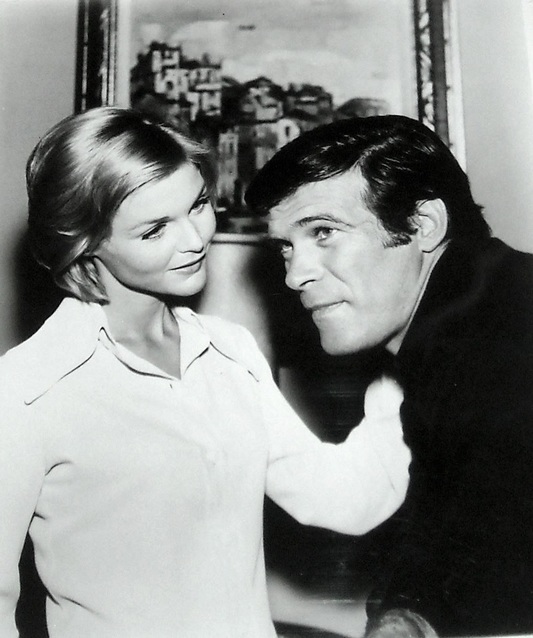

They could not have chosen a better man for the role than Christopher George, fresh off of TV series The Rat Patrol. George was an exemplar of the American men who were born in the very late 30’s or 40’s and who came to age in the 1950’s. He was the son of immigrants. As a kid in Jacksonville, he made money hunting Alligators. Inspired by John Wayne, he lied about his age to enlist in the Marines at 16. He was a test pilot, served in Korea as a medic. He had actual black belts in both kinds of music — Country and Western… I mean karate and judo.

He eventually drifted from the service into acting and made movies with Wayne, Chisum (1970) being the most memorable. He was handsome, but not overwhelmingly so and if his range as an actor wasn’t on best display in the series, he was charming, sympathetic and projected an honest strength. George married the woman he loved and never left her. He was what John Wayne seemed to be. He was what my father’s generation would have respected. An achiever with a sense of duty. His portrayal of Benj Richardson embodies the idea of the useful man. Fully half of the episodes have him fixing a car or truck or motorcycle. That ability ends up being far more helpful than not being able to die.

The formula of choice for The Immortal is what used to be called episodic television. Each episode of the program followed the same basic plan. All episodes were minor variations on that theme. Prime examples would be anything with a stalwart leading man facing a crisis with a feather-light look at social issues thrown in to make it topical, the presence of guest stars and a plot that is resolved in under 45 minutes and always brought the character back to the status quo. Episodic programming would frequently be a recap episode, cut together from bits of the pilot and other episodes frequently as part of the formula. If the issue addressed in the episode was a really big deal — you might get a two-parter and have to wait until next week to get the hero back on track. If you were very lucky the series ended before the lead actor or actress decided to cut an album and have their warblings become part of the show.

I’m sounding cynical, but as a child I wouldn’t have missed either the second Bigfoot episode or the Venus space probe terror facing Steve Austin if it cost me an actual non-bionics arm. There is a recap episode in The Immortal. There is also one two-parter in the series; it is in the last two episodes before its early cancellation. Once again, this seems to be a bit on the nose for a series about limitless lifespan.

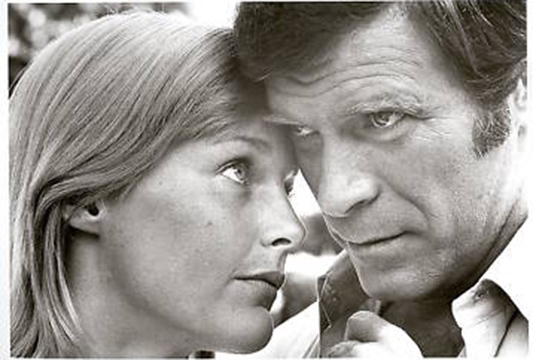

Christopher George and Carol Lynley in The Immortal

Immortality on television up to the time of The Immortal followed the tradition established in the pulps and comics and literature right back to Plutarch’s Lives. Namely that unlimited life is the sole purview of the gods. For a human to become immortal was very much an offense against the sacred. Thus immortals were Wandering Jews or biblical fratricides, vampires or unholy sorcerers who made a pact with unholier entities. God is immortal. Man is not. Immortal mortals is not only an oxymoron, but also an upending of universal law. The alternative to being an abomination of the cosmic order wasn’t much better for a character. If you weren’t the enemy of God you were doomed to die of boredom. The character of Mr. Flint in the classic Star Trek episode “Requiem for Methuselah” was Caesar and Da Vinci and lived lifetimes of incredible achievement before ending up the victim of ennui with a sex-bot out beyond the limits of Federation space.

