How I Spent My Summer Vacation

|

|

|

On May 25th I finished my thirteenth year at the small private school where I teach fourth grade. I love my job and I love my students, but remember the transports of joy that you felt when you were a kid, when the dismissal bell finally rang on that last day of school? I can assure you that your happiness was as nothing compared to the incandescent elation teachers feel on that final afternoon of the second semester.

At my school, we get eight weeks off, and I spend them much as I did when I was in school myself — I make a big stack of paperbacks and I read as many of them as I can before the next school year begins. Last summer, for some perverse reason I no longer remember, I changed my routine a bit; instead of tearing through the usual pile of science fiction/fantasy/mystery yarns, I decided to take on a different kind of book: David Foster Wallace’s postmodern magnum opus, Infinite Jest. Though it is itself marginally science fiction, Wallace’s massive novel is about as far removed from the kind of genre reading that usually fills my vacation as it is possible to get. I originally had some notion of doing a fair amount of my “normal” summer reading alongside of Infinite Jest, but it didn’t work out that way. I’m glad I read the novel, but it absolutely exhausted me; after hewing my way through thirty or forty pages I barely had enough physical and mental energy to hoist myself out of my chair, much less crack open a gaudy-covered Ace reprint of Radium Raiders of Deneb by Lester Cragwell Griggs.

If you’ve never tackled it, reading Infinite Jest is like driving coast-to-coast on a state of the art superhighway… that has a speed bump every fifty feet, for three thousand miles. I did manage to get Son of Tarzan read in between bouts with Wallace’s knotted prose, but the two books didn’t mix well, and left me feeling slightly seasick, not to mention somewhat confused about the nature of reality.

In any case, this year I was determined to return to sanity and my standard procedure and see if it’s possible to overdose on the heady fumes that waft from the pages of forty year old paperbacks. I now submit the results of my experiment for your edification… or, if you wish, to act as a grim warning.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

|

|

|

I aimed to get twenty four books read in eight weeks, but I didn’t quite make it; I finished with twenty two, which is still not bad. After all, vacation or no, I am still a responsible adult with all of the duties and obligations that go along with that status. I had to do some grocery shopping, the car needed attention, I emptied and reloaded the dishwasher once or twice a day (apparently I’m the only one around here who has the launch codes) and I mowed the lawn four or five times. Also, I just ran out of gas the last week or so; I neglected the last couple of books on the pile and finished by watching a lot of Hawaii Five-O. (The original, of course.)

|

|

I’m not going to belabor you with an account of every book I read; there’s really not much to say about rote Burroughs pastiches like Lin Carter’s Zanthodon or Alan Burt Akers’ The Suns of Scorpio, or about one more link in a series chain like E.C. Tubb’s Eloise (though I did like that one), or about pure pulp incoherencies like Abraham Merritt’s Seven Footprints to Satan or Jack Williamson’s Golden Blood. There were some books, though, that lifted the summer reading to a somewhat higher level. Here are five of the best of them.

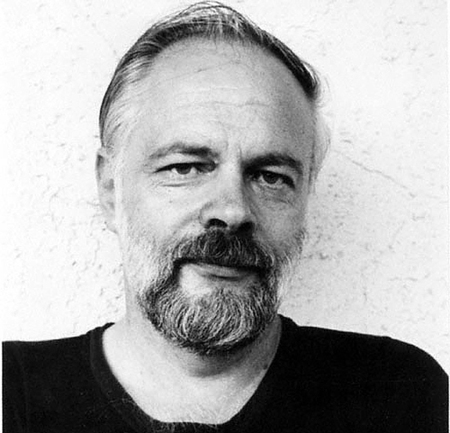

I found Philip K. Dick’s 1977 novel A Scanner Darkly to be one of his finest books, and since he’s the man who wrote UBIK and Martian Time Slip and Confessions of a Crap Artist, that’s really saying something. (Scanner probably seemed even better to me coming right after Zanthodon.) In a near future Southern California, undercover narcotics agent Robert Arctor spends half his time masquerading as Fred the drug dealer and the other half ratting on Fred’s lowlife associates to his police superiors. As the powerful drugs that Arctor is compelled to consume to maintain the credibility of his Fred identity take their toll on his brain, the line between identities blurs and ultimately dissolves until there’s not enough left to constitute a single person, much less two. Dick’s wild inventiveness and deep humanity are on full display here. The story’s main science fiction conceit is the scramble suit, a “multifaceted quartz lens hooked to a miniaturized computer whose memory banks held up to a million and a half physiognomic fraction-representations of various people,” which are projected onto a “shroudlike membrane” which completely covers the wearer. No one clothed in such a suit can be identified – and as a security measure, all members of the narcotics police wear them when contacting anyone else in the organization. Hence, Robert Arctor can never know who any of his colleagues really are. Indeed, such a technology must erode even as it conceals; someone subject to it will eventually be no more sure of the “I” who is speaking any more than he is of the “you” he is speaking to; in A Scanner Darkly, no center of certainty can hold.

