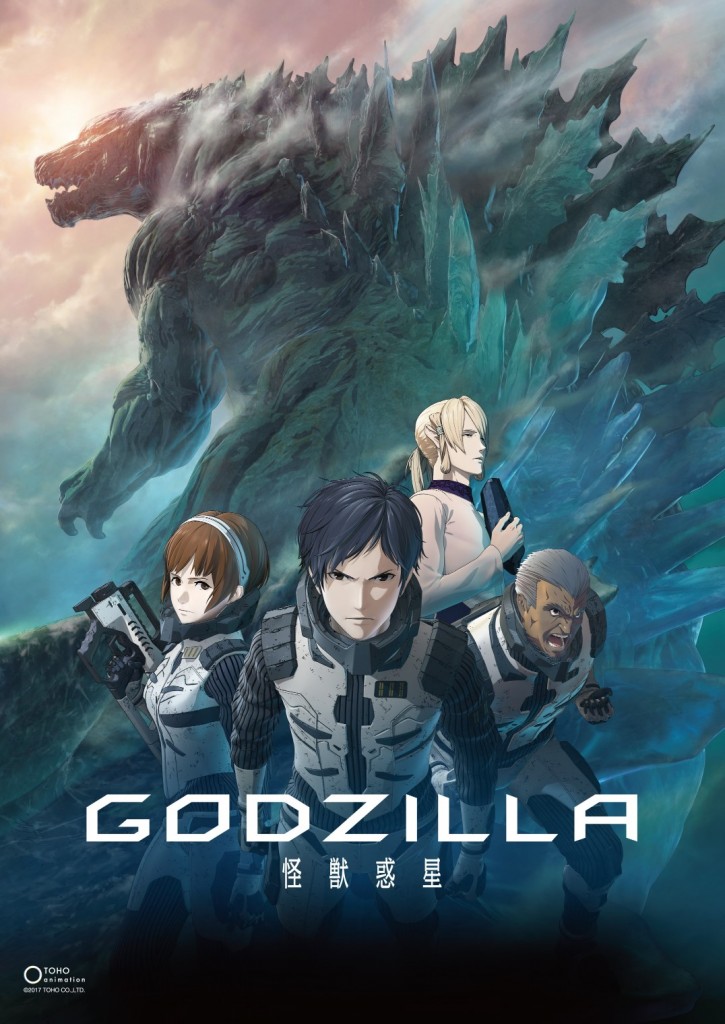

The Animated Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters Mostly Does Its Job

Go-ji-ra — a strange word with mythic resonance when it rolls off the tongue of native Japanese speakers. But it’s a tough sell as the English title of a 1950s monster movie. For the sake of global audiences, the Foreign Sales Department of Toho Studios gave their 1954 movie and its monster a Romanized name: Godzilla. It makes sense as a transliteration: the katakana character shi (シ) in Gojira (ゴジラ) can be Romanized as -dzi-, and the “R” sound in -ra (ラ) slides into an “L.” By happy accident — or sly intention — Toho baptized their behemoth with the word God at its front, hinting at a creature greater than life, dominant in a way no mere monster could be.

The highest compliment I can give to the new animated film, Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters (currently streaming on Netflix), is that it explores and explodes the “God” in Godzilla. Other movies in the series have emphasized the monster’s inscrutability and deity-like unstoppability. The first mention of Godzilla in the 1954 original comes from an old fisherman who speaks of a legendary beast that has kept his island in fear for centuries. Planet of the Monsters pushes this god(zilla)hood into the spotlight. Godzilla has literally conquered Earth, driving the scraps of humanity into exile in space, then transforming and ruling the planet’s ecosystem unchallenged for twenty thousand years. This is Godzilla Earth, where the monster is both creator and destroyer.

Godzilla as the Deadly Almighty is woven deep into the story. The human race are beggars among the stars, searching for a habitable planet as their supplies dwindle along with their hope. Aiding them are two alien races who are also star-wanderers, the proselytizing religious Exif and the engineering Bilusaludo. The Exif are a mouthpiece of the spiritual meaning of Godzilla: “For the species who pronounce themselves as lords of creation, a divine avenger will pay them a visit.” When the vestiges of humanity aboard the ship Aratrum choose to return to their homeworld after a twenty-two-year search — finding twenty-thousand years have passed on Earth during the hyperspace jump — they face more than a monster-slaying mission. Young Captain Haruo Sakaki, spearhead of the attempt to destroy the creature, recognizes Godzilla’s existence as a mockery of humanity. “Godzilla didn’t just steal the Earth away from us,” he says. “Justice, faith, and the basic pride we have as humans … we’ve come to lose them too. And that’s why we need to fight Godzilla again. So we can take back the dignity we lost.” This view of Godzilla will resonate with long-time fans who fell under the monster’s spell at a young age, as well as anyone fascinated with the giant monster genre.

It’s a touch disappointing that such grand themes are in a movie that can’t fully achieve the promise of its epic title or the potential of the animation medium. The first animated Godzilla movie is a stellar opportunity to go all-out-assault free of the restraints of expensive sets, props, and monster costumes. The CGI animation by Polygon Studios is often striking — attack sleds swooping around Godzilla’s bulk, the grotesque plant growth of the altered Earth, the steel-gray color scheme. But it’s too contained for an epic involving alien races, hyperspace travel, planet colonization, and mechas in combat with a globe-crushing monster.

