Peplum Populist: Howard Hawks Goes to the Land of the Pharaohs (1955)

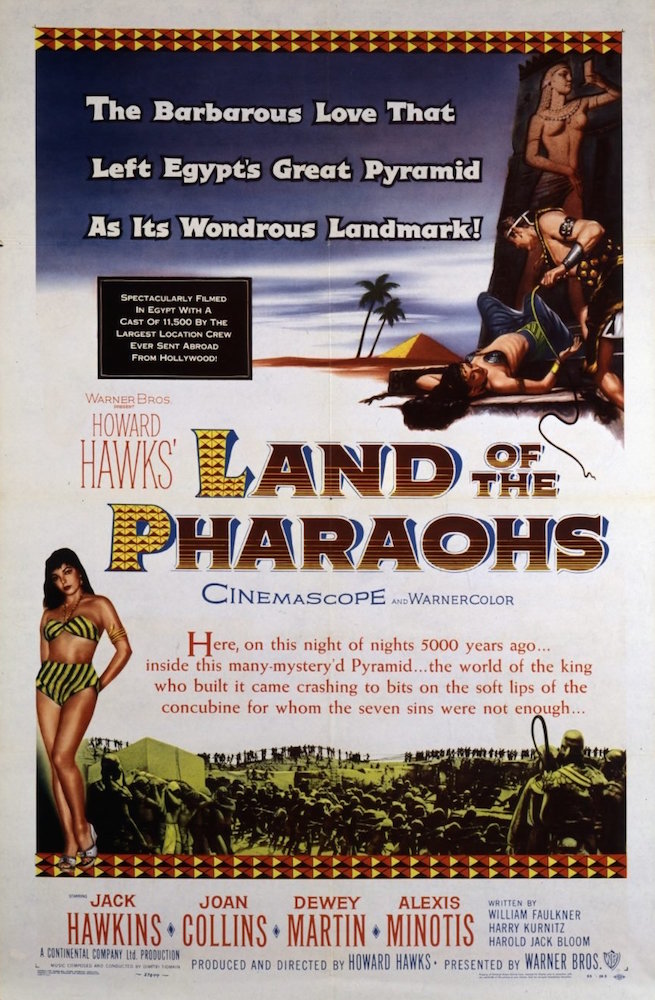

I didn’t think of putting Land of the Pharaohs under my “Peplum Populist” banner at first, even though peplum (sword-and-sandal) can be used as a broad description for any historical epic set in the ancient world. Ben-Hur is peplum. Quo Vadis is peplum. Spartacus is peplum. 300 is peplum. But for the purposes of this occasional feature, I was sticking to the specific historical definition, which is the Italian-made movies produced between 1958 and 1965. However, 1955’s Land of the Pharaohs is a genuine sword-and-sandal film, and there’s no rule except my own against expanding the umbrella of the genre to discuss a movie from one of the greatest of all Hollywood filmmakers — a movie that also happens to be his oddest foray outside of his usual style.

I didn’t think of putting Land of the Pharaohs under my “Peplum Populist” banner at first, even though peplum (sword-and-sandal) can be used as a broad description for any historical epic set in the ancient world. Ben-Hur is peplum. Quo Vadis is peplum. Spartacus is peplum. 300 is peplum. But for the purposes of this occasional feature, I was sticking to the specific historical definition, which is the Italian-made movies produced between 1958 and 1965. However, 1955’s Land of the Pharaohs is a genuine sword-and-sandal film, and there’s no rule except my own against expanding the umbrella of the genre to discuss a movie from one of the greatest of all Hollywood filmmakers — a movie that also happens to be his oddest foray outside of his usual style.

