Peplum Populist: The Last Days of Pompeii (1959)

In August of the first year of the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, the volcano Vesuvius erupted in the south of Italy and destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Thousands of lives were lost. Out of the fire, ashes, and pyroclastic flows, an Italian film subgenre was born.

In August of the first year of the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, the volcano Vesuvius erupted in the south of Italy and destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Thousands of lives were lost. Out of the fire, ashes, and pyroclastic flows, an Italian film subgenre was born.

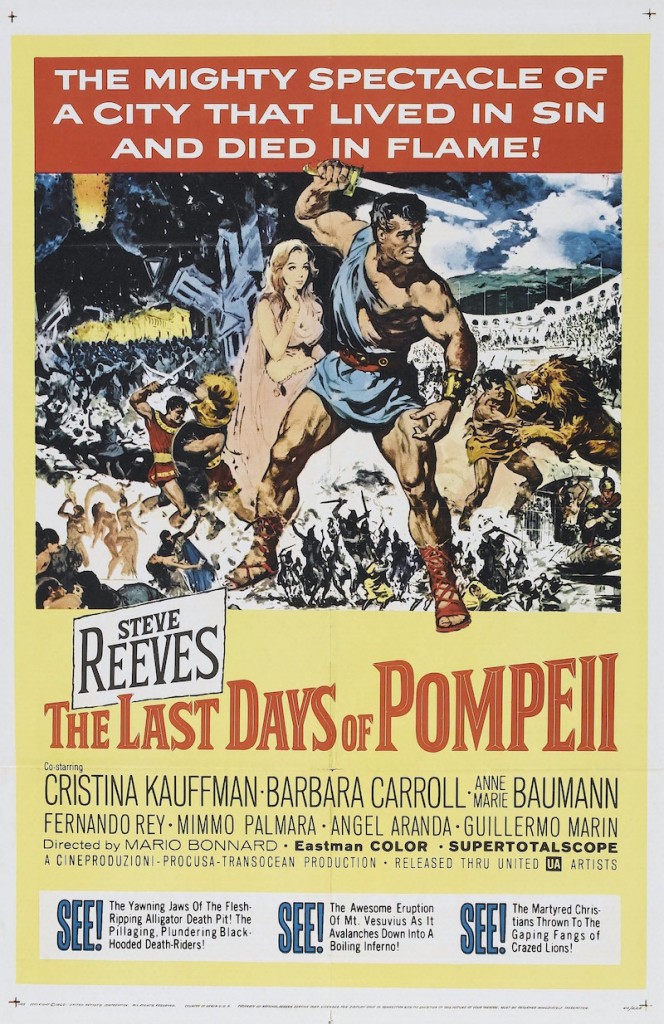

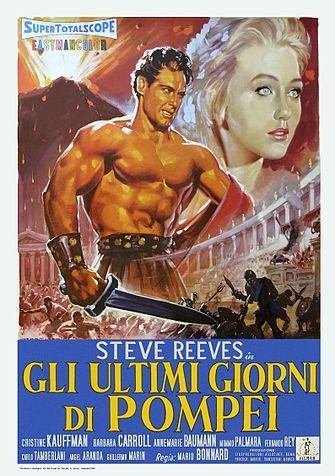

The 1959 film The Last Days of Pompeii (Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei) is the most famous of the many journeys Italian cinema has taken into the story of Vesuvius’s first-century eruption. Ostensibly based on Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s bestselling 1834 novel, the movie is a sword-and-sandal (peplum) riff that departs freely from its source so it can work as a vehicle for new megastar Steve “Hercules” Reeves. Reeves was at the height of his stardom and the peplum genre was also approaching the summit of its commercial success. There were loopier and cheesier days ahead for sword-and-sandal movies — I would argue more fun days — but for class and cash, The Last Days of Pompeii is a pinnacle. It lumbers sometimes under the weight of trying to appear like a serious prestige picture, but the lust for action entertainment carries it along. If you want to watch a dead serious epic from the same year, you have Ben-Hur. If you want to watch masses of polystyrene walls and pillars rain down on the cast and a hero slay lions and crocodiles, stay here.

Mario Bonnard is credited with directing The Last Days of Pompeii, but he fell sick on the first day of production. The man who took over the job was the assistant director, Sergio Leone. Yes, that Sergio Leone. Leone already had extensive experience working on Hollywood epics shot in Rome, including Quo Vadis. He proved he could helm a big feature with The Last Days of Pompeii, and soon after landed his first credited director job on another peplum, the fantastic romp The Colossus of Rhodes (1961), which I humbly submit is the pest peplum of all time. Two years later, Leone jump-started the genre that would surpass sword-and-sandal movies as the Next Big Thing in Italy with his Western, A Fistful of Dollars.

