Fantasia 2017, Day 10, Part 1: Welcome to the Future (Napping Princess and Welcome to Wacken)

On Saturday, June 22, I reached Fantasia’s Hall Theatre before noon to see a screening of the anime Napping Princess (Hirune Hime: Shiranai Watashi no Monogatari), a story about dreams, technology, and the 2020 Olympics. After that, I had a short film showcase to see, then another feature. But before either of those, I planned to pass by the Fantasia Samsung VR 360D Experience, which, as the name implies, gives people the chance to experience VR by watching one of a selection of short films. I’d tried out the technology last year with a number of short fiction films; this time out there was something a little different, a half-hour documentary called Welcome to Wacken, about the legendary annual German metal festival. I wanted to see how the technology would handle the documentary form, especially since I had all the respect in the world for the filmmakers — it was directed by Sam Dunn, whose previous work included the seminal metal documentaries Headbanger’s Journey and Global Metal.

On Saturday, June 22, I reached Fantasia’s Hall Theatre before noon to see a screening of the anime Napping Princess (Hirune Hime: Shiranai Watashi no Monogatari), a story about dreams, technology, and the 2020 Olympics. After that, I had a short film showcase to see, then another feature. But before either of those, I planned to pass by the Fantasia Samsung VR 360D Experience, which, as the name implies, gives people the chance to experience VR by watching one of a selection of short films. I’d tried out the technology last year with a number of short fiction films; this time out there was something a little different, a half-hour documentary called Welcome to Wacken, about the legendary annual German metal festival. I wanted to see how the technology would handle the documentary form, especially since I had all the respect in the world for the filmmakers — it was directed by Sam Dunn, whose previous work included the seminal metal documentaries Headbanger’s Journey and Global Metal.

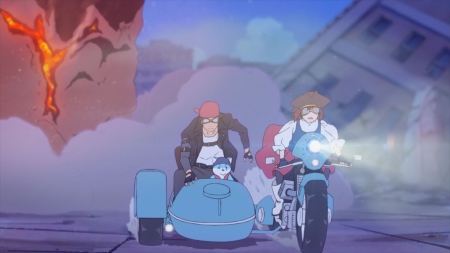

First, though, was Napping Princess (which, according to Wikipedia, is also known as Ancien and the Magic Tablet). Written and directed by Kenji Kamiyama, it begins in a dieselpunk otherworld called Heartland, where a daring princess named Ancien (voice of Mitsuki Takahara) seeks to regain her magic tablet with the help of an animated toy bear called Joy (Rie Kugimiya). A monster called the Colossus threatens Heartland, and Ancien’s father, whose palace is an enormous car factory like something out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, has ordered her confined to a tower. But she escapes, meets a rebellious motorcycle-riding mechanic named Peach (Yôsuke Eguchi), and joins with him to counter the mysterious plot of the king’s sinister adviser (Arata Furuta) and the giant Colossus that emerges from the sea.

Until Ancien wakes up. In the world we view as real, a Japanese schoolgirl named Kokone is dreaming Ancien’s adventures. It’s 2020, and the Olympics are about to take place in Tokyo; Kokone and her father, Momotaro, a mechanic in the southern town of Okayama, wonder whether the autonomous cars Japan’s promised as a major part of the opening ceremonies will be ready on time (note that Okayama’s the setting for the original legend of Momotaro). But then Momotaro’s arrested and accused of corporate espionage against Shijima Motors, the company building the autonomous vehicles. Kokone has to escape Shijima’s representative, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the evil adviser of the king of Heartland, and work out the secrets contained in her father’s old tablet computer. What secret in his background has emerged? And how does it connect to the story of Heartland?

Very cleverly, that’s how. The movie deftly mixes the two strands, handling pacing well not only within the sequences in either world but in the way the two worlds balance. Kokone’s naps take place at natural points in the story, while at the same time Napping Princess doesn’t hesitate to skip forward in the Heartland narrative as needed. This tends to insist on the primacy of the 2020 reality, while also keying in on big moments in the dieselpunk story. As the film moves along, the way the two stories are linked is complicated in some interesting ways — a notable twist is the discovery that Ancien isn’t necessarily the direct analogue for Kokone that she seems, and generally the dream-world of Heartland doesn’t just consist of one-to-one correspondences for people and things of Kokone’s 2020. The 2020 story’s filled with symbols, as stories tend to be, images that recur with some weight of meaning or emotional charge that can’t be precisely defined, and Heartland becomes a venue for exploring those symbols in a different way. Sure, a tablet computer filled with secrets in this world is Ancien’s magic tablet in the other; but more broadly, there’s a reason why the dream-world’s called Heartland, why Momotaro wears a jacket with a winged heart, why the film tells us directly: “With hearts united, we can fly.”

