Shark Ships and Marching Morons: The Best of C. M. Kornbluth

|

|

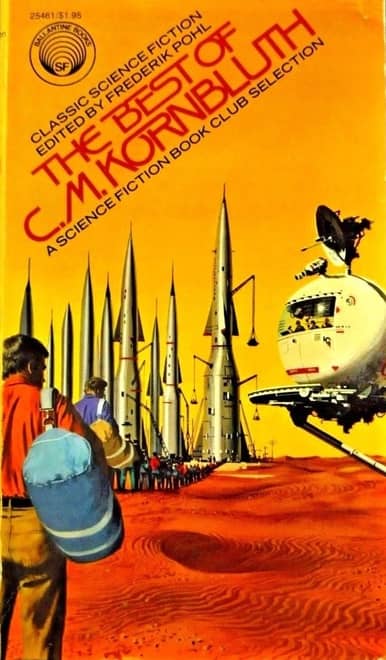

The Best of C. M. Kornbluth (1977) was the eighth installment in Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction Series. Kornbluth’s long time friend and collaborator Frederik Pohl (1919-2013) served as editor; he also provided an introduction and brief intros to each story. Dean Ellis (1920-2009), who did the cover art for the first four volumes, returns to the series to do the cover art for this one — a scene from “Marching Morons.” Unlike previous volumes, there is no afterword.

