Fantasia 2017, Day 11: Finding Forms (The H-Man, Bastard Swordsman, and Gintama)

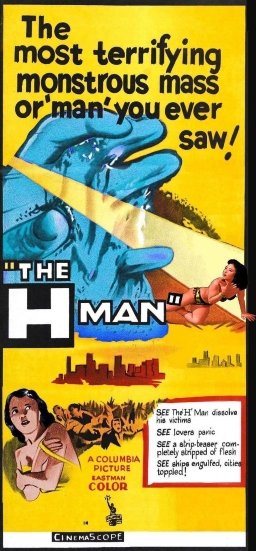

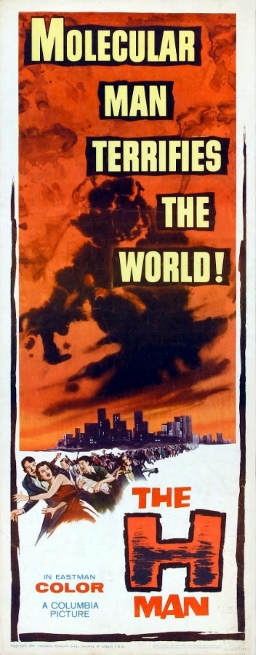

Sunday, July 23, I was down at Fantasia’s De Sève Theatre before noon to see a screening of the 1958 film The H-Man (Bijo To Ekatai-Ningen). I intended to follow that up with another vintage movie, the Shaw Brothers–produced 1983 film Bastard Swordsman (Tian can bian). Finally, I’d wrap up the day with a contemporary movie, the manga adaptation Gintama, which promised a mix of action and comedy. I liked the variety the films seemed to represent, and I was especially curious about The H-Man, which had been directed by Ishiro Honda, director of Godzilla.

Sunday, July 23, I was down at Fantasia’s De Sève Theatre before noon to see a screening of the 1958 film The H-Man (Bijo To Ekatai-Ningen). I intended to follow that up with another vintage movie, the Shaw Brothers–produced 1983 film Bastard Swordsman (Tian can bian). Finally, I’d wrap up the day with a contemporary movie, the manga adaptation Gintama, which promised a mix of action and comedy. I liked the variety the films seemed to represent, and I was especially curious about The H-Man, which had been directed by Ishiro Honda, director of Godzilla.

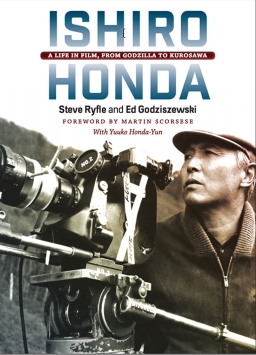

It was preceded by a talk about Honda’s life given by Ed Godziszewski, who had co-written (with Steve Ryfle) Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. The book comes out on October 3, with a foreword by Honda fan Martin Scorsese. It was clear that Godziszewski knew his stuff, though he had so much material he ran out of time before the film had to start. Nevertheless, what he had to say was fascinating. Without wanting to replicate Honda’s Wikipedia entry (which is relatively sparse, anyway), I want to mention some of the more interesting points Godziszewski raised.

Godziszewski began by recalling how his book came about, with the assistance of Honda’s family, and how he and Ryfle were able to see Honda’s entire body of work, including films never seen outside of Japan and rarely inside. Honda had done a lot of realist movies, especially in the 50s, that had been lost to the public for a long time and were only now beginning to show up again. Godziszewski talked about the experience of seeing 25 films he’d known nothing about, and how they demonstrated that Honda was a versatile, wide-ranging filmmaker.

