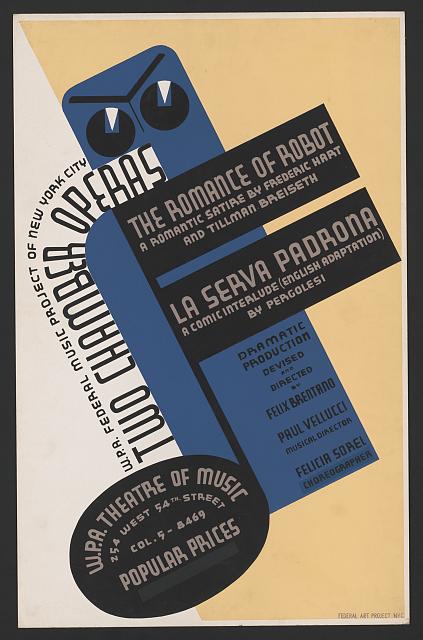

The Romance of Robot

Franklin Roosevelt had only one true ideology during the Great Depression: try it, maybe it will work. The range of innovative,productive, uplifting, unworkably idealistic, and just plan crazy plans had something for everybody to love and to hate. Federal Project Number One exemplified these extremes.

FPN1 devoted itself to the radical idea that creatives were human beings deserving of dignity and of meaningful work inside their professions. And to the even more radical idea that it would hire qualified minds without discrimination regarding race, creed, color, religion or political affiliation. Over the few years from its start in 1935 until World War II the creatives of FPN1 created lasting monuments of American culture.

Although names mutated rapidly, as Roosevelt’s alphabet agencies were wont to do, most people have probably heard the usual titles of FPN1’s subgroups, The Federal Writers Project, the Federal Art Project, the Federal Theater Project, and the Historical Records Survey. Perhaps least known is the Federal Music Project (FMP), which concentrated on highbrow performances of original music, as guaranteed a portent of ephemerality as can be found in American culture.

They tried, to be sure. Operas were often cut short to a single act and the libretto sung in English to be sure audiences understood. Not always a good idea. I’m positive that some lyrics would have seem far more imposing in German, or Italian, or Esperanto. Like these:

We adore you, man of steel

We admire the way you feel…

Humbly at your foot we kneel;

We adore you, man of steel!

(You can sing that to the tune of “We Love You, Beatles” if you interpolate the “oh, yes we do.”)

The epithet “man of steel” is found in Shakespeare – Marc Antony calls himself one in Antony and Cleopatra, Act iv, Scene iv. The comic book Superman is another year off. This man of steel is a literal one, the title character of The Romance of Robot, premiered April 12, 1937.

Composer Frederic Patton Hart taught in the music faculty at Sarah Lawrence, librettist Tillman Kermit Breiseth was a playwright. Together they wrote a one-act operatic satire about the machine age’s lack of soul. A contemporary review in the Barnard College student newspaper gives a wonderful summary:

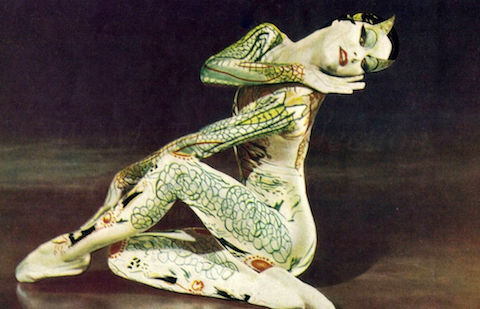

The Romance of Robot (a Sentimental Satire) is somewhat similar to Buck Rogers of the funny-sheets, with sound effects and without rocket ships. Electro, master of an electrolyzed age, a modern Caesar, has created Robot, the perfect man with alternating and direct current, and aluminum joints. But when the master’s electrolyzed ladies [named Switch, Piston, Spark, Gear, and Klaxon: has any tale involving robots ever been described as subtle?],who formerly trembled at his coming, ladies as feminine as ever beneath their angular costumes, meet Tiny Tim, “a passionate believer in the romantic past”, they are convinced that Robot is incapable of emotion. In protest, they hold a rhythmic sit-down strike until Electro promises to prove the existence of a soul in his mechanical man. In desperation, he gives his soul to Robot, thus losing the love of his Cylindra, “the perfect modern beauty.” Yet to all of Cylindra’s sinuous glitter, Robot answers in a tiny voice, “You bore me.” It is up to Philomela, “a wandering song-bird,” in lace ruffles and a lavender parasol, to arouse him. Due to her song, the spell (for there seems to have been one) is broken, and he emerges, a full-grown young man, from his steel encasement. The opera ends in a whirl of chiffon, valentines and paper doves; Tiny Tim is justified, and every lady has her beau.

Tales of Hoffmann

For all the classical trappings that hark back to Offenberg’s Tales of Hoffmann (in which a young student is bewitched by a gorgeous female automaton glimpsed in a workshop), The Romance of Robot has myriad contemporary reflections. The most famous robot in the world in 1937 was Willie Vocalite, a robot built to tout Westinghouse’s appliances, one that appeared at the 1933 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition and toured the country to department stores and other appliance dealers in his personal Williemobile. Willie could talk, sing, move, smoke, and obey, said the ads. Moreover, “He has No Soul! No Heart! No Brain!/He’s a Scientific Marvel!” If that were the technological present and undoubtedly the future as well, no wonder that critics of modernism decried the dangerous power of the machine age and that Breiseth gave the ladies the lament:

We have cast off human ills,

Silly pastimes, Paris frills.

Pledged to work without cessation,

Polishing a steel creation.

Ask any of the science fiction writers of the day; emotions are fatal to robots. The rationalized world is no match for humanity, whose heart and soul cannot be replicated by machines unless they transcend their steel cages. As music historian Kenneth J. Bindas writes, Robot and Philomena are “liberated by their love,” freed to enter a soft and silky human world superior to polished steel:

Love’s born of sounds that are lush.

Surrounded by satin, laces, and plush,

Love grows on words such as Darling, Honey, Sweetheart,

True love is mentally dense.

Reviews were decidedly mixed, with Hart’s score getting the worst of it. Bindas says, “Machine sounds, bells, sirens, buzzers, and other noises were mixed into a music best described as frenetic did little to enamor The Romance to the FMP’s national staff.” The Federal Music Theater in Manhattan ran performances for at least a month and Hart presented a few orchestra-only events in other cities but audiences undoubtedly preferred getting their farcical robots from movie serials with Flash Gordon and Crash Corrigan, heroes whose brows were low and covered brains undoubtedly mentally dense.

Steve Carper writes for Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was The First Three Laws of Robotics.