War Eternal: Beyond the Farthest Star by Edgar Rice Burroughs

In 1940, Edgar Rice Burroughs created his final new adventure setting, the extrasolar planet Poloda. For the first time in a career that had ignited pulp science fiction back in 1912, Burroughs pushed beyond the solar system to the region of pure speculation. But what he discovered four hundred and fifty thousand light-years from Earth wasn’t an E. E. Smith space opera, or even an old-fashioned romp on a weird planet of monsters and savage humanoid tribes. Against the grain of its romanticized title, the incomplete short novel Beyond the Farthest Star isn’t an escapist tale, but a bleak meditation on a world mired in unending warfare. The title makes you anticipate Star Wars. Instead you find just Wars.

In 1940, Edgar Rice Burroughs created his final new adventure setting, the extrasolar planet Poloda. For the first time in a career that had ignited pulp science fiction back in 1912, Burroughs pushed beyond the solar system to the region of pure speculation. But what he discovered four hundred and fifty thousand light-years from Earth wasn’t an E. E. Smith space opera, or even an old-fashioned romp on a weird planet of monsters and savage humanoid tribes. Against the grain of its romanticized title, the incomplete short novel Beyond the Farthest Star isn’t an escapist tale, but a bleak meditation on a world mired in unending warfare. The title makes you anticipate Star Wars. Instead you find just Wars.

This is a stark work. It offers no illusions. There’s a dash of humor and some winking satire, but the overwhelming sensation of Beyond the Farthest Star is resignation to carnage. There are no valiant heroes on Poloda who become beacons for others to follow. There are only stalwart soldiers who fall in line to fight the fight, whatever it may be, and die in numbers tabulated by the hundreds of thousands.

We’re used to Edgar Rice Burroughs as a master of sweeping adventure in worlds where fighting means hope. It’s a shock to see him sitting glumly among the ruins of hope, waiting for the next wave of barbarians. Looking at Poloda from the perspective of the twenty-first century is to see a prophetic futurist emerging in Old Man Burroughs. The story the Old Man tells is not much fun. But it’s enthralling — and there’s nothing else like it in the ERB canon, even among the strange evolutions his work took during his last decade.

