Paperbacks From Hell: An Interview with Author Grady Hendrix

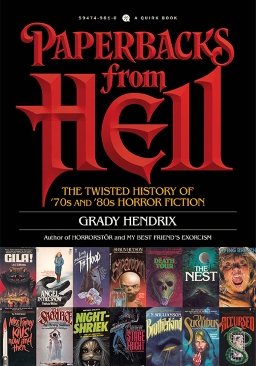

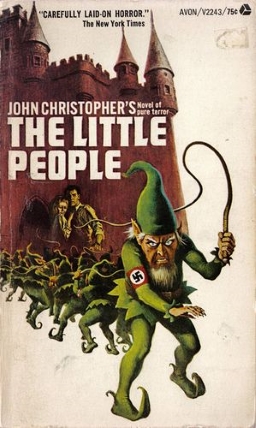

Grady Hendrix is a man who knows his horror. I saw him speak about horror paperbacks from the late 60s through the early 90s at the Fantasia International Film Festival, where he previewed his then-upcoming book Paperbacks From Hell. His passion and knowledge were clear at once. So was his wit — he clearly took these books seriously, but also knew when to take them lightly. His presentation was a powerful and slightly manic guide to a weird world of which I’d known nothing: a paperback world of mutilated dolls, of killer clowns, of diversely-talented skeletons, and, of course, of Nazi leprechauns. I had to know more about his book, and spoke with him after the show, asking if I could interview him for Black Gate. He agreed. Since then, Paperbacks From Hell has officially been published, and you can buy it now at Amazon.com. The book presents a striking new angle on horror fiction in the late twentieth century, and I hope the following interview further whets your appetite for Paperbacks From Hell.

Grady Hendrix is a man who knows his horror. I saw him speak about horror paperbacks from the late 60s through the early 90s at the Fantasia International Film Festival, where he previewed his then-upcoming book Paperbacks From Hell. His passion and knowledge were clear at once. So was his wit — he clearly took these books seriously, but also knew when to take them lightly. His presentation was a powerful and slightly manic guide to a weird world of which I’d known nothing: a paperback world of mutilated dolls, of killer clowns, of diversely-talented skeletons, and, of course, of Nazi leprechauns. I had to know more about his book, and spoke with him after the show, asking if I could interview him for Black Gate. He agreed. Since then, Paperbacks From Hell has officially been published, and you can buy it now at Amazon.com. The book presents a striking new angle on horror fiction in the late twentieth century, and I hope the following interview further whets your appetite for Paperbacks From Hell.

I’ll start at the beginning, I guess: How did the idea for the book develop? You write a bit about how you feel in love with horror paperbacks, but how did you get from collecting them to writing about them and publishing a book?

I’ve always been a reader, but my first huge enthusiasm was for movies. And in film fandom there’s a proud tradition of wandering out into the wilds and bringing back the most obscure and strangest films you can find. I didn’t see that tradition so much with books, and yet there were these vast used bookstores containing a wilderness of paperbacks, and all I wanted was a map so I could start exploring. Turns out I had to make one myself. Other people will do a better job, but I’m hoping I’ve given them a place to start.

The tone of the book impressed me, knowledgeable but light, mostly mocking while still loving, but shifting easily into a more serious register when talking about better books or heavier real-life experiences. How did you settle on or evolve that passionate-yet-irreverent tone?

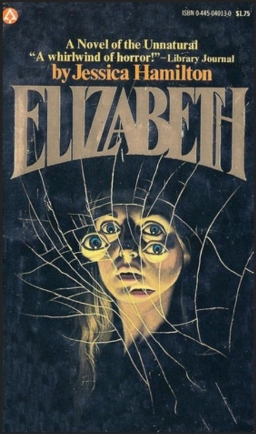

That’s just the way I write. I was a film critic for a long time and I believe that reviews should entertain and inform, in that order. You need to give people context for what they’re seeing if it’s older or from a tradition that we’re not used to seeing on a regular basis (I spent a lot of time writing about Asian film). Also, I don’t want to make judgments but there’s not much to say with a book like Stephen Gresham’s Abracadabra so it’s fun to use it as a jumping off point for a rant about my hatred of stage magicians. On the other hand, making fun of a really accomplished and moving novel like Bari Wood’s The Tribe or Ken Greenhall’s Elizabeth would be jackassery of the highest order.

That’s just the way I write. I was a film critic for a long time and I believe that reviews should entertain and inform, in that order. You need to give people context for what they’re seeing if it’s older or from a tradition that we’re not used to seeing on a regular basis (I spent a lot of time writing about Asian film). Also, I don’t want to make judgments but there’s not much to say with a book like Stephen Gresham’s Abracadabra so it’s fun to use it as a jumping off point for a rant about my hatred of stage magicians. On the other hand, making fun of a really accomplished and moving novel like Bari Wood’s The Tribe or Ken Greenhall’s Elizabeth would be jackassery of the highest order.

