A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin

As I wrote last time, this excursion through the bookshelves of my younger days was inspired by the recent death of Ursula K. Le Guin. I haven’t read much Le Guin outside the Earthsea books; most of her work hasn’t appealed to me. But the Earthsea books, especially the initial trilogy — A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), The Tombs of Atuan (1970), and The Farthest Shore (1972) — did and, I was glad to find out, still do.

As I wrote last time, this excursion through the bookshelves of my younger days was inspired by the recent death of Ursula K. Le Guin. I haven’t read much Le Guin outside the Earthsea books; most of her work hasn’t appealed to me. But the Earthsea books, especially the initial trilogy — A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), The Tombs of Atuan (1970), and The Farthest Shore (1972) — did and, I was glad to find out, still do.

In my article, “Why I’m Here: Part Two,” I described the Elric books as being like samizdat passed around between my friends and me. With so few books actually out there, we fellow fantasy fans read anything we could find, and in turn got it all into everyone else’s hands and read everything they passed along to us. After The Lord of the Rings, I’m sure there were no books as read, and read as often, as Le Guin’s three slender volumes.

There are several whys. The easiest is they are way cool, at least the first and the third. The second is more of a Gothic, and lacks the dragon-battling and dark magic of the others, like this:

At the entrance of the harbor, a shallow crescent bay, he let the windspell drop and stilled his little boat so it lay rocking on the waves. Then he summoned the dragon: “Usurper of Pendor, come defend your hoard!”

His voice fell short in the sound of breakers beating on the ashen shores; but dragons have keen ears. Presently one flitted up from some roofless ruin of the town like a vast black bat, thin-winged and spiny-backed, and circling into the north wind came flying towards Ged. His heart swelled at the sight of the creature that was a myth to his people, and he laughed and shouted, “Go tell the Old One to come, you wind-worm!”

For this was one of the young dragons, spawned there years ago by a she-dragon from the West Reach, who had set her clutch of great leathern eggs, as they say she-dragons will, in some sunny broken room of the tower and had flown away again, leaving the Old Dragon of Pendor to watch the young when they crawled like baneful lizards from the shell.

The young dragon made no answer. He was not large of his kind, maybe the length of a forty-oared ship, and was wormthin for all the reach of his black membranous wings. He had not got his growth yet, nor his voice, nor any dragon-cunning. Straight at Ged in the small rocking boat he came, opening his long, toothed jaws as he slid down arrowy from the air: so that all Ged had to do was bind his wings and limbs stiff with one sharp spell and send him thus hurtling aside into the sea like a stone falling. And the grey sea closed over him.

When I started gaming, everybody who played a wizard wanted to be like Ged. There may have been all sorts of big themes in Le Guin’s books, but they were not what grabbed me. Few twelve-year-olds are going to become fans of a book because of a discourse on the need for equilibrium in the universe, no matter how well presented. But a wizard killing a dragon with a single spell, well, that will make fans.

When I started gaming, everybody who played a wizard wanted to be like Ged. There may have been all sorts of big themes in Le Guin’s books, but they were not what grabbed me. Few twelve-year-olds are going to become fans of a book because of a discourse on the need for equilibrium in the universe, no matter how well presented. But a wizard killing a dragon with a single spell, well, that will make fans.

The next thing that made us fall in love with the books was the world of Earthsea. The universe that sprung from Le Guin’s mind is made up of a endless ocean covered with thousands of islands, and described in concise, poetic prose. Magic is woven into every aspect, from herders who can command goats, to weatherworkers who can summon favorable winds, to full wizards who can change themselves into dragons.

She spun songs and stories about the world’s creation, its legends, and its heroes. The world itself is made of diverse parts, many with their own histories, cultures, and even sorceries. It’s a richly detailed and lovingly brought-to-life setting that leaves the smell of sea air and electric crackling of magic lingering in the air after the last page is turned.

Even though she was writing before the total commodification of fantasy, Le Guin was determined not to replicate the Northern European setting that was already becoming the genre’s default. Earthsea’s cultures seem vaguely medieval, and its primary ethnic groups range from red-hued to dark black. Only the warlike Kargish are white-skinned and blond. I’m not sure how much attention I paid to this aspect when I first read the series, but it definitely helped set the stage for not automatically assuming everyone in a fantasy book would be white.

A Wizard of Earthsea follows the training and travails of a boy named Ged from an insignificant town on a minor island, Gont. The story starts with his early attempts at magic learned from his aunt, the village witch, to his training under the wizard Ogion, and finally his serious study of the great secrets of sorcery at the School on Roke. Earthsea’s wizard school may not be the first in fiction (though no earlier come to mind), but it’s the one that most informed my idea of what such a place should be. The Archmage Nemmerle, a man “older, it was said, than any man then living” and with a voice that “quavered like a bird’s,” immediately became what I imagined the head of every such place should be.

