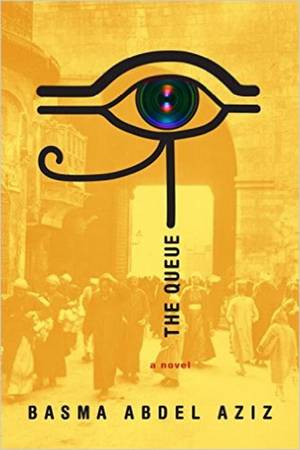

Egyptian Dystopian Fiction: The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz

Since the Arab Spring, there has been an upsurge in dystopian fiction coming out of the Middle East. The dashed hopes of that widespread popular uprising have found their expression in pessimistic novels such as Otared, (reviewed in an earlier post) and several other notable works of fiction.

Since the Arab Spring, there has been an upsurge in dystopian fiction coming out of the Middle East. The dashed hopes of that widespread popular uprising have found their expression in pessimistic novels such as Otared, (reviewed in an earlier post) and several other notable works of fiction.

One of the most lauded in the West is The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz, an Egyptian writer and social activist.

In The Queue, we are transported to a strange near future where the civilian government has been taken over by a faceless entity called the Gate. The Gate issues a series of edicts that become ever more baffling and hard to obey. Companies are forced to changed what they produce, individuals need to get signed forms for even the most mundane matters, and little by little the Gate forces its way into every aspect of the city’s life.

The people rebel, in what the Gate refers to as the Disgraceful Events, which are suppressed with predictable police brutality. One of the casualties is a young man named Yehya, who is shot by a police officer. Yehya needs a form signed in order to have the bullet removed, but the Gate closes right after the Disgraceful Events.

As Yehya languishes, the Gate issues a continuous torrent of edicts, prompting more and more citizens to line up in front of the Gate hoping to get their forms filled out. The line soon stretches for miles, developing its own economy and culture. Street preachers rail against the citizens for their lack of faith in the Gate, shopkeepers try to make a living selling tea and snacks to the other people in line, and salesmen give away free mobile phones that are bugged.

Yehya and his friends are desperate to get him permission for an operation, not only to save his life but to prove that the police shot at protestors. The Gate, of course, denies that the police opened fire and thus Yehya doesn’t have a bullet in him, and there is no need for any surgery.

From there it only gets more frustrating. The people are trapped in a nightmare world of red tape and doublespeak that made that time I tried to take on the IRS feel like a meditation session in a Zen monastery. At many points in the book I felt like slapping the characters and screaming, “Why don’t you organize a rebellion?”

But of course they couldn’t. Everyone in the queue had their own urgent reasons for being there. Everyone was terrified of losing their place or being refused the form they so desperately needed. They had been divided and conquered, and the endless barrage of propaganda from the media, now totally under the Gate’s thrall, as well as by the nation’s religious leaders, meant the people were too divided and brainwashed to ever hope to unify.

While the plot of The Queue was relentless and gripping, I found the prose style flat. There were too many declarative sentences, too many “He did this” and “She felt that”. This slowed me down and distracted me at times. I’m not sure if this is the fault of the author or the translator. Since translator Elisabeth Jaquette won the English PEN Translation Award for her work on this book, I’m thinking the fault may lie with the author. A Sudanese writer friend who I lent my copy to was also turned off by the style and decided to hunt down an Arabic copy. I’ll be interested to hear how the original holds up.

Despite this significant problem, The Queue is an important book for our time and I highly recommend it for anyone interested in the new wave of Arabic fiction.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page. His latest book, The Case of the Purloined Pyramid, is a neo-pulp detective novel set in Cairo in 1919. It comes out January 9.