Beowulf: A New Telling — Almost Forgotten Childhood Classic

My formative reading years in late elementary school, that Golden Age of preparation to become an adult reader, contains a row of perennial favorites to which I’ve frequently returned. Madeleine L’Engle, Lloyd Alexander, John Christopher, Zilpha Keatley Snyder, John Bellairs, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, and that’s only getting started. But for mysterious reasons, one book often slips through the cracks of memory, even though it had an enormous influence on my later interests in history, literature, and myth: Beowulf: A New Telling by Robert Nye. When I do recall it from the marshland of childhood memory, its prose and images are as vivid as any other juvenile book I embraced in fourth and fifth grade. The pictures it conjured in my mind are the ones I still see when reading the original poem. There’s no denying the quality of a work that had such a powerful effect on my conception of Beowulf.

My formative reading years in late elementary school, that Golden Age of preparation to become an adult reader, contains a row of perennial favorites to which I’ve frequently returned. Madeleine L’Engle, Lloyd Alexander, John Christopher, Zilpha Keatley Snyder, John Bellairs, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, and that’s only getting started. But for mysterious reasons, one book often slips through the cracks of memory, even though it had an enormous influence on my later interests in history, literature, and myth: Beowulf: A New Telling by Robert Nye. When I do recall it from the marshland of childhood memory, its prose and images are as vivid as any other juvenile book I embraced in fourth and fifth grade. The pictures it conjured in my mind are the ones I still see when reading the original poem. There’s no denying the quality of a work that had such a powerful effect on my conception of Beowulf.

When I recently picked up a copy of Nye’s book, I discovered it retains its potency as both a great story and a reflection of the magic of the actual poem. Some of Nye’ sentence structures are simplified for middle-grade readers, and his prose retelling can’t match the authenticity or allure of an Anglo-Saxon epic poem composed over twelve hundred years ago. But its achievement as a short novel version of Beowulf impressed me enough on this re-read that I want to buy cartons of it and ship them to elementary schools. Hey, you kids who like Harry Potter! Here’s a short fantasy book with three great monsters in it, and it’s super violent and gory, but that’s totally okay because it’s a version of the first classic of English poetry. It’s educational: your parents can’t stop you! (Okay, I won’t guarantee that last part …)

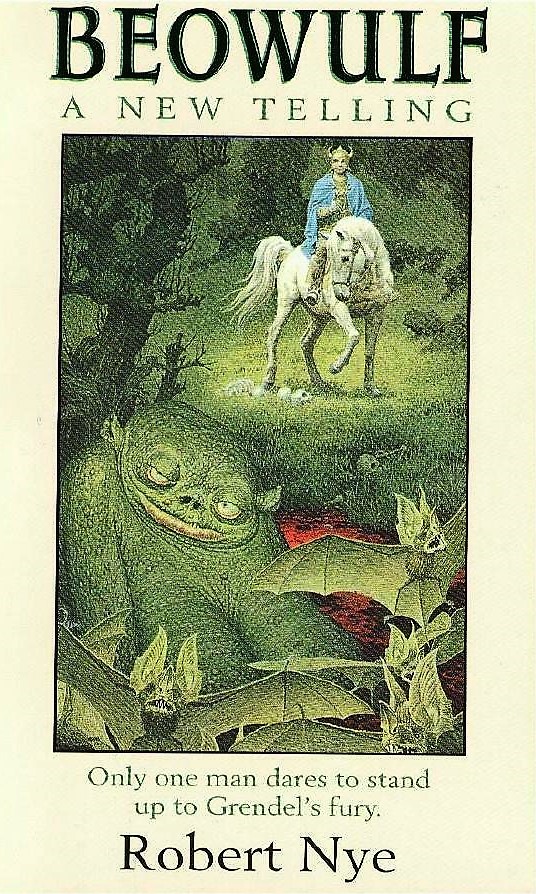

Beowulf: A New Telling was published in 1968, although it felt new when I first read it around 1982. A teacher had recommended the book to our class for extra credit and gave us a short summary of its background: a modern re-telling of a poem by an unknown author. The original was written in the foundling days of English, possibly the eighth century. I bought a copy at a school book fair, and my blood thrilled at the haunting cover: the hero astride a horse, riding into a damp fen aflutter with bats, the monster Grendel (or perhaps Grendel’s Mother) lurking in the corner waiting for him.