The Immortal as a series does not delve into any complexities or examine existential concerns. Immortality is nothing more than the hook to drive the story. Benj Richardson is not thousands of years old. He’s 42 and he looks 30 (sort of). Benj does not have a Juan Sánchez Villa-Lobos Ramírez to provide exposition and teach him swordplay and the rules. He is not part of a coven of re-souled blood drinkers that allows for the costume department and location scouts to go hog-wild. Benj Richardson is just a man with a condition that forces the series into action. Any examination of the condition in the narrative only to serve to get him from one fairly well choreographed fight scene to another, one middling to fair automobile chase to the next; one oddly similar waifish blonde romantic interest to the next.

I once read somewhere that there are only five different themes underneath the trappings of any story. Protagonist versus nature, rock versus scissors, scissors versus paper… something like that… I think it’s much simpler. There is only ultimately, one story; the protagonist versus death. I place a proviso that “versus death” doesn’t necessarily mean a Michael Bay remake of The Seventh Seal complete with hyperkinetic gunfight instead of a chess game. There is enough gravity in the word immortal to spawn ten Wikipedia lists relating to it. A protagonist who will, barring any accidental violent incidents, practically live forever has a myriad of possibilities. A quick look at the landscape of popular fiction now shows so many flavours of the theme reveals an almost pathetic fantasy that appeals to human beings on a basic level. It’s almost like people don’t want to die.

Immortality as conceived by mortal creatures is difficult and perhaps better left as metaphor. All we do, all meaning, relationships, drives, passions are all brush strokes on a limited canvas. Simple stories involve peril against actual physical extinction. More complex ones wrestle with existential questions of purpose and place. One might say that all stories themselves are a denial of our mortality. Stories pass words down through time beyond the span of their actors or authors. Achilles is immortal, not for his goddess mother, but because poets still tell the tale of him. Over the years since 1970 we have been inundated by immortals. I don’t claim that the series inspired any of it; perhaps it did. If only because it failed to explore the immortality granted its protagonist in any meaningful way. Benj Richardson doesn’t give immortality a second thought. Living forever is good if people would just let me get on with it. His reason for running? “I need to be free.”

If the execution of the program is a bit simplistic then call it more a function of its time and the limitations of the medium. There are, after all, many small and crude pyramids built in Egypt before the ones assembled at Giza. The Immortal contains seminal ideas that have expanded and been opened for greater exploration in better told tales told later on. Perhaps the greatest gift of speculative fiction beyond the enjoyment of a good yarn is that it allows us to examine and evolve ideas. Each entry into the canon can build from the previous idea. Given time or relevance, ideas evolve like life. It starts simply, your basic unicellular blob and then complexity spawns and given enough time and enough stressors and you get dolphins and boa constrictors, and more than that — you get behaviors like the throb of a murmuration of starlings or witch hunts on social media.

What alters the viewpoint alters the conception. The idea evolves. It increases in complexity. It becomes a gem with many facets, each illuminated by the viewer. Now we have mystic sword wielding clansman, beautiful undead and uploaded consciousnesses in biological sleeves that star in film noir redux via Netflix. The Immortal could not help but be the unicellular blob metaphorically referred to above. The Immortal fills in no gaps — rather the opposite. It leaves open spaces. It almost invites meditation on the theme if only because it doesn’t really explore it.

