Fantasia 2017, Day 14, Part 2: Folklore and Fans (November and Tokyo Idols)

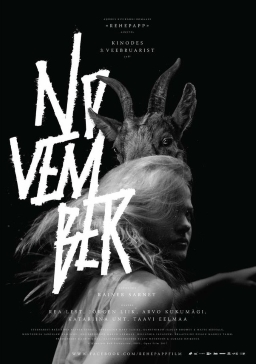

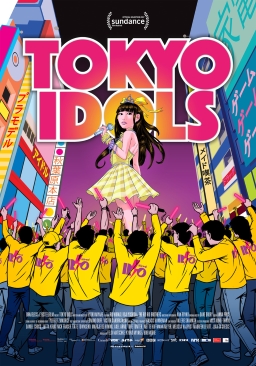

I wrote the other day about 78/52, the first movie I saw at Fantasia on Wednesday, July 26. It played at the De Sève Theatre, the smaller of the two main Fantasia cinemas, and as it happened I’d see two more movies there the same day. The first was an Estonian movie (technically an Estonian-Dutch-Polish co-production) called November, a period piece set among Northern forests, rich in folklore and cinematic beauty. The second was a documentary called Tokyo Idols, about the Tokyo-centred industry of young female pop singers.

I wrote the other day about 78/52, the first movie I saw at Fantasia on Wednesday, July 26. It played at the De Sève Theatre, the smaller of the two main Fantasia cinemas, and as it happened I’d see two more movies there the same day. The first was an Estonian movie (technically an Estonian-Dutch-Polish co-production) called November, a period piece set among Northern forests, rich in folklore and cinematic beauty. The second was a documentary called Tokyo Idols, about the Tokyo-centred industry of young female pop singers.

November was written and directed by Rainer Sarnet from the novel Rehepapp by Andrus Kivirähk. Shot in a sumptuous black and white, it shows us an Estonian peasant village in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, isolated among the deep woods, ruled by a family of Germans. We see the grinding poverty of pre-industrial village life and we see the German lords in their rich but decaying manor house. More significantly, perhaps, we see the world of spiritual forces and witchcraft within which the peasants live. Dead souls return to share a feast. Witches can teach a girl to take the shape of a wolf. Hidden treasures lurk under floorboards. Plagues take human form. And you can sell your soul to the devil to get a servant made of scraps of wood and other leftovers, a thing called a kratt; if you’re really cunning, if you know the trick of it, maybe you can cheat the devil and get away with your soul intact.

Against this rich background we see a love triangle develop. Liina (Rea Lest) is love with Hans (Jörgen Liik) who himself has his heart set on the German baroness. In and around this are other subplots and anecdotes of village life. A man becomes obsessed with the maid of the manor house. Older people see what might have in their own lives as Liina pursues Hans. Hans, meanwhile, also aspires to be a poet. But if he sells his soul for love, can he ever become the writer he wants to be?

This question strikes me as important because I think the film’s in an interesting tension with romanticism. It’s set at about the time of the flowering of romanticism in English and German literature, a time when folklore and peasant life were both beginning to become major subjects of literature. Also a time of emergent nationalism. A time when poets tended to shun the earthy for the sublime and even the gothic.

This question strikes me as important because I think the film’s in an interesting tension with romanticism. It’s set at about the time of the flowering of romanticism in English and German literature, a time when folklore and peasant life were both beginning to become major subjects of literature. Also a time of emergent nationalism. A time when poets tended to shun the earthy for the sublime and even the gothic.

November doesn’t make that mistake. It’s a profoundly earthy film, showing us peasant life in uncompromising and even beautiful naturalistic photography. It’s just that peasant life includes ghosts and magic, and accordingly the film includes these things, which are just as real as the trees in the forest and the ice on a winter lake. Here, the Germans in their out-of-place manor house are unreal; here, stories of Venice become fairy tales of a fantasy kingdom. The contrast between the Germans in their decaying home and the Estonians they nominally rule is particularly pointed — the distance between the manor house and the peasant village is more than spatial. I have no idea how this plays in Europe, but to me as a North American, it avoids an overly nationalistic sense if only because the Germans and Estonians seem hardly to connect with each other at all.

I can imagine a nationalistic reading of the film, but I note that the few reviews I’ve been able to find of the original novel says the book intentionally subverts that approach. It also suggests that Kivirähk’s novel is fundamentally satiric, which I would not say of the movie. There are definitely moments of earthy humour, and it may well be satirising aspects of Estonian culture of which I am woefully ignorant. But the presentation of myth and magic in November don’t, on the whole, feel like satire. There’s too much death and sublimity to be purely absurd — however much the absurd is strongly present. The idea of the soul is too powerful in this movie, too much of a thematic concern, to be solely ironic even if irony is there in the way things work themselves out.