Very cleverly, that’s how. The movie deftly mixes the two strands, handling pacing well not only within the sequences in either world but in the way the two worlds balance. Kokone’s naps take place at natural points in the story, while at the same time Napping Princess doesn’t hesitate to skip forward in the Heartland narrative as needed. This tends to insist on the primacy of the 2020 reality, while also keying in on big moments in the dieselpunk story. As the film moves along, the way the two stories are linked is complicated in some interesting ways — a notable twist is the discovery that Ancien isn’t necessarily the direct analogue for Kokone that she seems, and generally the dream-world of Heartland doesn’t just consist of one-to-one correspondences for people and things of Kokone’s 2020. The 2020 story’s filled with symbols, as stories tend to be, images that recur with some weight of meaning or emotional charge that can’t be precisely defined, and Heartland becomes a venue for exploring those symbols in a different way. Sure, a tablet computer filled with secrets in this world is Ancien’s magic tablet in the other; but more broadly, there’s a reason why the dream-world’s called Heartland, why Momotaro wears a jacket with a winged heart, why the film tells us directly: “With hearts united, we can fly.”

If that sounds like a simple moral, the film manages to make it work as a mission statement. There’s a very strong fairy-tale sense here, obviously in the Heartland sequences, but increasingly in the 2020 scenes as well. Near-future technology comes to have the feel and even structural significance of magic: VR that can tell secrets, a mysterious correspondent on the other end of a text-message conversation, an autonomous vehicle that can whisk you away to another city while you sleep. By the end this is perhaps stretched a bit too far, as at least on first viewing certain actions taken at the climax by one of the machines feels unlikely. But it’s clearly meant to be pushing probability; there’s a justification for what’s happening, and the tone is one of eucatastrophe — technology here providing the unexpected good news that turns the story to a happy ending.

This is a story that is precisely of its moment. I doubt it will be understood in quite the same way in a few years, when 2020 is the past instead of the near future, when self-driving cars will be common on the roads. More than the details of history, this movie works with a specific attitude to specific technologies. It’s best viewed, I suspect, at a time when cars that drive themselves are magical, when 3D printers (that make things out of apparent nothings) perhaps still have a bit of the numinous to them. Anchoring the story to the 2020 Olympics is a strong idea in that sense: a reminder to future audiences of what it was like to look forward to (what will become) everyday things.

This is a story that is precisely of its moment. I doubt it will be understood in quite the same way in a few years, when 2020 is the past instead of the near future, when self-driving cars will be common on the roads. More than the details of history, this movie works with a specific attitude to specific technologies. It’s best viewed, I suspect, at a time when cars that drive themselves are magical, when 3D printers (that make things out of apparent nothings) perhaps still have a bit of the numinous to them. Anchoring the story to the 2020 Olympics is a strong idea in that sense: a reminder to future audiences of what it was like to look forward to (what will become) everyday things.

It’s also, then, a story about the sense of wonder. About being young, as Kokone is, when the world changes. About the awe of new technology, and the ease of a young person adapting to the new. It’s about change, and so to an extent about growing up: Kokone’s decision about what to do when she graduates school is a subplot throughout the movie. But if the dream of Heartland is in a sense a dream of childhood which she’s outgrowing, it’s also a dream she works through, one in which she finds hidden meanings. Those meanings in turn allow her to change the world around her: this movie’s about a conflict of generations, and about how the old must reconcile themselves to the future.

In practical terms, it’s a well-made and well-animated film. The designs are effective in both worlds, and lend themselves to both narratives. The art’s relatively realistic, but has an overall brightness that works with the story and with the rich symphonic soundtrack. If the plot’s occasionally over-neat, the characters are strong enough to carry the movie, and some of that comes from the design and animation; these characters move enough like real people to feel credible.

In practical terms, it’s a well-made and well-animated film. The designs are effective in both worlds, and lend themselves to both narratives. The art’s relatively realistic, but has an overall brightness that works with the story and with the rich symphonic soundtrack. If the plot’s occasionally over-neat, the characters are strong enough to carry the movie, and some of that comes from the design and animation; these characters move enough like real people to feel credible.

This is, in all, an excellent story of an adventurous girl trying to understand the world around her; and it’s a story about a princess in an industrialised otherworld; and it’s a story about robots being used to fend off a giant monster that comes from the sea; and it’s a story about corporate malfeasance, and a story about the coming of new technology, and any number of other things. It’s excellent near-future SF, in the sense that it’s set at a precise time in the next few years and is primarily concerned with the effect of new technology on the world and on the characters. It’s also in part a fantasy story about another world that reflects this one in a dreamlike way. It’s not particularly challenging, and one can argue it’s not necessarily novel. But it is consistently clever, satisfying, and pleasant.