Godziszewski talked about Honda’s life with a slideshow accompaniment. He started by noting that Honda was great friends with Akira Kurosawa, dating back to the 1930s; while Kurosawa’s films presented Japanese art cinema to the world, Honda’s work received the first international release of a non–art-house Japanese film. If Kurosawa was noted for being argumentative and dictatorial, Honda was reserved but friendly. Born in 1911 in a small town to a father who’d become a monk, Honda learned about the wider world from science magazines his brother sent to him from Tokyo. Honda only saw a train for the first time when, in the third grade, he moved with the rest of his family to Tokyo — where he was introduced to movies. Honda was fascinated by the medium, and retold the plots of the silent films he saw to his blind cousin (Japanese films of the time were in fact usually presented with a narrator).

At the time Honda went to college Nippon University opened a (initially somewhat disorganised) film study program. His studies there led to work with the Japanese film company PCL, starting as an assistant director — which meant that he worked at every task in filmmaking, from building props and costumes to developing film, as a way of learning his craft and getting to know the different jobs involved in a production. Honda, Kurosawa, and a third director named Senkichi Taniguchi (whose 1965 Key of Keys would be redubbed by Woody Allen as What’s Up, Tiger Lily?) became known as the ‘three crows,’ friends who worked together on each others’ films.

At the time Honda went to college Nippon University opened a (initially somewhat disorganised) film study program. His studies there led to work with the Japanese film company PCL, starting as an assistant director — which meant that he worked at every task in filmmaking, from building props and costumes to developing film, as a way of learning his craft and getting to know the different jobs involved in a production. Honda, Kurosawa, and a third director named Senkichi Taniguchi (whose 1965 Key of Keys would be redubbed by Woody Allen as What’s Up, Tiger Lily?) became known as the ‘three crows,’ friends who worked together on each others’ films.

In 1935 Honda was drafted, and found his career threatened by the 2-26 Incident, an attempted coup d’état by elements of the Japanese military. Honda had nothing to do with the coup himself, but his commanding officer did, and as a result everyone in the regiment was considered suspicious. Honda ended up being sent to the front in China; while he was able to return to the studio briefly, he was soon called up again, and was put in charge of “comfort women,” prisoners forced into sexual slavery. In Godziszewski’s telling, Honda became known for listening to and commiserating with the women and soldiers at his “comfort station.” He saw the misery caused by a war he considered pointless, and suffered a near-death experience on a battlefield. Although he’d eventually be called back to the front a third time, he never pointed a weapon at an enemy and couldn’t stand the idea of taking another life, even though he knew his anti-war sentiments put him in danger from the officers around him. Honda was eventually captured by the enemy and imprisoned as a POW. He survived, but his family would recall him waking up screaming in the middle of the night years later, suffering from dreams of the war.

Feeling as though time had passed him by due to his extended time in the military, Honda had to start his career over. He finally made a feature in 1951, The Blue Pearl (Aoi shinju). At about this time he married his wife, a script girl who held her own in drinking and talking movies with Honda and Kurosawa. Her family, who did not approve of Honda, disowned her; Godziszewski suggested this family conflict led to Honda frequently returning to the theme of the clash between tradition and individual desires. At any rate, Honda began making all kinds of movies — melodramas, musicals, gangster films, and many more. Passing now quickly over the success of Godzilla, Godziszewski noted that in 1979 Honda began working with Kurosawa as Assistant Director on films such as Kagemusha, Ran, Dreams, and Maadadayo. He was particularly useful to Kurosawa in directing military scenes, given his experience in the army.

Godziszewski then set up the movie we were about to see. Made in 1958, after Honda had been making comedies and what were called “women’s films,” the movie featured several actors that were part of a loose troupe who often starred in Honda’s films. It was released in the United States in 1959, as part of a three-picture deal with Columbia. The version we were about to see was a 35mm print with the 1959 dub.

Godziszewski then set up the movie we were about to see. Made in 1958, after Honda had been making comedies and what were called “women’s films,” the movie featured several actors that were part of a loose troupe who often starred in Honda’s films. It was released in the United States in 1959, as part of a three-picture deal with Columbia. The version we were about to see was a 35mm print with the 1959 dub.