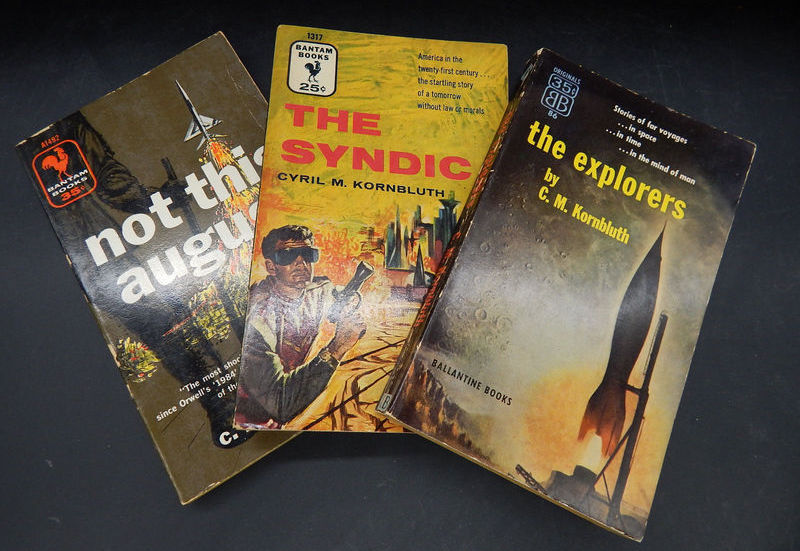

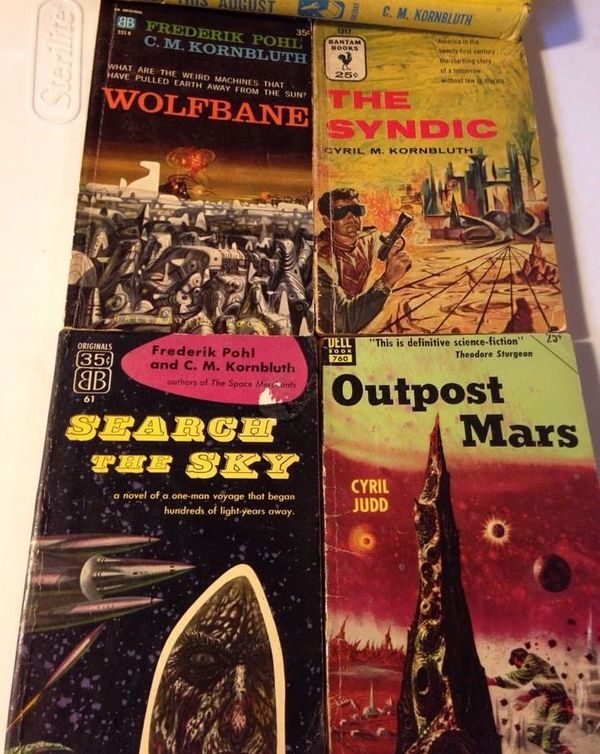

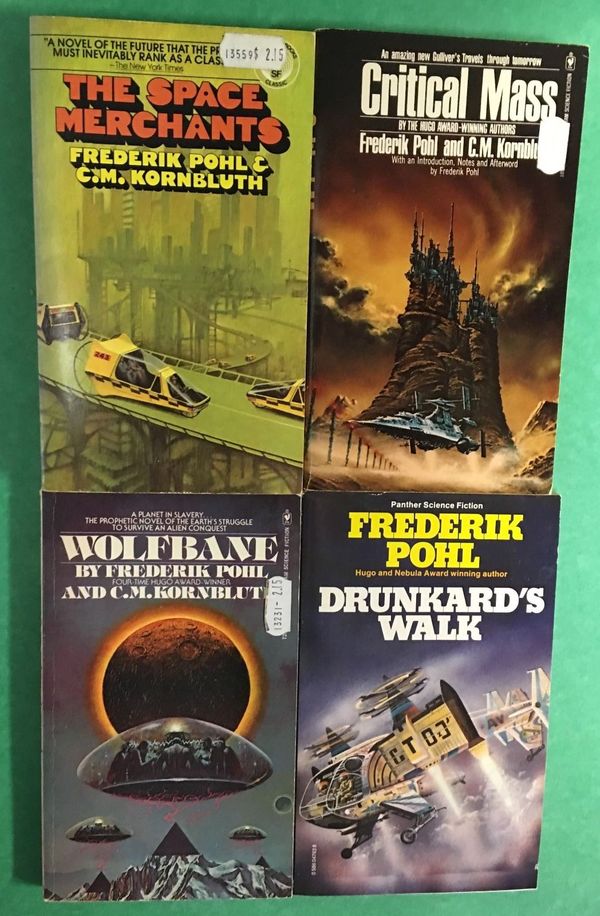

Cyril M. Kornbluth (1923–1958) was an original voice in American science fiction. His middle initial “M” apparently stood for a non-existent name, and was meant to include his wife Mary, whom he hoped would eventually collaborate with him, but this evidently never materialized. Though he died at a very young age, his fiction corpus was long, varied, and lasting. He is probably most remembered today for his very influential novel The Space Merchants (1953), co-authored with Pohl. It’s strange to me that Korbluth and Pohl collaborated together since their writing styles seem almost polar opposites. But they were lifelong friends, which perhaps explains Pohl’s presence as editor here.

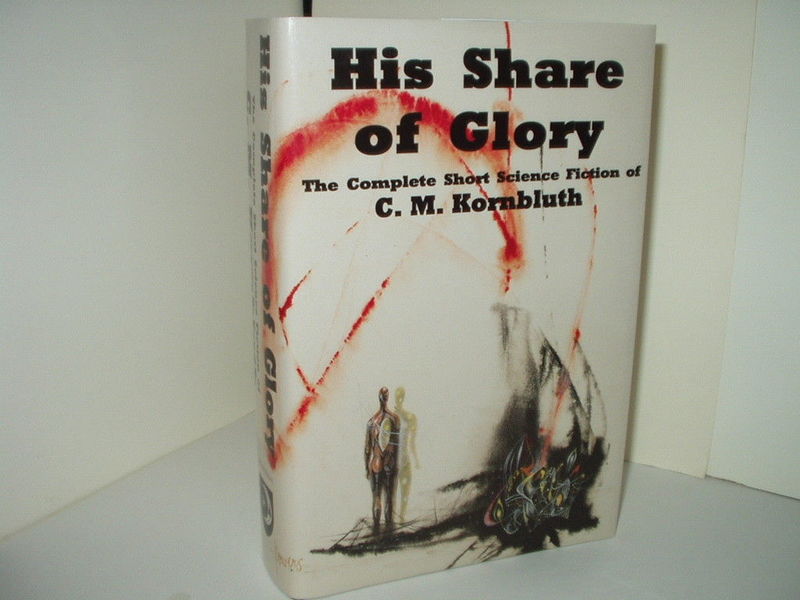

I’ve listened to most of the audible book His Share of Glory: The Complete Short Fiction of C. M. Kornbluth. Though that collection is clearly larger, I think Pohl did an excellent job choosing tales for The Best of C. M. Kornbluth. The stories here are truly representative of Kornbluth’s best.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

Though Kornbluth was clearly an old school sci-fi writer, I think he is very original in his presentation and focus. Many of his stories don’t quite go where you think they will, and Kornbluth seems more interested in the human animal than in science fiction tropes. His tales are not what I would call anti-science or anti-technological, but it is clear that many of Kornbluth’s stories raise concerns about the effect of technological and sociological progress on the individual. This focus is especially showcased in Kornbluth’s gift for characterization. His characters feel real.

