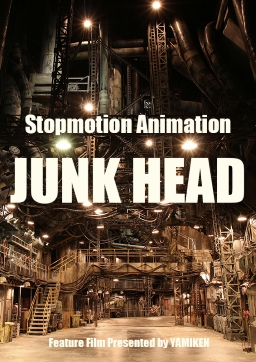

Fantasia 2017, Day 12: Junk Head

I had two events on my Fantaisa Festival schedule for Monday, July 24. First, I planned to see a stop-motion film from Japan called Junk Head. Then, I’d go to see a presentation by author Grady Hendrix of his book Paperbacks From Hell, about the boom of horror paperbacks in the 70s and 80s. I’d end up speaking briefly with Hendrix after his presentation, which led to my interviewing him for Black Gate; you can see that interview here. So in this post I’ll be talking about Junk Head, an astonishing achievement in science-fiction that well deserves an article to itself.

I had two events on my Fantaisa Festival schedule for Monday, July 24. First, I planned to see a stop-motion film from Japan called Junk Head. Then, I’d go to see a presentation by author Grady Hendrix of his book Paperbacks From Hell, about the boom of horror paperbacks in the 70s and 80s. I’d end up speaking briefly with Hendrix after his presentation, which led to my interviewing him for Black Gate; you can see that interview here. So in this post I’ll be talking about Junk Head, an astonishing achievement in science-fiction that well deserves an article to itself.

Junk Head was written and directed by Takahide Hori, who also edited the film, created the soundtrack music, and handled sound effects. He also, with only one or two others (principally Atsuko Miyake), animated the film, did the voice work, and made the puppets and props and sets. By any measure the film’s an accomplishment, and as a near-one-man labour of love, it’s spectacular. Hori uploaded an early version of the film, when it was a half-hour long, to YouTube; you can see it here. The version I saw at Fantasia went on for another hour and 24 minutes, and whether he ends up adding more to it or not — I heard different things, all at second- or third-hand — it tells a complete story. (Thanks to a heads-up from Sandro Forte of Cinetalk.net, I can add that Hori and his team are working on a prequel they’re funding through Kickstarter; I strongly recommend checking the campaign out.)

Title cards at the start of Junk Head give us the background: it’s the far future, when human beings have become effectively immortal by making their bodies inorganic, but as a result cannot reproduce. And now a terrible plague is striking down the world’s population. There’s only one hope. Someone has to be sent into the abysses upon which this future civilization’s built, a labyrinth of tunnels and spaces long since abandoned to clones once used for labour. In the centuries since, the clones have mutated in strange ways, and built their own cultures among the concrete of the lower levels. To save humanity, genetic material from the clones has to be recovered — but how to get genetic material from the seemingly sexless clones? And how are beings not designed to reproduce accomplishing the feat, anyway?

The protagonist of the film has no name. After the first few minutes they’re blown to bits by a clone’s rocket, but their head survives. Another group of clones cobbles together a new body for the protagonist, who begins to search for answers. And stumbles on monsters, clones horribly mutated into utterly inhuman things. Our hero gets lost, loses their body, is reconstituted, loses their memory, and wanders through the vast concrete realms of the clones.

The protagonist of the film has no name. After the first few minutes they’re blown to bits by a clone’s rocket, but their head survives. Another group of clones cobbles together a new body for the protagonist, who begins to search for answers. And stumbles on monsters, clones horribly mutated into utterly inhuman things. Our hero gets lost, loses their body, is reconstituted, loses their memory, and wanders through the vast concrete realms of the clones.

There are some interesting themes at work. The human’s compared to a god by at least some of the clones, and the ultimate quest-object turns out to be a literal tree of life. If there’s a religious parallel, it can be read in a number of ways — a harrowing of hell, or god descending into fallen creation to be saved by the god’s own creation. It could challenge the idea of a meaning to life, or it could be seen to celebrate it.