Unfortunately, if traditional film can be astonishingly rich, it can also have real practical problems. That was the case with this print, I found. The colours had faded, and there was a certain amount of noise on the screen. More annoying was the fact that some scenes had been spliced into the wrong reel, meaning we got scenes out of order. Since we were watching a print of the American version, we were also getting a version that had been re-edited to provide plot points in a different order. And, of course, it was dubbed instead of being subtitled. I respect the fact that some dubs can be quite effective, but in this case for some reason the voice actors felt the need to adopt Japanese accents for their characters (one wonders if they thought the audience wouldn’t notice the film was set in Japan otherwise).

As for the story, it begins with footage of a nuclear explosion. We cut to Japan, where a gangster on a nighttime drug deal (Hisaya Ito) is apparently melted by some unknown force. This leads to a police investigation, which drags in a cabaret singer named Chikako Arai (Yumi Shirakawa). The police also take into custody a scientist named Masada (Kenji Sahara), who was trying to speak to Arai because he has a theory about the gangster’s death — he believes the man had been melted by radioactive rain. The police don’t believe him, but by this time the underworld’s trying to find the missing man too. And then Masada finds some men who have a strange tale of an encounter at sea with a deserted ship. Evidence begins to mount that the crew have become radioactive monsters. The authorities begin to make plans to deal with them, but the underworld’s still concerned with their drug trade. It all ends up with a massive conflagration and characters desperately chasing each other through the sewers.

There are some very nice moments in the film. The almost abstract patterns of light in the atomic bomb footage at the beginning; the spooky nighttime flashback sequence aboard ship; a car chase; the special effects of the citywide fire set at the end to destroy the monsters. All these things were entertaining and visually engaging. I’d say generally that Honda showed a good eye for composition as well.

But all the things that struck me were genre elements. And much of the film is dedicated to creating a sense of realism. Even the crime and police procedural aspects aren’t given any sense of romance or melodrama; they’re deliberately paced, even dry. Much of the first half of the movie is dedicated to cracking the mystery of what happened to the missing drug dealer when we in the audience already know. There’s minimal tension, and little sense of jeopardy.

Things do pick up as Masada’s theories become more broadly accepted. And the crime elements gain in interest as they seem almost to contrast with the general sense of panic when the authorities announce that radioactive monsters are infiltrating Tokyo. The car chase that comes toward the end of the movie works as a kind of contrapuntal plotting, contrasting the main plot with the gangsters-and-drug-deal storyline, and creating a sense of breadth.

But the final scenes in the sewers, again involving the gangsters, don’t really come off. The monsters we finally see have been offscreen for too long. The plans developed to deal with them are too efficient. In a very real sense, the danger to the main characters are only incidentally the H-Men, which tends to undercut the science-fictional aspect and indeed the whole sense of a monster movie. More broadly, the mix of realism and genre elements felt to me only sporadically successful.

But the final scenes in the sewers, again involving the gangsters, don’t really come off. The monsters we finally see have been offscreen for too long. The plans developed to deal with them are too efficient. In a very real sense, the danger to the main characters are only incidentally the H-Men, which tends to undercut the science-fictional aspect and indeed the whole sense of a monster movie. More broadly, the mix of realism and genre elements felt to me only sporadically successful.

In and of itself, the realist sense is interesting, though not dramatic. Worth noting is Godziszewski’s observation that Honda took care to present Chinese and Korean minor characters, and also to show his Japanese characters reacting to them in subtly derisive ways — when a cop mocks a Chinese suspect by tossing him a newspaper, it’s a Chinese-language paper. That’s the kind of subtle detail that helps construct character and setting. More generally, the set dressing and exterior photography create a fine sense of place, a setting in which real people live and go about their lives. And then are threatened by radioactive monsters; and this is the problem, the mix of the genre into the realist. To me the movie feels too real to easily accept invisible monsters melting people (and leaving their clothes behind).