After Napping Princess I had a while to go before the short-film showcase I planned to catch next. But I had something in mind to pass the time. Coming from a movie about near-future technology, it felt appropriate to test out new-to-me technology at the Samsung VR Experience. This year I’d pass over the virtual fictions. I wanted to see how the new form could be used in a documentary. And more specifically, I wanted to see a particular thirty-minute VR documentary, Sam Dunn’s Welcome to Wacken.

After Napping Princess I had a while to go before the short-film showcase I planned to catch next. But I had something in mind to pass the time. Coming from a movie about near-future technology, it felt appropriate to test out new-to-me technology at the Samsung VR Experience. This year I’d pass over the virtual fictions. I wanted to see how the new form could be used in a documentary. And more specifically, I wanted to see a particular thirty-minute VR documentary, Sam Dunn’s Welcome to Wacken.

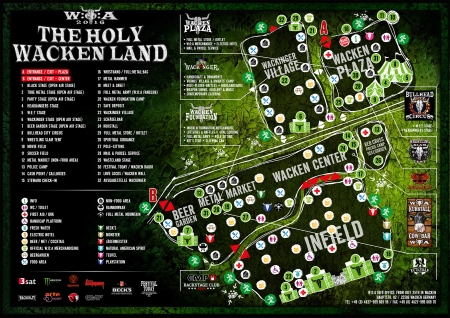

Dunn’s the premier documentarian of metal music, having followed his 2005 film Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey with the 2008 film Global Metal before going on to direct concert films and documentaries including Iron Maiden: Flight 666 and Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage. Welcome to Wacken is his latest meditation on the world of metal, about the annual Wacken Open Air metal festival that each year draws over 75 000 people to a German town of less than 2000. Strap the VR headset on, and you see a simplified map of the festival grounds. You can choose from four five-minute chapters built around interviews with festival-goers, or check out bonus content recorded at different sites around Wacken. Watch enough of this content, and you can unlock a fifth chapter.

The main documentary gives us interviews with a middle-aged couple from New Zealand who’ve come to Wacken Open Air for the first time; a Swedish man who’s part of the Warriors of the Wasteland, a kind of gladiatorial troupe at the festival; a Syrian-Canadian man who’s brought his sister to the festival; and a German man who’s been coming to the festival for nine years, and here reflects on what he’s seen at the festival and the nature of watching bands at Wacken. This chapter ends with a recording of a live performance of Arch Enemy. Then the hidden fifth chapter is an interview with the festival’s founder. The minute-long interludes also available include footage of the open field of the festival site before construction begins; a recording in a local Wacken grocery store as it’s invaded by metalheads; a recording of the Wacken merch shop; a minute recorded in the Wacken wrestling tent; and an encore performance by Arch Enemy.

The main documentary gives us interviews with a middle-aged couple from New Zealand who’ve come to Wacken Open Air for the first time; a Swedish man who’s part of the Warriors of the Wasteland, a kind of gladiatorial troupe at the festival; a Syrian-Canadian man who’s brought his sister to the festival; and a German man who’s been coming to the festival for nine years, and here reflects on what he’s seen at the festival and the nature of watching bands at Wacken. This chapter ends with a recording of a live performance of Arch Enemy. Then the hidden fifth chapter is an interview with the festival’s founder. The minute-long interludes also available include footage of the open field of the festival site before construction begins; a recording in a local Wacken grocery store as it’s invaded by metalheads; a recording of the Wacken merch shop; a minute recorded in the Wacken wrestling tent; and an encore performance by Arch Enemy.

I’m calling these things “recordings” because there’s a feel unlike most documentary footage. For the most part they’ve been recorded by static cameras — your point of view never changes, but you can look in every direction. I found, as I did last year, that the images weren’t as clear as I would have liked; having the image source so close to my eyes meant the pixellation was visible. But the ability to turn and look around was surprisingly powerful. Watching a static movie frame means always being reminded, however unconsciously, that what you’re seeing has been mediated by a director and editor. In VR, that’s not quite the case. At least with respect to the interludes, they chose the location and the footage, but what you do with it is up to you.

That’s especially true in the interludes, which frequently consist of music over fast-motion visuals. Even during the interviews, though, you can choose to focus on the interviewees or look around at the festival while they talk. It’s deeply immersive, if almost eerie — you know you haven’t been transported out of your seat, you can’t feel the sun, and yet your eyes and ears are trying to convince you that you have been put in some new place. It’s different from the usual documentary effect, perhaps more memorable if not precisely more powerful.

