Fantasia 2017, Day 10, Part 2: Inevitable Precisions (Born of Woman 2017 and A Day)

In 2016, the Fantasia International Film Festival created a showcase of short films by women directors: Born of Woman. It was a very real success, a collection of intriguing and often powerful films, and it travelled as a collection to several other festivals. 2017 saw a new iteration of the showcase, boasting nine shorts from seven countries. Born of Woman 2017 played Saturday, July 22, and I was eager to see what was in store this year. Afterward I planned to go on to see a feature film, a Korean thriller called A Day (Haru) built around the Groundhog Day–like device of a man repeatedly living the same day. First, though, would be Born of Woman.

In 2016, the Fantasia International Film Festival created a showcase of short films by women directors: Born of Woman. It was a very real success, a collection of intriguing and often powerful films, and it travelled as a collection to several other festivals. 2017 saw a new iteration of the showcase, boasting nine shorts from seven countries. Born of Woman 2017 played Saturday, July 22, and I was eager to see what was in store this year. Afterward I planned to go on to see a feature film, a Korean thriller called A Day (Haru) built around the Groundhog Day–like device of a man repeatedly living the same day. First, though, would be Born of Woman.

The program began with “A Little After Midnight,” (“Un peu après minuit,” also translated “Just After Midnight”) a 22-minute piece co-written and co-directed by France’s Anne Marie Puga and Jean-Raymond Garcia. It deals with a blind teacher (India Hair), witchcraft, and the interpretation of the world. If Hair’s teacher begins the film reliant on men’s sexualised tellings — a scholar who gives a fevered reading of one of Niklaus Mannuel Deutsch’s paintings of witches; later another man (Rémi Taffanel) who, at her request, tells her a pornographic story — then by the end of the story that’s changed as she finds a new source of power. There’s a subtext here, I think, deriving from Freud and his essay “The Uncanny,” in which he suggests the loss of the eyes is a symbolic castration. So in this movie there’s much to do with what is seen and what is hidden and the power that comes from seeing things — from identifying things and defining them. Visual art has resonance here, as do costumes that both hide and reveal. The film’s shot very nicely, with a dark, brooding feel that works well with the plot. The story’s not over-hurried, but the atmosphere’s the point, I think. If you can get into the feel of the thing, it’ll work; if not, perhaps not.

Next was Canadian Anabelle Berkani’s “Apocalypse Babies,” a dialogue-free five-minute piece starring her children, Evo and Zola Berkani. Sound clips from right-wing American radio mocking the idea of climate change frame a story about two children wandering a post-apocalyptic world, encountering scenes of death. It’s a solid enough vignette that brings home not so much the damage being done to the planet, but the blighted future being created by human willfulness.

Next was Canadian Anabelle Berkani’s “Apocalypse Babies,” a dialogue-free five-minute piece starring her children, Evo and Zola Berkani. Sound clips from right-wing American radio mocking the idea of climate change frame a story about two children wandering a post-apocalyptic world, encountering scenes of death. It’s a solid enough vignette that brings home not so much the damage being done to the planet, but the blighted future being created by human willfulness.

Next was “Waste,” a 16-minute film from American Justine Raczkiewicz, who co-wrote the script based on a short story by Amelia Gray. Roger (Luke Baines) works at a plant disposing medical waste, and lives with a new roommate, Olive (Sarah Bartholomew), who is obsessed with food — and has some unconventional tastes. It’s an engagingly off-kilter film, as we watch the two very different people try to communicate with each other and build some kind of relationship. There’s a subtle sense of wrongness that builds through the movie, an odd balance of shadow and brightness (both visually and in Bartholomew’s chipper performance). It comes to fruition in a memorably gory resolution, and yet maintains a real sweetness all the way through.