It’s entirely possible that my lack of familiarity with Japanese film of the 50s plays a part here. I did find the pacing slow, for example. The science-fictional elements, in particular, were added slowly and cautiously, as though the movie didn’t want to scare off its audience with unexpected ideas. It’s sometimes difficult to remember how distant the 1950s are from the present day, and how many things that are now common currency in popular culture then had to be carefully established for an audience.

Still, I felt the crime elements never quite fit in with the overall story and theme. Even assuming the venality and violence of the criminals was meant to represent in miniature the dark side of human nature, the weakness that could produce the H-Men and (potentially) lead to their ultimate victory, it doesn’t feel as though it speaks to the H-Men in any specific way. You could use any of a number of examples of humans behaving badly, and I don’t know that you’d have any more or less coherent of a movie.

I think the film’s too good to dismiss out of hand, even in its dubbed form. It’s unconventional in its choice of monster, and in what it tries to do with structure. It looks nice, and has some nice character moments. But the different things it does, even when they work individually, don’t harmonise. And the slow development of the main threat tends to undermine any sense of momentum. I’m usually hesitant to say a movie would be better off with more direct genre thrills, but I wonder if that’s not the case here. It feels to me like something that fell between two stools, for all the skill involved.

Godziszewski came out after the film to answer questions. He confirmed that the car chase was in fact largely shot outside of the studio. He briefly discussed the dub actors, and when asked about the differences between the Japanese and American versions of the film, said that the opening sequence with the bomb imagery was created for the American release; the original Japanese film opened with the sequence on board ship. Asked about the music, he observed that it was the first film scored by Masaru Sato, who would go on to work for Kurosawa. Asked about a song Arai had during the movie, he said that the original was in English, and not sung by Shirakawa.

A question about why the creatures weren’t shown led to a discussion of the limits of special effects at the time. He also observed that the use of fire to destroy radiation seems to have been based on an idea that fire and liquid couldn’t co-exist. Asked whether US science-fiction films had an influence in Japan in the 1950s, he said yes — although The Blob, which this film in some ways resembles, was made just after. There was a question about plans for a sequel, which would have involved Honda’s 1960 film The Human Vapour (Gasu ningen dai 1 gô). A question about the effects at the lend led Godziszewski to note that it was all done with elaborate miniatures. Asked if the film was popular when it was released, Godziszewski said it wasn’t a top-10 film on the year; more likely about 15th. Asked about the use of bomb footage, Godziszewski said that Honda was opposed to using actual footage of the bomb, thinking it would cheapen the film and make it dated. He drew a connection between The H-Man and Godzilla, noting that both were inspired by the same real story, about a fishing boat that wandered in range of an atomic bomb test.

That ended the questions. The next film I saw was the next thing to play at the De Sève, Bastard Swordsman, directed by Chin-Ku Lu, who co-wrote the script with Kuo-yuen Chang based on a novel by Ying Wong. Fantasia’s Co-Director of Asian Programming King-Wei Chu introduced the Shaw Brothers production, saying that we would be seeing the last extant 35mm print of the movie. He told us this was a late-period Shaw Brothers movie, from a time where the studio was getting experimental in the face of competition from Golden Harvest, which had overtaken the Shaw Brothers as Hong Kong’s dominant martial-arts movie studio thanks in part to Golden Harvest’s young superstar Jackie Chan. The story of Bastard Swordsman was originally intended for a TV show, but Ying Wong took the script and rewrote it as a novel, which was then adapted as a film. A sequel was also made, and in fact we got to see the trailer for the second film before the first film screened.

That ended the questions. The next film I saw was the next thing to play at the De Sève, Bastard Swordsman, directed by Chin-Ku Lu, who co-wrote the script with Kuo-yuen Chang based on a novel by Ying Wong. Fantasia’s Co-Director of Asian Programming King-Wei Chu introduced the Shaw Brothers production, saying that we would be seeing the last extant 35mm print of the movie. He told us this was a late-period Shaw Brothers movie, from a time where the studio was getting experimental in the face of competition from Golden Harvest, which had overtaken the Shaw Brothers as Hong Kong’s dominant martial-arts movie studio thanks in part to Golden Harvest’s young superstar Jackie Chan. The story of Bastard Swordsman was originally intended for a TV show, but Ying Wong took the script and rewrote it as a novel, which was then adapted as a film. A sequel was also made, and in fact we got to see the trailer for the second film before the first film screened.