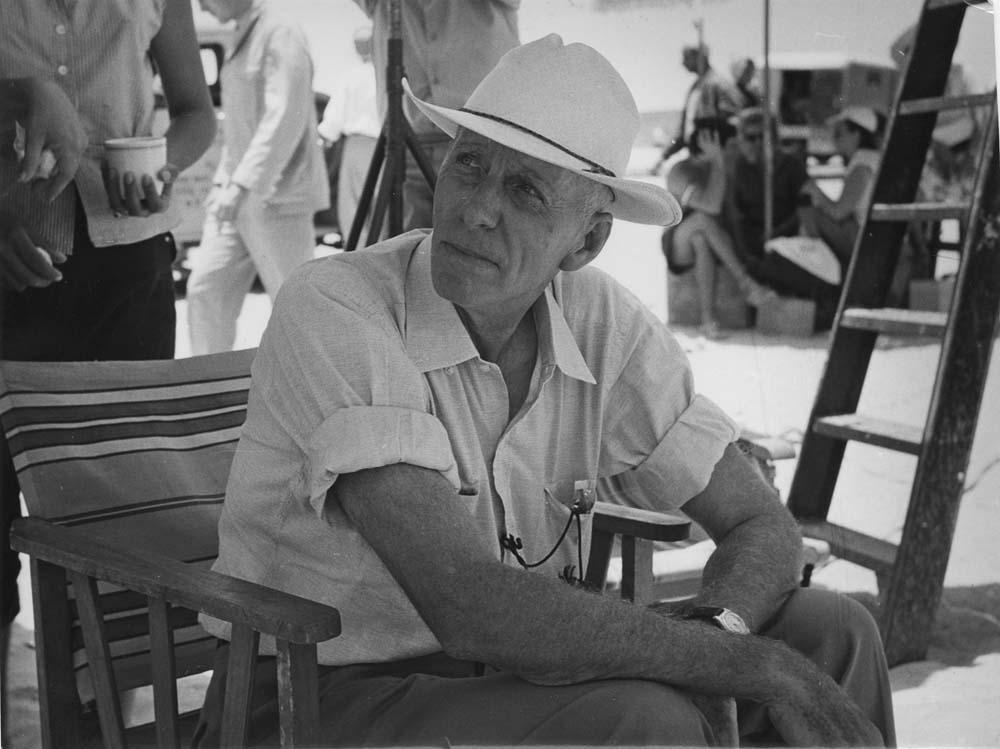

Howard Hawks is a name so colossal in the history of American movies that he feels like a stone monument of pharaonic Egypt, carved against a rock hill in the Valley of Kings. But Hawks only made one trip to ancient history and the historical epic with a film that has never achieved major recognition. Even with Hawks’s name on it and the continuing popularity of classic Hollywood ancient epics — especially with the technology of HD TVs making them look better at home than ever before — Land of the Pharaohs is little discussed. It’s never received anything more than standard-def DVD releases (one of which packaged it as a “Camp Classic,” which it definitely isn’t). The $3 million film was a box-office failure on its premiere, but this has never stopped a film from later gaining appreciation and a dedicated following. If it did, I wouldn’t be running a John Carpenter career retrospective series right now.

There has been some low-level buzz about Land of the Pharaohs. Martin Scorsese has called it his favorite movie as a child and a guilty pleasure as an adult. But this isn’t enough, so I’ll add a bit love (well, “like” would be a better word) for this unusual chapter in the career of a master filmmaker. It’s not essential Howard Hawks, but it’s Howard Hawks taking a whack at crafting a Cecil B. De Mille-style flick, and that’s worth something. Besides, I’m a sucker for this genre, and Land of the Pharaohs is a fascinating oddity among the ‘50s and ‘60s epics. Its strange, dispassionate approach makes it feels unlike anything else made at the time.

The Engineering Epic

Land of the Pharaohs asks that age-old question, “How can you most effectively build a magnificent tomb for yourself and arrange to have everyone involved in the process killed so no one knows its secrets?” This is the crux of the movie: the consuming quest of Pharaoh Khufu (Jack Hawkins), known to later Greek historians as Cheops, to build a looter-proof tomb during his lifetime and silence all involved in its construction. That the looter-proof tomb is the Great Pyramid of Giza is the movie’s selling point.