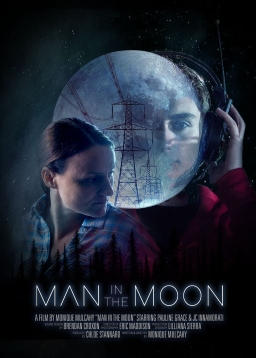

That was followed by Australian Monique Mulcahy’s 13-minute “Man in the Moon.” A huge moon is transmitting odd radio waves over a small town, where a single mother (Pauline Grace) is struggling to maintain her family and raise her teen son, Lincoln (JC Innamorati). Strange things build: the mother sees mysterious trespassers, but Lincoln’s increasingly absorbed by his games. It’s a horror-ish set-up, but ultimately feels like an 80s Spielberg movie seen from a different angle — from the perspective of a character on the outside, left behind. It’s well-made, with a good play of shadows and electric light, and it develops Grace’s character well; her fear and desperation and final longing hope come through.

That was followed by Australian Monique Mulcahy’s 13-minute “Man in the Moon.” A huge moon is transmitting odd radio waves over a small town, where a single mother (Pauline Grace) is struggling to maintain her family and raise her teen son, Lincoln (JC Innamorati). Strange things build: the mother sees mysterious trespassers, but Lincoln’s increasingly absorbed by his games. It’s a horror-ish set-up, but ultimately feels like an 80s Spielberg movie seen from a different angle — from the perspective of a character on the outside, left behind. It’s well-made, with a good play of shadows and electric light, and it develops Grace’s character well; her fear and desperation and final longing hope come through.

“The Last Light,” an American-Mexican film from directer Angelita Mendoza, written by Mendoza with Victor Capiz, was next. 11 minutes long, it presents the story of a missing girl in a small village, and her cousin (Izabella Limón) who finds a boy (Dante Montenegro Burgos) tied up in an abandoned building. It’s a story of a young person confronting too-human psychopathic evil. It’s a solid tale, told tersely through spare dialogue. The palpable danger surrounding the girl is nicely balanced by the determined but ultimately hopeless community that gathers around her cousin’s mother. Cross-cutting ratchets the tension up, even though the plot has an increasingly inescapable feel. It’s a bleak film about danger, and how even when a community rallies as one, it still may not be enough.

“Creswick,” a 10-minute Australian film, came next. Directed by Natalie James, and co-written by James with Christian White, it follows a woman, Sam (Dana Miltins) who’s helping her old father Colin (Chris Orchard) sell his house. That means she has to pack up all her childhood things; and it means she has to face her father’s deterioration in his old age. But is old age the only thing to blame for his problems? It’s a touching movie that’s also convincingly eerie. A simple set of props, discovered by Sam in Colin’s workshop, brings together both emotional strands: half-made chairs, each more distorted than the last. They could be a heartbreaking sign of the progress of Colin’s senility, or they could be disturbing non-Euclidean artifacts generated by something other than human. Or, conceivably, both. Either way, they’re unsettling, and the way they’re shot seems to encourage a polysemous reading: we see what Sam sees, and we can make of it what we want.

“Creswick,” a 10-minute Australian film, came next. Directed by Natalie James, and co-written by James with Christian White, it follows a woman, Sam (Dana Miltins) who’s helping her old father Colin (Chris Orchard) sell his house. That means she has to pack up all her childhood things; and it means she has to face her father’s deterioration in his old age. But is old age the only thing to blame for his problems? It’s a touching movie that’s also convincingly eerie. A simple set of props, discovered by Sam in Colin’s workshop, brings together both emotional strands: half-made chairs, each more distorted than the last. They could be a heartbreaking sign of the progress of Colin’s senility, or they could be disturbing non-Euclidean artifacts generated by something other than human. Or, conceivably, both. Either way, they’re unsettling, and the way they’re shot seems to encourage a polysemous reading: we see what Sam sees, and we can make of it what we want.

