Grimmer Than Grim: The Children of Húrin by J.R.R. Tolkien

…since you are my son and the days are grim, I will not speak softly: you may die on that road.

Morwen to her son Húrin

One of the most significant elements of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings — and missing from Peter Jackson’s misdirected films — is the almost suffocating atmosphere of great melancholy over a lost, better world; lost due to pride and jealousy. Even in the The Hobbit, a book aimed more at children than adults, it pervades the story, one that depicts the actions of pitiably small individuals against a world that, outside the green confines of Bilbo’s Shire, is dangerous and long bereft of the comforts and protections of civilization and order. It rises in The Lord of the Rings from a mournful undercurrent to a major theme. The characters cross a landscape littered with the ruins and remnants, such as the remains of Amon Sul and the titanic Argonath, of a nearly forgotten past. The once mighty elf realms, even Lothlorien, are reduced to dying shadows of what they were. The towering city of Minas Tirith is crumbling and half-empty.

One of the most significant elements of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings — and missing from Peter Jackson’s misdirected films — is the almost suffocating atmosphere of great melancholy over a lost, better world; lost due to pride and jealousy. Even in the The Hobbit, a book aimed more at children than adults, it pervades the story, one that depicts the actions of pitiably small individuals against a world that, outside the green confines of Bilbo’s Shire, is dangerous and long bereft of the comforts and protections of civilization and order. It rises in The Lord of the Rings from a mournful undercurrent to a major theme. The characters cross a landscape littered with the ruins and remnants, such as the remains of Amon Sul and the titanic Argonath, of a nearly forgotten past. The once mighty elf realms, even Lothlorien, are reduced to dying shadows of what they were. The towering city of Minas Tirith is crumbling and half-empty.

It’s in the under-read The Silmarillion, Tolkien’s complex sequence of Middle-earth myths and legends, that he fully explores the litany of misbegotten oaths, pride-blinded decisions, betrayals, murders, rapes, and invasions that led to the downfall and destruction of the old world. And between two tales, those of the war of the house of Fëanor and Morgoth and the sinking of Númenor, we learn of the ruination directly underlying the events chronicled in The Lord of the Rings.

One of the worst tragedies told in The Silmarillion is that of doom laid on the family of Húrin Thalion, and specifically the fate of his son Túrin Turambar and daughter Niënor Níniel. Inspired by the Finnish story of Kullervo (a story Tolkien turned his own hand to, released in 2015 and discussed here), Túrin’s fate mimics his but is tied to a greater story that concerns not just his own family but all Middle-earth.

The Children of Húrin (2007) is a standalone expansion of that story, and takes place in the final stages of Morgoth’s (essentially Satan’s) war on the Elves and their human allies. Following their great defeat in the battle of the Dagor Bragollach, the Battle of Sudden Fire, the elves and their allies have spent twenty years rebuilding their forces in order to launch a direct attack on Morgoth’s great fortress, Angband. It is during these preparations that the book opens.

As he readies himself for a battle he has doubts about, Húrin tells his wife, Morwen, that should the Enemy prevail, their son Túrin should be sent to safety in the elven kingdom of Doriath. Húrin’s worries prove well-grounded, and even more disastrously than in the previous battle, the Elves and their allied forces are destroyed. This second great battle is called the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. Most of the generals are killed, and the few survivors are driven into hiding as their lands are overrun by orcs and men allied to Morgoth.

Húrin, who with his brother Huor allows the escape of the great elf lord, Turgon, is taken prisoner. As punishment for his defiance, Morgoth lays a curse on Húrin’s house:

I am the Elder King: Melkor, first and mightiest of all the Valar, who was before the world, and made it. The shadow of my purpose lies upon Arda, and all that is in it bends slowly and surely to my will. But upon all whom you love my thought shall weigh as a cloud of Doom, and it shall bring them down into darkness and despair. Wherever they go, evil shall arise. Whenever they speak, their words shall bring ill counsel. Whatsoever they do shall turn against them. They shall die without hope, cursing both life and death.

Morgoth then straps Húrin to a chair high on a mountain, and grants him the power to see all the evils that befall his family wherever they take place.