Although the eruption of Vesuvius is the reason the film was made, its story works as an ancient Roman drama even without the volcano. This isn’t a modern disaster film where the volcano is a constant subject of speculation with the actual on-screen disaster consuming the entire last third. Vesuvius appears in a few matte paintings and receives almost no mention again until the last ten minutes, when it interrupts the finale in the amphitheater to become the big curtain-closer. Forget the former plot, everybody run away!

The non-volcanic part of the story centers on a conspiracy of Pompeii’s Egyptian priests of Isis to steal the wealth of the city’s aristocrats to raise an army to free Egypt from Roman control. The bandits leave behind the mark of the cross at their robberies to frame the local Christian population. The secret leader of the Isis cult is Julia (Anne-Marie Baumann), Egyptian mistress to Consul Ascanius (Guillermo Marín), who is easily manipulated into taking action against the Christians to prevent the displeasure of the emperor. The centurion Glaucus Leto (Reeves) becomes tangled in these affairs when his father dies in one of the raids. Glaucus plots revenge against the murderers, but later discovers the deception of Egyptians and sides with the Christians, which also pits him against the Roman hierarchy. Glaucus falls for Ascanius’s daughter Ione (Christina Kaufmann), who converts to Christianity through the example set by her blind servant Nydia (Barbara Carroll).

This story and characters are only tangentially related to those of Bulwer-Lytton’s novel, with significant changes made to Glaucus and Julia to create a slimmer, action-focused narrative. This is a religious epic where a hero with a sword can swoop in to fight off lions about to eat Christians and where the villain has a trapdoor in his sinister temple that plunges people into a crocodile pit. We’re also treated to Glaucus in a muscular tangle with a treacherous Praetorian guard (Mimmo Palamara, who was in both of Reeves’s Hercules movies) and a furious battle with gladiator-assassins in the amphitheater. It’s conventional peplum action, but most of it is excellently shot and choreographed (the crocodile scene is a bit tatty) and are the best stretches of the film not involving a volcano.

The Last Days of Pompeii ‘59 is the rare Italian peplum with the persecution of Christians as a major part of the story. Hollywood epics like Quo Vadis, The Robe, and Ben-Hur use biblical themes and Christian redemption as an emotional and spiritual backbone for their spectacle. Italian peplum films are pulpier and rarely dip into contemporary religious ideas, preferring loose readings of Greek myths for simple good-vs-evil adventures. The Last Days of Pompeii’s mixture of peplum thrills and religious drama is a rocky one. The filmmakers show little dramatic interest in religious themes or emphasizing Christian moral superiority over pagan decadence. The gentle Nydia and her relationship with a thief (Angel Aranda) has the most spiritual feeling to it, but it’s a lesser subplot. The main story doesn’t go much deeper than a brawny hero defeating corrupt foreign cultists — which describes 75% of sword-and-sandal films. Ione’s conversion to Christianity is done flippantly to the point you almost miss when she converted. Glaucus never investigates the religious beliefs of either the Christians or Isis-worshippers; he only wants to ensure he directs his revenge against the right villains.

The Last Days of Pompeii ‘59 is the rare Italian peplum with the persecution of Christians as a major part of the story. Hollywood epics like Quo Vadis, The Robe, and Ben-Hur use biblical themes and Christian redemption as an emotional and spiritual backbone for their spectacle. Italian peplum films are pulpier and rarely dip into contemporary religious ideas, preferring loose readings of Greek myths for simple good-vs-evil adventures. The Last Days of Pompeii’s mixture of peplum thrills and religious drama is a rocky one. The filmmakers show little dramatic interest in religious themes or emphasizing Christian moral superiority over pagan decadence. The gentle Nydia and her relationship with a thief (Angel Aranda) has the most spiritual feeling to it, but it’s a lesser subplot. The main story doesn’t go much deeper than a brawny hero defeating corrupt foreign cultists — which describes 75% of sword-and-sandal films. Ione’s conversion to Christianity is done flippantly to the point you almost miss when she converted. Glaucus never investigates the religious beliefs of either the Christians or Isis-worshippers; he only wants to ensure he directs his revenge against the right villains.

Even the concept of Vesuvius raining down punishment on the wicked is sketchily developed. The volcano isn’t divine retribution or a moral lesson; it’s spectacle to send the audience out of the theater jazzed up. By the time of the eruption, the movie is deep into an arena uprising where the religious sides hardly matter.

(By the way, I’m unimpressed with Pompeii’s lions-eating-Christians program. Sending one lion into an arena with around three dozen Christians is going to result in the show running overlong. I hope there’s a Jumbotron screen to pacify the bloodthirsty crowd with trivia questions and bloopers from gladiator duels while the lion takes three months to eat everyone.)