Bastard Swordsman features excellent and elaborate set-pieces, giving us all the kung-fu we could want to see, in single combat and in large-scale brawls. First and foremost, it delivers what it promises. There are heroic orphans, maniacal villains (complete with maniacal laughs), hidden masters, unlikely costumes, and a seemingly unattainable love interest. All these things are woven together with a practised melodrama, in story structure and indeed in cinematic form; there are more zooms in this film than in a whole season of The Flash.

The plot has to do with Yun Fei Yang (Norman Chu), the bastard of the title, a servant at the kung-fu school of the Wu Tang clan. He’s in love with a noble young woman of the clan, but bullied by everyone else at the school. Luckily, he’s being taught kung fu by a masked master. Unluckily, a longstanding rivalry with Wu Tang’s enemies is about to be renewed. The secrets of the silkworm style are at stake, as lies, betrayals, and double-crosses mount. In the end, the good guys win, and a sequel’s set up.

As late-period Shaw Brothers movies go, this one struck me as highly structured. I’d hesitate to say “conventional,” but compared to something like Chin-Ku Lu’s own Holy Flame of the Martial World, this feels a little more like something from the studio’s glory days. Odd plot twists and flashy special effects still play major roles here, though. And those things come fast; you barely have time to register what’s happening before the tale’s taken another turn. In that sense it’s a fine example of what used to be called a romance — an adventure story, in which something’s always happening.

It has the paraphernalia of a typical kung-fu movie — a secret technique, an ancient rivalry, a training sequence that functions as a power-up for a main character, and so forth. If you’re familiar with Shaw Brothers movies, you’ll recognise a number of the sets and actors. The power of the kung-fu here raises it into an out-and-out fantasy, but if the visual effects are more elaborate than usual, I don’t think the basics of the plot are much more elaborate than a lot of the Shaw films. This isn’t the weird fantasy of Demon of the Lute, for better or worse.

It has the paraphernalia of a typical kung-fu movie — a secret technique, an ancient rivalry, a training sequence that functions as a power-up for a main character, and so forth. If you’re familiar with Shaw Brothers movies, you’ll recognise a number of the sets and actors. The power of the kung-fu here raises it into an out-and-out fantasy, but if the visual effects are more elaborate than usual, I don’t think the basics of the plot are much more elaborate than a lot of the Shaw films. This isn’t the weird fantasy of Demon of the Lute, for better or worse.

Instead, I’d say this is a good sample of the Shaw Brothers style. You can see what worked — the skill of the performers, the craftsmanship of the direction, the intense focus on what pleases an audience. And you can see why it didn’t last, why it was losing ground to Golden Harvest. It’s consiously artificial, in its shooting style as well as its plot structures. And its characters are conventional to the point of being forgettable.

Which may just mean that it’s a kind of pop storytelling, like the pulps, like dime novels before the pulps or like super-hero comics after. It’s stylised adventure fiction that moves fast and uses action to tell a larger-than-life tale. A kind of spirit moves through all this stuff, a spirit that finds different forms in different eras, just for a little while; a spirit whose venue is whatever kind of storytelling’s cheapest. A spirit that gets in and tells tales, most forgettable and some hallucinatorily weird and a few genuinely good, and establishes its conventions and draws a fan base and then fades as time moves on. A new form comes along, the cycle begins again — but the old stuff still draws fans.

