Fantasia 2017, Day 19: Heightened Realities (Night Is Short, Walk On Girl, Deliver Us, and Blade of the Immortal)

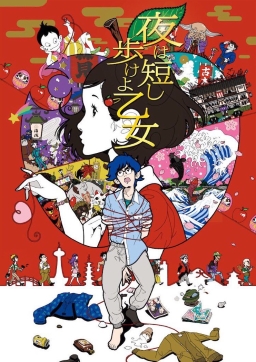

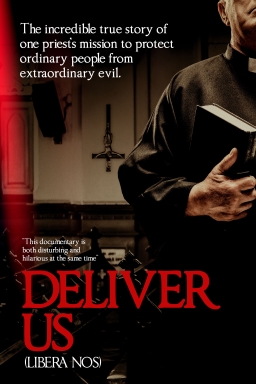

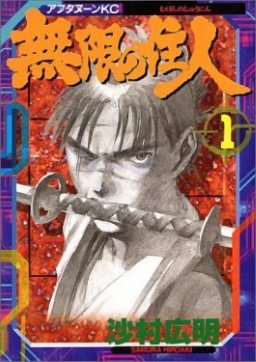

On Monday, July 31, I had three movies I wanted to see at the Fantasia Festival. First up was a surreal Japanese animated comedy, Night Is Short, Walk On Girl (Yoru wa Mijikashi Arukeyo Otome) in the De Sève Theatre. Then I’d stay at the De Sève to see an Italian documentary, Deliver Us (the English translation of the Latin title Libera Nos), about real-life exorcisms. The day would wrap up in the Hall Auditorium with a screening of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the best-selling supernatural samurai manga Blade of the Immortal (Mugen no Junin). It looked, all told, like a lovely day.

On Monday, July 31, I had three movies I wanted to see at the Fantasia Festival. First up was a surreal Japanese animated comedy, Night Is Short, Walk On Girl (Yoru wa Mijikashi Arukeyo Otome) in the De Sève Theatre. Then I’d stay at the De Sève to see an Italian documentary, Deliver Us (the English translation of the Latin title Libera Nos), about real-life exorcisms. The day would wrap up in the Hall Auditorium with a screening of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the best-selling supernatural samurai manga Blade of the Immortal (Mugen no Junin). It looked, all told, like a lovely day.

Night Is Short, Walk On Girl was written by Tomohiko Morimi from a novel by Makoto Ueda, and directed by Masaaki Yuasa. Yuasa’s previously overseen an animated TV adaptation of another Ueda novel, Tatami Galaxy; the stories share a setting and some minor characters, but there’s nothing obtrusive to someone like me who has neither seen nor read Tatami Galaxy. Walk On Girl takes place in Kyoto, following a group of university students through a long night of seeking love, of seeking a long-lost and beloved book, and of encountering supernatural and near-supernatural entities. It mainly centres on a male student, called only Senpai (‘senior,’ voiced by Gen Hoshino), who is in love with a girl called Kurokami no Otami (literally, ‘the girl with black hair,’ here played by Kana Hanazawa). Senpai’s been arranging seemingly-accidental meetings, hoping Otami will notice him; on the night the film follows them, she goes partying and ends up looking for a copy of a beloved storybook from her childhood. This swiftly leads into a proliferation of subplots and genuinely zany characters — from the God of the Old Books Market (Hiroyuki Yoshino), to the School Festival Executive Head (Hiroshi Kamiya) who keeps the University campus under constant surveillance, to ‘Don Underwear’ (Ryuji Akiyama) who will not change his drawers until he finds (through the medium of pop-up theatrical happenings) the girl he once saw and fell in love with. The film whirls along through the night in a delirious whirl of pub crawling, dancing, philosophers (dancing and otherwise), guerilla theater, used book fairs, surveillance, cross-dressing, wishes, bad colds, punching technique, clocks, night, and true love.

I was worried for most of the film that Senpai’s obsession with Otami, which at least borders on stalking, would be glossed over. In fact it is at least addressed toward the end of the film, and the constant humiliations Senpai brings on himself throughout the movie certainly can be seen as a kind of poetic justice for his actions. In this as in much else the film is aware of its dark undertones, but maintains a generosity of spirit despite them. It’s a movie that maybe more than any other I’ve seen captures the university experience — or what one might hope the university experience would be like. It does this without naivete; it is clearly the product of older creators telling a tale of youth, but doing it without either speaking down to the young in any way or, conversely, romanticising the experience of youth.