Next was the Spanish “Dead Horses,” written and directed by the team of Anna Solanas and Marc Riba. A 6-minute piece of stop-motion animation, it’s hard not to view it as “Guernica” come to life. In a bombed-out landscape, a boy and the remains of his family flee for their lives. It’s beautiful yet horrible, bleak yet rich; there’s an old-fashioned feel to the bombs and gas-masks we see, though the film doesn’t establish a specific setting. It’s a tone poem, with a simple story that ends at the right place for maximum impact. Even more than his sadness, the confusion of the child comes across, mixed terribly with the hopelessness we know to expect.

“REM,” from New Zealand, followed. Written, directed, and starring April Phillips, it tells the story of a security guard (Phillips) who finds a mad homeless man (Chris Ryan) who may be able to tell the future. It’s a 14-minute story, and solid enough; it’s a slow build, but paced well, so that you don’t entirely know which way it’ll develop. Once it does become clear what’s happening, and how Phillips’ character responds, then much of what follows is predictable. But getting there’s interesting enough, with a few startling dreamlike moments.

“REM,” from New Zealand, followed. Written, directed, and starring April Phillips, it tells the story of a security guard (Phillips) who finds a mad homeless man (Chris Ryan) who may be able to tell the future. It’s a 14-minute story, and solid enough; it’s a slow build, but paced well, so that you don’t entirely know which way it’ll develop. Once it does become clear what’s happening, and how Phillips’ character responds, then much of what follows is predictable. But getting there’s interesting enough, with a few startling dreamlike moments.

The showcase ended with Canada’s “Undress Me,” written and directed by Amelia Moses. It’s a horror film that feels much quicker than its 14-minute run time, about a woman (Lee Marshall) new to the university life who has a one-night stand a party, and finds herself living through disturbing consequences apparently as a result. It’s the rawest and most direct kind of body horror, and as such works fine. Marshall’s presentation of fear and disgust are gripping, as is the overall depiction of her character. In this movie, people affect others almost without noticing it, and there’s a sense that the horrific resolution is the revenge of the overlooked. The makeup effects are exceptionally well done, and overall it’s a convincing mixture of nastiness, gore, and despairing social awkwardness.

As a group, the showcase struck me as a display of thoroughly well-crafted films. The stories tended to avoid complex plot twists. Instead, on the whole, they tended to work by uniting two or more distinct emotions in one simple narrative. That’s a good approach, finding new angles on horror by bringing in other themes that in some way resonate with the horror elements. If there’s a similarity with last year’s films, it may be an overall sense of hardness, a rigor that’s not usual enough in genre.

As a group, the showcase struck me as a display of thoroughly well-crafted films. The stories tended to avoid complex plot twists. Instead, on the whole, they tended to work by uniting two or more distinct emotions in one simple narrative. That’s a good approach, finding new angles on horror by bringing in other themes that in some way resonate with the horror elements. If there’s a similarity with last year’s films, it may be an overall sense of hardness, a rigor that’s not usual enough in genre.

Several of the directors were on hand after the showcase to take questions. My notes, scrawled by hand, are probably even more unreliable than usual as I hurried to keep up with the replies. The directors were first asked why they told the stories they did. Annabelle Berkani of “Apocalypse Babies” said that she’d been listening to too much talk radio; she noted that she also had a French version of her film, using Québec-based radio hosts. Natalie James of “Creswick” said she wanted to tell a story about the shift in rules that come when you must begin to take care of your parents. Amelia Moses, director of “Undress Me,” said that she began with her final image of a person falling apart during sex and worked backwards. Angelita Mendoza, director of “The Last Light,” spoke about wanting to tell a dark story through the eyes of children. Jean-Raymond Garcia, who co-created “A Little After Midnight,” spoke about having a blind friend he wanted to help see (his collaborator Anne-Marie Puga said she came in late to the project). Finally, Monique Mulcahy of “Man in the Moon” said she wanted to take a coming-of-age story and turn it on its head; her film was inspired by the relationship of her brother and her mother.