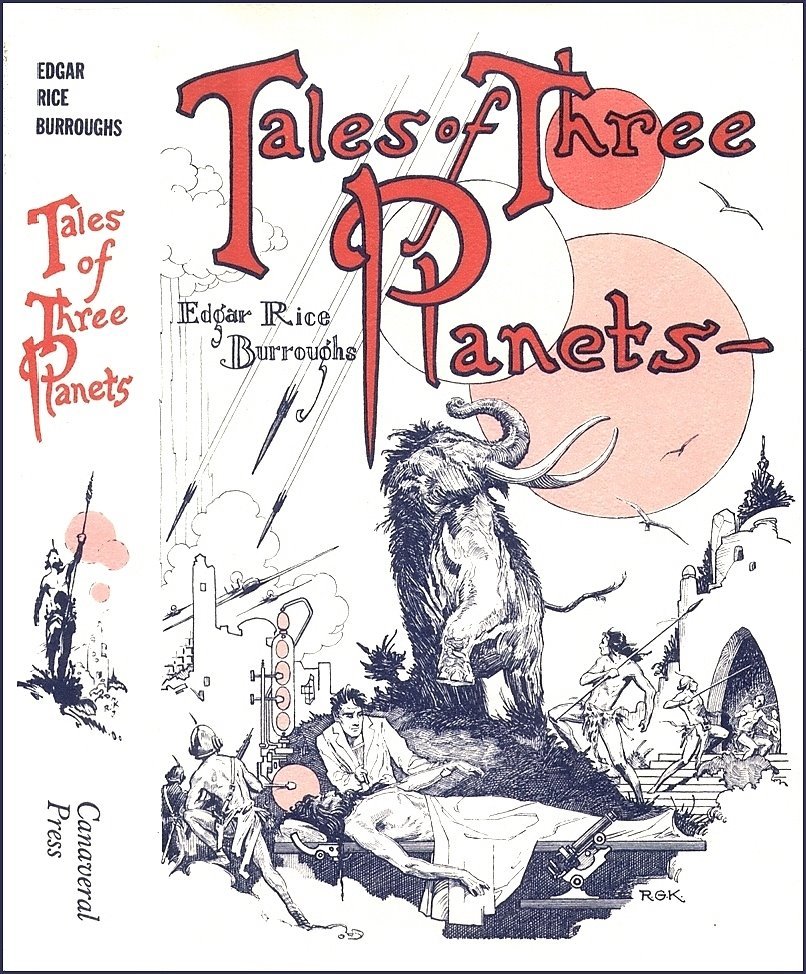

As with Savage Pellucidar and its sister books set on Mars and Venus, the Poloda novellas were planned to form a connected sequence for later hardcover publication. Part I, “Beyond the Farthest Star,” was written in October 1940 over twelve days, and Part II, “Tangor Returns,” was finished in December in five days. “Beyond the Farthest Star” appeared in the January 1942 issue of Blue Book, but Burroughs never submitted Part II for publication, probably because he scrapped the series after starting work as a war correspondent. “Tangor Returns” wasn’t discovered until thirteen years after Burroughs’s death. It was published along with “Beyond the Farthest Star” in the 1964 Canaveral Press omnibus Tales from Three Planets. Ace Books later released a paperback of the unfinished Poloda saga as Beyond the Farthest Star, with the first novella retitled “Adventure on Poloda.”

Burroughs created extensive background notes on Poloda, its continents and cities, and the surrounding star system of eleven planets. He corresponded with Professor J. S. Donaghho in Honolulu to add scientific verisimilitude to his first trip outside the solar system. But advanced science-fiction concepts play only minor parts in the finished Poloda stories. Most of the science was tossed onto the flaming pyre of the realities of modern combat.

War was a major feature of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s work from the start, and he never shied from describing it as brutal and bloody. The violence of the Thark warrior culture in A Princess of Mars does nothing to sweeten what happens in battle, and the World War I fighting in Tarzan the Untamed (1920) is still a visceral shock as Tarzan massacres his way through German lines in the East African theater. Yet there’s a romantic soul to war in these earlier works; combat is a noble calling where a single brave fighter can make a difference, and where victory brings rewards such as the love of a princess or the unification of races.

War was a major feature of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s work from the start, and he never shied from describing it as brutal and bloody. The violence of the Thark warrior culture in A Princess of Mars does nothing to sweeten what happens in battle, and the World War I fighting in Tarzan the Untamed (1920) is still a visceral shock as Tarzan massacres his way through German lines in the East African theater. Yet there’s a romantic soul to war in these earlier works; combat is a noble calling where a single brave fighter can make a difference, and where victory brings rewards such as the love of a princess or the unification of races.

But even before the U.S. entered World War II, Burroughs’s writing about warfare underwent a transformation. Older and fatigued by personal struggles, ERB sloughed off the glory and romance of combat and turned fatalistic and embittered. He still viewed participation in war as a patriotic necessity — he volunteered for civilian duty the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor — but his later writing bleaches away the heroism of war and portrays it as an endless cycle that grinds the human spirit to nothing except morbid resolve. People don’t fight for goals. They fight because they have nothing else.

Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”, set in the Pacific theater of World War II, is the most violent example of Burroughs’s change in attitude toward war. But the invented war on a fictional planet in Beyond the Farthest Star gave him the freedom to examine warfare as all-eclipsing and eternal. On Poloda, where armed conflict between the nations of Unis and Kapara has lasted for a hundred and one years, warfare is the consuming fact of life. Although Kapara is the oppressive and cruel country of the two, something made clearer in the second half, the war isn’t cast as good against evil. The focus is on the war’s consequences for the world and its inhabitants. Cities across five continents have been leveled. Losing a thousand ships in a single battle and a hundred thousand people in a month is expected. Clothing, vehicles, and homes all look identical because production is streamlined to favor war. Religion has almost gone extinct because no one has time for anything else away from fighting, preparing to fight, or recovering from fighting. You can’t be a pacifist on Poloda, but there are no glorious rewards for doing your duty either. (Certainly not the hand of a princess.) You’ll likely end up another number among the millions of dead, replaced by a nation’s best defense against non-stop casualties: a high birth-rate. Even the ostensible hero of the story baldly states, “There is no chivalry in complete war.”

The “hero” of Beyond the Farthest Star is, appropriately, an unnamed soldier. At the moment of his death in our world, his body filled with bullets from a German Messerschmitt as his plane dives to the ground, he zaps across the light-years from Earth to Poloda. There he receives the name “Tangor,” which means “from nothing,” and joins the forces of Unis in their ceaseless fight against Kapara.

Tangor’s instantaneous travel from Earth to Poloda has a metaphysical aspect. Tangor doesn’t know if he died on Earth when the Germans shot him down. He leans toward believing his existence on Poloda is the afterlife. The unnamed man ponders if death means the relocation of the spirit to another place in the vast universe. Poloda is his destination after death, but each man or woman may have their own otherworld port of call after their “transition” (as Tangor calls it). This adds an additional layer of fatalism to the story: a pilot caught in warfare on one planet is freed from that life only to resurrect in the middle of a larger war that has no end. Literally no end, since Burroughs didn’t live to conclude Tangor’s story.

