Hit That Word Count! Reading The Fiction Factory by William Wallace Cook

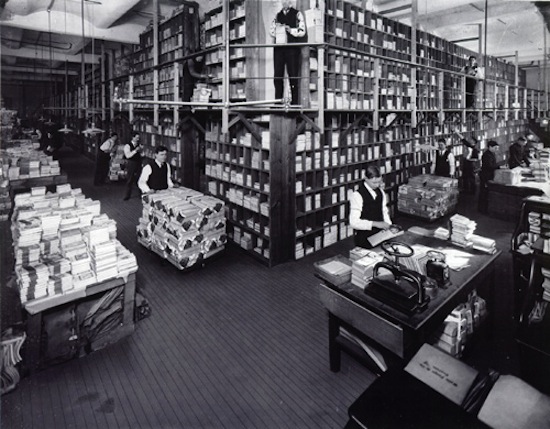

Street & Smith was one of the many publishers Cook worked for.

This is their book department in 1906, at the height of Cook’s career.

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, I’ve been studying the careers of hyperprolific authors. No study of the field would be complete without looking at the life of William Wallace Cook. Around the turn of the last century his work was everywhere — as serialized novels in newspapers, as dime novels, and later in hardback books. We wrote everything from boy’s fiction to romance to mystery to science fiction.

His two most enduring books, however, and really the only two that are still read today, are both nonfiction. The first is Plotto, a plot outline device that allows you to link up various plot elements to create a virtually infinite variety of stories. It’s on my shelf but I have yet to try it. The other is The Fiction Factory, in which he describes his early years breaking into the writing business in the 1890s and his climb to steady success in the early years of the 20th century. Despite having been written more than a hundred years ago it remains useful and inspiring reading for any aspiring or professional author.

Writing under the pen name John Milton Edwards, and referring to himself in the third person he boasts:

John Milton Edwards has, in a score and two years of work, wrested more than $100,000 from the tills of the publishers. Short stories, novelettes, serials, books, a few moving picture scenarios and a little verse have all contributed to the sum total. Industry was rowelled by necessity, and when a short story must fill the flour barrel, a poem buy a pair of shoes or a serial take up a note at the bank, the muse is provided with an atmosphere at which genius balks. True, genius has emerged triumphant from many a Grub Street attic, but that was in another day when conditions were different from what they are now. In these twentieth century times the writer must give the public what the publisher thinks the public wants. Although the element of quality is a sine qua non, it seems not to be incompatible with the element of quantity.

The title of his memoir is certainly appropriate. Cook churned out an impressive amount of work, often with a staff of up to three typists to whom he dictated. His mainstay was the nickel novel, a 30,000-word story for boys in newspaper format. These he wrote in three days or a week for an average of $50, at a time when the average income was around $450 a year. Cook was regularly making ten times that amount, or about the same as an experienced mechanical engineer.

But his career wasn’t without his ups and downs. Publishers would suddenly stop series, his royalties on books were consistently disappointing, and he spent years trying and failing to get his stories turned into theater productions. And then there’s perhaps the most brutal rejection letter of all time:

We are sorry to return your paper, but you have written on it.

That’s enough to make you throw your typewriter out the window!

It’s amazing just how much of his advice is still right on target for today’s writer. For example:

Jack London advises not to wait for inspiration but to “go after it with a club.” Bravo! It is not intended, of course, to lay violent hands on the Happy Idea or to knock it over with a bludgeon. Mr. London realizes that, nine times out of ten, Happy Ideas are drawn toward industry as iron filings toward a magnet. The real secret lies in making a start, even though it promises to get you nowhere, and inspiration will take care of itself.

There’s a lot of ‘fiddle-faddle’ wrapped up in that word ‘inspiration.’ It is the last resort of the lazy writer, of the man who would rather sit and dream than be up and doing. If the majority of writers who depend upon fiction for a livelihood were to wait for the spirit of inspiration to move them, the sheriff would happen along and tack a notice on the front door while the writers were still waiting.

More and more Edwards’ experience, and the experience of others which has come under his observation, convinces him that inspiration is only another name for industry.

HELL. YEAH. And then there’s this:

There is not a detail in the preparation or recording or forwarding of a manuscript that can be neglected. Competition is keen. Big names, without big ideas back of them, are not so prone to carry weight. It’s the stuff, itself, that counts; yet a business-like way of doing things carries a mute appeal to an editor before even a line of the manuscript has been read. It is a powerful appeal, and all on the writer’s side.

Of course, sometimes details in the stories are missed: “W. Bert Foster, a friend of Edwards’, who for twenty-five years has kept a story-mill of his own busily grinding with splendid success, has this to say about a slip he once made in his early years:

When I was a young writer I sold a story to a juvenile publisher. It was published. And not until the boys began to write in about it did either the editor or I discover that I had my hero dying of thirst on a raft in Lake Michigan!

I am proud to say that I have never made that big of a mistake in my fiction. At least I hope not. Perhaps “the boys” aren’t as accustomed to writing letters as they were back in Edwards’ day.

And finally, here’s perhaps the most important advice for any writer:

No matter what you are writing, unless you can thrill to every detail of excellence in what you do, unless you can worry about the obscure sentence or the unworthy incident until they are sponged out and recast, it is not too much to say that you will never succeed in the writing game. Love the work for its own sake and it will bring the inspiration and its reward; look upon it as a grind and a melancholy failure stalks in your wake.

The Fiction Factory can be downloaded for free in various formats from archive.org.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page. His latest book, The Case of the Purloined Pyramid, is a neo-pulp detective novel set in Cairo in 1919. It’s currently a candidate in the Kindle Scout program. If you nominate it and it wins, you get a free copy!

You were right about the advice being as good today it was 100 years ago.