Paperbacks From Hell is filled with reproductions of some surprisingly beautiful (and occasionally surprisingly hilarious) covers, along with sidebars discussing specific artists and their biographies. How did the format come together with all the full-colour reproductions? Was there any trouble clearing rights for the art? Were you involved in the design?

Doogie Horner and Tim O’Donnell were the art directors on the book and they really did heroic work. Tim actually left the project in the middle because his mind finally snapped under the weight of all the haunted computers and robot minotaurs. He says he took a different job at another company, so whatever makes his family feel more comfortable. Doogie carried it across the finish line but it might have driven him mad in the process, too.

We all knew from the beginning that the covers would be crucial to the book, so when I wrote the manuscript I also mapped out which covers would go on which pages, which led to an insane-looking manuscript since that’s definitely not the norm. I tracked down every artist I could identify and got their permission to use their work, paying for it out of my own pocket if necessary, and a lot of them did interviews and were really generous with their time. But identifying them was tough. Publishers went out of their way to obscure artist signatures, either cropping them out or blurring them, or covering them with the title, so Will and I spent a lot of time magnifying hi-res scans to maximum resolution and scouring them to find signatures hidden in the artwork by the artists, identifying partial signatures, or finding initials and trying to attach them to the artist.

How did you establish the boundaries and structure of the book? You keep a strong focus on genre paperbacks, and on overlooked and forgotten writing. Was that always the primary idea? Similarly, the chapters are structured around subgenres, not chronologically; but the sense of the field and of developments over time comes through very clearly. Was the division by subject part of your plan from the start?

How did you establish the boundaries and structure of the book? You keep a strong focus on genre paperbacks, and on overlooked and forgotten writing. Was that always the primary idea? Similarly, the chapters are structured around subgenres, not chronologically; but the sense of the field and of developments over time comes through very clearly. Was the division by subject part of your plan from the start?

Finding the structure was the hardest thing, and that’s where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction became invaluable. I needed someone who knew the material to talk with and bounce ideas off of in order to find the right way to organize all this information. The idea that there was a horror paperback boom that started in 1967 with Rosemary’s Baby and ended around 1996 with the shuttering of Zebra’s horror line is not one that existed before this book. Will and I spent a long time talking, “Who was last? Where was Leisure in all this? Was The Rats the first animal horror book? Was the Kastel cover of Jaws enough to make it count as part of the paperback boom?” And slowly this storyline emerged.

I was wondering whether you saw the nature of the books as being shaped by their format? Do you think there was something about the nature of paperback publication that encouraged this kind of writing? As the mass-market paperback format passes away, is something being lost?

In the Seventies, at the big imprints like Bantam and Pocket there wasn’t anything cheap about paperbacks. It was the smaller imprints like Playboy Press, Holloway House, then Leisure, Pinnacle, and Zebra that made up what we think of as the pulpier publishers. They worked fast, went for the most eye-grabbing covers, and had to keep their margins tight. So they produced the glut of these pulpier novels and those are often the craziest, least-accomplished ones, although there are exceptions. These days, this kind of pulp production has moved to the self-publishing market to a large extent. Someone needs to chart those dark waters for me, because it’s an area I don’t know much about.

Did you find that the publishers or editors had specific tastes that shaped the genre, or were they hands-off, allowing writers to do what they wanted? What was their role in creating these books? Did they provide ideas?

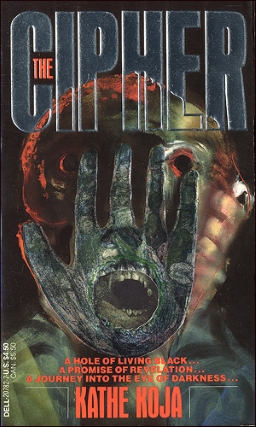

As far as I know, no editors provided ideas, but there were definitely editors whose tastes shaped their lines. Walter Zacharius and Rebecca Grossman’s “anything for a buck” tastes made Zebra home to scrappy, weird books. And Jeanne Cavellos specifically founded the Dell/Abyss imprint in the late Eighties as a reaction to the boom. She wanted to find authors who were more than Stephen King knock-offs, who wanted to write more than gorefests featuring women being raped and murdered. She sought out diverse, experimental voices like Kathe Koja, Michael Blumlein, and Poppy Z. Brite and while not all the Abyss books are classics, most of them are really exciting reads, even today.