The script tells an almost entirely fictionalized account of Khufu’s reign, but it’s fictionalized out of necessity; records for the time of the Fourth Dynasty (the twenty-sixth century) are so scarce that historians are uncertain of the length of Khufu’s reign. Khufu rejects multiple plans his architects devise for an impregnable tomb. He instead turns to an ingenious slave, Vashtar (James Robertson Justice), to engineer a pyramid that can be fully sealed with a complex series of sand weights after the pharaoh is entombed. As payment for Vashtar’s services, Khufu will free his people. There’s a hitch, however: to guard the pyramid’s secrets, Vashtar must submit to his own execution when the task is completed. Vashtar agrees. His son, Senta (Dewey Martin), provides assistance, but his father hides this from Khufu so the pharaoh won’t also insist that Senta share his father’s fate.

Although I believe Hawks might have been happy to leave the movie with this plot and focus on the many years of engineering challenges and funding problems over the building of the pyramid, there had to be some royal melodrama and sex tossed in. This enters the story as Princess Nellifer (Joan Collins in one of her first major roles), a Cypriot ambassador who offers herself as tribute to Khufu and becomes his second wife. She’s a literal gold digger, having seen the treasure Khufu plans to bury with himself and greedy to ensure that it goes to her rather than get sealed in a tomb. Nellifer plots with her lover, the captain of the guard, to kill Khufu’s first wife, Queen Nailla (French single-name actress Kerima), her son, and then Khufu so they can gain control of Egypt. The assassination attempt on the queen and her son using a complex scheme involving a flute and a cobra (a well-done scene) ends up killing only the queen. Khufu digs into the matter, leading to a showdown with the captain of the guard and Nellifer. In the film’s admittedly spectacular climax, the giant trap Vashtar made out of the Great Pyramid ends up working far too well, trapping Nellifer along with Khufu’s mummified body. Vengeance through engineering!

Why did Land of the Pharaohs fail at a time when historical epics were a license to print money? And how did it become a financial misstep in the career of one of the most consistently successful directors of all time? Hawks had his own theory for why the movie flopped with audiences: “I should have had somebody in there that you were rooting for. Everybody was a son of a bitch.”

It’s not so much that everyone in Land of the Pharaohs is a horrible person. Vashtar and Senta are decent men trapped in an obligation to construct Khufu’s pyramid to liberate their people, and Queen Nailla is pleasant if passive. It’s that even the sympathetic characters are imbued with coldness and distance. The protagonist is where the serious problem lies. Khufu is the character we spend the most time with, as the main story is his quest to construct the ultimate resting place for himself and how his scheming second wife undoes his household. But Khufu is an inflexible, unlikable chap. His focus on the afterlife and refusal to understand that many of his requests are unreasonable make it hard for audiences to get behind him. Khufu spends a great deal of time arranging to have all the people associated with building the interior of his tomb executed upon his own death. Most viewers will have a hard time sympathizing, even though it’s the actual tradition of the Old Kingdom.

Joan Collins as Princess Nellifer is the standout of the cast, and not only because so much visual glamor is poured on her. Nellifer’s motivations are accessible to a modern audience, and what she wants is corporeal. Collins delivers the performance that comes closest to a modern, even somewhat Hawksian, character. A good villain is welcome in a melodrama that’s dry elsewhere. (It’s unfortunate the publicity department went too modern with Collins on the posters, placing her in a ludicrous contemporary bikini. No, she doesn’t wear anything like that in the film.)

Star Jack Hawkins put some of the blame for the film’s failure on the difficulty of the dialogue. The experienced actor felt many of the lines were difficult to speak. Hawks agreed: “It was a great idea but [screenwriters William] Faulkner, Harry Kurnitz, Harold Jack Bloom and myself could never figure out how an Egyptian should talk.” I think they pulled it off as well as possible, since the characters don’t sound remotely like modern people and the often fatalistic attitudes create an illusion of the Bronze Age within a Hollywood melodrama. But it doesn’t make for a lively Howard Hawks film, unfortunately. Howard Hawks was a far, far, (far100) superior filmmaker to Cecil B. DeMille, but this type of stiff epic was something DeMille was more comfortable with.

Hawks couldn’t deliver a completely bad film, but Land of the Pharaohs isn’t in the snappy character-driven territory where he excelled, and you can sense his discomfort working with scenes containing thousands of extras staged purely for pomp. Take a look at one of Hawks’s masterpieces, Only Angels Have Wings (John Carpenter’s second favorite movie, by the way), a thrilling tale about aviators flying across South American mountains that almost never leaves the single location of a bar. Hawks was superb at putting characters ahead of standard plotting, placing exciting people — contemporary people (even when in the Old West) — in lively situations.