The eruption of Vesuvius is the predestined fate of the movie and the one money-eating set-piece the filmmakers had to get right. The production didn’t have the resources to dump twenty feet of ash onto Pompeii, so the destruction is closer to what you might see in a movie about an earthquake, but with the addition of sparks raining down on fleeing citizens. Walls tumble, support beams crash, statues of deities ironically crush evil priests, smoke clogs up the frame, and a surprising number of our heroes make it to boats before the FINE title card appears. It isn’t the scope of a Hollywood film, but there’s an edge of danger to this spectacle in an Italian film — the fear a stunt performer or extra is going to get seriously hurt among the mass of pyrotechnics and crashing scenery.

It’s best not to look at The Last Days of Pompeii as a “Sergio Leone Film.” You won’t find grubby close-ups or elegantly orchestrated long takes full of ritualized tics. His direction is colorful and exciting, but it adheres to the peplum rulebook established by 1959 and delivers what the investors wanted: a movie resembling Quo Vadis at a third the price. Sword-and-sandal films would get nuttier after this, while Leone went off to write the rulebook for his own subgenre.

For the record, another future Italian Western master had a prominent role on The Last Days of Pompeii: Sergio Corbucci (Django, The Great Silence) is credited as a co-writer and assistant director. Corbucci got his turn directing a Steve Reeves sword-and-sandal film in 1962 with The Slave, a.k.a. The Son of Spartacus.

For the record, another future Italian Western master had a prominent role on The Last Days of Pompeii: Sergio Corbucci (Django, The Great Silence) is credited as a co-writer and assistant director. Corbucci got his turn directing a Steve Reeves sword-and-sandal film in 1962 with The Slave, a.k.a. The Son of Spartacus.

If any participant in The Last Days of Pompeii deserves to receive authorial credit, it’s the star. This is Steve Reeves’s The Last Days of Pompeii. The European version of the Hollywood historical epic grew up around the American bodybuilder, and the story of the novel was specifically rejiggered to fit his presence and what audiences expected from a “Steve Reeves film.”

Steve Reeves is one of the most underrated action leads in movie history. Even though he was once one of the top box-office draws in the world and opened the way for the muscular action heroes of later decades, he’s mostly vanished from the history books. And Reeves was actually good. He’s definitely the best of the many peplum musclemen actors, with a combination of Hollywood handsomeness and granite-jawed tenacity that made him an imposing screen presence. He always showed complete commitment to his parts, and the English dubbing matched him with voice actors who could pave over Reeve’s acting inexperience.

Reeves tended to shine brightest when paired with skilled actresses. The Last Days of Pompeii fumbles a bit in this respect. Glaucus’s love interest, Ione, is played by Austrian actress Christina Kaufmann, who was only fourteen at the time and looks it. The filmmakers may have truncated the Glaucus/Ione love story to only a few scenes to avoid the awkward age difference between the actors. The “evil queen” character of Julia, played by Anne-Marie Baumann, has more time with Glaucus, but it isn’t a steamy seduction of the kind found in Hercules and Maciste films. I like what Baumann does as Julia, especially when she gives her “Why I Am Evil” speech before murdering Ascanius. But not tying her closer to Glaucus for romantic tension was a missed opportunity.

The Last Days of Pompeii was the peak of Reeves’s career, although for an unfortunate reason. He dislocated his shoulder during a stunt sequence when his chariot collided with a tree. The injury worsened during the shooting of the crocodile fight. This marked the beginning of the end of Reeves as an action star. Although he continued to act in Italian movies until 1963, the increasing pain from the injury led to his early retirement. He tried a comeback in 1968 with the Western A Long Ride from Hell. The film was a box-office disappointment, and Reeves permanently quit acting. He used his money to buy a ranch in California where he bred horses. He died in 2000, the same year Gladiator was released — a film that owes much to The Last Days of Pompeii and Reeves. Although I’m on record as a big fan of Gladiator, these days I prefer watching Steve Reeves and his successors beat up helmeted goons and papier-mâché monsters in barely controlled Italian films. Or even a more-or-less controlled Italian film like The Last Days of Pompeii.

All this Sergio Leone talk makes me think I should look at The Colossus of Rhodes next. However, there’s another Vesuvius film streaming on Amazon Prime, 1962’s AD 79: The Destruction of Herculaneum. Same volcano, same date, different town, lower budget, director of Sabata, and Brad Harris. Might be interesting. Not the Brad Harris part, though.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

If this great essay were a movie, it would have been filmed in SUPER TOTALSCOPE. Thanks for it, and the others in this series.