Mythic Landscape: The Weirdstone of Brisingamen by Alan Garner

Halfway through my recent reread of Alan Garner’s 1960 debut novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, it became clear to me that the true protagonist was the land, not the ostensible ones, sister and brother Susan and Colin.

Halfway through my recent reread of Alan Garner’s 1960 debut novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, it became clear to me that the true protagonist was the land, not the ostensible ones, sister and brother Susan and Colin.

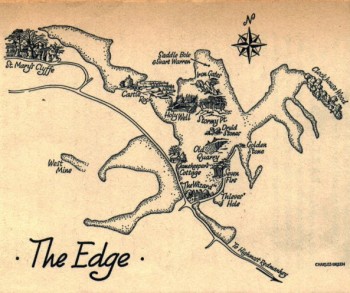

Alderley Edge, in Cheshire, England, is the name of both a village and a great sandstone cliff “six hundred feet high and three mile long.” For Garner there’s a connection between land and myth, artistically at least, that is deep. His depiction of a land of rolling plains littered with farms and woods, riddled with thousands of years’-worth of mines makes it easy to see the svart-alfar, the “maggot-breed of Ymir,” boiling out of the earth. There’s something deeper than that, though; something that reaches beyond mere physical for Garner. It’s as if the land itself bred those stories and they are intertwined with it intimately and inextricably. Just walking the woods and rises around Alderley Edge, they can be felt pushing themselves up from the earth and traveling along on the backs of breezes.

Before the story proper begins, Garner recounts a true legend of Alderley Edge — that of a farmer from the village of Mobberly and the strange white-bearded man he meets on the way to market. The farmer hopes to sell his white mare at market in Macclesfield and when he agrees to sell it to the bearded man instead, he is shown a secret cave protected by an iron gate and filled with treasures. Inside sleep 140 knights, each, save one, with a perfect white mare by his side. The wizard, for that is what he is, tells the farmer why the knights are there:

“Here they lie in enchanted sleep,” said the wizard, “until a day will come — and come it will — when England shall be in direst peril, and England’s mothers weep. Then out from the hill these must ride and, in a battle thrice lost, thrice won, upon the plain, drive the enemy into the sea.”

In payment, the wizard tells the farmer to take whatever gold and gems he can fit into his pockets. He does, with unexpected and dire consequences for the future.

While their parents travel, Colin and Susan are sent to Bess and Gowther, their mother’s old nurse and her husband, in Alderley Edge. Warned to beware the unsafe entrances to the old copper mines, they are otherwise allowed to explore the countryside around the farm. On their first day out they come across an inn called The Wizard, and their curiosity is aroused by a sign depicting “a man, dressed like a monk, with long white hair and beard: behind him a figure in old-fashioned peasant garb struggled with the reins of a white horse which was rearing on its hind legs.” They leave their questions for another time, though, and begin their trek through the Edge and among its woods:

All through the afternoon Colin and Susan roamed up and down the wooded hill-side and along the valleys of the Edge, sometimes going where only the tall beech stood, and in such places all was still. On the ground lay a thick carpet of dead leaves, nothing more: no grass or bracken grew; winter seemed to linger there among the grey, green beeches. When the children came out of such a wood it was like coming into a beautiful garden from a musty cellar.

It’s a splendid day until only a few hundred yards from home, Colin and Susan are accosted by a strange woman who tries to get them into her car. She begins to say things in Latin that make Colin sweat and feel like “all awareness” was leaving his body, but drives off when Gowther and his dog approach. It turns out the woman is Selina Place, a local landowner.

It’s a splendid day until only a few hundred yards from home, Colin and Susan are accosted by a strange woman who tries to get them into her car. She begins to say things in Latin that make Colin sweat and feel like “all awareness” was leaving his body, but drives off when Gowther and his dog approach. It turns out the woman is Selina Place, a local landowner.

