Dune: Warts and All

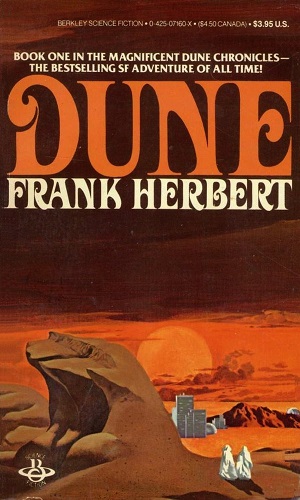

I read Frank Herbert’s Dune for the first time during university and loved it. It was pretty obvious why it had won the 1965 Hugo and Nebula awards. When I was in my late 30s, I went back to it, and couldn’t get through even a few chapters before the crash-and-burn. What happened?

I read Frank Herbert’s Dune for the first time during university and loved it. It was pretty obvious why it had won the 1965 Hugo and Nebula awards. When I was in my late 30s, I went back to it, and couldn’t get through even a few chapters before the crash-and-burn. What happened?

Bad writing to start with, mostly bad dialogue. The first bunch of chapters intercuts a lot between interesting things, like the Bene Gesserit and prescient memories, and Paul’s adventures, and cartoony super-villainy spouting Republic Serial Villain dialogue.

“Fools!”

“Those fools!”

“I’m going to get you!”

This execrable dialogue doesn’t even contain itself to the quotation marks. In-narrative close-third person dips into character’s thoughts spread the pain into the narrative and make George Lucas look like Hemingway.

We spend so much time with the villains in their self-congratulatory soliloquies at the beginning that I just stopped, scratching my head at how I could have enjoyed this.

Was I just a naive reading at 20, or had the style of writing changed so much between 1990 and 2010s that I’d gotten accustomed to different styles and aesthetics? I think probably it’s a bit of both.

But finally, in 2018, I finally tried again and pressed through and it turns out that after Paul and his mother are in the desert, the villains take a back seat. Then we get into the good stuff like the Fremen culture, some of the implications of the Bene Gesserit missionary work, the prescient memories as perceptions through time, and the sand worms.

This was the stuff I really enjoyed. Herbert took us through many of the implications of the scifi changes he made, and developed a really engrossing desert survival culture. Did this save the novel for me?

A bit. Maybe even more than a bit, given how much I enjoy science.