“It is war.” This is the mantra of the people of Unis. Tangor learns that warfare “governed their every activity, their every thought. From birth to death they knew nothing but war. Their every activity was directed at their one purpose of making their country more fit for war.” They don’t even know what they would do with themselves if there were no war. Their population is large enough to reproduce at a rate to keep constant with the staggering casualties. They don’t use bomb shelters to protect themselves; their cities are bomb shelters that lower into the ground during each Kapar bombing run.

“It is war.” This is the mantra of the people of Unis. Tangor learns that warfare “governed their every activity, their every thought. From birth to death they knew nothing but war. Their every activity was directed at their one purpose of making their country more fit for war.” They don’t even know what they would do with themselves if there were no war. Their population is large enough to reproduce at a rate to keep constant with the staggering casualties. They don’t use bomb shelters to protect themselves; their cities are bomb shelters that lower into the ground during each Kapar bombing run.

The elevator cities of Unis are one of the few bits of science-fiction technology in the novel, which otherwise is low-tech enough to feel like a dystopian version of Earth a few decades in the future. Heavier-than-air craft fire bullets at each other in dogfights only a generation removed from the combat of the 1940s. When Tangor describes the mental state of the Unisans as “a world in hiding” where everyone thinks of weaving and dodging bombs whenever they’re outside, he might be a reporter during the London Blitz contemplating the future state of Britain.

A break in the war fatalism arrives in a surprising moment at the end of Part I. The wife of Tangor’s closest ally, psychiatrist Harkas Yen, goes into a harangue against the principal tool of warfare, the plane. Read this passage and remember that aerial adventures were one of the exciting horizons of the pulp magazines in the ‘teens and twenties:

Planes! The curse of the world. History tells us that when they were first perfected and men first flew in the air over Poloda, there was great rejoicing, and the men who perfected them were heaped with honors… Through them civilization was to be advanced hundreds of years; and what have they done? They have blasted civilization from nine-tenths of Poloda and stopped the advance in the other tenth. They have destroyed a hundred thousand cities and millions of people, and they have driven those who have survived underground, to live the lives of burrowing rodents. Planes! The curse of all times. I hate them. They have taken thirteen of my sons, and now they have taken my daughter.

Her husband interjects with the refrain, “It is war.” She retorts, “No, this is not war — it is rapine and murder.” This open sore of a moment doesn’t last long; the first part of the book concludes with the icy statement: “Listen! The sirens are sounding the general alarm.” The slaughter continues.

Part II shifts into an espionage story. The Unis Commissioner of War assigns Tangor the task of locating a Kapar power amplifier that may allow flight to other planets. Tangor pretends to be a traitor to Unis and travels to Kapara along with an actual traitor, the woman Morga Sagra. After the almost plotless first half, this premise sounds like a basis for a standard pulp thriller. But Burroughs still doesn’t allow the story to turn toward lighter adventure. As soon as Tangor arrives in Kapara, his mission collapses when the secret police capture him and dump him into a gulag.

There’s no pulp action in Part II, but “Tangor Returns” generates suspense because the protagonist is trapped in a setting of constant surveillance and paranoia. Tangor gives readers a street-level look at life in the Stalinist society of Kapara. There are shades of the satire on fascism Burroughs used in Carson of Venus, but the analogy is less broad and with little humorous commentary, making it more frightening. Kapar society is grotesque and scary, and there’s nothing Tangor can do to fight against it. He cannot rescue his one ally, the decent man Horthal Wend, whose own son turns him over to the Zabo, the Kapar secret police. Horthal Wend vanishes, and Tangor never sees him again — similar to the political vanishings happening every day in Europe at the time. Tangor escapes at the end of Part II with no heroic flourish. He retrieves the power amplifier, but it’s not a weapon that can turn the tide of war in favor of Unis. It’s a tool for the Unisans to leave their ruined planet and find peace on another world. It’s the only option that makes sense on hero-less Poloda.

Tangor is a remarkable protagonist for an ERB novel because he is unremarkable. Burroughs had attempted a more realistic main character with Carson Napier in the Venus series, but Napier was noteworthy less for realism than for his incompetence. Tangor, the Man from Nothing, is Carson Napier done right. He’s a hero only in the sense of his bravery. He possesses no superlative skills to rank him above the Polodians. He can’t even get into the flying service at first, but instead serves in the Labor Corps that handles the job of quickly relandscaped bombed areas to keep morale up and make the enemy feel their attacks have been futile. When he does get his chance to fly, Tangor only downs three enemy planes in his first engagement before he’s shot down. When Tangor fails, he fails like a normal person.

