Fantasia 2017, Day 16: Control and Resistance (Fritz Lang and The Crazies)

On Friday, July 28, I had two films on my schedule at the Fantasia Festival. The first was a German period crime film with biographical aspects, a movie called Fritz Lang that imagined the great director of the title mixed up with the killings that would shape his now-classic film M. The second was a screening of George Romero’s 1973 film The Crazies, arranged quickly by the festival’s organizers as a tribute following Romero’s death only 12 days before. Together the movies would make for a day that, to me, exemplified much of what is best in Fantasia: a profound appreciation of film history of every kind, mixed with challenging genre artistry.

On Friday, July 28, I had two films on my schedule at the Fantasia Festival. The first was a German period crime film with biographical aspects, a movie called Fritz Lang that imagined the great director of the title mixed up with the killings that would shape his now-classic film M. The second was a screening of George Romero’s 1973 film The Crazies, arranged quickly by the festival’s organizers as a tribute following Romero’s death only 12 days before. Together the movies would make for a day that, to me, exemplified much of what is best in Fantasia: a profound appreciation of film history of every kind, mixed with challenging genre artistry.

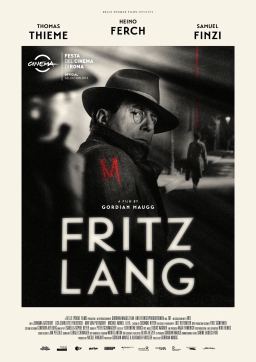

Fritz Lang was directed by Gordian Maugg from a script he worked on with Alexander Häusser. Opening in 1929, the black-and-white film follows director Fritz Lang (Heino Ferch) in the wake of the relative failure of a string of Lang’s films, including his pioneering science-fiction movies Metropolis and Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon). Casting about for a new idea for a film that will satisfy him artistically and also make money, Lang hears about a series of murders in the city of Düsseldorf. He grows fascinated by the killings, and travels to Düsseldorf to take a hand in the investigation. But why is he so drawn to the lurid crimes?

There’s a kernel of reality in Fritz Lang. Lang did research the Düsseldorf killings, and they did partially inspire his next film, M (though at times Lang would downplay the link, pointing to other murders he researched). The movie at hand greatly expands Lang’s involvement with the murders, and invents any number of scenes in which he interacts with the police and killer. That’s fair enough for a historical drama, but at the same time the film’s primarily interested in what makes Lang tick — why he’s drawn to make a story of the killings, and how those killings parallel events in his life. In order to make those parallels dramatically forceful, the movie then has to dramatise certain events in Lang’s life which in reality are to an extent mysterious. Again there’s nothing wrong with that. But it does make for an odd and at times uneasy blend of period mystery and biopic.

Are we watching this movie to see a mystery story starring a big name from the past, a more ambitious version of a novel in which Jane Austen investigates a murder? Or are we watching the movie to see an individual’s personality dissected, with special attention to their relationship to violence? If the latter, why use Fritz Lang? Does the parallel with M bring out any notable theme? Or is the movie a formal exercise, using the investigation as a way to link cinema and reality?

Are we watching this movie to see a mystery story starring a big name from the past, a more ambitious version of a novel in which Jane Austen investigates a murder? Or are we watching the movie to see an individual’s personality dissected, with special attention to their relationship to violence? If the latter, why use Fritz Lang? Does the parallel with M bring out any notable theme? Or is the movie a formal exercise, using the investigation as a way to link cinema and reality?

My impression is that Fritz Lang tries for all these things at different times, and occasionally falls between stools. I would say that it is predominantly not a mystery so much as it is a drama; the conclusion is a conversation in which no crime in the film’s present day remains to be solved, only individual passion gratified. A parallel track of flashbacks to earlier in Lang’s life (in which the young Lang’s played by Max von Pufendorf) has in some ways a more powerful payoff, increasing the sense that the story’s more about what made Lang the man he is — the artist who will create M.

There’s minimal suspense to the film, which opens with the murderer (Samuel Finzi) in custody describing his killings. (He tells us how afterward “well, then, I went to the cinema!” as though to emphasise the mixture of violence and film.) Almost inevitably, then, the movie becomes an investigation into the character of Lang. There’s no hero-worship in its depiction of the director; if anything, there’s something of the opposite, as the movie pushes its drama by presenting a deeply flawed man. We end up with a Lang who is a kind of shadow to the killer he’s investigating, someone as much on the outside of normal society, someone with as vexed a relationship to conventional morality.

In a film conscious of the historical moment in which it takes place, we have many intimations of the growing strength of the Nazi party; one of the best comes in a moment when Lang briefly adopts the pose of a SS major to trick some Nazis into yielding him the table he wants at a public restaurant. It brings home the way Germany was going, but also shows Lang slipping into the role of villain, masquerading as one of the fascists — as well as presenting him as a confident director, staging events for his own benefit. It’s one of the most disquieting moments in the film, and oddly effective.

