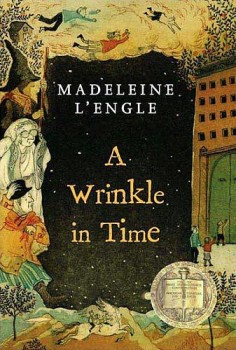

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeline L’Engle

Given to me by the same friend who told me about A Wizard of Earthsea, Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (1962) is another of the books that introduced me to fantasy and science fiction. The novel is a mix of science fiction, fantasy, and good dose of Christianity, and is completely unbound by any rules or expectations about genre. A children’s book, it is also an artifact of a time when fantasy wasn’t primarily a commercial designation. There’s a freshness to the book all these years later, and rereading it was an absolute joy.

Given to me by the same friend who told me about A Wizard of Earthsea, Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (1962) is another of the books that introduced me to fantasy and science fiction. The novel is a mix of science fiction, fantasy, and good dose of Christianity, and is completely unbound by any rules or expectations about genre. A children’s book, it is also an artifact of a time when fantasy wasn’t primarily a commercial designation. There’s a freshness to the book all these years later, and rereading it was an absolute joy.

Meg Murry is the fourteen-year-old daughter of scientists, and sister to twins Sandy and Denys and the strange, brilliant five-year-old Charles Wallace. Her father, employed by the government, has been missing for some time before the book’s opening, and there has been no word about what happened to him.

In her own eyes Meg is gawky and ugly, made so by her “mouse-brown” hair, glasses, and “teeth covered with braces.” Her self-impression and her worry over her father’s disappearance have caused her to become a poor student. Her principal, a man unsympathetic to her worry to the point of telling her she needs to “face the facts” about her father (implying he’s never returning), warns her she’s in danger of having to repeat ninth grade.

Only her little brother is able to calm her down. Commonly thought to be disabled by most people outside his family because he rarely speaks, Charles Wallace is, in reality, a prodigy. Beyond a preternatural grasp of math and science, he also seems to be able to, if not actually read his family’s minds, know what they’re feeling at any given moment.

Only her little brother is able to calm her down. Commonly thought to be disabled by most people outside his family because he rarely speaks, Charles Wallace is, in reality, a prodigy. Beyond a preternatural grasp of math and science, he also seems to be able to, if not actually read his family’s minds, know what they’re feeling at any given moment.

When Meg, Charles, and their mother have an impromptu kitchen gathering one night during a hurricane, they are visited by a strange figure who goes by the name of Mrs. Whatsit:

After a few moments that seemed like forever to Meg, Mrs. Murry came back in, holding the door open for — was it the tramp? It seemed small for Meg’s idea of a tramp. The age or sex was impossible to tell, for it was completely bundled up in clothes. Several scarves of assorted colors were tied about the head, and a man’s felt hat perched atop. A shocking-pink stole was knotted about a rough overcoat, and black rubber boots covered the feet.

“Mrs Whatsit,” Charles said suspiciously, “what are you doing here? And at this time of night, too?”

“Now, don’t you be worried, my honey.” A voice emerged from among turned-up coat collar, stole, scarves, and hat, a voice like an unoiled gate, but somehow not unpleasant.“Mrs — uh — Whatsit — says she lost her way,” Mrs. Murry said. “Would you care for some hot chocolate, Mrs Whatsit?”

The arrival of Mrs. Whatsit sets off what will ultimately become Meg and her brother’s quest to rescue their father from an unimagined evil. Joined by a boy from her school, Calvin O’Keefe, and two more strange women, Mrs. Who and Mrs. Which, it’s a trip that will take them across the galaxy, through dimensions and time, to several different planets, and to meet alien beings, some wonderful, some dangerous. There are moments of compelling beauty as well as darkly subtle terror:

The arrival of Mrs. Whatsit sets off what will ultimately become Meg and her brother’s quest to rescue their father from an unimagined evil. Joined by a boy from her school, Calvin O’Keefe, and two more strange women, Mrs. Who and Mrs. Which, it’s a trip that will take them across the galaxy, through dimensions and time, to several different planets, and to meet alien beings, some wonderful, some dangerous. There are moments of compelling beauty as well as darkly subtle terror:

Below them the town was laid out in harsh angular patterns. The houses in the outskirts were all exactly alike, small square boxes painted gray. Each had a small, rectangular plot of lawn in front, with a straight line of dull-looking flowers edging the path to the door. Meg had a feeling that if she could count the flowers there would be exactly the same number for each house. In front of all the houses children were playing. Some were skipping rope, some were bouncing balls. Meg felt vaguely that something was wrong with their play. It seemed exactly like children playing around any housing development at home, and yet there was something different about it. She looked at Calvin, and saw that he, too, was puzzled.

“Look!” Charles Wallace said suddenly. “They’re skipping and bouncing in rhythm! Everyone’s doing it at exactly the same moment.”

This was so. As the skipping rope hit the pavement, so did the ball. As the rope curved over the head of the jumping child, the child with the ball caught the ball. Down came the ropes. Down came the balls. Over and over again. Up. Down. All in rhythm. All identical. Like the houses. Like the paths. Like the flowers.

Then the doors of all the houses opened simultaneously, and out came women like a row of paper dolls. The print of their dresses was different, but they all gave the appearance of being the same. Each woman stood on the steps of her house. Each clapped. Each child with the ball caught the ball. Each child with the skipping rope folded the rope. Each child turned and walked into the house. The doors clicked shut behind them.