The Archmage looked at Ged and looked away, and began to speak in a tongue that Ged did not understand, mumbling as will an old old man whose wits go wandering among the years and islands. Yet in among his mumbling there were words of what the bird had sung and what the water had said falling. He was not laying a spell and yet there was a power in his voice that moved Ged’s mind so that the boy was bewildered, and for an instant seemed to behold himself standing in a strange vast desert place alone among shadows. Yet all along he was in the sunlit court, hearing the fountain fall.

A great black bird, a raven of Osskil, came walking over the stone terrace and the grass. It came to the hem of the Archmage’s robe and stood there all black with its dagger beak and eyes like pebbles, staring sidelong at Ged. It pecked three times on the white staff Nemmerle leaned on, and the old wizard ceased his muttering, and smiled. “Run and play, lad,” he said at last as to a little child. Ged knelt again on one knee to him. When he rose, the Archmage was gone. Only the raven stood eyeing him, its beak outstretched as if to peck the vanished staff.

While at the school on Roke, Ged’s excessive pride about his talents, wounded by the dismissive taunts of an older student, leads him to commit an act of sorcery with awful consequences, among which are a fatality and Ged’s own near death. Most importantly, he summoned up a terrible thing that will later chase him across half of Earthsea:

While at the school on Roke, Ged’s excessive pride about his talents, wounded by the dismissive taunts of an older student, leads him to commit an act of sorcery with awful consequences, among which are a fatality and Ged’s own near death. Most importantly, he summoned up a terrible thing that will later chase him across half of Earthsea:

“Lord Gensher, I do not know what it was—the thing that came out of the spell and cleaved to me—”

“Nor do I know. It has no name. You have great power inborn in you, and you used that power wrongly, to work a spell over which you had no control, not knowing how that spell affects the balance of light and dark, life and death, good and evil. And you were moved to do this by pride and by hate. Is it any wonder the result was ruin? You summoned a spirit from the dead, but with it came one of the Powers of unlife. Uncalled it came from a place where there are no names. Evil, it wills to work evil through you. The power you had to call it gives it power over you: you are connected. It is the shadow of your arrogance, the shadow of your ignorance, the shadow you cast. Has a shadow a name?”

The remaining half of the book is built around Ged’s initial evasion of the shadow and his subsequent hunt for it. In an increasingly dark series of adventures, the shadow draws nearer to him while other dark forces try to lure him into their own trap. Once he determines to fight back, the story takes on a brighter tone. The final confrontation between Ged and the shadow might strike some as anticlimactic, but even at twelve, I found it perfect. It brings Le Guin’s theme of balance to the fore, and points toward an elimination of further harm, if not a restoration.

Though told with style and plotting quite different from Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three (reviewed last week), it covers some of the same basic ground: a young man learning about the costs of his actions and the burdens of responsibility. It’s a ripe subject for a young adult book, and when it’s handled as well as it is here, it can resonate strongly with even a middle-aged reader. A Wizard of Earthsea is an inventive and compelling read, well-worth picking up for the first time or the fifth.

The next book in the original series, The Tombs of Atuan, is essentially a Gothic, complete with naive young woman, haunted tunnels, a malevolent Mrs. Danvers-like priestess, and Ged as an alluring temptation from the world beyond the temple confines. The Farthest Shore explores, in great and terrible detail, what happens when the natural balance of the world is upended for the most selfish of reasons.

Years after The Farthest Shore was published, Le Guin returned to the series with two more novels: Tehanu (1990) and The Other Wind (2001). They were written expressly to address issues of gender, and are told from an explicitly female perspective. I remember liking them, though they haven’t drawn me back multiple times like the original books have. I might go back to them this time around.

Finally, two films have been made based on Le Guin’s books. The first, and a most awful thing it is, is the tv miniseries, Earthsea (2004). It made most of the non-white characters white, and inspired two long, angry pieces from Le Guin about the perfidy of Hollywood: “A Whitewashed Earthsea,” and “Frankenstein’s Earthsea.” There’s also a movie, Tales from Earthsea (2006), directed by Goro Miyazaki. I haven’t seen it, but I do know Le Guin wasn’t happy with it for all the liberties it took with her work.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now.

Great article! I also recently reread the original trilogy, and was very pleased with how well they held up.

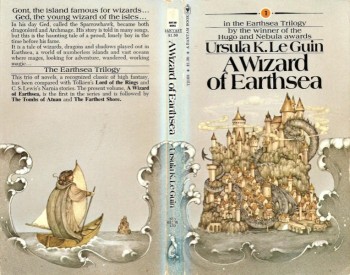

My favorite covers were always the Bantam ones, although I’m pretty sure there was some whitewashing going on there.