Paradoxically, while the narrative has the experience of age behind it in its structure and themes (particularly toward the end), it also has youth in its bones. This is an energetic film, frantically paced, throwing in idea after idea, character after character. There’s a feel like a classical farce in the rapidity of events, the crossing-over of unexpected people, and the mounting sense of confusion. And yet there’s more to it than that, as after building to a major set-piece it becomes hallucinatory and I suppose philosophical, a meditation on time and love. It’s supremely effective, and remarkably powerful.

Paradoxically, while the narrative has the experience of age behind it in its structure and themes (particularly toward the end), it also has youth in its bones. This is an energetic film, frantically paced, throwing in idea after idea, character after character. There’s a feel like a classical farce in the rapidity of events, the crossing-over of unexpected people, and the mounting sense of confusion. And yet there’s more to it than that, as after building to a major set-piece it becomes hallucinatory and I suppose philosophical, a meditation on time and love. It’s supremely effective, and remarkably powerful.

Visually, the designs are stylised but detailed, cartoonish in the best sense. Colours are bright, flat, and attractive, building a remarkable world. An extended hallucination near the end of the film, which seems to owe a little to Yellow Submarine (of all things) is a brilliant set-piece, but the imagery throughout is a splendid mixture of simplified design and precise storytelling. Characters are brought to life in the angle of a smile, in the way they run or fall.

There’s also a mixture of the surreal and the supernatural that makes this story perfect for animation. It’s a film that frequently leaves everyday reality far behind; perhaps more accurate to say that it’s a story that begins with everyday reality but soon leaves it far behind only to later cross paths with it from time to time. So the night lasts peculiarly long; there are supernatural creatures; odd things happen with time. It all feels of a piece. This is definitely the story of modern-day university students, and if it involves a tengu, then fine, there’s a tengu.

What gives the film an extra texture are the adults around the students. They reflect on their own university days, and while there’s some nostalgia to that, there’s something more beside. Some are able to join in on the young folks’ adventures, at least for a time. But then time is what this is all about. There’s a fatalistic sense to the film that is in no way sad or depressing. It’s an uplifting story about the brevity of youth and the inevitable passage of time, which is in its own way quite an accomplishment.

What gives the film an extra texture are the adults around the students. They reflect on their own university days, and while there’s some nostalgia to that, there’s something more beside. Some are able to join in on the young folks’ adventures, at least for a time. But then time is what this is all about. There’s a fatalistic sense to the film that is in no way sad or depressing. It’s an uplifting story about the brevity of youth and the inevitable passage of time, which is in its own way quite an accomplishment.

More than that, for all the stretching of the borders of reality, it feels recognisable. I used to do some teaching at the college level, and the characters in this movie felt like convincing depictions of college students in a way I rarely see. I think more than anything it’s the sense that the youths here both party and learn; they’re drinkers, but also readers. Otami’s looking for a book from her childhood, but also knows that “books connect everything.” It strikes me as unusual to see both aspects of university life given similar weight in the same story, but there’s something of that here.

And I think this is important because it speaks to why the movie works: the strength of its characters. More precisely, the movie works because it’s damned funny, and it’s funny because the jokes grow out of credible and relateable characters. Cartoony characters, yes. Characters running around and falling from great heights and getting into improbable mix-ups, yes, all these things. But characters we swiftly come to know, characters that are familiar, that are believable. The further the movie goes on, the deeper and more wondrous it becomes, and the more weight the characters come to carry. And yet it’s always charming. It’s a remarkable, fast, witty movie about love and time and growing old; and it’s a thorough success.

And I think this is important because it speaks to why the movie works: the strength of its characters. More precisely, the movie works because it’s damned funny, and it’s funny because the jokes grow out of credible and relateable characters. Cartoony characters, yes. Characters running around and falling from great heights and getting into improbable mix-ups, yes, all these things. But characters we swiftly come to know, characters that are familiar, that are believable. The further the movie goes on, the deeper and more wondrous it becomes, and the more weight the characters come to carry. And yet it’s always charming. It’s a remarkable, fast, witty movie about love and time and growing old; and it’s a thorough success.