The movie’s long, complex, and rich. Folktales are worked into the structure of the story, but there’s a humanistic focus that keeps the movie from collapsing into a fable-like flatness. The depth of the characters, the sense of history and everydayness to them, means that the folktale aspects don’t seem to control the story. That’s misleading, in a way — the shapes in the plot are what you might expect in a folktale. But the characters don’t relate to the fantastic aspects of their life the way that characters in a tale would. There’s a realness to them that can’t be captured in the strict outlines of a fable.

The movie’s long, complex, and rich. Folktales are worked into the structure of the story, but there’s a humanistic focus that keeps the movie from collapsing into a fable-like flatness. The depth of the characters, the sense of history and everydayness to them, means that the folktale aspects don’t seem to control the story. That’s misleading, in a way — the shapes in the plot are what you might expect in a folktale. But the characters don’t relate to the fantastic aspects of their life the way that characters in a tale would. There’s a realness to them that can’t be captured in the strict outlines of a fable.

The concreteness of the film is what remains with you: the texture of bark, the detail of peeling plaster in the manor house. The play of light through the forest. Visually, it’s one of the rare movies that makes you forget you’re watching a work of artifice; the sense of immersion in a place and time is so complete you never doubt it. You never think a wolf running through the woods is trained, never wonder about computer imagery or camera trickery. It’s like a documentary in its sense of an absolute reality, then, but still filmed with the beauty and attention to detail of worked art. It’s a beautiful movie, and engagingly complex in the way it folds stories into stories. Myths cross here; peasants take communion, and hold the wafer in their mouths to reuse in magic hunting charms. November lives, I think, in the tension of these things — the everyday, the physical, the earthy; and the ideal, the soul, the beautiful and poetic.

After that movie came Tokyo Idols. It’s a documentary about singers, fans, gender, and systems. In Japan, ‘idols’ are young women celebrities, media personalities worshipped by devoted and mostly male audiences. There are roughly 10,000 idols, most in their late teens or (very) early twenties, though some are as young as nine. Tokyo Idols follows one of these idols, 19-year-old Rio Hiiragi AKA RioRio, as she struggles to develop her career. It also follows her fans, such as 43-year-old Koji, the leader of her fan club. We see both the idol life and the life of the devoted follower. On the one hand, a young woman who crafts an upbeat, determined persona on social media and in live performances; on the other hand, a middle-aged man spending all he has to support his obsession.

After that movie came Tokyo Idols. It’s a documentary about singers, fans, gender, and systems. In Japan, ‘idols’ are young women celebrities, media personalities worshipped by devoted and mostly male audiences. There are roughly 10,000 idols, most in their late teens or (very) early twenties, though some are as young as nine. Tokyo Idols follows one of these idols, 19-year-old Rio Hiiragi AKA RioRio, as she struggles to develop her career. It also follows her fans, such as 43-year-old Koji, the leader of her fan club. We see both the idol life and the life of the devoted follower. On the one hand, a young woman who crafts an upbeat, determined persona on social media and in live performances; on the other hand, a middle-aged man spending all he has to support his obsession.

Both Rio and Koji become useful lenses through which to examine the idol phenomenon. There are no interview questions, no interactions with the off-camera interviewer, no narration, no facts and figures. There are other interview subjects besides those two, notably researchers analysing and criticising the idol industry; feminist scholar Minori Kitahara makes an especially strong case against the idols, and also discusses the backlash she’s received for her critique of the industry. But at the centre of the documentary are the two people locked in a symbiotic relationship and yet oddly distant from each other: the performer and her audience.

There’s an awful lot going on in Tokyo Idols, much to do with gender, with performance, with social roles. One might wonder to what extent the story being told is specific to Japan. Personally, as a western viewer, I’d say that while this is a Japanese story, there are applications on a much broader scale. But even if that’s so, then to what extent is a non-Japanese audience invited to view the idols as a creation of Japanese culture, and so to view Japan as uniquely strange? I don’t normally quote from a movie’s press kit, but perhaps it’s worth doing so in this case; according to the filmmakers,

We wanted to have a critical look without judging negatively from a western point of view. It was surprising for us how quickly our initial sense of creep went away. After a few concerts, a sense of normalcy kicked in. Idol scenes are not seedy and we never saw a drunken person even though the venues often sold alcohol. It’s actually very orderly and there is an unwritten rule of conduct. So for us, going back and forth between Japan and UK/Canada, was in fact, apart from logistical nightmares, very helpful. The physical distance helped us to restore our psychological distance and to keep remembering how uncomfortable we felt at the beginning while constantly asking ourselves how much we can accept and [sic] culturally sensitive while retaining our critical perspective? This balancing act was perhaps the trickiest part.