Is it worth watching? I think that given the modern tastes the episodic nature would be too formulaic for most viewers. I think the limited explanation and exploration of the immortality theme in the story will make it too simplistic for those who have seen the idea explored elsewhere with more depth. But If you have ever had insomnia and sat up flipping channels and felt an ineffable rightness when you lucked into a spaghetti western or re-runs of The Twilight Zone or an Original Star Trek episode; that matching of empty landscapes filled with small human dramas combined with a comfortable chair and the quiet dark, then yes, I recommend it.

More than that I can’t tell you. Right now it is too close for me; like a bottle of wine drunk at the right time. It all becomes mixed together with the quiet and my thoughts. I find myself thinking of long dusty highways that run into landscapes that remind me of the broken capillaries on the craggy face of Richard Boone. I remember that Christopher George died at 52, victim of an undiscovered cardiac injury suffered on-set of The Rat Patrol; in a brutal piece of irony. I remember a large Zenith console television and me in pajamas, my father on the couch, the opening scene of The Six Million Dollar Man which was the only time you would actually see him running in real time, superhumanly fast.

I imagine that characters in cancelled series somehow live on past the end of their final broadcast, not cancelled, but freed to seek out their ultimate destinies; Kimble and Banner, Steve Austin and Benj Richardson, meeting in a roadside diner on a dusty southwest stretch of highway. I try and recall the last story my father told me and fail. I can’t remember and as he has lost all of his words, I can’t ask him. I turn back to Benj Richardson walking alone down a long highway, the voice over narrating his condition in stark words, the California sun bleaching the landscape and asphalt; a lonely man, seeking something just beyond far horizons but always willing to set aside his problems to help those in need on his way. A story watched one more time, in the dark, persisting a bit longer, for whatever that’s worth.

I wake in the morning in the chair, the television still on. I then drive through the snow and ice to my ex-wife’s place and watch a movie with my 11 year old daughter who is recovering from some dental surgery. She is bundled in a blanket nestled in beside me. A movie plays.

I tell her that the man who made this movie was born in Canada. He is one of the few people in the world to take a submarine to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. That’s six miles deep.

She snuggles a bit closer and doesn’t say anything.

John Searle is a Canadian insomniac working his way through a Masters degree and breaking that up by watching far too much classic television and old movies. He is presently working on his first novel. He expects to have it finished within the next decade. Give or take… another decade.

That tears it. I’m watching The Man From Atlantis tonight!

Excelent article and a tribute to your father that honors the relationship in a very poignant way. For years my much desired TV series was Coronet Blue which to my amazement finally made it to DVD. It had its moments but sadly the plot-man with amnesia being chased by a mysterious group wasn’t developed as fully as it could have been. My Holy Grail TV series is one no one remembers–the Aquanauts/Malibu Run–the Keith Larsen episodes (Ron Ely replaced him and titled change to Malibu Run. back then Lloyd Bridges’ Sea Hunt owned the genre of skin diving shows..

I’ve previously explored The Last Dinosaur at Black Gate. It’s easily available through Warner Archive and holds up well as classic Lost World entertainment.

Thanks Folks. Thomas—I never quite got the Man From Atlantis. Aquaman could talk to fish. The Sub-Mariner could lift an ocean liner. Patrick Duffy swam like a dolphin and had gills. It always struck me hat he would be Duffy tartar when he ran across a fair sized shark. Allard–I have an old vhs tape of Doc Savage with Mr. Ely in it. No one ever better embodied a pulp character better–the quality of the movie aside. Also–Is it Ron Ely as in Eli Wallach? Or is it Ron Ely like something like an eel in whedonspeak? And Ryan– I’m going to read your article immediately. Thanks for the welcome.

FYI, the most recent issue of Locus has an interview with James Gunn, and he does talk about The Immortal TV show.

To John—It’s Ron Ely who also played Tarzan on a TV series late 60s and even a revival of Sea Hunt. I have only seen the Doc Savage movie once–at the theater and like the Jonah Hex film (love that comics series)have no plans to ever revisit. The Shadow holds up a bit better.

Loved this article — Never watched the show and, for the reasons you iterate, probably wouldn’t care to; But I’m glad you did, as a catalyst for the rumination here.

A wonderful piece of writing that evokes a lot of memories for me–both of this series, and watching old movies with my father. Thanks for this.