Birthday Reviews: Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s “Cruxifixus Etiam”

|

|

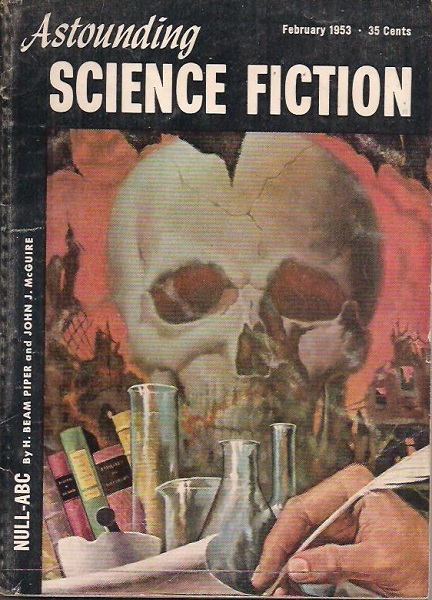

Cover by Van Dongen

Walter M. Miller, Jr. was born on January 23, 1923 and died on January 9, 1996. He is best known for his novel The Canticle for Leibowitz, which won the 1961 Hugo Award for Best Novel. He had previously won the first Hugo Award for Best Short Story for “The Darfsteller” in 1955. He wrote numerous short stories and edited the anthology Beyond Armageddon with Martin H. Greenberg, and left a partial manuscript for a sequel to A Canticle for Leibowitz at his death, which was completed by Terry Bisson and published as Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman.

“Crucifixus Etiam” was originally published in the February 1953 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, edited by John W. Campbell, Jr. It has been reprinted numerous times, including under the title “The Sower Does Not Reap” in The Best Science Fiction Stories: Fifth Series, edited by Everett F. Bleiler and T.E. Dikty (although it was published under its original title in the first edition of the book). Miller included the story in his collections The View from the Stars, The Science Fiction Stories of Walter M. Miller, Jr., The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr., The Darfsteller and Other Stories, and Dark Benediction. It has been translated into Croatian, Dutch, German, and Italian.

“Crucifixus Etiam” tells the story of Manue Nanti, a poor Peruvian who has signed an indenturement contract to work on Mars for five years. Nanti figures that with little to spend the money on while he’s working, he can save up and have a good sized nest egg when he returns to Earth. Shortly after his arrival, however, he realizes that conditions on Mars are not exactly as he had expected.

Prolonged exposure to the Martian atmosphere will retard his lungs’ ability, making it impossible for him to return to Earth. Disgusted by the workers who have succumbed, Nanti does everything in his power to retain his lungs’ strength. At the same time, he begins to question their purpose on Mars. Nanti’s plight is real as he tries to figure out how to be able to return to Earth and figure out what he is actually doing on Mars, not on an individual basis, but overall. He knows that the corporation isn’t being entirely truthful but nobody seems to know what is going on.

If the story has any weakness it is that Nanti’s epiphany comes suddenly, without any real evidence built up to allow the reader to understand what has caused his realization. Similarly, an action Nanti performs as the story comes to a climax seems to be without motive. Nevertheless, Miller portrays an intriguing corporate culture apparently set up to exploit the red planet’s natural resources.

Reprint reviewed in its the anthology A Science Fiction Century: 1950-1959, edited by Robert Silverberg, MJF Books, 1996.

Steven H Silver is a fifteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Big White Men—Attack!” in Little Green Men—Attack! Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 5 times as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7. He has been the news editor for SF Site since 2002.

Steven H Silver is a fifteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Big White Men—Attack!” in Little Green Men—Attack! Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 5 times as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7. He has been the news editor for SF Site since 2002.

I try to make notes for every story I read, and my note for this one concluded:

“This is a terrific story, sternly de-romanticising space exploration (rather like Edmond Hamilton’s “What’s It Like Out There?”) and offering instead a gritty, grimly realistic view of the hardships of the final frontier.”

It’s a refreshing reminder that not everything from the 50s is trite and dated!

This is an excellent story, belonging to a perhaps small category of stories that make us grateful for science fiction as something that speaks to our humanity as well as entertaining us and refreshing our sense of wonder.

“speaks to our humanity” is, perhaps, one of the hallmarks of Miller’s fiction.