I think this comes out in the film. I found myself reflecting while watching that a lot of the aspects of the idol obsession, taken individually, are not without parallels in the west. Boy bands are a gender (and to an extent age) flipped version of the idols. And middle-aged men in the west may be obsessive followers of certain males in their late teens and early twenties, who happen to be good at athletics — I’m 44, and I follow the teenagers my favourite hockey team’s drafted or might draft. We’re told about a hugely famous idol group, AKB48, who have public elections for their members and televised specials; it doesn’t sound that different from certain media events in the west.

All that said, there is a sense that this is a distinctively Japanese story. One analysis discusses the increasing interest of men of a certain generation for the young idols as a function of the experience of that age cohort, a group suffering from an economic collapse. The idols of today’s Tokyo, with their uptempo pop, are compared to the punks of the 1970s’ London. It sounds strange, at first blush, in that these musical forms have no obvious point of similarity, and the clean-cut images of the idols with their conscious media-savvy are a long way from the original punks. But to hear the fans talk about their idols is to see the connection: as one observer comments, the men see themselves as in some way fighting alongside the idols against ‘the establishment.’

All that said, there is a sense that this is a distinctively Japanese story. One analysis discusses the increasing interest of men of a certain generation for the young idols as a function of the experience of that age cohort, a group suffering from an economic collapse. The idols of today’s Tokyo, with their uptempo pop, are compared to the punks of the 1970s’ London. It sounds strange, at first blush, in that these musical forms have no obvious point of similarity, and the clean-cut images of the idols with their conscious media-savvy are a long way from the original punks. But to hear the fans talk about their idols is to see the connection: as one observer comments, the men see themselves as in some way fighting alongside the idols against ‘the establishment.’

At the same time, the portrait of the fans is not pretty. They spend too much on the objects of their obsessions, are often alone, are even alienated from their families by their fixation. We are given a detailed discussion of what ‘otaku’ means here, and it’s not the simple equivalent to ‘fan’ or even ‘nerd’ that many westerners seem to think — there’s more social alienation, more creepiness. This explains and informs the connection of performer and fan. At its best, it fosters a sense of mutual empowerment created by the fandom, but at its worst there’s something much more disturbing going on. Typically the only contact between the fan and the performer comes in the form of post-show meet-and-greet handshake lines, and this seems normal enough until one analyst observes that, in a society that traditionally had strict limitations on contact between the sexes, the handshake had a definite sexual connotation.

There are security guards at these meet-and-greets, and there’s a sense in the film that the idols are kept as it were curated; that they’ve been provided a safe venue in which to experiment with displays of their sexuality. But only up to a point, and only in certain limited ways. They have a power, but mainly as a mirror for their fans; one of the limitations of the film is that it doesn’t explore the handlers and hierarchy behind Rio and other idols. In any event, when Rio says at one point that “My fans are like my children,” there’s no doubt she means it, and the image of a young woman speaking of men twice her age as her children perfectly brings out the odd emotional texture the film’s exploring. Much of the rest of the documentary points up the directness of the analogy. And this doesn’t take into account the younger idols — teen idols younger than Rio, pre-teen idols younger than that, all performing to crowds of fixated adult men.

There are security guards at these meet-and-greets, and there’s a sense in the film that the idols are kept as it were curated; that they’ve been provided a safe venue in which to experiment with displays of their sexuality. But only up to a point, and only in certain limited ways. They have a power, but mainly as a mirror for their fans; one of the limitations of the film is that it doesn’t explore the handlers and hierarchy behind Rio and other idols. In any event, when Rio says at one point that “My fans are like my children,” there’s no doubt she means it, and the image of a young woman speaking of men twice her age as her children perfectly brings out the odd emotional texture the film’s exploring. Much of the rest of the documentary points up the directness of the analogy. And this doesn’t take into account the younger idols — teen idols younger than Rio, pre-teen idols younger than that, all performing to crowds of fixated adult men.

One of the things Tokyo Idols does is to consider the limits of fandom. There’s a line between being a fan of something, and being obsessive about it; to say nothing of the question of whether it’s appropriate to be a fan of something in a way that’s inappropriate. Tokyo Idols opens up questions about all these things. And more: what, at heart, is fandom? For the men in Tokyo Idols, fandom is related to a need for heroes. And if there needs to be a justification for covering this movie on this website, there it is: this is, in a very real way, a movie about heroes. That’s the nature of fandom, exalting the object of worship into a hero and role model. The nature of being an idol, it’s clear, involves the conscious creation of an image of heroism. But to what extent is it healthy to be either hero or hero-worshipped? Tokyo Idols is a thoughtful, thorough, and oddly empathic look at the people in both roles.