Túrin is sent south to Doriath by his mother. There he is trained in all the arts of war and survival in the wilderness. He becomes a great hero for his actions against the orcs. But a misunderstanding, caused by the death of an elf jealous of Túrin’s good treatment, leads to the latter’s exile.

Once gone from Doriath, Túrin begins a steady descent toward his eventual doom. He joins a band of outlaws, men driven from their homes in the wake of the Nirnaeth Arnoediad. Eventually he assumes command of the outlaws and draws all the other surviving Elves and allied Men to him. When Morgoth learns the bandit leader is not some nameless warrior, but Húrin’s son, he sends forces to capture him. This leads directly to not only his capture, but the deaths of most of the outlaws, and that of his friend, Beleg.

Following his escape, Túrin ends up in another of the surviving elf kingdoms, Nargothrond. His arrival spells doom for that kingdom. By the force of his personality he is able to convince the elven king, Orodreth, to reject the warning of one of one of the divine Valar, and instead plan to take an aggressive stance against Morgoth and his armies. This opens the kingdom to a black fate and it is destroyed, most of the elves killed, and most of the survivors enslaved. Glaurung, the first of the dragons created by Morgoth, takes the underground city of Nargothrond for his lair.

There are more trials and battles in Túrin’s life before his final doom is played out. Unbeknownst to him, his sister Niënor is drawn directly into the maelstrom of fate swirling around him. Before the tale is through, both are utterly devastated by Morgoth’s curse.

The Children of Húrin is a story of obsession and the ruin it brings to someone tainted by it. Morgoth’s curse is potent, and it leads him to sending his forces to explicitly deter and defeat Túrin. Most of the time, though, Túrin’s failings arise from his own desire to avenge his father’s presumed death and the destruction of his homeland. The downfall of Nargothrond lies directly at his feet. His self-centeredness and quickness to anger also help bring about his doom far more than any clear action of Morgoth. We can feel his downfall drawing ever closer, every misstep he makes, and, of course, are completely unable to direct him away from his fate. Instead we are forced, like his father, to remain in our seats and watch Túrin spiral closer and closer to his end.

Over the years, the stories of J.R.R. Tolkien have been variously criticized as sentimental, odes to conservative attitudes on religion and politics, or even immature. The essays linked here are by eminent authors of fantasy themselves. While I am in disagreement with them all, I recommend them to any Tolkien reader. I bring up these criticisms only to note that this book is assuredly none of those things. Those of Húrin’s people who survive the Battle of Unnumbered Tears are reduced to thralldom by their new overlords, the Easterlings, men allied to Morgoth. Instead of becoming some sort of noble resistance, many of the survivors turn to banditry, preying on their own people as readily as on the Easterlings. Many of the elven characters, dismissed as “natural aristos” by one critic, are neither noble nor good-natured, but petty and spiteful. Violence and gray morality don’t necessarily make a story more mature, often being just slathered on to make a story more “realistic.” That is not the case here. The Children of Húrin is a darker book than much of what’s current, and the violence, written by a man who survived the Battle of the Somme, and perforce knew what real war and sudden death were like, feels more realistic and appropriate than in many other fantasy novels. Without succumbing to the modern penchant for explicit gore, this is a book streaked with blood and filled with violent death of the guilty, innocent, and indifferent alike.

Over the years, the stories of J.R.R. Tolkien have been variously criticized as sentimental, odes to conservative attitudes on religion and politics, or even immature. The essays linked here are by eminent authors of fantasy themselves. While I am in disagreement with them all, I recommend them to any Tolkien reader. I bring up these criticisms only to note that this book is assuredly none of those things. Those of Húrin’s people who survive the Battle of Unnumbered Tears are reduced to thralldom by their new overlords, the Easterlings, men allied to Morgoth. Instead of becoming some sort of noble resistance, many of the survivors turn to banditry, preying on their own people as readily as on the Easterlings. Many of the elven characters, dismissed as “natural aristos” by one critic, are neither noble nor good-natured, but petty and spiteful. Violence and gray morality don’t necessarily make a story more mature, often being just slathered on to make a story more “realistic.” That is not the case here. The Children of Húrin is a darker book than much of what’s current, and the violence, written by a man who survived the Battle of the Somme, and perforce knew what real war and sudden death were like, feels more realistic and appropriate than in many other fantasy novels. Without succumbing to the modern penchant for explicit gore, this is a book streaked with blood and filled with violent death of the guilty, innocent, and indifferent alike.