It’s a touch disappointing that such grand themes are in a movie that can’t fully achieve the promise of its epic title or the potential of the animation medium. The first animated Godzilla movie is a stellar opportunity to go all-out-assault free of the restraints of expensive sets, props, and monster costumes. The CGI animation by Polygon Studios is often striking — attack sleds swooping around Godzilla’s bulk, the grotesque plant growth of the altered Earth, the steel-gray color scheme. But it’s too contained for an epic involving alien races, hyperspace travel, planet colonization, and mechas in combat with a globe-crushing monster.

A flashback montage shows kaiju “from the depths of the earth and sea, or even from forgotten divine myths” assaulting Earth in the year 2000. Established Toho monsters appear: Kamacuras, Orga, even Dogora the space jellyfish from its eponymous 1964 film. (A weird, weird movie combing kaiju action with a diamond heist caper.) This superbeast offensive recalls Pacific Rim, except the humans never defeat the monsters. They don’t even get their single giant robot, Mechagodzilla, into motion before Godzilla toasts everything. But these monsters are only cameos, a brief fanfare announcing the King, and never seen again. The “planet of monsters” the humans find millennia later is only Godzilla and few smaller flying beasts called the Servum that mutated from Godzilla cells. Or at least this is all the audience gets to see.

A Godzilla film doesn’t necessarily require an all-star monster supporting cast, or even another kaiju of Godzilla’s stature. But a movie subtitled Planet of the Monsters with a setting of a bizarre fauna should have more surprises than one extra species of mini-dragon. The alien-earth canvas recalls the worlds of Anne McCaffrey, Jack Vance, and Andre Norton, but without pushing far enough into that baroque potential. Plus, this is animation. Going a bit more “Gamma World” won’t break the budget.

Japanese SF films often stagger under the weight of too many characters without enough time to develop them and an excess of unfinished ideas. Planet of the Monsters is setting up two further movies, so the mass of material packed into eighty-minutes is almost forgivable. But the large cast of characters and the heavy SF background makes it difficult to get involved in the opening sequences aboard the Aratum. An early scene between the Exif priest Metphies and the Bilusaludo leader Galu-Gu is so dense with exposition that viewers may have to skip back and rewatch it to grasp what they’re talking about. The Exif and their spiritual philosophy unfold gradually across the movie and are the best handled of the SF elements, even if they leave behind many questions about their intentions spreading their religion. The mecha-building Bilusaludo, however, remain ciphers. At times it’s easy to forget they’re even aliens. Of the human characters, Captain Sakaki is the only one who steps out from the crowd thanks to his passion.

Godzilla takes its time making a re-entrance after the opening montage, waiting almost fifty minutes before thundering back into view. This isn’t a huge detriment, except maybe for younger viewers; the slow build is a tradition with kaiju films. But when Godzilla does appear on Earth to face the expedition from the Aratrum, the movie doesn’t switch to a higher gear. The Godzilla design is wonderful, looking as if the monster were made of solidified lava flows, and the overall outline resembles the hulky look from Godzilla ‘14. But Godzilla is almost immobile in the battle scenes and pulls few of the awe-inspiring moves the monster often flexes. A few targeted atomic breath blasts, a tail sweep … otherwise the motion is all left to the humanoid attackers in their mechas and flying vehicles. Except for a brief return of the Servum to ambush the sky-sleds, the action for the finale is constant swooping shots circling and diving at Godzilla as they push it toward a trap. The “God” in Godzilla is present — but not the motion or thrills of fighting against the unconquerable.

When the movie knuckles down for this twenty-minute showdown, Planet of the Monsters turns into an orthodox Godzilla narrative. We’ve seen it before: scientists devise a scheme to kill or stop the monster, the military tries to put it into action, a few unforeseen glitches crank up tension, and then the humans succeed or fail. The battle unfolds in CGI animation with a scope impossible for a live-action film (at this budget, anyway) but that’s the only major difference separating it from a dozen other Godzilla films — including the previous one, Shin Godzilla.

The finale may turn off many viewers, even when they know this is only the first part of a trilogy. Anytime a movie essentially hits the reset button when it appears to be wrapping up is taunting audiences to sour on it. But the futility of the ending works for me, since it echoes the incomprehensibility of this Godzilla. A primal human scream of determination and impotence — that’s a good spot for a fast curtain-drop.

Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters succeeds at its basic task, which is to show Godzilla can exist in the anime format and still feel like the classic monster. It loses the stunt actor in the suit and the miniature buildings and military assault vehicles, but what’s on screen is recognizably a Godzilla experience. The movie raises questions to keep Godzilla fans engaged when the credits are over, even if they don’t feel the satisfaction of watching the hard-hitting and weird anime epic they anticipated.

Now it’s up to the second and third films in the trilogy — the next, Godzilla: City on the Edge of Battle, arrives in Japanese theaters in May and probably on Netflix in July — to make good on the potential lying in the rubble of the finale. A brief post-credits teaser hints at where the Part 2 may head, and I’m interested to go on this journey in the hope the anime potential bursts from the confines of scientists and the military battling Godzilla as usual. Mobilize those other monsters! Godzilla can do solos for only so long.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Good review. I thought you’d miss this week after celebrating yesterday. Hope you had a happy birthday.