After the film, there was a question-and-answer period with director Masaaki Yuasa, who began by saying that he hoped we’d all followed the fast-paced film. The first question asked what had inspired that pace, to which he said that he pays close attention to timing, and for this film the many goofy scenes meant it had to be fast. The original novel was funny, he said, and he wanted the same rhythm for the film. Asked how he came up with the unusual visual style of the film, he said he wasn’t trying to create a specific style so much as trying to portray the book faithfully.

Asked why the characters had no name, Yuasa said again the characters weren’t named in the book; the author wanted readers to imagine them. He noted that this became difficult at points in the film where they had to show a name written down, and so had to obscure the name with a lighting trick. A questioner observed that time was critical in the movie, which made a night last forever the way youth sometimes felt in later age; Yuasa said that the book had four stories, which he combined into one for the film, but which following the title all had to take place in a single night. He wanted to bring over an idea from another book, about the joy of giving useless time to someone and he wanted to show how time goes faster as you age.

Asked why the characters had no name, Yuasa said again the characters weren’t named in the book; the author wanted readers to imagine them. He noted that this became difficult at points in the film where they had to show a name written down, and so had to obscure the name with a lighting trick. A questioner observed that time was critical in the movie, which made a night last forever the way youth sometimes felt in later age; Yuasa said that the book had four stories, which he combined into one for the film, but which following the title all had to take place in a single night. He wanted to bring over an idea from another book, about the joy of giving useless time to someone and he wanted to show how time goes faster as you age.

Asked how long it took to make the film, Yuasa said he’d wanted to make it after his previous Kyoto-set work Tatami Galaxy, but it didn’t then happen. He returned to it after completing another film, Lu Over the Wall (which also played Fantasia this year; review to come), and didn’t want to miss the chance to complete it. He used the team from Lu to make this movie. Finally, asked why he set the film in Kyoto, he said the original novel was set there; the city, he said, has a very mystic mood, with lots of students, so that one feels both a lot of freedom and a lot of history. You feel, he said, that you can find there the sort of people you can see in the film.

That ended the questions. Next came a definite change in tone, with a film that was very nearly a polar opposite to Walk On Girl.

That ended the questions. Next came a definite change in tone, with a film that was very nearly a polar opposite to Walk On Girl.

Deliver Us is a documentary directed by Federica di Giacomo about the rite of exorcism. We watch priests perform the rite as men and women snarl and contort themselves, apparently under the influence of one or more demons. And we follow the people who have undergone exorcism, people who keep suffering from possession and coming back. We learn about their lives, as we learn about the priests’ attitude to the rite, as we see them speak with the suffering people who have come to them for relief.

This is observational cinema; we have no voice-overs, no information provided for us. There seem to be few interviews. We mostly see the interaction of priests and possessed, and the interaction of the possessed with the other people in their lives. We in the audience can conclude what we like about what we see; are the ostensibly possessed suffering from demons, from insanity, or from excess theatricality and a need for attention?

For what it’s worth, as an agnostic tending to atheism I found myself naturally viewing the film as an example of mentally and emotionally troubled people seeking guidance from a kind of therapist. Of course, it’s quite correct to say that therapists are a modern form of priests like these — of religious authority figures who can intercede with the numinous world, the world of dreams and fears. If the therapist is a contemporary version of the magus who can control the spirit-world for the good of the community, that also is what an exorcist is. And yet surely one of the most charming aspects of the film is the resolute everydayness of the exorcists. These are mundane aging priests who try to talk sense into the people they deal with, and occasionally have to lay on hands and cast out demons (or sometimes do so over the phone). It’s all one; they do what they have to do.

It does mean that, at least to me, there isn’t really any horrific atmosphere or conversely any sense of awe; no sense of another world impinging on this one. There are disturbing outbursts, people growling and shrieking and throwing things, but there’s a sense that this too is part of life. In a way this means the filmmakers can approach touchy issues (whether of religion or of mental health) without taking any kind of stance. But then the reality is that the editing of the film is a series of choices. We’re shown what the filmmakers want us to see, and ultimately I think that the lack of a sense of horror is deliberate. I think the relative lack of ceremony shown in the film is deliberate. I think we’re meant to be skeptical, and I think the priests themselves are often skeptical.

This is fine, but then what’s the point of the film? The film’s a slow build, but what does it build to? There’s a conversation near the end between one of the frequently-possessed women and a friend that seems at first remarkably open, until you realise that they know they’re being filmed. I think that’s got to do with the point of the film, the way people perform their own horrors. I think it’s about people driving themselves into a certain kind of state, and relying on the priests to get them through. But to what end?