Tangor is a remarkable protagonist for an ERB novel because he is unremarkable. Burroughs had attempted a more realistic main character with Carson Napier in the Venus series, but Napier was noteworthy less for realism than for his incompetence. Tangor, the Man from Nothing, is Carson Napier done right. He’s a hero only in the sense of his bravery. He possesses no superlative skills to rank him above the Polodians. He can’t even get into the flying service at first, but instead serves in the Labor Corps that handles the job of quickly relandscaped bombed areas to keep morale up and make the enemy feel their attacks have been futile. When he does get his chance to fly, Tangor only downs three enemy planes in his first engagement before he’s shot down. When Tangor fails, he fails like a normal person.

Tangor doesn’t even have a love interest. This is a sharp but refreshing difference between Beyond the Farthest Star and the rest of Burroughs’s work. It shows how much the author was willing to break his own mold for a new type of war tale. When Tangor first arrives naked on Poloda, a girl spots him and runs away. Readers familiar with Burroughs will mark this girl as Tangor’s future love interest, since his heroes often fall for the first woman they meet in their adventures. But the girl, Balzo Maro, is a minor character with limited interaction with Tangor after the first chapters. Tangor develops a girlfriend at the start of Part II, Morga Sagra. This isn’t a romance, however, but a way to get into the espionage story when Morga Sagre defects to the Kapars. Tangor has no deep feelings for her, and her fate is to die under torture after informing on Tangor to the Kapar secret police. The only indication of genuine romance appears in the final paragraphs: Tangor shares a kiss with Yamoda, the daughter of Harkas Yen, a woman he previously thought of in a sisterly fashion, before he leaves on a hopeless mission.

The prologues to Parts I and II are short but say a great deal about Edgar Rice Burroughs’s life at the time. There’s little difference between the real ERB and the fictional one who narrates the adventures his characters send to him. Both now live in Honolulu, wondering where their waistlines went. After a night hearing stories about ancient Hawaiian superstitions at a party on Diamond Head, the pseudo-ERB returns home to think about finishing a new story when an invisible force begins to press down his typewriter keys. This ghostly writing produces the two manuscripts of the man called Tangor. It’s a gentle jab at the idea of authors who are supposedly so inspired that their stories simply “write themselves.” I have to imagine that in his old age Burroughs occasionally wished this were true.

“Tangor Returns” (and therefore all of Beyond the Farthest Star) closes with a note from the pseudo-ERB — referring to himself as “The Editor” — that he never learned anything further about Tangor. No more phantom typists visited to tell whether Tangor reached the planet Tonos or if the people of Unis succeeded in their plan of escape to a new world. Based on the pessimism of Beyond the Farthest Star, my guess for where the novel might have gone is Tangor discovering that Tonos is unsuitable for resettlement, then returning to Poloda to tell the Unisans they must fight to the last against the Kapars. Like both the real and the fictional ERB, I’ll never know for certain.

And so the war on Poloda remains the Eternal War. It’s fitting. The unfinished work may have more to say than if it struggled to reach the type of conclusion Edgar Rice Burroughs no longer believed in.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

A great post that echoes my feelings pretty closely. People simply don’t give ERB enough credit. I’d love to see your take on “Pirate Blood” as well.

BTW, it just struck me that the Krenkel illo above might be a nod from RGK to Franklin Booth. It has that feel to me.

This one I’ve only read once, and I didn’t remember much about it; back onto the TBR pile it goes.

Am I the only one who, as you described the set-up (planet riven by total, constant war) imagined the Starship Enterprise arriving to Teach Them the Error of Their Ways?

@Joe H. – I can see it…

KIRK: Don’t you realize that this endless war, it can only bring you grief, no lesson, no healing?

HARKAS YEN: It is war.

SPOCK: The repetition of this phrase does not constitute an argument.

HARKAS YEN: You have not lived here. You have not seen the skies filled with the ships of Kapara, killing our sons, daughters, wives, brothers, husbands. You have not see how we fight back, every day, against them.

SPOCK: I need not witness the carnage of warfare to understand its effect on the mind. I would ask you to look with a logical eye at your own statement.

KIRK: Listen, we’re trying to stop those deaths. It doesn’t have to be this way.

BONES: Jim, you’re not getting through. And this Vulcan won’t succeed at getting through to them either. He’s just as mad as people were in 20th century when it came to war.

SPOCK: The doctor is, in his blunt manner, accurate regarding the obstinacy of these people.

BONES: For once Spock, I won’t look for the insult in that statement.

SPOCK: You will find none, doctor.

HARKAS YEN: Listen! The sirens are calling! Help us fight or stay and die—it matters not to me.

That’s some impressive Star Trek! Thoroughly entertained. ?

Ryan knows his Trek! Sounded like he was channeling the characters just right!

I have finished listening to the audiobook version of the restored edition published by ERB Inc.

This is indeed one of ERB’s and it’s ” Incomplete status” does not diminish it. The grim mood of the Unisans is what makes this story work as well as Tangor being a great hero