In his brief introduction, Robert Nye describes his purpose in writing the book: “This is an interpretation, not a translation. Myth seems to me to have a peculiar importance for children, as for poets: it lives in them.” I don’t recall how I reacted to these words when I first read them, but I recognize in them the child I was at the time. Myth turned into a vital part of my life at an early age when I found Greek mythology. The love of myth and the fantastic within it carried into my adulthood, burgeoning until it became probably the dominant force in my mental world.

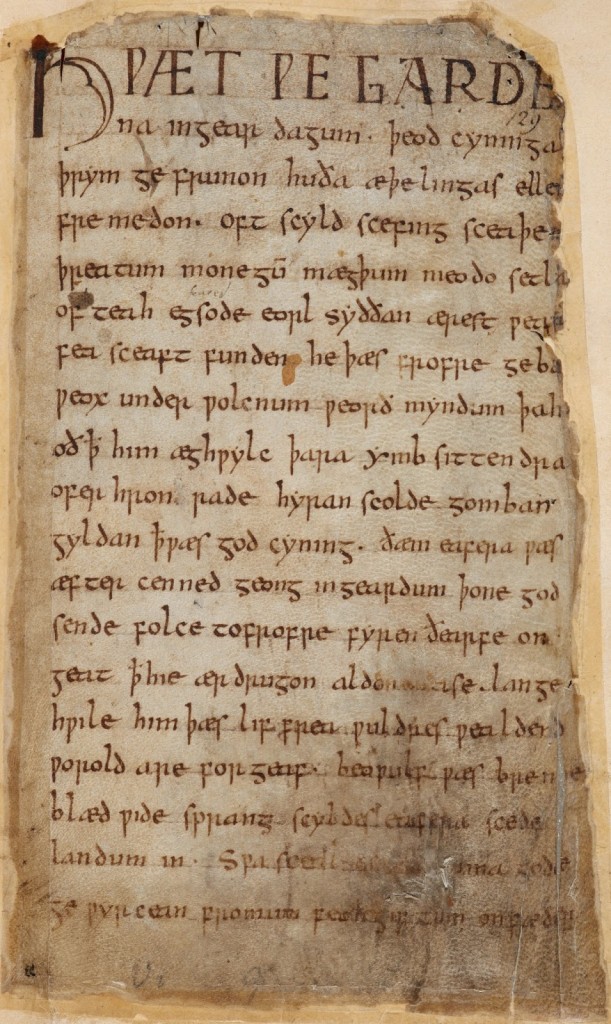

The full story of Beowulf and its three-part division — Grendel, Grendel’s Mother, the Dragon — is here, as are most of the characters. Nye trims some of the ancestral genealogy diversions, although not all. The first chapter cleaves to the original poetic structure and tells of Scyld Scefing, King of the Danes, who is the grandfather of Hrothgar, the king who builds the hall of Heorot that gets the story proper in motion. A writer aiming for a young audience might skip the Scyld Scefing business and shoot straight to a cliché opening chapter: “Once there was Danish king named Hrothgar, who built a great golden hall.” After all, you don’t have to know anything about Hrothgar’s lineage before the bloody events at Heorot … unless you want to have a sense of what old Anglo-Saxon poetry feels like and the unusual workings of early medieval kingship. By opening with Scyld Scefing just as the poem does, Nye announces he won’t violate the spirit of the Beowulf poet just to follow standard novel conventions.

A New Telling makes changes, of course. The account of the Geat-Swedish war woven into the battle with the dragon in the final third of the poem is condensed and put in its chronological place. Some of the characters are expanded: Unferth, Hrothgar’s thyle (“orator” or “jester”), is given a meatier role and goes mad after Grendel’s death. His grotesque characterization is one of the prose version’s highlights. The biggest changes are to the deaths of Grendel’s mother and the dragon (which Nye calls “the firedrake”). In the poem, Beowulf slays each with a sword. Nye follows the thread of Beowulf refusing to use a sword against Grendel and has him also kill the other monsters with different means. He uses the force of his spirit to subdue Grendel’s Mother into a stupor before he throttles her. It’s a daring idea, and I recall my youthful captivation at a sequence where the hero talked a monster to death. The firedrake dies through a trick where Beowulf, with the assistance of Wiglaf, drives a swarm of bees down the creature’s gullet and it’s stung to death from the inside. It sounds a touch silly, but on the page it works.