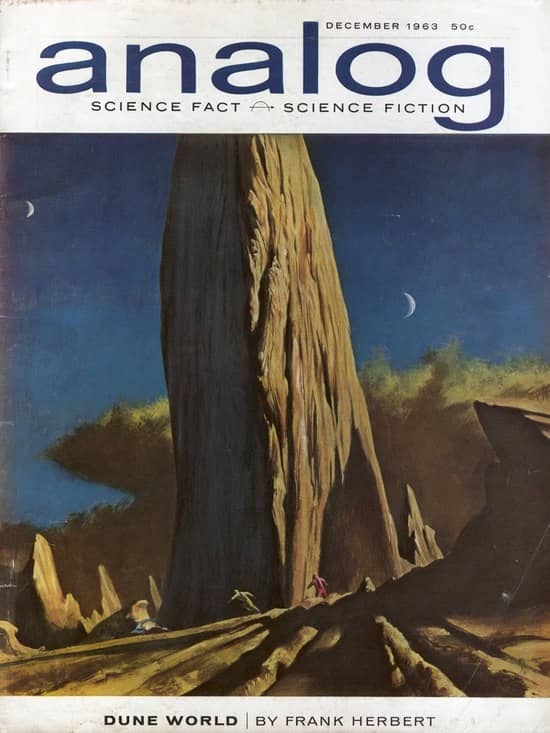

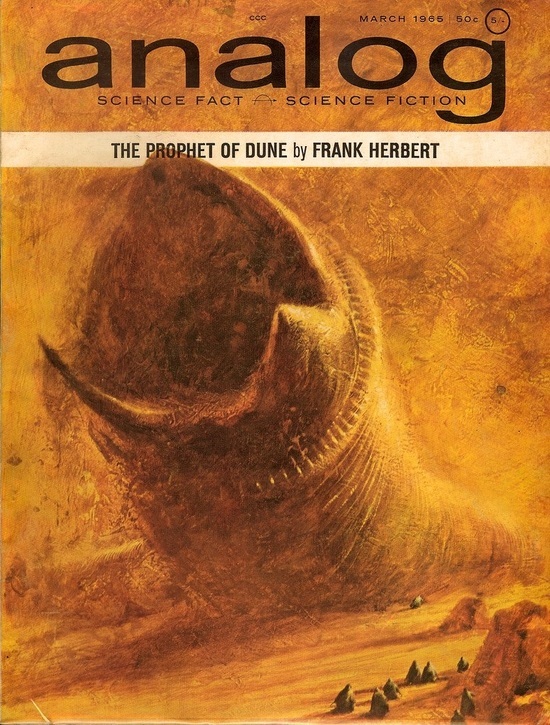

The original Analog Magazine cover of Dune

As a biologist, I loved the idea of the Bene Gesserit selecting of lines of humanity for traits. Herbert used the science available to him in the early 1960s. This was only 10 years after the discovery of DNA as the genetic molecule and still 10 years before the discovery of restriction enzymes that could be used to manipulate DNA.

The Hungry-Hungry Hippo of Space

At one point, one of the Bene Gesserits is worried that they’re going to lose both the Atreides and Harkonnen genetic lines in a knife fight, but of course, nowadays, we just need the DNA and we’ve already made entirely synthetic micro-organisms.

A couple of narrative choices still pulled down the ending for me.

The whole novel has a feeling of inevitability because of prescient memories and the just because at the 3/4 point in the book, while Paul and the Fremen are getting stronger, the villains kind of surrender.

They hunker into bases, suffer from overconfidence, and then for some bizarre reason, bring the emperor to Arrakis and land him on the ground where Paul can get him.

This ramping down rather than ramping up of the obstacles facing Paul sapped a lot of the urgency out of Act 3.

The other thing is just how much Paul is just a stand-in for male teenage wish fulfillment fantasies. Those fantasies have been at the core of SF since the late 1800s in pulps.

The style of “boy’s adventure” magazines feature teenagers who were underappreciated geniuses who in the end turned out to be better than everyone else at everything and got the girl. We’ve obviously (hopefully obviously) moved to an era with more kinds of stories and more sophisticated kinds of stories.

Paul Atreides is not only better than everyone at everything (the Bene Gesserit command voice, knife fighting, surviving, flying into a sand storm, etc), but he sees the future. Everyone talks about him.

He is the one in the prophecy. People make him their prince and king as soon as practicable. Women want him. And despite his wishes, greatness is thrust upon him.

Although a *lot* of my teenage reading followed this trope (Edgar Rice Burroughs, Katherine Kurtz, comic books, etc), it now just reads as not particularly original.

This is too bad, because many of the things that Herbert did in Dune do feel original, and when compared to the time he wrote it, sophisticated and advanced.

In the movie, Locutus of Borg assimilates the Fremen

I can still see why it got a Hugo and a Nebula, but I can also see why it’ll be decades before I reread it.

Derek Künsken writes science fiction and fantasy in Gatineau, Québec. He tweets from @derekkunsken. His first novel, The Quantum Magician, is serializing right now in Analog.

Dune is just one of those problem books for me. While I recognize its worldbuilding virtues and accept its status as a groundbreaking classic, I’m just unable to like it very much. Reading it was a real slog; there’s just something about Herbert’s prose style that makes it almost impossible for me to read him with enjoyment. (When I read Under Pressure, his novel of future submarine warfare, I would often reach the end of a paragraph or the end of a page, and realize that I had no idea what the hell Herbert had just said. Dune was better, but not completely…)

I’m sure the problem is as much mine as Herbert’s but life is too short, and there are soooo many other writers. Just two (space)ships that pass in the night, I guess…

For many years, Dune was one of my all-time favorites. I reread it about a dozen times or more. Then about 6 months ago I was rereading and was struck by the casual misogyny. The stuff about the bull’s head in the dining room, the way the Duke casually dismisses warnings about Harkonen plots because he assumed Jessica was the source of those warnings, etc.

Excellent article! (I’ll save my thoughts on the film and the mini-series for another time. 🙂 ) I’ve read Dune a few times, since first reading it in 1970. Decided to read it again last year after about 20 years. I couldn’t make it past the first 150 pages or so.