They were then asked about the best and worst experiences they had while making their movies. Berkani said the best thing was finding the right shot; the worst was killing her son. James said that the best was getting her first assistant director into a morphsuit; the worst was the schedule. Moses said the best thing was seeing the make-up effects work after worrying about them; the worst was having only ten minutes to get her final shot. Mendoza said the best thing for her was finding locations for her film in Mexico; the worst things were the practical aspects of shooting on film. Garcia said the best thing for him was how everyone had energy and a plan to get their shots; Puga recalled last-minute production difficulties, finalising the script ten days before shooting, and having a school for the blind they hoped to work with pulling out at the last moment because they thought the story was “pornographic.” Mulcahy said the best things were rewriting, and repainting her location; the worst was a frantic recasting they had to do when their lead actor pulled out five days before shooting. (She also spoke about the lead actress as one of the best things, and wrangling extras as one of the worst.)

They were then asked about the best and worst experiences they had while making their movies. Berkani said the best thing was finding the right shot; the worst was killing her son. James said that the best was getting her first assistant director into a morphsuit; the worst was the schedule. Moses said the best thing was seeing the make-up effects work after worrying about them; the worst was having only ten minutes to get her final shot. Mendoza said the best thing for her was finding locations for her film in Mexico; the worst things were the practical aspects of shooting on film. Garcia said the best thing for him was how everyone had energy and a plan to get their shots; Puga recalled last-minute production difficulties, finalising the script ten days before shooting, and having a school for the blind they hoped to work with pulling out at the last moment because they thought the story was “pornographic.” Mulcahy said the best things were rewriting, and repainting her location; the worst was a frantic recasting they had to do when their lead actor pulled out five days before shooting. (She also spoke about the lead actress as one of the best things, and wrangling extras as one of the worst.)

Moses was asked about the practical effects in her film, and she said she’d always wanted to do a film that used practical effects heavily, as she was inspired by Cronenberg and 80s horror movies — which she described as looking good but not realistic. A friend of hers at Concordia does theatrical make-up, so she was able to get what she wanted. Asked if the ending she used was what had always been intended, she said yes. James was asked what her plans were for “Creswick,” and whether it had been made with the intention of expanding it into a feature. She said she wrote the script, was told it would work as a feature, then went back and rewrote it as a short with a different story in the same setting. She’s currently planning the feature. Asked about the chairs in the workshop, she noted that they visually echoed the human body. Berkani was asked where “Apocalypse Babies” was shot, and she said it was mostly shot in the Gaspé peninsula, with two shots in Montreal. Mulcahy was asked a question I didn’t catch about the visual effects in “Man in the Moon,” which she said were mainly involved with the moon and a portal at the end.

Festival director and programmer Mitch Davis was then asked if this collection of shorts would tour the way last year’s did. He said they were open to the idea, if people asked for it. They hadn’t intended to tour last year’s collection, but were asked by other festivals; their last show was in May, and though they intended to stop touring now that a new edition of Born of Woman had been put together, both the 2016 and 2017 editions were still available for booking. Asked how many submissions they’d had for this year’s program, Davis said it was in the range of 600 films; though he observed in most cases you could tell in about 9 shots whether you were in the hands of a storyteller or not.

Festival director and programmer Mitch Davis was then asked if this collection of shorts would tour the way last year’s did. He said they were open to the idea, if people asked for it. They hadn’t intended to tour last year’s collection, but were asked by other festivals; their last show was in May, and though they intended to stop touring now that a new edition of Born of Woman had been put together, both the 2016 and 2017 editions were still available for booking. Asked how many submissions they’d had for this year’s program, Davis said it was in the range of 600 films; though he observed in most cases you could tell in about 9 shots whether you were in the hands of a storyteller or not.