I’ve never subjected myself to the SyFy miniseries. I’ve watched the Ghibli film a few times and generally enjoyed it, although enjoyment requires taking it on its own terms as a Ghibli fantasy movie entirely divorced from the source material — it’s very pretty and has a great soundtrack. The story is very, very loosely based on The Farthest Shore, but it has about the same relationship to the book as Howl’s Moving Castle did to its original.

Not the first time I’ve said this – OK, maybe the first time I’ve said it on Black Gate – but my reaction on re-reading the first three books a couple of years ago was in sharp contrast to how they affected me as a teenager. Ged seemed uber-cool to me, back then. Now I find ‘The Tombs of Atuan’ – originally my least favourite – the most powerful of the three.

My favourite Le Guin novel – also a YA fantasy story – is ‘Threshold’, which I think was called ‘The Beginning Place’ in the US (and maybe in Canada, too?). I have yet to read ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’.

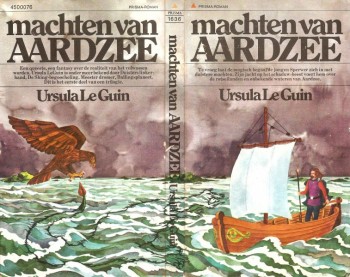

The covers for the original Earthsea Trilogy on this side of the pond (and at that time) were all by David Smee.

http://gnomeship.blogspot.ie/2016/08/the-farthest-shore.html

@Joe – Yeah, the Bantams for me too. Sure, Ged’s whiter than he should be and I don’t picture any city on Earthsea looking like that, but it’s the one I grew up with and everybody I knew owned.

I definitely want to see the Miyazaki movie, despite knowing it’s not the books.

@Aonghus – Me too, regarding Tombs. It bored me and my friends silly as a kid – though apparently not enough to skip it any time we reread the series. Now, I think it’s the best of the trio.

I’ve only read a little of her other work and never found it very satisfying.

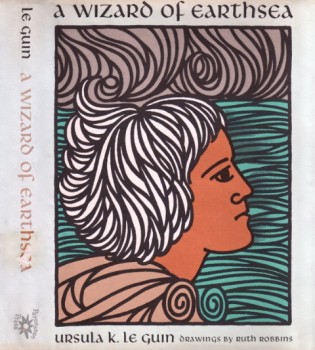

Wow, I’ve never seen that cover. I like it.

Yeah, that’s a great cover. And I also agree that when I reread the books recently, I thought Tombs might’ve been the strongest of the three, although I enjoyed them all.

Aonghus – the original cover for the first paperback UK edition was by Brian Hampton. This was in 1971. You can see it here:

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=22742572900&searchurl=tn%3Dwizard%2Bof%2Bearthsea%26sortby%3D17%26pics%3Don&cm_sp=snippet-_-srp1-_-title6

It has some notoriety because the artist ignored the skin colours of the people of the Archipelago and drew Ged with a white face and hands. I read somewhere that Le Guin, who was living in London at the time, was extremely upset. She had a right to be angry. I read that edition – I still own it. I was 14 when it came out and, for years, imagined the inhabitants of Earthsea as white – despite what it actually says in the text. Later, as I read more about Earthsea, I realised my mistake but the damage had, by then, been done. Looking at the David Smee illustrations, they also seem to have misrepresented the Earthsea inhabitants. Neil

That’s some cover! I wonder if Hampton even read the book? I’m pretty sure that Ged (even disregarding how he wasn’t white) didn’t dress like some renaissance prince. Interesting to see it’s a Puffin publication, as the Smee illustrations were for puffin as well. He seems to have done different covers for both the hardcopy and paperback versions. Take the Tombs of Atuan –

Here’s his cover for the hardback (which I really like and have never seen before).

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/first-edition/Tombs-Atuan-Ursula-K-Guin-Gollancz/22365646978/bd#&gid=1&pid=1

Here’s his cover for the paperback.

https://www.biblio.com/book/tombs-atuan-puffin-first-edition-guin/d/367033142

Aonghus — THRESHOLD was indeed originally called THE BEGINNING PLACE (and still is, in the US, and I imagine that’s Le Guin’s preferred title). I reread it right after Le Guin’s death and reviewed it here:

http://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2018/02/two-of-ursula-k-le-guins-lesser-known.html

That’s a great review, Rich. One thing I kind of liked about ‘Threshold/The Beginning Place’ is you’re never quite sure if the two kids are heroes going out to fight the monster, or sacrificial lambs – and just how complicit the townspeople are in this regard.

That’s exactly right, I think, Aonghus, and the different sorts of complicity displayed by the Master and the Lord are interesting as well.