For example, “Gomez” is about a young and formally uneducated Hispanic man who is a mathematical prodigy. Once the cold-war American government discovers Gomez, they sequester him to a secret research laboratory to work for them in military research and development. Though Gomez at first is excited about working with professional scientists and mathematicians, he slowly begins to see that he has basically become a prisoner. Without being preachy, “Gomez” highlights the importance of individuality and human freedom in the midst of securing worthy (though not of ultimate worth) national goals.

A similar tale was “Shark Ship” about a futuristic society that many years before was forced to abandon land for the open seas in order to collect enough food for the growing population. Generations have come and gone on these ships, but no word has been heard from land in many, many years. The sea-bound society that has developed on these ships only has legends about “land dwellers.” Impending disaster forces one of the ships to head inland as a last ditch effort, but with great fear and trepidation. They discover many surprises, many about their own selves.

Kornbluth produced several tales that point to worries surrounding the rise of advertising and mass media. One of the more famous, “The Marching Morons” is about a society that has given itself over to technology so much that it no longer cares about thinking all that deeply about anything. John Barlow, a time traveler from the past, devises a “lemming-like” solution to overpopulation. Though Barlow eventually gets his comeuppance, the story is more about the need for human beings to be intelligently engaged with their world despite technology.

Though these themes appear throughout, Kornbluth is also very eclectic. “The Advent of Channel 12” is an experimental piece on children’s television programming, featuring something along the line of a wacky version of the Mickey Mouse club. “Mindworm” is almost a horror story about a psychic vampire of sorts. “Little Black Bag” is about a washed-up doctor who finds an automated medical kit sent from the future. It appeared as a 1970 episode of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery, featuring Burgess Meredith. “Two Dooms” is an alternate timeline story about a scientist working on the Manhattan Project who sees how things would’ve turned out if the United States had not developed “the bomb.” I was prepared for a sort of bleeding-heart moral tale here, but the ending was extremely surprising.

In his introduction Frederik Pohl relates that Kornbluth had been a journalist for several years. I think Kornbluth’s punchy and hooking prose really evidences this. He is a unique writer and utterly unlike any sci-fi writer I’ve read before, especially in this Del Rey series. The Best of C. M. Kornbluth is more than just a collection of good sci-fi tales, but a plethora of well-written stories about what it means to be truly human and truly happy. I doubt Kornbluth set out on agenda to prognosticate some humanistic message. More likely, he simply wanted to write good stories. He definitely succeeded with these tales. But in the end, they leave you thinking about more.

For an interesting and insightful take on science fiction done in an original voice, I can’t recommend The Best of C. M. Kornbluth enough.

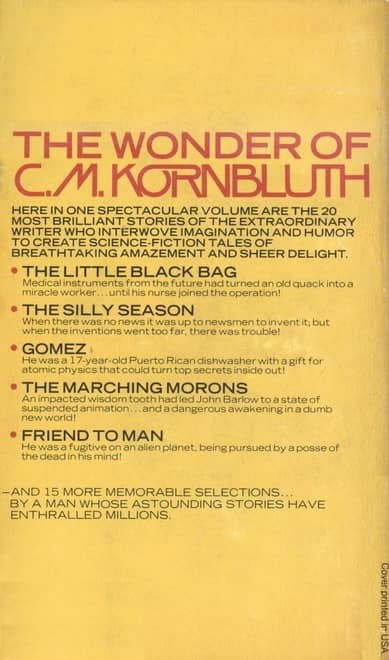

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

An Appreciation by Frederik Pohl

“The Rocket of 1955” (Stirring Science Stories, 1939)

“The Words of Guru” (Stirring Science Stories, 1941)

“The Only Thing We Learn” (Startling Stories, 1949)

“The Adventurer” (Space Science Fiction, 1953)

“The Little Black Bag” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1950)

“The Luckiest Man in Denv” (Galaxy Science Fiction, 1952)

“The Silly Season” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1950)

“The Remorseful” (Star Science Fiction Stories No. 2, 1953)

“Gomez” (New Worlds #32, 1954)

“The Advent on Channel Twelve” (Star Science Fiction Stories No. 4, 1958)

“The Marching Morons” (Galaxy Science Fiction, 1951)

“The Last Man Left in the Bar” (Infinity Science Fiction, 1957)