In a film conscious of the historical moment in which it takes place, we have many intimations of the growing strength of the Nazi party; one of the best comes in a moment when Lang briefly adopts the pose of a SS major to trick some Nazis into yielding him the table he wants at a public restaurant. It brings home the way Germany was going, but also shows Lang slipping into the role of villain, masquerading as one of the fascists — as well as presenting him as a confident director, staging events for his own benefit. It’s one of the most disquieting moments in the film, and oddly effective.

The problem, I feel, is that not much is done in the movie with the idea of a commonality between Lang and the killer, between director and character. Does confronting a murderer change Lang’s idea of how to present him? Is there anything in him that exceeds Lang’s grasp? Or conversely is he lesser than Lang might have expected? That’s not clear. By the end of the film we know why Lang is drawn to the killer, but not why that matters.

It has to be said that Fritz Lang is technically well-made. The 1920s are reconstructed nicely for the film, and when (inevitably) the character of Lang is inserted into clips of M, the moments are chosen well both dramatically and thematically, insisting on the tightness of fiction and fact — though one can argue that tightness is undermined by the extreme fictionalising that goes on in the presentation of fact. In any event, I will say that while Lang’s work was notable for its noirish atmosphere, the black-and-white images here feel by and large mundane with only a few exceptions. A scene where Lang follows a woman at night is powerfully dramatic, but otherwise the movie seems to insist on the mudanity of events.

Which, to be fair, might be its point. Lang’s vision is not, perhaps, the vision of the world as it is (and indeed there’s a certain amount made in the movie about Lang’s eye injury from World War One). Lang here is a man who tries to control the world around him, and thus the men and especially the women around him; and if his analogue in this film is a murderer, then also Germany would soon produce a vile crew of would-be visionaries who saw themselves in the villain of Lang’s film (the Nazis would ban the movie in 1934). Fritz Lang the film speaks, then, to that drive to control and that fascination with violence. Its main flaw may be that it suffers by comparison to its source: it’s not a patch on Lang’s own work. But then, not being as great as some of the greatest works of cinematic art in the history of the form isn’t the worst thing in the world.

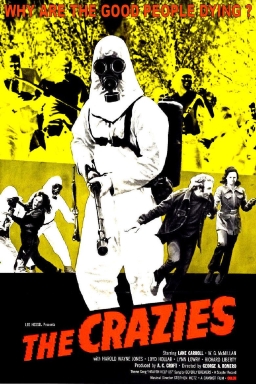

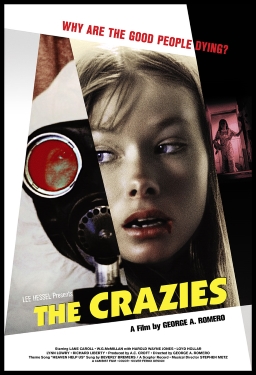

I saw Fritz Lang at the De Sève cinema, which was the same venue chosen for the commemorative screening of George Romero’s The Crazies. The screening was hosted by Fantasia’s Mitch Davis, who described the film as like “the forgotten Beatle to me.” He described it as Romero’s angriest film, about social and political confrontation, about his anger at and distrust of the American military; and he spoke of how it was an example of Romero’s editing, how it showed him cutting for movement and not for rhythm. The film we were about to see came from a new 4K restoration put together by Arrow Films, presented at Fantasia for the first time anywhere.

I saw Fritz Lang at the De Sève cinema, which was the same venue chosen for the commemorative screening of George Romero’s The Crazies. The screening was hosted by Fantasia’s Mitch Davis, who described the film as like “the forgotten Beatle to me.” He described it as Romero’s angriest film, about social and political confrontation, about his anger at and distrust of the American military; and he spoke of how it was an example of Romero’s editing, how it showed him cutting for movement and not for rhythm. The film we were about to see came from a new 4K restoration put together by Arrow Films, presented at Fantasia for the first time anywhere.

The Crazies, directed by Romero from a screenplay he wrote based on a script by Paul McCollough, is the story of a small town in Pennsylvania which becomes infected by a bioengineered virus created by the American military. The virus causes violent insanity in its victims, followed sooner or later by death. An accident before the start of the film sets events in motion, and we watch the initial confusion as the virus takes hold and the military moves in to try to contain it. Then the film splits roughly into two strands. In the first, Colonel Peckem (Lloyd Hollar) tries to deal with the infected townspeople while a scientist named Dr. Watts (Richard France) struggles to find a cure. In the second, a small group of villagers led by firefighters and Vietnam veterans David (Will McMillan) and Clank (Harold Wayne Jones) try to escape the martial law Peckem establishes, and slip past his perimeter to freedom. But it soon becomes clear they’re not uninfected themselves.