Particularly intriguing are the two songs performed by Arch Enemy. The footage is different from any other concert film I’ve seen. Instead of having quick cuts with cameras tracking along a rail or tilting to show the audience, the cameras here are still, and the cuts are slow. That’s because a cut in this context is more than just disorienting. The VR camera plunks you down at the side of the stage, and you see the guitarist right in front of you. You turn your head to look out over the tens of thousands of people in the crowd, then look back, squinting to see singer Alissa White-Gluz or drummer Daniel Erlandsson (almost cut off due to the stage configuration). To unexpectedly be transferred to the other side of the stage is a shock, like some malfunctioning teleportation system’s playing games with you. The experience is more immersive than the usual concert doc, even though you can’t get close-ups of the performers. It’s something much more like watching an actual live show: you stand, and look around as you like.

Particularly intriguing are the two songs performed by Arch Enemy. The footage is different from any other concert film I’ve seen. Instead of having quick cuts with cameras tracking along a rail or tilting to show the audience, the cameras here are still, and the cuts are slow. That’s because a cut in this context is more than just disorienting. The VR camera plunks you down at the side of the stage, and you see the guitarist right in front of you. You turn your head to look out over the tens of thousands of people in the crowd, then look back, squinting to see singer Alissa White-Gluz or drummer Daniel Erlandsson (almost cut off due to the stage configuration). To unexpectedly be transferred to the other side of the stage is a shock, like some malfunctioning teleportation system’s playing games with you. The experience is more immersive than the usual concert doc, even though you can’t get close-ups of the performers. It’s something much more like watching an actual live show: you stand, and look around as you like.

So much for the technology. Does it help the documentary? In this case, yes. Dunn was smart enough to choose a site-centred subject; he’s making a movie about, essentially, a specific geographic place at a specific time. Given that, he can set up his cameras and record what happens (as when a camera in the middle of a Wacken path is surrounded by an improvised circle of headbangers). You get a sense of the layout of the place that a typical documentary wouldn’t give you, and a sense of unpredictability. It’s a little like a video game, in the sense that you as a viewer have more control over what you choose to see and focus on. The chapter division and unlocking of hidden content emphasise the similarity. But then you can look at it another way: it’s like being at a festival, like being part of the crowd and craning your neck to see this or that, choosing which stage to watch at which time.

The interviews are solid, and build a sense of what the Wacken Open Air Festival means to the attendees. Particularly touching is the Syrian man who speaks about coming to Wacken with his sister, who was recently in a refugee camp; from the worst camp to the perfect camp, he says. What makes Wacken perfect? not just the music, that’s clear, but the sense of community the festival fosters. People speak about how easy it is to make friends, to get along with everyone there.

The interviews are solid, and build a sense of what the Wacken Open Air Festival means to the attendees. Particularly touching is the Syrian man who speaks about coming to Wacken with his sister, who was recently in a refugee camp; from the worst camp to the perfect camp, he says. What makes Wacken perfect? not just the music, that’s clear, but the sense of community the festival fosters. People speak about how easy it is to make friends, to get along with everyone there.

Sometimes that feels overstated. One of the interviewees insists that there are no politics at Wacken, and if you can see why he thinks that, it’s a little difficult to be sure that’s a universal sentiment when the interlude from the wrestling tent features a villain named “Sultan.” There’s an overall sense here, for better or for worse, of a libertarian ethos without much thought behind it, as though this were a space for people playing at a game of freedom. In contrast to that pseudo-libertarianism is the importance the interviewees give to the idea of community and of fellowship. There’s an unstated and indeed almost unobserved tension there, and it may be that the identity of the festival derives from the creativity of that tension.

And, of course, the music. The German interviewee observes that there’s something unexpectedly “hippie-ish” about the feel of the festival. There are gladiators and wrestlers, but in his telling, there’s a sense of peace as well. He speculates that the music’s a way to get fears out, to work through what frightens you in a group experience. It’s a persuasive idea, explaining the sense of closeness people describe among a crowd of tens of thousands. If so, it’s also an explanation for why the festival’s so important. For what the thing means.

To capture that unlocking of meaning is the goal of most documentaries, not just through the analysis brought in an interview, but in the presentation of experience. Welcome to Wacken manages that, describing place and why the place is important. It’s an excellent use of new technology, embracing the non-linear to get at a specific sensation.

Two films to start the day, then, with more to come. There’s a line in Welcome to Wacken where one of the interviewees mentions a theory that the Wacken festival is the only real thing in the world, and all the rest of the year is just an illusion. I can understand that; Fantasia takes on something of that feel, a reality more heightened than the other 49 weeks around it. By the middle of that Saturday I was well immersed in it. And the only way out, thankfully, was to go on through. Which I then proceeded to do.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.