So it is with the Shaw Brothers’ movies. They still have fans, and there’s a reason for that. The name’s something to conjure with. The opening fanfare at the start of each of their movies is an announcement of what’s to come, like seeing “Stan Lee Presents” on the splash page of a comic book. Some of the late Shaw movies are desperate, trying to find a new form, a way to stay relevant; and there’s some of that here, enough that it’s notable and interesting, but mainly you’re seeing a good solid kung-fu story told by people who really know what they’re doing. For certain viewers, myself included, that’s good enough.

So it is with the Shaw Brothers’ movies. They still have fans, and there’s a reason for that. The name’s something to conjure with. The opening fanfare at the start of each of their movies is an announcement of what’s to come, like seeing “Stan Lee Presents” on the splash page of a comic book. Some of the late Shaw movies are desperate, trying to find a new form, a way to stay relevant; and there’s some of that here, enough that it’s notable and interesting, but mainly you’re seeing a good solid kung-fu story told by people who really know what they’re doing. For certain viewers, myself included, that’s good enough.

I closed the day out back at the Hall Theatre with the manga adaptation Gintama. I had no idea what to expect from the movie. I knew it was based on a story about an alternate-reality 19th-century Japan visited by aliens. Beyond that I wasn’t sure. Directed by Yuichi Fukuda, who has previously adapted the notorious (and, I am assured, at least in Fukuda’s telling, hilarious) Hentai Kamen, it has a script by Fukuda based off the original comic by Hideaki Sorachi. The screening began with an introduction to the crowd of some fans cosplaying as characters; and then a brief video hello from the director and cast. And then the movie started. And whatever I might have expected was blown out the back of my head.

Let me begin by noting that science-fiction is often about colonisation and imperialism, one way or another. You can pretty easily map a story about an extraterrestrial invasion onto history from this planet of a technologically-advanced power conquering another society or societies (see, for example, here). Bearing that in mind, given that this is a Japanese story about technologically-advanced aliens coming to Japan in the mid-19th century, you can immediately see parallels to actual Japanese history. I’m no expert on that history, but even so certain thematic parallels struck me as the story played out. Still, I say all this only to reinforce this point: while there are serious ideas that can be read into the movie, it’s also one of the most gleefully frenetic comedies I’ve seen in a long while, with gags ranging from the immature to the metafictional to the outright surreal, and almost all of them landing.

Let me begin by noting that science-fiction is often about colonisation and imperialism, one way or another. You can pretty easily map a story about an extraterrestrial invasion onto history from this planet of a technologically-advanced power conquering another society or societies (see, for example, here). Bearing that in mind, given that this is a Japanese story about technologically-advanced aliens coming to Japan in the mid-19th century, you can immediately see parallels to actual Japanese history. I’m no expert on that history, but even so certain thematic parallels struck me as the story played out. Still, I say all this only to reinforce this point: while there are serious ideas that can be read into the movie, it’s also one of the most gleefully frenetic comedies I’ve seen in a long while, with gags ranging from the immature to the metafictional to the outright surreal, and almost all of them landing.

Here’s how the movie opens, more or less: after a scene-setting infodump, we’re introduced to a samurai, Shinpachi Shimura (Masaki Suda, also at Fantasia this year in Death Note: Light Up the New World, and almost unrecognisable from his star turn in Princess Jellyfish), who like all samurai has been thrown out of work by the invading aliens (a kind of federation of races), and who now works in a restaurant where he struggles to master a cash register (because the aliens have brought modern technology to Japan). A group of alien patrons bully him, until they accidentally spill the parfait of another samurai, Gintoki (Shun Oguri). Gintoki beats up the aliens, then breaks into a cheesy theme song to a montage out of an 80s TV show, until other characters start berating him for the silliness of the song and we cut to a video-game–like version of three characters mocking each other, then we cut to those same characters — Gintoki, Shimura, and the girlish alien Kagura (Kanna Hashimoto, who was in the Assassination Classroom movies) — watching TV, until Kagura decides they have to go bug collecting to find a particularly valuable insect in the woods nearby, at which point they find everyone else who will be important to the film is also hunting the bug by one ludicrous means or another, and so we get a series of memorable character introductions until the bug shows up and everybody chases it until they meet another samurai, Kotaro Katsura (Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, The Top Secret: Murder in Mind, and Strayer’s Chronicle, among others) and his pet, a giant alien duck. At which point, more or less, the plot really kicks in.