This is fine, but then what’s the point of the film? The film’s a slow build, but what does it build to? There’s a conversation near the end between one of the frequently-possessed women and a friend that seems at first remarkably open, until you realise that they know they’re being filmed. I think that’s got to do with the point of the film, the way people perform their own horrors. I think it’s about people driving themselves into a certain kind of state, and relying on the priests to get them through. But to what end?

I wish there had been more context given. At the end of the movie we learn that there’s an increasing demand for exorcisms; we see an international institute established to train exorcists. The implication is that what we’ve seen being enacted in a few places in Italy is becoming more common, that more and more people suffer from the extreme mental states we’ve seen. Why, though? What’s happening here, really?

We get glimpses into the everyday lives of the possessed (who are not possessed around the clock, but are regularly visited by demons the priests cast out at special masses or in one-on-one sessions). We see them with their families or lovers. But how much do we see? How much can we see? What are we not seeing, that we cannot know about them? In a sense, the documentary forces us to think about the limits of the form. If there is an invisible world of spirits, after all, how will it appear in the visual medium of film?

As a visual work, Deliver Us has an intense grounded feel. There’s a distinct neorealist atmosphere; the film lives in a series of cramped interiors. In old buildings with peeling paint, in comfortable old wood furniture, in apartments and churches — but not in cathedrals. Again, there’s nothing particularly grand here. There’s no sense of weighty ritual, of the machinery of bell, book, and candle. Priests tend to the possessed in back rooms, or discuss in small offices what is to be done. It’s as though possession comes to be a part of life.

As a visual work, Deliver Us has an intense grounded feel. There’s a distinct neorealist atmosphere; the film lives in a series of cramped interiors. In old buildings with peeling paint, in comfortable old wood furniture, in apartments and churches — but not in cathedrals. Again, there’s nothing particularly grand here. There’s no sense of weighty ritual, of the machinery of bell, book, and candle. Priests tend to the possessed in back rooms, or discuss in small offices what is to be done. It’s as though possession comes to be a part of life.

And yet precisely because of that realist approach it’s hard to avoid feeling that what goes in this movie is profoundly weird. The possessed here are certainly going through some extreme state of consciousness, but we see that overwhelmingly in mundane surroundings. The juxtaposition of the two things has a tendency to reduce the violence of the experience to the mundanity around it. But then it also hints that the quotidian is as violent, as extreme, as the shrieking people we see anchored here in the world; it hints that the world is bigger than we understand, can comfortably stretch to include profound spiritual experiences. But from the outside, what can we really know about these things?

Deliver Us is an interesting experience, but I find more interesting as a concept than as a film. At 94 minutes, it feels long. That may be because I did not, at one viewing, grasp the movie’s approach to structure. But while it plays with some fascinating ideas, and puts some powerful images on screen of real people in the grip of extreme experiences, I didn’t find that it built anything coherent around or out of those images. Still, it’s an interesting example of cinematic form, and absolutely necessary watching for anyone with an interest in the topic of contemporary exorcism or, for that matter, the topic of contemporary Italian religious culture.

Deliver Us is an interesting experience, but I find more interesting as a concept than as a film. At 94 minutes, it feels long. That may be because I did not, at one viewing, grasp the movie’s approach to structure. But while it plays with some fascinating ideas, and puts some powerful images on screen of real people in the grip of extreme experiences, I didn’t find that it built anything coherent around or out of those images. Still, it’s an interesting example of cinematic form, and absolutely necessary watching for anyone with an interest in the topic of contemporary exorcism or, for that matter, the topic of contemporary Italian religious culture.

My final film of the day was in the big Hall Auditorium, an epic adaptation of Hiroaki Samura’s Blade of the Immortal. The movie was written by Tetsuya Oishi and directed by Fantasia favourite Takashi Miike, his second high-profile manga adaptation of this year’s festival after Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. Set in feudal Japan, the manga was known for its extreme violence, which seemed a good fit with Miike’s sensibilities. How would it work out?

The movie introduces us to the supremely skilled samurai Manji (Takuya Kimura), who is saved from a tragic death by a witch-woman (Yoko Yamamoto) who implants supernatural bloodworms into his body. The worms give him immortality and the ability to heal from any wound. Fifty years later, having retreated from the world, Manji is visited by a young girl named Rin (Hana Sugisaki), who seeks vengeance on the Itto-ryu, evildoers who killed her parents. He turns down her request for help, but then must save her life from the Itto-ryu. This starts a chain of events in motion that draws Manji ever deeper into a struggle against the various warriors of the Itto-ryu and their chief, Kagehisa (Sota Fukushi).

