The First Three Laws of Robotics

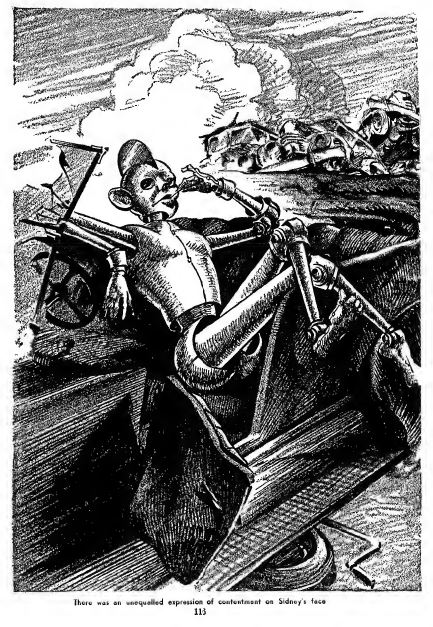

Sidney, the Screwloose Robot, illustration by

Julian S. Krupa (Fantastic Adventures, June 1941)

Who first came up with three laws of robotics? Want three guesses? Try. Isaac Asimov? No. John W. Campbell? No. William P. McGivern? Yes. William P. McGivern? That seems impossible, but there it is in black and white. “You must be industrious, you must be efficient, you must be useful. Those are the three laws that are to govern your behavior.”

McGivern was only 21 when in 1940 he became one of Ray Palmer’s house writers for Amazing and Fantastic Adventures. In-house writers, really, for he shared an office with David Wright O’Brien at the Ziff-Davis Chicago headquarters. Thirty-five of his stories appeared under various names in those two magazines in 1941, along with a picture that makes him look about twelve.

Buried deep in the June 1941 issue of Fantastic Adventures lay “Sidney, the Screwloose Robot,” part of the plague of farcical stories Palmer demanded and often titled. (Others from McGivern in 1941: “The Quandary of Quintus Quaggle,” “Al Addin and the Infra-Red Lamp,” and “Rewbarb’s Remarkable Radio”)

Robot stories were standard fare in the pulps. I count at least 70 from the founding of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories through June 1941. McGivern knew the field well and played off his predecessors. Sidney,

…looked like one of those illustrations you see in science fiction magazines. You know the kind… robots with jointed arms and legs, cylindrical steel bodies and bucket-like heads…

Short on cash, the inventors need to win the prize at the forthcoming science convention to pay their bills. All Sidney needs to do is follow the three laws and work for his keep.

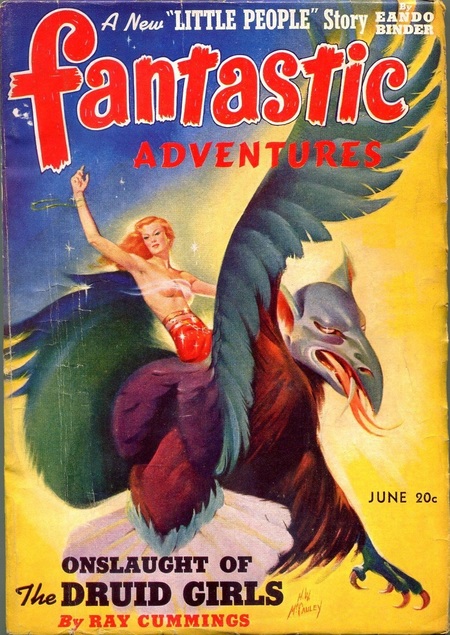

Fantastic Adventures, June 1941.

Cover by Harold W. McCauley

Sidney reacts to the mention of work about the way Maynard G. Krebs would. He’s the world’s laziest robot. Threats, bribes, and cajolery all fail to sway him. He seems to have a screw loose. Literally. They find it on the floor instead of inside Sidney’s brain. With no time to rebuild him before the convention, things couldn’t get worse and of course do. Sidney gets oiled up. That’s 1940s slang for drunk and also literally true. Drinking a gallon of penetrating oil makes his gears run at triple speed. (That’s an … interesting design choice.) He sees pink can openers. (Could Henry Kuttner have read this before writing his 1943 masterpiece, “The Proud Robot”?) Asimov would become famous through a series of stories in which his Campbellian troubleshooters have to fix malfunctioning robots but McGivern would never consider an engineering solution. The inventor’s beautiful sister visits and Sidney falls in love. He would do anything for her, even work. Until he gets drunk again.

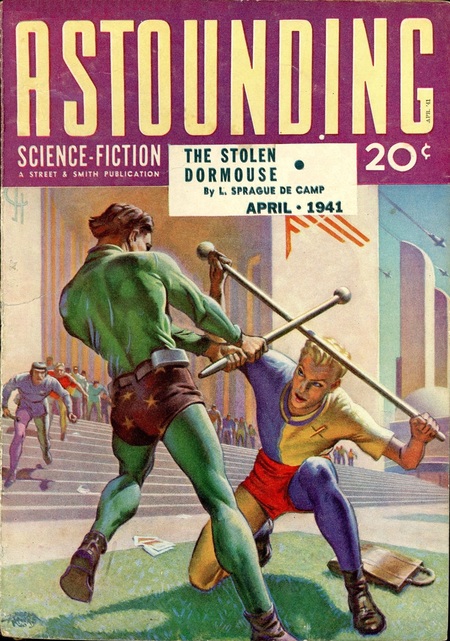

Astounding Science-Fiction April 1941, containing

Asimov’s “Reason.” Art by Hubert Rogers

Asimov introduced his First Law of robotics in “Reason,” Astounding Science-Fiction April 1941. McGivern and O’Brien had the office at Amazing so that they could fill empty space at a moment’s notice but getting a story in print in a mere two months after reading the April Astounding seems highly improbable. Even if they hurried it in, that’s almost a year before Asimov codified his Three Laws in “Runaround,” Astounding Science-Fiction March 1942. Campbell is usually given credit for telling Asimov to expand his First Law into three. I might make the heretical suggestion that Campbell, checking out the competition, did so after noticing McGivern’s story. Equally possible is that Asimov did. He was a voracious reader of f&sf and adapted older ideas into many of his early stories.

McGivern became a newspaper police reporter after the war and most of his later output was in mysteries, several of them adapted as films. He moved to Los Angeles and started a prosperous career as a television and movie writer. Since he never wrote a true SF novel, his name has mostly been forgotten. So has “Sidney, the Screwloose Robot.” I can’t find a hint of anyone noticing the first ever example of the three laws hidden inside it despite my scouring the Internet. If I’m first, you now have a sure winning bar bet. Have a drink on William McGivern, inventor of the Three Laws of Robotics.

Steve Carper writes for Digest Enthusiast. His story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com.

Thanks for this industrious, efficient, and useful article.

I’ll have to check his work out. I recently inherited a box of crumbling old sci-fi pulps and was surprised to see the name of the author of The Big Heat keep coming up in the contents pages.

That’s a bit of a windfall Andy. You should do a post if you find any special treasures amongst the mouldering pages.