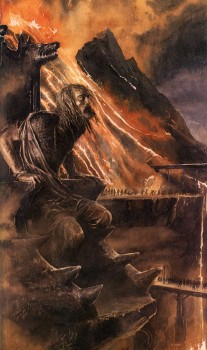

This is a powerful work. There are passages of great mythic proportions, particularly Morgoth’s confrontation with Húrin and the haunting description of the great mountain of the elven and human dead built by the Orcs after their victory in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears:

Now by the command of Morgoth the Orcs with great labour gathered all the bodies of their enemies, and all their harness and weapons, and piled them in a mound in the midst of the plain of Anfauglith, and it was like a great hill that could be seen from afar, and the Eldar named it Haudh-en-Nirnaeth. But grass came there and grew again long and green upon that hill alone in all the desert; and no servant of Morgoth thereafter trod upon the earth beneath which the swords of the Eldar and the Edain crumbled into rust. The realm of Fingon was no more, and the Sons of Fëanor wandered as leaves before the wind. To Hithlun none of the Men of Hador’s House returned, nor any tidings of the battle and the fate of their lords.

Simultaneously, it feels very real and grounded. The world of Men isn’t of glittering palaces and towers, but of wooden halls and palisades. It feels like Europe in the days of the Germanic Volkwanderung, when a migratory people moved into the great empty forests of Northern Europe. Their reduction to servitude under the Easterlings echoes the conquest of the Britons by the Saxons in the same broad time period. As I described earlier, the actions of the characters, heroes and villains alike, are psychologically believable and nuanced. One of Tolkien’s great achievements here is weaving the mythic into the realistic and it not feeling incongruous.

Simultaneously, it feels very real and grounded. The world of Men isn’t of glittering palaces and towers, but of wooden halls and palisades. It feels like Europe in the days of the Germanic Volkwanderung, when a migratory people moved into the great empty forests of Northern Europe. Their reduction to servitude under the Easterlings echoes the conquest of the Britons by the Saxons in the same broad time period. As I described earlier, the actions of the characters, heroes and villains alike, are psychologically believable and nuanced. One of Tolkien’s great achievements here is weaving the mythic into the realistic and it not feeling incongruous.

In addition to the self-destructive Túrin, the book introduces one of Tolkien’s most memorable characters: the dragon, Glaurung. Filled with the dark spirit of his master, the dragon is a manipulator of people, able to convince them that their darkest natures are their truest selves. He moves through the later sections of the book with a black, almost gleeful malevolence that is unmatched by any of Tolkien’s other villains.

The history of The Children of Húrin is complicated and I’ll only go into a few details here. Tolkien worked on the story for many years and never finished it to his satisfaction. Much of it is contained in The Silmarillion, but not all of it. Over the several decades before its publication, Christopher Tolkien compiled all the bits and pieces his father wrote and finally arranged them into a coherent single narrative tale. Despite it being nested within the greater work that comprises The Silmarillion, he managed to craft it into an enthralling standalone story. At the same time it expands on that book, bringing one of its main stories to greater life.

This is a significant work of fantasy and a meaningful addition to the catalogue of works by one of the primary founders of modern fantasy fiction. I’m a little embarrassed I’ve only just read it even though it’s been out for a decade. It’s also a beautiful book, filled with moody, eerie paintings and black and white drawings by Alan Lee.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now.

I love the Silmarillion. I just started my first reread of it last week.

I read the Children of Hurin not long after i read the Silmarillion for the first time. I thought it was a good companion and that the detail it added was worth reading.

I don’t know how much Christopher Tolkien had to edit, but it’s not just a collection of unfinished writings. The book has a solid narrative arc.

I received the newly released Beren and Luthien as a Christmas gift. Hopefully that works as well as Children of Hurin does.