The movie’s a very compressed adaptation of (a large chunk of) the 30-volume manga. I’ve not read the manga, but from speaking with people who have I gather that the adaptation reduces several major characters to supporting parts, even cameos. That said, for the most part the compression of the story into two-and-a-half hours of film is done smoothly. (I will note here that Manji’s costume design is altered from the manga, where he wears a prominent insignia of an ideogram that looks like a reversed swastika; the film replaces it with a different character.) There is some repetition to the plot, as Manji fights one Itto-ryu warrior after another, but the various warriors have highly individual visual designs and fighting styles, which goes some way to ward off any sense of sameness.

The movie’s a very compressed adaptation of (a large chunk of) the 30-volume manga. I’ve not read the manga, but from speaking with people who have I gather that the adaptation reduces several major characters to supporting parts, even cameos. That said, for the most part the compression of the story into two-and-a-half hours of film is done smoothly. (I will note here that Manji’s costume design is altered from the manga, where he wears a prominent insignia of an ideogram that looks like a reversed swastika; the film replaces it with a different character.) There is some repetition to the plot, as Manji fights one Itto-ryu warrior after another, but the various warriors have highly individual visual designs and fighting styles, which goes some way to ward off any sense of sameness.

On the other hand, it does create an oddly familiar comic-book sense. After a while, you begin to recognise Itto-ryu warriors by the way they dress — against a backdrop of peasants, the flamboyant bright colours of the warriors really stand out. In fact, they look like supervillains. At which point one notes that Manji’s a long-lived warrior with a healing factor who hangs around with a young girl. I have no idea whether the character of Wolverine had any influence on the manga, but it’s an interesting coincidence that the film comes out the same year as Logan, which has a vaguely similar story.

At any rate, this is a colourful, well-choreographed action movie. There is a lot of violence, but not as much gore as one might have expected from Miike given this material. It’s probably also fair to say there’s not as much of an individual sensibility here as one might have hoped. It’s inventive and nicely crafted, but for better or worse there’s nothing especially startling here. This is a samurai movie with supernatural and super-hero touches that tells its tale at length, rises through a series of duels to a major set-piece battle, and concludes with a satisfying amount of brutality.

Is it about anything in particular? The basic conflict between Rin’s parents and the Itto-ryu boils down to a philosophical difference over the proper approach to swordplay (the Itto-ryu believe in winning at all costs), but this is relatively underplayed in the film. Still, one might argue that it flavours much of what we see: Manji, a man slightly out of time, stands for an old-fashioned ideal. At the same time, the movie goes some distance to demonstrating why Manji removed himself from the world — ideals tend to become subordinated to violence. And so it is here, as we’re watching the movie for the sake of the action. Form follows theme, I suppose.

At any rate, the movie’s inventive in coming up with new ways to threaten Manji. Of course Rin ends up in danger quite a lot, but Manji himself has to face enemies who’ve worked out some effective ways of threatening him. Much as he himself has to put himself through some terrible tortures for the sake of winning his fights. It’s nicely varied without feeling as though it connects to anything deeper.

At any rate, the movie’s inventive in coming up with new ways to threaten Manji. Of course Rin ends up in danger quite a lot, but Manji himself has to face enemies who’ve worked out some effective ways of threatening him. Much as he himself has to put himself through some terrible tortures for the sake of winning his fights. It’s nicely varied without feeling as though it connects to anything deeper.

There is, oddly, a kind of generosity to the film. It’s aiming at one thing, but it gives us a lot of that thing. A lot of different characters, a lot of different fights, a lot of different weapons. It’s ruthless about killing off its villains, too, which at least creates a real sense that Manji’s getting somewhere: he leaves quite a trail of bodies behind him. It may be most distinctly a Miike film in this way: it holds nothing back creatively, and isn’t afraid to introduce characters just to kill them.

Ultimately, this is a movie that succeeds in what it sets out to do. It’s long, but doesn’t feel it. Dedicated fans of the manga may not care for the choices made in the adaptation. But as a film, it works quite well. If you want samurai action with a goodly amount of blood and a larger-than-life tone, this is the movie you want to see.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.