But the immediate impact of the film is certainly visual. It’d hard not to think of Tool’s videos when watching it. There’s a constant grittiness to the movie, and a kind of subliminal feel of desolation and disturbance. That’s because it takes place in an enclosed industrial wasteland, brutalist concrete everywhere, a palette entirely of greys and browns and yellows and blacks with some red highlights. Rather than being dull, though, it’s horrific. As though the absence of conventionally living things, of anything green at all, has made a particularly sterile hell. And the fact that there are monsters around every corner and down every crevice doesn’t hurt.

The monsters are apparently grossly warped clones, and what is truly disturbing about them is the sense, in most cases, that they’re distortions of the human form. They’re utterly nightmarish, threatening on an almost instinctive level, not simply as big scary things but as things that tap into deep aversions. You can’t help but think of Giger and the xenomorph of Alien, except rather than one form we see endless variations of monstrosity.

The monsters are apparently grossly warped clones, and what is truly disturbing about them is the sense, in most cases, that they’re distortions of the human form. They’re utterly nightmarish, threatening on an almost instinctive level, not simply as big scary things but as things that tap into deep aversions. You can’t help but think of Giger and the xenomorph of Alien, except rather than one form we see endless variations of monstrosity.

Yet and at the same time there’s a kind of sublimity in this underworld. The endless narrow corridors occasionally open out into vast abysses and cathedral-like spaces. The scale opens out and closes in, cyclopean and claustrophobic by turns. And in its way constantly science-fictional. These are clearly abandoned industrial areas. The omnipresent concrete is a signifier of artificiality, nature evident in its total absence. Even when we don’t see machinery — clunky, mechanical, tactile machinery — we know that we’re seeing a vision of the future, a kind of inspired post-apocalypse dream. The first images of the film emphasise this: the human explorer’s sent off in a rocket which instead of launching upward is let drop downward. The science-fictional hope for the future’s inverted.

For most of the film, the human protagonist wanders the realms of the clones, and part of the fascination of the movie is simply exploration: seeing how societies fit together, and how the various residents cope with monsters wandering about in their living spaces. We see people co-operate, we see hierarchies, we see con-men. If there’s a lot of brutality in this desperate environment, there are also faithful workers upon whom the whole structure depends. And there are moments of fairy-tale beauty.

For most of the film, the human protagonist wanders the realms of the clones, and part of the fascination of the movie is simply exploration: seeing how societies fit together, and how the various residents cope with monsters wandering about in their living spaces. We see people co-operate, we see hierarchies, we see con-men. If there’s a lot of brutality in this desperate environment, there are also faithful workers upon whom the whole structure depends. And there are moments of fairy-tale beauty.

If the discovery of these things is episodic, it’s also unpredictable. Things tie together nicely at the end, though that ending’s unexpectedly abrupt. I think there’s a valid complaint to be made that a certain piece of information about a companion the protagonist finds is given too quickly — I literally blinked and missed it, only having it pointed out to me by another critic discussing the film afterward. I can imagine other people finding the various parts of the film disjointed or episodic, and I suspect the protagonist’s extended bout with amnesia will frustrate viewers looking for a constant forward movement in the main plot.

But the animation’s excellent, the visuals constantly inventive, and there’s a coherence that pays off with a left-field resolution for careful viewers. This is a dystopian fairy-tale that speaks to the future and the present in its own idiosyncratic language. It’s unpredictable, intelligent, and compellingly hallucinatory. To me, Junk Head is a tremendous achievement, a stunning if nightmarish science-fiction saga.

But the animation’s excellent, the visuals constantly inventive, and there’s a coherence that pays off with a left-field resolution for careful viewers. This is a dystopian fairy-tale that speaks to the future and the present in its own idiosyncratic language. It’s unpredictable, intelligent, and compellingly hallucinatory. To me, Junk Head is a tremendous achievement, a stunning if nightmarish science-fiction saga.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.