Another well written review, Fletcher. I really enjoyed Children of Hurin, and am looking forward to Beren and Luthien, too. One thing I did notice after a recent screening of The Hobbit and LOTR is the cinematography. Once the characters leave the Shire, and as events unfold, the films’ visual atmosphere grow darker. I think this may have been an attempt to capture some of the despair and gloom in Tolkien’s work. I remember the first time I read The Hobbit, back in 1968, and was so surprised to see the novel grow darker and much less of a children’s book. LOTR is the same, too: once out of the Shire, the shadows start to fall. I sensed that gloom and despair while The Children of Hurin, and especially The Silmarillion. There was a dark side to JRR, and he used it beautifullyi n his stories.

FWIW, most of what was published in Children of Hurin had originally appeared in Unfinished Tales — I haven’t done a side-by-side comparison or anything, but I think CJRT mostly added some bridging text from the Silmarillion to the standalone book version (for sections that were incomplete in the original).

JRRT had a habit of going back and revisiting the same story multiple times in multiple lengths & levels of detail — the more high-level versions ended up in the Silmarillion, while the expanded (and generally incomplete) versions are in Unfinished Tales or the History of Middle-Earth volumes.

Great article about a great story.

@Glenn – Absolutely, it’s a finished, complete story, not just bits and pieces cobbled together. I haven’t read B & L yet either, but from things I’ve read, it is less a straight tale and more a detailed account of how the tale evolved and includes various edits and earlier versions. Of course I could have gotten that all wrong. I’m hoping to read it soon and find out for myself.

@Joe B – Thank for the link on FB. I’ll say it here, I have a visceral dislike for Peter Jackson’s films that I won’t rant about here. I agree that his darkened palette was an effort to mimic the darkened atmosphere of the books, but was only physical darkness and lacked any of the melancholy and loss present in the books.

@Joe H. – Thank you. To do this book justice I should’ve taken the time to reread the sections of Unfinished Tales and The Silmarillion that parallel Children. I found this book to read more naturalistically (is that actually a word?) than The Silmarillion and eschew the more mythic tone of much of that book for a more ‘realistic’ one. I’d like to see if that’s an accurate impression or merely the evidence of a faulty memory of the other texts.

@Fletcher — OK, I just got down my copies of the three books. The version in the Silmarillion is much shorter — maybe 30 pages, all told? The standalone version is mostly based on the text as it appeared in Unfinished Tales (and the few places I actually compared side-by-side matched word-for-word), but in the second appendix CJRT talks about the differences between the standalone version and the Unfinished Tales version, of which there are apparently more than I remembered.

You’re completely correct that this book is much more naturalistic or novelistic than the Silmarillion, which has the more mythic, maybe even King James-style prose.

As I think about it, I’m happy that they did publish the standalone version, if for no other reason than that it’s probably much more approachable to general readers than something like Unfinished Tales, which is a much more academic text.

And as I think about it, I’m also reminded that it’s been almost exactly five years since the last time I reread Tolkien, so I’m probably overdue.

I quite enjoyed this Boo, but it’s far from perfect.

One thing I’ve come to accept is I love Tolkien’s world building and ideas. But not his actual writing.

As such, I consider Peter Jackson’s films an overall improvement on the story.

I have my strengths (few as they may be) in my BG posts, but I wish I could write book reviews this well:

‘That is not the case here. The Children of Húrin is a darker book than much of what’s current, and the violence, written by a man who survived the Battle of the Somme, and perforce knew what real war and sudden death were like, feels more realistic and appropriate than in many other fantasy novels. Without succumbing to the modern penchant for explicit gore, this is a book streaked with blood and filled with violent death of the guilty, innocent, and indifferent alike.’

Well done.

@Joe H – Thanx for the legwork.

@MithradnirOlorin – Them’s fighting words to me, sir! 😉 I’m at present working on a post for my own site about the filmed versions of Tolkien and I’ll go into some detail about my issues with Jackson’s movies.

@Bob B. – Thank you very much. Sadly, I wing it a little too often on my reviews (read too fast, write too fast and at the last minute), but every now and then the material’s powerful enough make me rise above my sloth and limitations.