“The Mindworm” (Worlds Beyond, 1950)

“With These Hands” (Galaxy Science Fiction, 1951)

“Shark Ship” (Vanguard Science Fiction, 1958)

“Friend to Man” (10 Story Fantasy, 1951)

“The Altar at Midnight” (Galaxy Science Fiction, 1952)

“Dominoes” (Star Science Fiction Stories, 1953)

“Two Dooms” (Venture Science Fiction, 1958)

About the Author (1954) by C. M. Kornbluth

Our previous coverage of the Classics of Science Fiction line includes (in order of publication):

Smugglers, Alien Vampires, and Dark Dimensions: The Best of C. L. Moore by James McGlothlin

Rich Playboys, Mad Scientists, and Venusian Monsters: The Best of Stanley Weinbaum by James McGlothlin

Vampires, Frozen Worlds, and Gambling With the Devil: The Best of Fritz Leiber by James McGlothlin

Space Colonies, Interstellar Fleets, and The Martian in the Attic: The Best of Frederik Pohl by James McGlothlin

A Neglected Master: The Best of Henry Kuttner by James McGlothlin

A Shaper of Myths: The Best of Cordwainer Smith by James McGlothlin

Wings, Wind, and World-Wreckers: The Best of Edmond Hamilton by Ryan Harvey

The Best of Henry Kuttner

The Best of John W. Campbell

The Best of C M Kornbluth

The Best of Philip K. Dick

The Best of Fredric Brown

The Best of Edmond Hamilton

The Best of Murray Leinster

The Best of Robert Bloch

The Best of Jack Williamson

The Best of Hal Clement

The Best of James Blish

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Absolutely one of the greatest short story writers the genre has ever seen. His Share of Glory ought to be owned by everyone.

TP, What’s your opinion of Space Merchants? If you’ve read it, is it still worth reading today?

I remember reading that book (with that cover) back in high school!

Kornbluth was a good writer, but whenever people bring up “The Marching Morons”, I feel the need to point out that there’s some nasty subtext to it. You summarize the future society as “no longer car[ing] about thinking all that deeply about anything”, but the story is really arguing that, if unintelligent people keep having more children than intelligent people, the human race will become less intelligent. The story takes this to extremes, with the people in the future world all being literally morons except for a small caste of eggheads who keep everything running.

This fallacy was a classic argument for eugenics, and in the early 20th century it led to atrocities in the US like involuntary sterilizations of people who were judged to be “inferior” based on their IQ scores, mental health or race. In Germany it went even farther — not just attempted genocide, but also the large-scale slaughter of mental inmates and of children with developmental disorders such as autism. In light of this, the satire of shipping stupid people into space to let them asphyxiate seems pretty unfunny. (And Kornbluth wrote it in 1951, after the death camps were already revealed to the world.)

The story still has some great satire of advertising and public relations, like the way they basically “retcon” the existence of a (fictitious) Venus colony into the public mind, but these ideas are much better developed in his & Pohl’s later novel The Space Merchants.

Thanks for comment snej. But I disagree that the story is “arguing” what you claim. It seems to me that Kornbluth portrays the main character as villainous getting his just desserts at the end, and portrays the “morons” sympathetically, which wouldn’t make sense if you were right.

However, I think you’re on to something; but rather than being the main point that is being argued for, I think it (worded a bit differently) may simply be a result of my summary claim of the story. It makes sense to me that poorly educated people (not necessarily unintelligent) would probably produce a society (i.e. children) who were poorly educated as well. This isn’t a necessary consequence, but it seems to me that it would more than likely be a probable outcome.

Your comment about Space Merchants makes me want to read book though!

It’s been a couple of decades since I read The Space Merchants, but I remember it as being a very pointed satire, and I would think in this era of “Mad Men,” it would just as relevant.

Of the Pohl collaborations, Wolfbane and Gladiator-at-Law are very strange books, but enjoyable in a 50’s “sociological sf” way, especially Gladiator-at-Law, though it’s unable to live up to that incredible title.

