October Is Hammer Country: The Curse of the Werewolf (1961)

On the second week of October, Hammer Films gave to me … one Oliver Reed werewolf, and I guess that’s all I need.

On the second week of October, Hammer Films gave to me … one Oliver Reed werewolf, and I guess that’s all I need.

By 1961, the Gothic horror machine at Hammer Film Productions had unleashed Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Mummy. Now partnered with Universal International and free to use the studio’s classic monsters, it was inevitable that Hammer tackled The Wolf Man next. Universal, however, purchased the rights to Guy Endore’s 1933 novel The Werewolf of Paris and asked Hammer to adapt that. Instead of a Hammerized version of the tragedy of Lawrence Talbot, we got a much different type of lycanthrope movie, The Curse of the Werewolf. Which is fine, because The Curse of the Werewolf is pretty darn great. Director Terence Fisher and the production team working out of Bray Studios were in peak form, and Oliver Reed, in his first starring role, ripped ferociously into a part so suited to his talents that it feels like the start of a comedy bit.

There was no feasible way for Hammer to make a straight adaptation of The Werewolf of Paris on a $100,000 budget. Producer Anthony Hinds was stunned when he first read the novel to discover epic scenes of warfare and street fighting in the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. With no money to hire a screenwriter, Hinds took on the job himself, using the writing pseudonym “John Elder” for the first time, and looked for a way to squeeze a werewolf script into the budget. One cost-saving maneuver was relocating the story from nineteenth-century France to eighteenth-century Spain so the movie could be shot back-to-back on the sets for The Rape of Sabena, a Spanish Inquisition movie co-financed with Columbia. Hammer chairman James Carreras canceled The Rape of Sabena because of concerns raised by the British Board of Film Censorship, but the sets were already built, so The Curse of the Werewolf continued ahead with the Spanish setting. It would also run into grief with the BBFC; considering some of the sexually violent content, it’s amazing The Curse of the Werewolf made it through production while the Inquisition movie never got off the blocks.

Little of Guy Endore’s historical werewolf epic and its heavy political themes made it into The Curse of the Werewolf. Hinds’s screenplay retains the novel’s origin story of its doomed protagonist, but otherwise fashions an original story restricted to the limited sets. What The Curse of the Werewolf does manage to capture, perhaps better than any other Hammer horror film, is the feeling of a classic era Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto-to-Melmoth the Wanderer period of the late-18th and early 19th-centuries. The setting is Catholic Southern Europe, there are curses and madmen and rape and dungeons and corrupt aristocrats and ominous portents. It’s churning and boiling with the influence of Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis, and Charles Maturin — just minus the overt anti-Catholicism. A scene where the baptism of a child born under unlucky stars causes the waters of the baptismal font to tremble and a sudden lightning storm to break out is worthy of the best of the Gothic originals.

This mass of Gothic influences, creating a compressed epic, allows The Curse of the Werewolf to work as great horror entertainment even though the werewolf slaughter action doesn’t start until an hour into a 93-minute film, and the full werewolf makeup is only revealed ten minutes before the words “The End” appear.

The movie breaks into three distinct sections with the passage of years between them. The first part is an extended prologue telling the origin of the werewolf curse, and it contains some of the most horrifying and purely Gothic material Hammer committed to film during their golden era.  Unlike the familiar lycanthropy story, the curse isn’t transmitted through the bite of another werewolf. Rather, it’s the result of a chain of horrible events beginning with a wandering beggar (Richard Wordsworth) forced to humiliate himself before a sadistic marques (Anthony Dawson, who later played Professor Dent in Dr. No) when the beggar comes to his castle door during the marques’s wedding feast. The beggar is hurled down into a dungeon cell, forgotten for years until he becomes an insane, near-animal creature. The widowed, friendless marques — now basically a walking skin-disease in Ebenezer Scrooge cosplay — locks a mute servant girl (Yvonne Romain) who spurned his advances into the dungeon with the crazed beggar, who rapes her and then dies. The marques releases the girl, and she promptly stabs him to death with an iron torch sconce and flees the castle. She dies giving birth to her baby on Christmas Day, reputedly an evil omen for an unwanted child.