For Susan, the most puzzling part of the encounter is what happens to her Tear, the jewel that hangs from a bracelet her mother gave her. All day, it had sparkled in the sun, but when Selina Place began speaking to them, it clouded up. Later, she learns from Bess that while she gave it to Susan’s mother, her family had owned the Tear for ages.

The next day, while again exploring the Edge, Colin and Susan are attacked:

Colin and Susan moved forward slowly, longing to run, but somehow held by the crow’s wicked eye. And as they reached the centre of the dell the bird gave a loud, sharp croak. Immediately a shrill cry answered from among the rocks, and out of the shadows on either side of the children rose a score of outlandish figures.

They stood about three feet high and were man-shaped, with thin, wiry bodies and limbs, and broad, flat feet and hands. Their heads were large, having pointed ears, round saucer eyes, and gaping mouths which showed needle-sharp teeth. Some had pug-noses, others long, thin snouts reaching to their chins. Their hides were generally of a fish-white colour, though some were black, and all were practically hairless. Some held coils of thin, black rope, while out of one of the caves advanced a group carrying a net woven in the shape of a spider’s web.

After a long chase through woods and mire Susan and Colin are captured. Only then, when all hope is lost, they are saved by the sudden appearance of a man, “taller than any they had ever known,” and wearing a long white robe, carrying a white staff, and with a long, white beard. With a flash of blue-white light from his staff, he drives off the creatures. He quickly leads the siblings to safety in a cave; the same iron-gated one from the legend.

After a long chase through woods and mire Susan and Colin are captured. Only then, when all hope is lost, they are saved by the sudden appearance of a man, “taller than any they had ever known,” and wearing a long white robe, carrying a white staff, and with a long, white beard. With a flash of blue-white light from his staff, he drives off the creatures. He quickly leads the siblings to safety in a cave; the same iron-gated one from the legend.

The wizard is Cadellin and he is sworn to protect the sleeping knights until they are needed. Unfortunately, their well-being is in danger: the linchpin of the magical defenses that allow them to remain ageless, the gem Firefrost, is missing. Cadellin visits the cave only rarely, and it was a century ago that he realized Firefrost was lost. His effort to track down the descendants of the farmer from Mobberly — for only he could have taken it — proved fruitless. Even more distressing, Cadellin’s actions alerted the forces of darkness, among them the svart-alfar — the creatures that attacked the children — and Selina Place, in reality the Morrigan, a powerful witch.

Obviously, Susan’s Tear is the lost stone, but neither she nor Colin makes the connection between it and Cadellin’s account. The wizard doesn’t notice it as it’s tucked up and hidden by Susan’s sleeve. It’s one disappointing moment in an otherwise excellent book.

The rest of the story involves the Tear falling into the hands of the knights’ enemies, its recovery, and an epic journey under the surface of Cheshire. That journey is followed by a trek across fields and forests, the children and Gowther guided and guarded by two dwarf warriors, in search of Cadellin.

It is during the children’s subterranean adventure that The Weirdstone of Brisingamen comes into focus. It is exciting, reeking of claustrophobia and fear. Constantly on the watch for svarts, wary of chasms suddenly appearing, Susan and Colin become hopelessly lost. The children, not particularly developed beforehand, begin to take on semblances of personalities. Colin becomes more and more fretful as time passes, while Susan emerges as someone with more courage and tenacity than anyone expected. The surprise arrival of two dwarfs, Durathror and Fenodyree, friends of Calledin, saves them, though not without bloody run-ins with hordes of svarts and passage through more, and more, dangerous tunnels.

It is during the children’s subterranean adventure that The Weirdstone of Brisingamen comes into focus. It is exciting, reeking of claustrophobia and fear. Constantly on the watch for svarts, wary of chasms suddenly appearing, Susan and Colin become hopelessly lost. The children, not particularly developed beforehand, begin to take on semblances of personalities. Colin becomes more and more fretful as time passes, while Susan emerges as someone with more courage and tenacity than anyone expected. The surprise arrival of two dwarfs, Durathror and Fenodyree, friends of Calledin, saves them, though not without bloody run-ins with hordes of svarts and passage through more, and more, dangerous tunnels.