After the film, director Kyoko Miyake came out to take questions from the audience. The first came from the Fantasia master of ceremonies, who noted that Miyake was born in Japan and lived there for some time before moving to the UK for university; given how much of the film had to do with being a woman in Japan, what motivated her in making it? Miyake said that she’d felt awkward as a girl growing up, and didn’t realise things could be otherwise until she went abroad for her studies in her early 20s. When she went back to visit her family, she became aware of the idol phenomenon, and the sense of awkwardness returned. She views the idol industry as a microcosm of Japanese society, and the way in which she finds women are trained to compete for male attention. Miyake said that she didn’t notice this until she lived abroad; she said she’s still undoing the programming she grew up with, and so this film was a very personal project.

After the film, director Kyoko Miyake came out to take questions from the audience. The first came from the Fantasia master of ceremonies, who noted that Miyake was born in Japan and lived there for some time before moving to the UK for university; given how much of the film had to do with being a woman in Japan, what motivated her in making it? Miyake said that she’d felt awkward as a girl growing up, and didn’t realise things could be otherwise until she went abroad for her studies in her early 20s. When she went back to visit her family, she became aware of the idol phenomenon, and the sense of awkwardness returned. She views the idol industry as a microcosm of Japanese society, and the way in which she finds women are trained to compete for male attention. Miyake said that she didn’t notice this until she lived abroad; she said she’s still undoing the programming she grew up with, and so this film was a very personal project.

Asked about how she decided on the form of the film and what she felt to be fair, she said that she’d originally planned to follow three up-and-coming girls, but quickly noticed that the idols were only half the story. She realised she had to look at the fans. At first she was reluctant, having various prejudices about them, but now she feels she has a better understanding of them and the desperation underlying their fandom. She spoke about their sense of betrayal, having grown up in an economic bubble that’s since burst, leaving them with a sense of betrayal and disillusionment.

Asked what was next for Rio, Miyake said she was still performing, but noted that it was hard to judge how successful she was, as an idol needs to create the illusion of always-increasing success. Strategic use of social media was key. Rio herself was between the underground and the mainstream, still active and her fan club still going — though Koji had gone bankrupt. Asked why there seemed to be no female fans of the idols, Miyake said that she did actually interview some but found in editing the film that their stories weren’t contributing to the central story she was telling. She said most were aspiring idols themselves, and Rio in fact had a higher proportion of female fans than was typical; some concerts literally were 99 percent male. Miyake said that in such a largely male atmosphere, girls tended to stick together, and in fact were given special sections — men didn’t want women around.

Miyuke was asked how fans reacted to a documentary filmmaker asking them hard questions on camera about their idols, and she said some were suspicious; but then again, some were suspicious of women their age in general. She tried to be honest about her intentions with them, and found that many had a kind of self-deprecating humour; after she explained the idea of the documentary to one of them, he said “so, your film is about how hopeless Japanese men are.” She noted that the atmosphere was different at the concerts of the nine-year-old idols, saying “Even for Japan, that’s weird.” She found she was greeted with accordingly more suspicion.

Miyuke was asked how fans reacted to a documentary filmmaker asking them hard questions on camera about their idols, and she said some were suspicious; but then again, some were suspicious of women their age in general. She tried to be honest about her intentions with them, and found that many had a kind of self-deprecating humour; after she explained the idea of the documentary to one of them, he said “so, your film is about how hopeless Japanese men are.” She noted that the atmosphere was different at the concerts of the nine-year-old idols, saying “Even for Japan, that’s weird.” She found she was greeted with accordingly more suspicion.

Asked what happens when a fan’s idol ‘graduates,’ she said there is an actual graduation ceremony for the idol, at which fans cry their eyes out. They then find a younger idol and begin a new fandom. The former idols, meanwhile, go on to regular jobs; there’s no stigma in having been an idol.

Miyuke was asked if she believed the fans of the younger idols who denied any sexual element surrounding the idols, and she observed that in her interviews she’d found a difference between idols ages about nine and those aged about fourteen. The younger ones didn’t distinguish between male and female adults, and spoke to her just as they spoke to their fans. The fourteen-year-olds were discovering their sexuality, and their approach was different. The nine-year-olds enjoyed the attention, were whisked out of venues by their handlers after events were concluded, and generally were too young to really understand events around them.

That ended the questions, and I headed home. It had been a fascinating day, with these two films and 78/52. It was hard not to ask myself questions about my own experience of film and what I had seen in fan communities, especially considering that I’d also seen Welcome to Wacken which spoke directly to a fandom of my own. There was at least one more film I planned to see at the festival dealing with similar issues. The next day, though, I’d end up seeing a movie that dealt with obsession and idealism in a quite different way.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.