Unlike the familiar lycanthropy story, the curse isn’t transmitted through the bite of another werewolf. Rather, it’s the result of a chain of horrible events beginning with a wandering beggar (Richard Wordsworth) forced to humiliate himself before a sadistic marques (Anthony Dawson, who later played Professor Dent in Dr. No) when the beggar comes to his castle door during the marques’s wedding feast. The beggar is hurled down into a dungeon cell, forgotten for years until he becomes an insane, near-animal creature. The widowed, friendless marques — now basically a walking skin-disease in Ebenezer Scrooge cosplay — locks a mute servant girl (Yvonne Romain) who spurned his advances into the dungeon with the crazed beggar, who rapes her and then dies. The marques releases the girl, and she promptly stabs him to death with an iron torch sconce and flees the castle. She dies giving birth to her baby on Christmas Day, reputedly an evil omen for an unwanted child.

You can see why the censors may have raised a few objections to all this. And we haven’t even gotten within howling distance of the actual werewolf yet.

The second part of the movie follows the first emergence lycanthropy in the boy, Leon. The kindly scholar, Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans from The Kiss of the Vampire), who sheltered the servant girl has taken charge of raising the orphaned boy with the help of his dedicated housekeeper Teresa (Hira Talfrey). When Leon’s werewolf nature starts to manifest itself, they find a way to suppress the curse through the power of their loving household. The movie’s final and longest part has an adult Leon (Oliver Reed) leaving home to try to make his way in the world. It doesn’t take long for his full werewolf side to re-emerge, but there’s a chance his romance with a wealthy vintner’s daughter, Cristina Fernando (Catherine Feller), may stop it. Except Cristina and Leon’s love is forbidden by her father and … this doesn’t go well for anybody.

Director Terence Fisher had a fondness for the film because of the romance element and the concept of love suppressing the beast inside a man, a beast created originally from astounding cruelty. “I feel strongly that the character involvement and the interplay of emotions is greater in this film than any of the others I have directed,” Fisher said in a 1976 interview. “They are more important than the situations that the characters are placed in. Hell, anyone can turn into a werewolf, can’t they? But it was [Leon’s] situation that made it exciting. The horror of him knowing that this was happening to him and the conflict between this and his love for the girl.”

Fisher also gave plenty of credit to Oliver Reed, so it’s time to talk about that. Oliver Reed as a werewolf: it seems too on-the-nose, right? Reed was a familiar supporting figure in early Hammer movies; Fisher directed him the year before as a bouncer in The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll. Somebody noticed Reed’s bulky physical presence and dark charisma might be put to good use in meatier parts and promoted him to the lead in The Curse of the Werewolf and later in the contemporary thriller Paranoiac (1963), another Hammer film heavy with literary Gothic influences. Although Reed wouldn’t emerge as a full celebrity until Oliver! (1968) and his collaborations with Ken Russell, he already carries himself like a star in The Curse of the Werewolf. He’s a magnetic performer who demands attention whenever he’s on screen.

Reed, who could probably drink an Irish regiment under the table, was a natural choice to play a man torn by the constant urge to change into a rampaging, hirsute beast. He does not disappoint. The actor is intimidating even when relaxed, and as Leon starts to let rage boil over in him, such as in a remarkable scene in a rowdy tavern where he’s sweatily careening toward wolfing-out, Reed essentially turns into his own special effect. Although Catherine Feller provides nothing remarkable as Leon’s love interest Cristina, the combination of Reed’s passionate focus and Fisher’s direction emphasize how much Cristina’s gentility is necessary to suppress Leon’s beast curse. Feller’s delicate features also make an excellent visual contrast with Reed.

Reed, who could probably drink an Irish regiment under the table, was a natural choice to play a man torn by the constant urge to change into a rampaging, hirsute beast. He does not disappoint. The actor is intimidating even when relaxed, and as Leon starts to let rage boil over in him, such as in a remarkable scene in a rowdy tavern where he’s sweatily careening toward wolfing-out, Reed essentially turns into his own special effect. Although Catherine Feller provides nothing remarkable as Leon’s love interest Cristina, the combination of Reed’s passionate focus and Fisher’s direction emphasize how much Cristina’s gentility is necessary to suppress Leon’s beast curse. Feller’s delicate features also make an excellent visual contrast with Reed.