James and Mulcahy were asked about the strong sound design in their films; one of them observed that they’d gone to the same film school. James elaborated by observing that sound design was crucial to a film, and spoke about recording machinery to incorporate diagetic sound into the world of the movie. It took her two or three weeks to create a sound design she was happy with. Mulcahy agreed on the importance of sound, and spoke about meeting with her sound designer for her film. Moses was asked about inspirations for her movie, and she mentioned Cronenberg’s The Fly, but also Clueless; she wanted to evoke the feel of a college in the northeastern US. A question to the team behind “A Little After Midnight” led them to mention that their producer had wanted to do the film as a feature; they’d ended up cutting the script down.

Finally, the directors were asked what personal experiences affected their writing of their characters. Berkani, who had introduced her film before the screening by saying that she hadn’t expected Trump to become president and that was what her film was about, said that “I have kids and I’m really really worried.” James said that she’d been affected by having to cut her father’s toenails, and the whole experience of caring for him, while she also felt her writing reflected how her main character depended on her own father in childish ways. Moses said she was affected by social anxiety, and social expectations; this led to her making a film about following a socially-approved path and finding that social conformity isn’t good. Mendoza said her film in part came from obsessing over what was happening to her loved ones, and always imagining the worst case; she also wanted to incorporate Mexico as a place, and the way a community helps each other even when not related by blood. Puga said that she was fascinated by witchcraft, while Garcia spoke about having had four operations on his eyes, and his love of determined, heroic women. Mulcahy talked about the experience of hearing her mother tell her brother that his room was a pigsty, and generally the relationship of a mother and a son.

With the questions done, I headed across the street to the Hall Theatre to watch the debut feature by director Sun-ho Cho, A Day. Cho also wrote the tense time-loop film, which begins with a world-famous doctor, Jun-young (Myung-min Kim), returning home to Seoul to finally spend some time with his tween daughter (Eun-hyung Jo). Tragedy strikes, and she dies in a terrible accident just as he draws near their meeting-place. And then, as he weeps, he’s suddenly back on his plane, approaching Seoul. What follows is a first act like Groundhog Day or Edge of Tomorrow played as a nightmare thriller, as Jun-young tries again and again to reach his daughter before she dies, to warn her off, to in some way change what happens. Again and again, he fails. The future’s fixed — until suddenly it isn’t, as another factor suddenly suggests a whole other level to what’s happening to Jun-young.

With the questions done, I headed across the street to the Hall Theatre to watch the debut feature by director Sun-ho Cho, A Day. Cho also wrote the tense time-loop film, which begins with a world-famous doctor, Jun-young (Myung-min Kim), returning home to Seoul to finally spend some time with his tween daughter (Eun-hyung Jo). Tragedy strikes, and she dies in a terrible accident just as he draws near their meeting-place. And then, as he weeps, he’s suddenly back on his plane, approaching Seoul. What follows is a first act like Groundhog Day or Edge of Tomorrow played as a nightmare thriller, as Jun-young tries again and again to reach his daughter before she dies, to warn her off, to in some way change what happens. Again and again, he fails. The future’s fixed — until suddenly it isn’t, as another factor suddenly suggests a whole other level to what’s happening to Jun-young.

I’m being perhaps too careful in not giving away what that twist is. But I’d really rather keep as many of the secrets of this movie as I can. This particular twist is especially striking, a move that turns the whole Groundhog Day structure on its head. It comes at the end of the first act, and even knowing it was coming (I read it in the festival’s description of the film) it was a shock. It involves an ambulance technician named Min-chul (Yo-han Byeon), and it provides an exponential level of plot complication, deepening the mystery of what’s happening to Jun-young and his daughter. And it sets up further twists: is Jun-young struggling against fate? Or is there a deeper, more sinister, meaning to what keeps happening?

To say this is a tightly-structured movie is an understatement. The unexpected plot moves keep coming, and, crucially, both make sense and explore character. While we see a day repeat itself from a fixed beginning, over and over, it’s shaped by events from far before. The reason why it repeats, when it’s finally revealed, makes sense as dark fantasy — because it makes sense emotionally.