To this point everything’s been moving at sugar-rush hyperspeed, and, as you can see, trying to explain it really can’t catch the spirit of the lunacy. Now, though, things begin to slow a bit as we get to the actual story. There’s a killer at work in Edo. Katsura’s trying to track him down. Inevitably Gintoki and the gang get involved. And find out there’s something much bigger than a single killer at work. Forces are trying to destabilise the culture that’s been built in Edo fusing alien and Japanese traditions, at whatever cost in human life it takes. Will they succeed?

To this point everything’s been moving at sugar-rush hyperspeed, and, as you can see, trying to explain it really can’t catch the spirit of the lunacy. Now, though, things begin to slow a bit as we get to the actual story. There’s a killer at work in Edo. Katsura’s trying to track him down. Inevitably Gintoki and the gang get involved. And find out there’s something much bigger than a single killer at work. Forces are trying to destabilise the culture that’s been built in Edo fusing alien and Japanese traditions, at whatever cost in human life it takes. Will they succeed?

This is a solid plot structure, and the story works as an action framework on which to hang all kinds of comedy. In that way it’s not entirely unlike Ghostbusters, say, with a coherent genre narrative, actual mysteries, and a legitimately threatening villain. The comedy here is more frequent, broader, and almost infinitely more likely to break the fourth wall — to the point where the fourth wall barely exists, and we look at more a sort of fourth French window — but because the plot’s simple and strong, the story overall feels coherent. The characters are always engaging, even when they’re making metafictional jokes.

The movie’s packed with manga jokes. Gintoki’s a faithful reader of Weekly Shonen Jump, and compares his movie’s plot to serials like Parasyte. He’s buddies with a mechanic (Tsuyoshi Muro) who is a mechanic for apparently all manga characters everywhere, and his shop’s filled with oddly familiar items. Generally, the movie does a good job of keeping these in-jokes as just that, in-jokes which people who recognise them will get while others can still follow the plot of the movie. That said, there is one joke that will reward knowledge of a certain early work of Hayao Miyazaki, to the point where the characters wonder if the gag’s entirely legal.

It all fits in, though, as the characters argue about their movie’s faithfulness to the manga, and whether Katsura’s alien duck pet (named Elizabeth) actually works in live action or whether it looks like a guy in a suit. The jokes work, much more often than not, and even when juvenile or tasteless it rarely feels mean-spirited. The delivery’s strong, the acting overall entertaining and charismatic. The pacing’s well-handled, slowing for occasional emotional moments, moving lightly through most of the comedy, and handling action scenes well. The climax, aboard a massive airship, does go on for a while, and though I personally thought it worked I can imagine others finding it a bit much.

It all fits in, though, as the characters argue about their movie’s faithfulness to the manga, and whether Katsura’s alien duck pet (named Elizabeth) actually works in live action or whether it looks like a guy in a suit. The jokes work, much more often than not, and even when juvenile or tasteless it rarely feels mean-spirited. The delivery’s strong, the acting overall entertaining and charismatic. The pacing’s well-handled, slowing for occasional emotional moments, moving lightly through most of the comedy, and handling action scenes well. The climax, aboard a massive airship, does go on for a while, and though I personally thought it worked I can imagine others finding it a bit much.

But then part of the joy is that the whole film’s a bit much, and knows it. Characters fight partially for the cultural synthesis that’s been created after the alien invasion, and mainly to keep people from dying; that makes them sympathetic, even if the lead is “the dumbest samurai in the universe.” The movie’s smart enough to make up for it, filled with visual jokes and detail. It’s a fun ride, and when it was over all I could think was: yes, more like this, please.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.