Operation Arcana, edited by John Joseph Adams

Operation Arcana

Operation Arcana

Edited by John Joseph Adams

Baen(320 pages, $15 trade/$7.99 paperback/$6.99 digital, March 3, 2015)

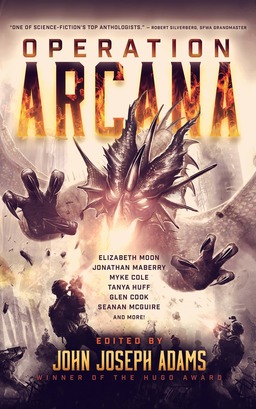

Cover by Dominic Harman

Operation Arcana is another collection by prolific editor John Joseph Adams, built of stories crafted around a theme that gives it a fairly unique flavor among recent speculative fiction anthologies. That theme is basically something like “soldiers and magic.”

On first blush, especially considering the cover image of modern soldiers using assault rifles against a rearing dragon, that might seem a bit of a cheesy juxtaposition. But it actually works quite well, and Adams has crafted an anthology of consistently compelling stories. There’s a wide spectrum of tales here, from alternate histories in which historical wars are fought with magical aid, to realistic slipstream in which modern soldiers encounter mythical creatures, to high fantasy focused on the gritty lives of campaigners.

More than just compelling stories though, there’s something about the juxtaposition of magic and warfare that seems to just really work. Why? I think the authors have stumbled onto something profound in their disparate tales, and I think it involves this fact: that magic is defined by rules. Even if the rules are strange or mysterious, stories involving magic are almost always faithful to the orderly structure of the magic that undergirds their imaginary universes. By contrast warfare — or at least battle — in the real world is inherently chaotic. At times the violence appears meaningless and the carnage random. So there’s something very appealing and attractive about stories that play with this sense of chaos on a backdrop of rule-structured magical systems.

This tension is apparent in every story in the collection. Consider, for example, “The Graphology of Hemorrhage” by Yoon Ha Lee, which outlines a system of magic in which soldier-magician-scribes of an empire use calligraphy as a form of spell-casting to wipe out entire rebelling cities. Here, the emphasis is on the magical structure itself, so much so that when the narrator is erased as a byproduct of her magic, the author erases her from the typography of the story itself. Another prime example is “The Way Home,” by Linda Nagata, in which a band of American soldiers find themselves trapped in a pocket dimension and must quickly learn the magical rules that will allow them to find their way back out.

Of course, there are rules in warfare as well as in magic, but in war the rules are more tenuous, imposed and maintained by the soldiers themselves. “Mercenary’s Honor,” by Elizabeth Moon, has no explicit magic but rather addresses this aspect, examining the unwritten rules governing warfare between mercenary bands of gentlemen soldiers in a landscape resembling medieval Italy. Here, the role of the soldier is implicit in the structure of rules by which the soldier abides. This is even more so in “American Golem,” by Weston Ochse, in which a golem is created and programmed to enact revenge for a Jewish soldier slain in Afghanistan. Despite the specific rules that (magically) govern his behavior and which bring him into conflict with the rules and programming of actual flesh-and-blood American soldiers, the golem turns out to be more human than they. This idea of the rules implicit in being a soldier are taken to the limit in “The Damned One Hundred,” by Jonathan Maberry, in which a band of beleaguered defenders makes the ultimate sacrifice and participates in a system of black rules and magic in order to save their homeland from overwhelming hordes.

The stories in this collection range all over the fantasy spectrum, but they carry a surprising weight. I think at least part of this comes from the tension between the order of magic and the chaos of conflict and is perhaps most explicit in “Pathfinder,” by T. C. McCarthy, in which a nurse not only attempts to hold together some semblance of order in a Communist Korean army hospital being bombed by Americans but also to practice her traditional system of magically leading the souls of the dying to peace in the afterlife. In McCarthy’s tale, this orderly system stands for a traditional way of life being threatened not only by the chaos of war but also by a malevolent spiritual predator. Genevieve Valentine’s “Blood, Ash, Braids” lives in this tension as well, as a witch in a squadron of female Russian fighter pilots lays spells of binding on her colleagues’ canvas biplanes before battle. Again, the order of traditional magic is painted in sharp contrast to the chaos and uncertainty of early aerial combat.

Operation Arcana might get overlooked on a bookshelf alongside various Year’s Best anthologies, especially in its pocket-size Baen paperback format, but the collection was excellent — there was not a single poor tale in the bunch. Each one took the central theme of magic and warfare and did something compelling and gripping with it. “Bomber’s Moon,” by Simon R. Green, for instance, took this concept of magical rules of engagement perhaps furthest, translating it into a reinterpretation of the bombing of Dresden during World War II in which the fact that the Nazis have enlisted demonic assistance means the forces of heaven have come to the aid of the Allied bombers. Yet there are still strict rules: things the humans have to do for themselves, limits to celestial intervention. Or the haunting “In Skeleton Leaves,” by Seanan McGuire, a reinterpretation of Pan, Wendy, and Neverland in which the magical structure of the world itself is built on specific rules of warfare.

It seems somehow comforting — and as these stories show, also a fertile bed for good storytelling—to imagine an underlying order that the chaos of warfare cannot exceed without consequence. Yet the stories that feel strongest in the collection, that feel most realistic, undermine even the order of their underlying magical systems, showing magic as simply another weapon, one sometimes more chaotic and unpredictable than any other. “Bone Eaters,” by Glen Cook, is an excellent Black Company piece that does this by Cook’s usual disregard for orderly magic and his emphasis on life as a campaigner, but Myke Cole’s “Weapons in the Earth,” which I felt was the best piece in a great collection, does this even better. In this story, the unlikely hero is a goblin youth trying to cultivate his own connection with earth magic in the bitter, grim, and brutal reality of a prison camp. Twig, the goblin, finally finds his connection and (hopefully) a way to save his band, but only through despair and as a response to the brutality of war around him.

And that might be the kernel of all these stories: that magic offers a slender thread of hope — that the world works in a certain way, according to certain rules, even when some of the darkest episodes of human (or goblin) tragedy seem to overwhelm it. Of course, the rebuttal is that we actually do live in a world like that, except we call this order science and not magic. The thing about magic though, and part of its appeal in story, is that unlike science, magic sometimes comes when you call it.

Stephen Case has published fiction at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, and Daily Science Fiction. His reviews have appeared at Fiction Vortex and Strange Horizons, as well as his own blog, stephenreidcase.com. His last article for us was The Opportunity for Awe: An Interview with Scott Andrews.

This was an excellent anthology. My personal fav was “The Way Home,” by Linda Nagata.