Unlike the previous children’s books I’ve reviewed here — Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three and Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea — A Wrinkle In Time feels like a work of spontaneous generation. Both Alexander and Le Guin, who were already writing fantastic fiction, are on record as stating they deliberately set out to write books about certain things they wanted to say to younger readers. L’Engle’s first fantasy book reads like it sprang not from any plan, but from images and impressions that grew and matured into a full story. According to Wikipedia, the first idea that led ultimately to A Wrinkle in Time was the sudden appearance of the names Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which.

Unlike the previous children’s books I’ve reviewed here — Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three and Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea — A Wrinkle In Time feels like a work of spontaneous generation. Both Alexander and Le Guin, who were already writing fantastic fiction, are on record as stating they deliberately set out to write books about certain things they wanted to say to younger readers. L’Engle’s first fantasy book reads like it sprang not from any plan, but from images and impressions that grew and matured into a full story. According to Wikipedia, the first idea that led ultimately to A Wrinkle in Time was the sudden appearance of the names Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which.

Alexander and Le Guin were largely concerned with young men learning about responsibility and the obligations attendant to it. L’Engle writes about evil and its temptations. Evil, in the book, is a tangible thing that clouds planets from sight and suffocates their inhabitants, turning them into almost mindless automatons. Meg and her companions are first given a view of it when they are on the planet Uriel:

“That sort of shadow out there,” Calvin gestured. “What is it? I don’t like it.”

“Watch,” Mrs Whatsit commanded.

It was a shadow, nothing but a shadow. It was not even as tangible as a cloud. Was it cast by something? Or was it a Thing in itself?

The sky darkened. The gold left the light and they were surrounded by blue, blue deepening until where there had been nothing but the evening sky there was now a faint pulse of star, and then another and another and another. There were more stars than Meg had ever seen before.

“The atmosphere is so thin here,” Mrs Whatsit said as though in answer to her unasked question, “that it does not obscure your vision as it would at home. Now look. Look straight ahead.”

Meg looked. The dark shadow was still there. It had not lessened or dispersed with the coming of night. And where the shadow was, the stars were not visible.

What could there be about a shadow that was so terrible that she knew that there had never been before or ever would be again anything that would chill her with a fear that was beyond shuddering, beyond crying or screaming, beyond the possibility of comfort?

Meg’s hand holding the blossoms slowly dropped and it seemed as though a knife gashed through her lungs. She gasped, but there was no air for her to breathe. Darkness glazed her eyes and mind, but as she started to fall into unconsciousness her head dropped down into the flowers, which she was still clutching; and as she inhaled the fragrance of their purity her mind and body revived, and she sat up again.

The shadow was still there, dark and dreadful.

I know for a fact that I haven’t read this book since 1995, but my memories of it remained sharp and wonderful. Charles Wallace, supernaturally gifted and wise, is a fun character. L’Engle’s real achievement, though, is with Meg. She’s every unsure adolescent. She sees herself as ugly compared to her mother, unpopular next to Sandy and Denys, and dumber than Charles Wallace. Suddenly, she’s thrown into a deadly adventure and must force herself to face terrible fears and seemingly insurmountable odds. Alexander and Le Guin wrote about learning responsibility, obviously a valuable lesson. L’Engle wrote about overcoming hopelessness. Maybe even more than responsibility, that’s a lesson worth learning right now.

I know for a fact that I haven’t read this book since 1995, but my memories of it remained sharp and wonderful. Charles Wallace, supernaturally gifted and wise, is a fun character. L’Engle’s real achievement, though, is with Meg. She’s every unsure adolescent. She sees herself as ugly compared to her mother, unpopular next to Sandy and Denys, and dumber than Charles Wallace. Suddenly, she’s thrown into a deadly adventure and must force herself to face terrible fears and seemingly insurmountable odds. Alexander and Le Guin wrote about learning responsibility, obviously a valuable lesson. L’Engle wrote about overcoming hopelessness. Maybe even more than responsibility, that’s a lesson worth learning right now.

Following the success of A Wrinkle in Time, L’Engle wrote several more books about Meg, her siblings, and, later, her own children. The only two I’ve read are A Wind in the Door (1973) and A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978). Both are excellent. The others are Many Waters, The Arm of the Starfish, Dragons in the Waters, A House Like a Lotus, and An Acceptable Time.

In 2003, there was an inadequate tv movie made of A Wrinkle in Time. It suffered from a poor script and less than impressive special effects. Now, if you’ve somehow avoided the trailers, there’s a giant-budget movie coming out next week starring Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling, and Oprah Winfrey as too-fabulous versions of Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which. I’d like to say I have high hopes, but with the vast quantities of explosions the movie looks to contain — as opposed to the none the book has — I don’t.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now.

Another one I remember fondly. I’m pretty sure the school library had the Dell paperback with the rainbow-winged centaur thing.

I saw the movie preview on TV the other day and had to be told that what I was seeing was a preview for “A Wrinkle in Time.” I was slack-jawed. Why does “Wrinkle” need “improvements” of this sort?

@Joe – It’s a really beautiful little book, well worth revisiting.

@Mark R – Yeah, it’s sadly terrifying.

I read A Wrinkle in Time many times growing up. It introduced me to so many things, like four-dimensional geometry. In a way it seems more like a succession of images than a story, but it draws you in all the same. The Camazotz parts are extremely creepy.

I’ve always found A Wind in the Door a bit of a slog. The microbiological parts get too abstract and talky. I haven’t read A Swiftly Tilting Planet in a long time, but I recall liking it. And I’ve always been especially fond of Many Waters, which combines Biblical mythology with quantum physics, unicorns, and tiny woolly mammoths…

@Raphael – Great description and sort of what I was trying to convey. I left so many things out for new readers to discover on their own.

I have almost no memories of either Wind or Planet despite having read both 2 or 3 times.