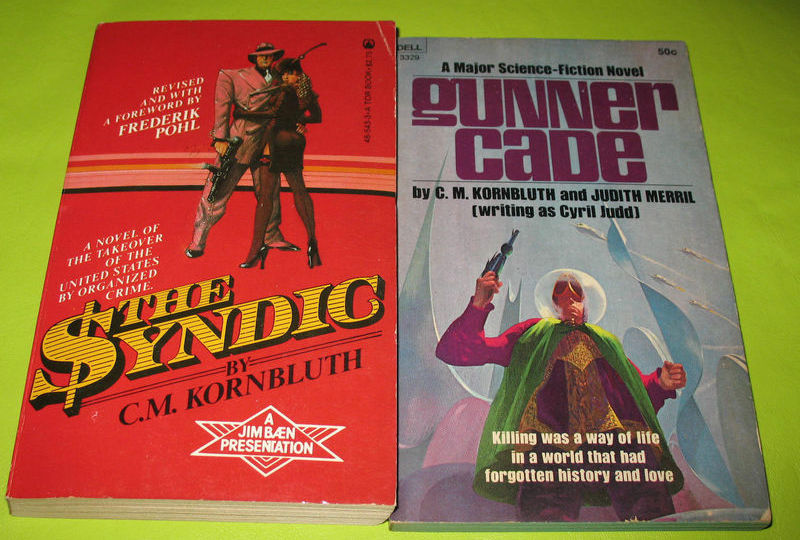

I was disappointed with The Syndic; it seemed to me that Kornbluth didn’t really think it through, or maybe he just lost interest in it.

My favorite Kornbluth story is “The Remorseful.” For me, it will always be the definitive Last Man on Earth story.

It’s been years since I read The Space Merchants but it’s still lodged firmly in my mind and I would think it’s more relevant than ever. When corporations are launching glowing advertisements and cars into space and people can’t distinguish what’s real and not and what’s valuable and not, it’s relevant. A true classic. Beware that there is a later revision done by Pohl alone which, to be fair, I haven’t read, but which would probably damage the book. Changing company names doesn’t change or improve the theme or quality of fiction and changing more (which I think he did a little of) makes it no longer the classic which people read for over thirty years (or however long it was before he revised it). So I do strongly recommend it and recommend the original. I also think the two of the other three Pohl/Kornbluth novel collaborations are very strong (Gladiator-at-Law, Wolfsbane) though Search the Sky is an oddly half-baked collage derivative of some of their other, better works – it’s not awful, but it’s not necessary.

Anyway – back on the solo Kornbluth, I agree that he was a remarkable talent (and his early death was a tragic and major loss to the field) and that Pohl did a fantastic job selecting the stories. There is at least one great story he missed (which I can’t think of now) but it’s been anthologized, if I’m not mistaken. Generally, while I’d love to have the complete collection just because, I’m happy with my TBO.

snej,

I know exactly what you mean about the eugenics argument in “The Marching Morons,” and I recall being quite alarmed for exactly that reason the first time I read it. But if I remember correctly (and it’s been a few years), I think James has it exactly right with the ending, in which the racist narrator, who says he “wouldn’t do his best work” while working with black co-workers, gets a nasty comeuppance.

And my favorite Kornbluth story has to be “The Altar at Midnight.” “The Little Black Bag” blew me away when I was a kid. “The Altar at Midnight” blew me away when I was 50 years old. There aren’t many stories from the 1950s that can do that any more.

Thanks for this great review of some of my favorite work.

The “Marching Morons” argument pops up repeatedly–the movie Idiocracy is a fairly recent version, and Pohl&Kornbluth also used it again (with a more humane resolution, or lack thereof) in Search the Sky. Lots of people who should know better have fallen for the mistaken belief that high socio-economic class = high intelligence. As genetics goes, it’s obviously wrong-headed, but one can argue that it’s not what Konbluth’s story was really about. As a Jewish combat veteran from WWII, he wouldn’t have had much sympathy for Nazi practices.

I was intrigued by Thomas Parker’s reaction to The Syndic–it’s always been one of my favorites. In fact, I’d rank it just below The Left Hand of Darkness as one of the greatest science-fiction novels ever written. De gustibus non disputandum, I guess.

“Shark Ship”, with its intensely pessimistic view of human nature, remains his most disturbing story, in my view. Frederik Pohl said of his friend that “He had a thing for death and destruction” and this is the story where it’s most obvious. But it’s not a completely hopeless story, for all of that.

Thanks again for the review. Time for some rereads, maybe.

[…] Black Gate » Shark Ships and Marching Morons: The Best of C. M. Kornbluth […]

About 10 years after CM Kornbluth’s death I read Marching Morons. That story has stayed with me even after I had forgotten the author’s name. Today it’s foremost in my mind to today’s political situation. I am now determined to read everything he ever wrote!