There’s an unnervingly realistic feel to the film. The edits Davis mentioned help create a kind of documentary feel, especially when the camera shows us things unrelated to the dialogue — when Peckem gets the call to go to the infected town of Evans City, for example, we don’t see him on the phone much as he speaks but see him throwing things in his suitcase. The lighting is harsh, high-contrast, and for me felt oddly like a TV news report from the era. The acting’s intensely variable, at best, but the writing’s good at creating the sense of a small town and quickly sketching a network of relationships and histories among the characters.

The echoes of Vietnam are inescapable. Not only in David and Clank’s background. But in some of the incidental references: when a priest becomes infected, he protests the treatment of his flock by dousing himself with gasoline and setting himself on fire. The war, of course, was still going on at the time the film was made and here it remains an unspoken fact that gives a texture to events. What was the virus created for, if not to be used in war?

There’s something almost bracing, in fact, at Romero’s anger at the American military. In recent decades the military’s gained an increasing influence on American filmmaking (if you want to borrow military hardware as props for your film, for example, the military will vet your script) such that once-common critical depictions of the American armed forces have almost disappeared. Even relatively mild-mannered films like Wargames are rare if not nonexistent; a full-throated satire like this one, in which well-intentioned officers are in charge of overseeing a disaster caused by the structure they serve, is almost unimaginable. We’re told of the army here that “they can turn a campus protest into a shooting war,” and that disgust with the American war machine drives the film.

There’s something almost bracing, in fact, at Romero’s anger at the American military. In recent decades the military’s gained an increasing influence on American filmmaking (if you want to borrow military hardware as props for your film, for example, the military will vet your script) such that once-common critical depictions of the American armed forces have almost disappeared. Even relatively mild-mannered films like Wargames are rare if not nonexistent; a full-throated satire like this one, in which well-intentioned officers are in charge of overseeing a disaster caused by the structure they serve, is almost unimaginable. We’re told of the army here that “they can turn a campus protest into a shooting war,” and that disgust with the American war machine drives the film.

I found it impossible not to think of Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970) while watching. Both use similar cinematic techniques, with the confusion and quick pace of events in Romero’s infected city matching Altman’s overlapping dialogue, and of course both take aim at the American military. I think Romero’s film is superior, not least because Altman’s film strikes me as confused — it’s difficult to take a moralistic satire seriously when its leads are nearly as morally repugnant as the structure they’re ostensibly struggling against. In fact, Altman’s doctors don’t have any particular sense of character or principle; they’re nominally against the military, but only insofar as the military inconveniences them personally. Romero’s villagers have a greater distrust of the military, and if they’re mainly driven to action by the military’s action against them, at least they are actually driven to action — you know what they’re trying to do, and why. Altman’s vignettes stop more than conclude, while Romero’s film has an uncompromising and mostly tragic resolution.

And it does work as tragic, not just horrific. There aren’t a lot of large-scale set-pieces here, likely in part due to budget limitations, but that means that the film concentrates on building suspense and tension. In that, it’s quite effective. Since that means it’s spending a lot time getting us to invest in the characters, we’re engaged when bad things happen. Which is simple to say, but without effective writing it wouldn’t work. Romero’s clever enough and creative enough to come up with both strong character beats and strong incidents demonstrating the effects of the virus, and often both at once.

It’s not a perfect film. One might argue that the women, notably David’s girlfriend Judy (Lane Carroll), don’t get very much to do. And the acting does make it difficult to watch at times. But the story’s solid and well-structured. And Romero’s direction is crisp and powerful, catching the mood of chaos and growing insanity perfectly. The sense of slow degeneration in the film is nerve-wracking. We watch people who don’t know what’s happened, and who may already be too late to stop it, as bit by bit options are whittled away.

It’s not a perfect film. One might argue that the women, notably David’s girlfriend Judy (Lane Carroll), don’t get very much to do. And the acting does make it difficult to watch at times. But the story’s solid and well-structured. And Romero’s direction is crisp and powerful, catching the mood of chaos and growing insanity perfectly. The sense of slow degeneration in the film is nerve-wracking. We watch people who don’t know what’s happened, and who may already be too late to stop it, as bit by bit options are whittled away.

If The Crazies is ultimately a horror film, it is in this sense. There’s a lack of certain rules to the movie beyond what the characters make up for themselves. Peckem struggles to impose an order on a town going increasingly mad, with dubious results. On the other hand, David and his friends try to escape madness, hatching plans as they need to in order to overcome obstacles; but in watching one knows that the faith they put in the rules they imagine are ultimately misplaced. If only we do this, they say, we will be safe. Sometimes they’re right. But not always. In establishing a world without rules beyond the ones we imagine, Romero creates something bleak and angry. And well worth seeing.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I’ve never seen the Romero original but I liked the 2010 remake of The Crazies starring Timothy Olyphant. It was really only a popcorn movie, but pretty good.

That’s good to hear! I knew it existed, but not much beyond that.