A New Telling makes changes, of course. The account of the Geat-Swedish war woven into the battle with the dragon in the final third of the poem is condensed and put in its chronological place. Some of the characters are expanded: Unferth, Hrothgar’s thyle (“orator” or “jester”), is given a meatier role and goes mad after Grendel’s death. His grotesque characterization is one of the prose version’s highlights. The biggest changes are to the deaths of Grendel’s mother and the dragon (which Nye calls “the firedrake”). In the poem, Beowulf slays each with a sword. Nye follows the thread of Beowulf refusing to use a sword against Grendel and has him also kill the other monsters with different means. He uses the force of his spirit to subdue Grendel’s Mother into a stupor before he throttles her. It’s a daring idea, and I recall my youthful captivation at a sequence where the hero talked a monster to death. The firedrake dies through a trick where Beowulf, with the assistance of Wiglaf, drives a swarm of bees down the creature’s gullet and it’s stung to death from the inside. It sounds a touch silly, but on the page it works.

Nye says in the introduction that although he was often loose with the poem’s text, he hoped he stuck to its root meaning. I believe he succeeded. Although the writing drops into an occasional over-simplified sentence, Nye creates many stirring phrases that evoke the intricate and elegant metaphors of the Beowulf poet. Scyld Scefing’s “laughter cracked stones.” Hrothgar has “eyes like naked swords.” Grendel makes a noise in its throat “like the crunching of bones or the sudden fracture of ice underfoot.” Reading these phrases makes me want to run over to the original and start drinking in its boatswords, hall-thanes, hell-thoughts, and battle-hearts.

The violence of the original, the part you’d expect a modern writer to dilute for the target audience, appears in all its gruesome bone-cracking fury. Here is Grendel claiming one of the Geats in the mead hall before Beowulf attacks him:

Grendel tore his victim limb from limb, picking off arms and legs, lapping up the blood with a greedy tongue, taking big bites to crunch up bones and swallow gory mouthfuls of flesh. In a minute all that was left of the man was a frayed mess of veins and entrails hanging from the monster’s mouth.

I believe this was the single most grotesque thing I’d read in my life at that point. It’s also a remarkable parallel to the poem, showing how well Nye created the sensation of the Anglo-Saxon poet in modern prose (from the Frederick Rebsamen translation, my personal favorite):

Nor did that thief think about waiting

but searched with fire-eyes snared a doomed one

in terminal rest tore frantically

crunching bonelocking crammed blood-morsels

gulped him with glee. Gloating with his luck

he finished the first one his feet and his hands

swallowed all of him.

Nye gives Beowulf a background with bees not present in the poem. Nye describes the name Beowulf as meaning “bee-hunter” (literally, “bee-wolf”), which is one possible interpretation of the name, and uses this to create a running metaphor. A swarm of bees stung Beowulf as a child, which may have contributed to his poor eyesight. Beowulf turns this limitation into a strength: “His eyes being poor, he determined to see not just as well as other people, but better than most. He did this by cultivating habits of quickness and concentration that enabled him to be truly seeing where others were only looking.” The poem had no equivalent to this, but it gives a reader a sense of the mystery of the Beowulf in the original. The bees make a dramatic re-entrance in the finale, serving as the elderly Beowulf’s weapon against the dragon. Nye captures some of the elegiac tone of the poem’s conclusion with this wrap-around device. It’s not as heavy as the Anglo-Saxon closer. Few things could be.

I don’t know if Beowulf: A New Telling has a presence in schools today the way it did when I was a child. I hope it does, although I can already hear the parent complaints flooding school offices after Mom and Dad discover passages such the graphic description of the decapitated head of Unferth or that Grendel’s Mother has “eyes in her breasts.” Beowulf is one of the foundation blocks of the English language, but it’s also unique and unlike anything else in later English literature. A New Telling is a gateway for younger readers into the dawn of English and the history of the fantastic. If some teacher in the future forgets to assign Beowulf for a class, those students who grew up on Robert Nye’s lean re-imagining may go seek the original for themselves. That’s the route I took. As Nye states at the conclusion of his introduction, “To me, it is an essential story, and therefore never to be fixed.”

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. His most recent publication, “The Invasion Will Be Alphabetized,” is now on sale in Stupendous Stories #19. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a marketing writer. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Robert Nye, eh? I glimpsed him once in Kinsale – a seaside town in Cork, where I think he lives. I remember him primarily as the author for a work of high-end literary erotica: ‘Merlin, Darkling Child of Virgin & Devil’.

This book is alive and well, in my classroom anyway! My grade 7 and 8 students loved the book! No parent complaints yet.