As far as I know, no editors provided ideas, but there were definitely editors whose tastes shaped their lines. Walter Zacharius and Rebecca Grossman’s “anything for a buck” tastes made Zebra home to scrappy, weird books. And Jeanne Cavellos specifically founded the Dell/Abyss imprint in the late Eighties as a reaction to the boom. She wanted to find authors who were more than Stephen King knock-offs, who wanted to write more than gorefests featuring women being raped and murdered. She sought out diverse, experimental voices like Kathe Koja, Michael Blumlein, and Poppy Z. Brite and while not all the Abyss books are classics, most of them are really exciting reads, even today.

You have some lovely passages in Paperbacks From Hell discussing writers who impressed you, like Michael McDowell, Elizabeth Engstrom, and Ken Greenhall; and some great bits about writers whose work is especially ludicrous (in a good or bad way), like William W. Johnstone, Brian McNaughton, or Graham Masterton. I was wondering, though, if were there any writers that genuinely scared you, either deliberately in their writing, or in sense that they maybe weren’t quite right? Or to put it another way: what did you think was the most transgressive work you found?

Brenda Brown Canary’s Voice of the Clown is the only book to make my jaw drop on more than one occasion. I tried to locate her but couldn’t, and maybe that’s for the best. She only wrote one other book that I could find, a memoir of growing up in Oklahoma. But Voice is without a doubt thrilling and awesome and grotesque in all the best ways. It’s got some Native American woo-woo in it, but that’s easy to ignore. The story is about a little girl who doesn’t like the new family her dad marries into, and her clown doll whispers to her about how to drive all of them insane. Most people read the phrase “clown doll” and throw up.

Do you have a sense of the horror fiction field today? Has the serial-killer craze you describe as ending the golden age of horror paperbacks finally ended itself, and if so, what’s replaced it?

The field is coming back from the damage done by the bubble bursting in the mid-Nineties. For a long time, horror has been associated with gore and been branded as being cheap and tawdry. That’s changing now with writers like Laird Barron, Paul Tremblay, and Gillian Flynn, and they’re rebuilding the genre. Although these days with the thriller market so well-developed I think you have to look at it as part of this resurgence, too.

Beyond your own experience with the topic, how did you research the book, and what was it like? You mention some interviews in your acknowledgement section, and give a lot of credit to Will Errickson and his Too Much Horror Fiction blog (and have Errickson contribute an Afterword with some recommended reading suggestions). Were there any other sources of information you’d recommend?

Beyond your own experience with the topic, how did you research the book, and what was it like? You mention some interviews in your acknowledgement section, and give a lot of credit to Will Errickson and his Too Much Horror Fiction blog (and have Errickson contribute an Afterword with some recommended reading suggestions). Were there any other sources of information you’d recommend?

I did a lot of interviews, spent a lot of time talking with Will, and more than anything I read. There are a fair number of out-of-print books about the publishing business, and there are tons of old newspaper articles about the paperback industry written during the boom. I read everything from The Battle Creek Enquirer to papers in the proceedings of the Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States. I read author’s discontinued newsletters, and fanzines from the era. Anything and everything I could find got stuffed in my skull, and even if an entire run of newsletters only generated one new fact or one slight shift in perspective it was insanely valuable.

In terms of recommendations, Stephen King’s Danse Macabre is still one of the best histories of the genre ever published. And even though it’s out of print, Douglas E. Winter’s Faces of Fear: Encounters with the Creators of Modern Horror from 1985 is still worth seeking out. You can find copies for around $40 and the interviews in it give an invaluable insight into that era.

What, in the end, draws you to these books? You talk about the period feel of the books, and about the weirdness in so many of them — is there any distinctive quality to the weirdness that you don’t find anywhere else?

If you want something new, if you’re bored of what’s on offer, there is a huge ocean of these books waiting for you. I never understand why readers don’t dip into the recent past more often. These books don’t cling to current trends and ignore recent styles and feel more vivid because of that. They’re cheap, they’re easily available, and they’re great. I keep up with recent authors, but I’m far more excited about stumbling across a George V. Higgins I haven’t heard of, or an Ed McBain 87th Precinct mystery I’ve never read than reading whatever’s currently moving up and down the bestseller list.

Beyond Paperbacks From Hell, what other projects do you have out or coming out soon? I know the movie Mohawk which you co-wrote premiered at Fantasia, and I’ve seen copies of your novel My Best Friend’s Exorcism on local store shelves. What else are you working on these days, and what else should we be looking for?

I’m just wrapping up my next novel. It’s called We Sold Our Souls and it’s about a metal band from the Nineties that never made it and are now older, sadder, and dealing with the consequences of selling their souls for a fame that never happened. It’s a bummer!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Great interview. Thanks.

I just my copy of Hendrix’s book today. It’s a hefty little book on top quality gloss. Looking forward to reading it.

Thanks, James! Hope you enjoy the book!