That is, in pure formal terms this isn’t a science-fiction movie. The explanation we get for what we see is essentially fantastic. But this isn’t really a fantasy in terms of how it plays out on screen. Given the logical way things develop, one could perhaps argue for the structure of the story as science-fiction. But to me it seems more like a horror story that isn’t interested in fear or a necessarily horrific ending. By that I mean that the plot’s built around twists that unsettle us, that make us reconsider everything we think we know. The end-of-Act-One plot twist I tried to avoid mentioning is an example of what I mean; we’ve seen enough of the movie to think we know what the story is, to guess what the rules are. And then somebody grabs Jun-young, and all the rules we’ve worked out without being aware we’ve worked them out shatter, and we’re left with the horripilating sensation of extreme dislocation. We’re not where we thought we were, not watching the movie we thought we were.

That is, in pure formal terms this isn’t a science-fiction movie. The explanation we get for what we see is essentially fantastic. But this isn’t really a fantasy in terms of how it plays out on screen. Given the logical way things develop, one could perhaps argue for the structure of the story as science-fiction. But to me it seems more like a horror story that isn’t interested in fear or a necessarily horrific ending. By that I mean that the plot’s built around twists that unsettle us, that make us reconsider everything we think we know. The end-of-Act-One plot twist I tried to avoid mentioning is an example of what I mean; we’ve seen enough of the movie to think we know what the story is, to guess what the rules are. And then somebody grabs Jun-young, and all the rules we’ve worked out without being aware we’ve worked them out shatter, and we’re left with the horripilating sensation of extreme dislocation. We’re not where we thought we were, not watching the movie we thought we were.

Characters that we’ve come to trust turn out to have done terrible things in the past. More importantly, again and again, the rules of the universe we think we’re coming to understand turn out not to be what we guess they are. What’s actually happening isn’t what we think. It’s a sleight-of-hand in plain sight, and new twists emerge from what we didn’t see like so many handkerchiefs and bunny rabbits.

Again, though, these twists allow the film to explore the characters in new ways. The actors here are solid with gusts to excellent, the stolidity of Kim’s Jun-young balancing the more fiery Min-chul of Yo-han Byeon. They’re given a lot of meat to wrestle with. Cho’s camera doesn’t concern itself with irrelevancies; the characters are front and centre, and the work of the actors is primary. Their choices, their work, are what I think of when I recall images from this movie. In a movie that repeats scenes, the ability of the actors to help tell the story is key — however subliminally, they keep reminding us where the different characters are emotionally and what they know or don’t know. The cast here help keep the narrative clear as it tidily advances and retreats in an unpredictable ebb and flow.

In a way, this is a film about family tragedies. There are deaths and betrayals, but every terrible action here is born out of love. There’s no infidelity, only grief and sometimes revenge. For all the terrible things that happen in the movie, there’s a sort of sweetness underlying its worldview. In this, again, it’s the opposite of a horror film. If the time-loop structure is inherently nightmarish — being stuck doing the same thing again and again, always facing an inevitable failure — the conclusion’s like the nightmare resolving into a dream. It’s less a eucatastrophe than a hard-fought resolution; character-based, it has no feel of an unexpected uplift. Instead it’s a missing piece clicking into place, a dream working itself out.

In a way, this is a film about family tragedies. There are deaths and betrayals, but every terrible action here is born out of love. There’s no infidelity, only grief and sometimes revenge. For all the terrible things that happen in the movie, there’s a sort of sweetness underlying its worldview. In this, again, it’s the opposite of a horror film. If the time-loop structure is inherently nightmarish — being stuck doing the same thing again and again, always facing an inevitable failure — the conclusion’s like the nightmare resolving into a dream. It’s less a eucatastrophe than a hard-fought resolution; character-based, it has no feel of an unexpected uplift. Instead it’s a missing piece clicking into place, a dream working itself out.