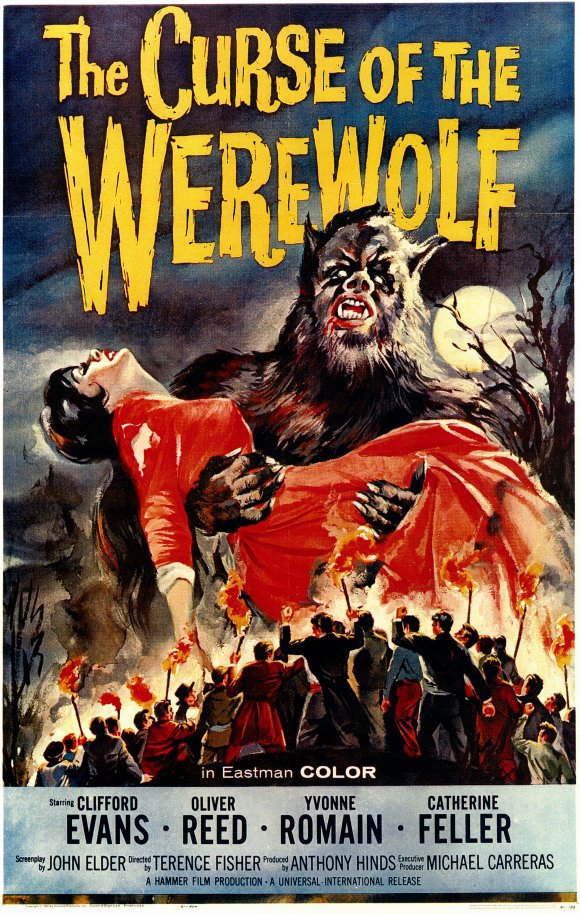

The full werewolf makeup finally appears when Leon transforms inside a jail cell. Even though the marketing material gives away the design, it’s still a thrill to see it emerge on screen. Makeup designer Roy Ashton, who did the impressive work on Christopher Lee for The Mummy, creates one of the great werewolf looks, making radical changes to the familiar Lon Chaney Jr. design (it’s far less simian) and adding more lupine touches such as large ears. The makeup is a natural fit for Oliver Reed’s features, which already lend themselves to monstrous transformations. The sight of this werewolf jumping around the roofs of Spanish buildings wearing a torn apart frilly shirt is what I call Grand Romance.

More than any of Hammer’s golden age horror films, The Curse of the Werewolf has risen in my estimation from when I first saw it. I once felt it was too dilatory and the long absence of the actual werewolf promoted on the posters bothered me. Now it feels perfectly paced for the fairy-tale Gothic atmosphere Terence Fisher aimed to create, and the amount of grisly material loading up the opening is early Hammer Films at their most outré. It’s a unique piece of lycanthropy cinema that avoids the werewolf-by-infection cliché for a powerful drama about a man turned into a monster through a legacy of hatred and violence, but who can be saved by a foster-father’s love. In the end, the emotional impact Fisher sought lands hard: Don Corledo must be the one to kill his adopted child, which is an admission he couldn’t save him through his love. That the gun he uses to do the job contains a silver bullet is only a detail.

By the way, if you’ve never read the novel The Werewolf of Paris, I highly recommend it — and it’s currently back in print.

The Curse of the Werewolf is currently available in North America on Blu-ray as part of Universal’s Hammer Horror 8-Film Collection, which includes last week’s subject, The Kiss of the Vampire. The source print appears to have been in better shape than the one used for Kiss of the Vampire, with a noticeable improvement in detail.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Sounds fascinating. Based on this article, I just bought the digital HD version off Amazon, and I will watch it tonight.

Wonderful review, Ryan.

I haven’t seen this film since a Detroit area horror show host showed it to me when I was a kid. So I’m following Amy to buy a copy right now.

Halloween, you gotta roll with it.

I have a friend who drops by once or twice a month for a little demented video, and he invariably wants to watch a Hammer. He’s fonder of them than I am (though I have a shelf full of them – of course), and we always look forward to any that feature Oliver Reed, whom we have fondly dubbed, “The Laurence Olivier of Utter Crap.”