Although Hawks wasn’t fond of the widescreen CinemaScope process, it’s not something apparent; visually, Land of the Pharaohs looks fantastic. This is probably the part of the movie Martin Scorsese fell in love with of, since he came of age when CinemaScope and VistaVision were electrifying moviegoers with new sights, and he found the technical challenges and potential of the formats thrilling.

Although Hawks wasn’t fond of the widescreen CinemaScope process, it’s not something apparent; visually, Land of the Pharaohs looks fantastic. This is probably the part of the movie Martin Scorsese fell in love with of, since he came of age when CinemaScope and VistaVision were electrifying moviegoers with new sights, and he found the technical challenges and potential of the formats thrilling.

Land of the Pharaohs boasts a major advantage over many of its epic siblings: brevity. Where Ben-Hur consumes three hours and forty-four minutes of screentime and DeMille’s Ten Commandments clocks in at only four minutes shorter, Hawks brings in his epic at a brisk 106 minutes. He spent far longer telling the tale of a cattle drive in Red River and a few men guarding a jail cell in Rio Bravo than constructing one of the Wonders of the World. Hawks understood how much time a particular story required to tell, and didn’t push over it just because he could. Land of the Pharaohs is the exact length it needs to be. It doesn’t have the character complexity of Red River or Rio Bravo, only ancient spectacle, simple court intrigue, and engineering issues. No need to belabor it.

Whatever the cause of the initial failure of Land of the Pharaohs, it forced Hawks to take a break from filmmaking for a few years. When he came back, it was for Rio Bravo with a script by Leigh Brackett. Nice recovery, Howard.

Whither a Blu-ray?

Land of the Pharaohs is ideal for Blu-ray treatment. It’s a visually rich movie shot during the early explosion of widescreen formats, and these are the older films that excel in a Blu-ray presentation. You only have to watch the Blu-ray of the first CinemaScope movie, 1953’s The Robe (another seminal film for young Mr. Scorsese), to see the spectacular way the process pops on 1080p. However, the film is currently only available on DVD-R from Warner Archive, the manufacture-on-demand division of Warner Home Video.

I learned an important lesson from the Valley of Gwangi Blu-ray release: just because Warner Archive puts a catalog title out on a DVD-R doesn’t mean they’ve slammed down the gate on the possibility of doing a Blu-ray in the future. So today I’m making this request to the good folks at Warner Archive, which is to give Land of the Pharaohs a Blu-ray. It’s already on MOD DVD, but if that didn’t stop them with The Valley of Gwangi, why should it stop them with a Howard Hawks movie? Even if it was a financial failure — but then, so was Gwangi.

In closing … oh, great gods of Warner Archive, as you ride across the dome of the sky, please consider this servant’s humble plea for a Hi-Def disc of Land of the Pharaohs. Although if you want to get to Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid first, that’d be great too.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

I watched this movie not too long ago and found it a reasonable amount of fun. The only thing holding it back, I think, was the inescapable feeling that Hawks was slightly embarrassed by the whole thing. The obvious comparison is with the historical/biblical films of Cecil B. DeMIlle, and my Land of the Pharaohs disc has a commentary by Peter Bogdanovich in which Bogdanovich is at great pains to explain why a great director like Hawks could deliver a film that wasn’t nearly as entertaining as the epics made by DeMille. Bogdanovich wound up pretty much saying that Hawks’ movie comes off worse in comparison BECAUSE he’s so much the better director…which seemed to me an odd argument. Sampson and Delilah and the Ten Commandments are do deliriously entertaining because DeMille was sophisticated enough to know that with this material sophistication wasn’t what was called for – shamelessness was.

If they were having so much script difficulty, I wonder why Hawks didn’t just bring in Leigh Brackett? He worked with her before, he worked with her after, and her Martian stories had a sense of the historical epic about them. Maybe if she had been brought in it would have been a better movie with better dialogue.

Those names make my inner ancient history nerd weep. WEEP!