One can also argue this is a film about forgiveness. If sins of the past inevitably come out, the whole point of the story is that you can’t move on until they’re dealt with. And the only real way of dealing with them is forgiving them. If time repeats itself endlessly until the wrongs are accepted, atoned for, and forgiven, then the only question is how long it’ll take the characters to work out what must be done and summon the maturity to do it. Watching the process by which that happens is suprisingly moving, and I think would be even if all the twists were known. This strikes me as a re-watchable movie, not just for the sake of watching chess pieces sliding into their inevitable logical positions, but for the sake of watching the emotional journeys of the characters.

With the movie over, director Sun-ho Cho came out to take questions. The first was simple: where did the idea for the film come from? He said that the time-loop genre had become familiar, and as a director he wanted to make such a film, wondering how people would live life if it repeated day after day. But then he also wanted to add some differences to the pattern, like seeing one’s loved ones killed and racing against time to save them; while also having a character with mirroring goals. Asked about the main characters and their relation to fatherhood, Cho talked about wanting to tell a story about characters who were left after others died, and how that led him to fathers, to dramatise a particular kind of emptiness.

With the movie over, director Sun-ho Cho came out to take questions. The first was simple: where did the idea for the film come from? He said that the time-loop genre had become familiar, and as a director he wanted to make such a film, wondering how people would live life if it repeated day after day. But then he also wanted to add some differences to the pattern, like seeing one’s loved ones killed and racing against time to save them; while also having a character with mirroring goals. Asked about the main characters and their relation to fatherhood, Cho talked about wanting to tell a story about characters who were left after others died, and how that led him to fathers, to dramatise a particular kind of emptiness.

Asked how many of the scenes were reshot for the time loop, Cho mentioned two scenes. Asked what the greatest obstacle was in making the film, he said writing the scenario was the hard part. It had to be logical, making for dry work. He felt the casting was good, but the shooting was difficult, as they were shooting similar scenes in the same place that would take place at different points in the movie and which therefore meant the characters were in different states. In particular, every iteration of the accident to which the characters return was shot in one day. The order of scenes they were shooting ran the risk of becoming confusing.

A questioner in the audience pointed out that by the end of the film one character seemed ready to face responsibility for his past actions, while another did not; was this deliberate, or something that happened in editing the film? Cho agreed with the questioner’s reading of the film, but felt that there was regret shown in a decision regarding a name. Asked what was the greatest lesson he learned from making the film, Cho said it was to never forget what story he was telling and what he was getting across to the audience — that the film and story was a way to communicate with the audience. Finally, asked if he’d ever considered another ending, he said that while it was never considered as an ending, at one point in developing the scenario he considered an option in which one of the characters died, only to have another character find their day repeating in turn.

A questioner in the audience pointed out that by the end of the film one character seemed ready to face responsibility for his past actions, while another did not; was this deliberate, or something that happened in editing the film? Cho agreed with the questioner’s reading of the film, but felt that there was regret shown in a decision regarding a name. Asked what was the greatest lesson he learned from making the film, Cho said it was to never forget what story he was telling and what he was getting across to the audience — that the film and story was a way to communicate with the audience. Finally, asked if he’d ever considered another ending, he said that while it was never considered as an ending, at one point in developing the scenario he considered an option in which one of the characters died, only to have another character find their day repeating in turn.

That ended the questions, and ended also my own day at Fantasia. I’d seen two features, nine shorts, and a VR documentary; a good and varied day. The next would bring three more movies. Oddly, I didn’t feel like the characters in A Day, repeating the same experience again and again. I was getting up each morning, going to see movies, and going home — but the range of films, the variety of stories, meant every day was different. Each day I was getting different lessons in storytelling, watching narrative be stretched and structured in unpredictable ways. So it went, ever on: and the next day would show me three even stranger things.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.