Of the book’s 21 short chapters, the voyage in darkness comprises 5 of them. In them, Garner brings the sub-surface world to life. His love for the land starts to become apparent in his detailed descriptions of this place of secret beauty and danger; another world, hidden just below the farms and villages of Cheshire.

Susan and Colin’s hunt for Cadellin lacks the claustrophobia of their previous undertaking, but it is equally frightful. They are beset by neighbors secretly in service to the powers of evil, giant crows, and even trolls. Old myths, just as the legend of the sleeping knights, prove real as they cross from farm to woods to hillside. Atop a stone outcrop, a river-dwelling stormkarl sings a prophecy of the battles to come. The elves, the lios-alfar, long having fled from the killing-blight of industrialization and pollution, appear to have returned, and a mystical island appears out of nowhere in a simple, country lake.

At some point, Garner himself called it “a fairly bad book” and technically inept. I won’t argue with him too much. None of the characters are especially well characterized. The children, never fazed by any of the wild, supernatural events, don’t come across as believable much of the time. Often they are unaware of what’s going on around them, and are bit players in the important events transpiring. The ending, impressive though it is, is abrupt.

Still, I find The Weirdstone of Brisingamen a beautiful, poetic story. Despite some thrilling moments, its success doesn’t lie with its diffuse plot, but with Garner’s recreation of Alderley Edge as a living, breathing place where the unreal lies just out of sight. He almost makes you believe the supernatural has always been there in the dells and copses around Alderley Edge, hidden, just waiting for the right moment to be exposed.

Garner’s later books dig more deeply into the intersection between the land and myth than this one, but the idea is fresh here, as if it’s something just being uncovered. Imperfect as it is, TWoB has held up well over the past six decades.

In 1963, Garner wrote a sequel, The Moon of Gomrath. It returns Susan and Colin to Alderley Edge for an even more dangerous encounter with the supernatural. It was not until 2012 that he wrote a final volume, Boneland. I haven’t read it, but looking at reviews, it appears to be aimed at adults, not children. Matthew David Surridge wrote about Weirdstone and Moon here at Black Gate in 2012.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now.

Another one of those series that’s been sitting neglected on my shelf for a couple of decades. Someday …

The Weirdstone is a topographic romance. See the discussion here, with a note of the Ordnance Survey map to use when reading the book.

http://fancyclopedia.org/topographic-romance

@Joe H – Dont’ worry, they’re so damn short, you could read them both in a day when you finally get around to it (but you should 😉 )

@Major W. – thanks, that’s a great piece. I used Ordnance maps during an aborted walking tour of Dartmoor a few years ago. They’re amazing and I’d love to see the one for Alderley Edge.

I remember reading ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ as a kid – an old blue hardback, sans the cover – in a relative’s house. I thought it owed a pretty big debt to Tolkien even then. I felt the same about a book which I read much more recently – ‘Elidor’. A later book ‘Red Shift’ is much more experimental, tonally and structurally, and (although it might not be to everybody’s taste) I reckon it shows Garner really finding his voice.

I read The Weirdstone and Gomrath as a child, back in the sixties and I loved them. Reading his fourth novel, The Owl Service, was memorable for me because it was so bloody difficult! Almost entirely cast in dialogue and based on a Welsh legend which, in itself, was confusing. I recall feeling triumphant, when I got through the book because it had made me work and work hard. I have read as much Garner as I could, ever since and followed his path from derivative fantasy author to major novelist. Boneland will disappoint many people because it is nothing like Weirdstone or Gomrath but I found it a very satisfying novel. Ursula Le Guin wrote a very good review, which can be found here https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/aug/29/boneland-alan-garner-review. The novel is suffused with the landscape and mythology of his native Cheshire and brings a very grown up perspective to the events of the first two novels. To my mind, Garner is a genius who is most concerned with the past and place. Neilh