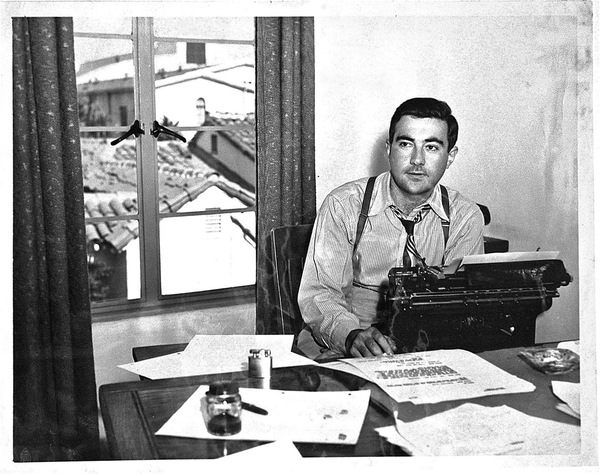

Philip K. Dick

The science fiction in the book is mostly at the edges; it is primarily an intensely human story about how the acid bath of modern life eats away at identity and autonomy until we scarcely know who we are or where we stand, and its picture of a culture of surveillance is chillingly prophetic. (It’s especially odd to reflect that this compelling nightmare appeared in 1977, the same year that gave us the pure escapism of Star Wars.) It has beautiful passages of such deeply felt emotion and heartbreak that I frequently stopped to reread a couple of paragraphs or a couple of pages; I just wanted to savor them again, and make sure that I was wringing every drop of meaning out of what was there. It had obviously cost Phil Dick so much to write this book, I felt like I owed it that kind of attention. This is not a response I commonly have to old science fiction stories, but this man didn’t write just any stories.

Oddly enough, A Scanner Darkly shares some elements with Infinite Jest, as both feature a fragmented, disintegrating world filled with shadowy government conspiracies and anti-human values, chemically altered personalities, and hopeless, lonely, powerless people adrift in a reality so shifty that chronic uncertainty about everything is the default position. However, Dick managed to get his point across in three hundred pages instead of a thousand and all without giving me even one headache, much less sixty of them.

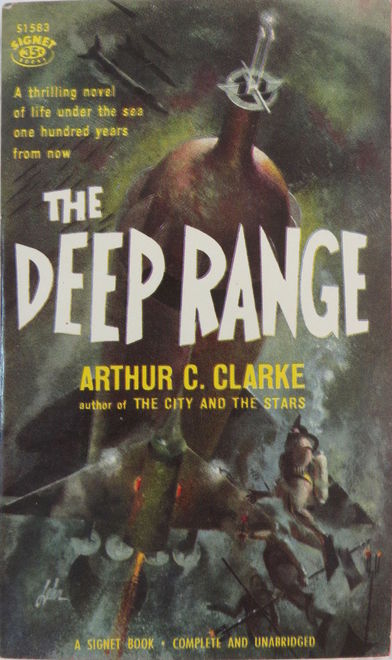

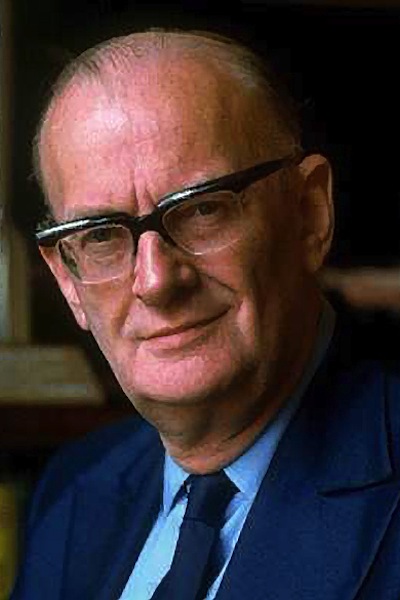

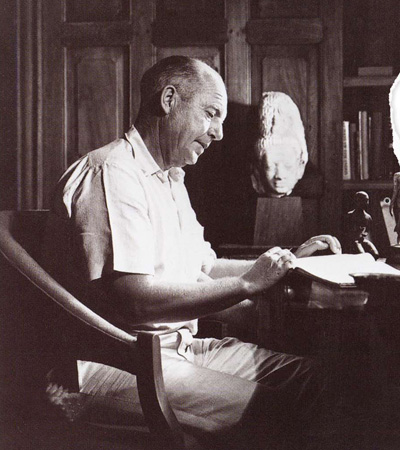

Arthur C. Clarke

The Deep Range by Arthur C. Clarke is a different kind of vision altogether. It’s bit of a science fiction anomaly, as it is not an outer space tale, but is set in that poor relation of SF venues, the sea. The book follows the career of Walt Franklin in the oceans of the future, as he shepherds the vast herds of whales that are used to feed the world’s hungry billions. (The popular term for such undersea troubleshooters is “whaleboys” – really! It’s a charming feature of Clarke’s scientific bureaucracies that ordinary people are so interested in them that they give colorful nicknames to such organizations’ minor functionaries.)

The book was written in 1957, so there are no hints of cetacean rights or intelligence, but don’t get too upset. Walt never does feel quite right about the carnage (especially after a Buddhist sage prompts him to make a stomach-churning visit to a processing plant), and one of the main plot points involves Franklin’s successful efforts to convince his organization to abandon whale meat for whale milk. The story’s core assumption is an upbeat one that is common to most of Clarke’s work – the emergence of a benevolent world government that will use technology to rationally and frictionlessly solve all problems and make everybody pretty damn happy. It doesn’t appear to be working out that way in this fabulous future that we’re all actually living in, but it’s hard to not feel that Clarke’s vision is how the world should be. (The three sections of the book, following Walt’s career progression, are titled “Apprentice,” “Warden,” and “Bureaucrat,” and Clarke thinks that’s just fine – heroic, in fact. That tells you a lot about his organizational optimism.)

|

|

Despite the book’s unrealistically sunny view of large institutions, I thoroughly enjoyed it. I’ve read a lot of Clarke over the past few years after neglecting him in my younger days and my regard for him continues to grow with each book. His work is chock full of science (which is often thoroughly outdated — which isn’t his fault), but it’s never dry because Clarke was a passionately obsessed man, and his obsession was with what might be called the romance of fact. Indeed, I’ve come to believe that he was the best balanced of the giants of 20th century science fiction, more realistic and factual than Bradbury, more lyrical and poetic than Asimov, and less dogmatic and more humane than Heinlein. The Deep Range is one of his best books.

|

|

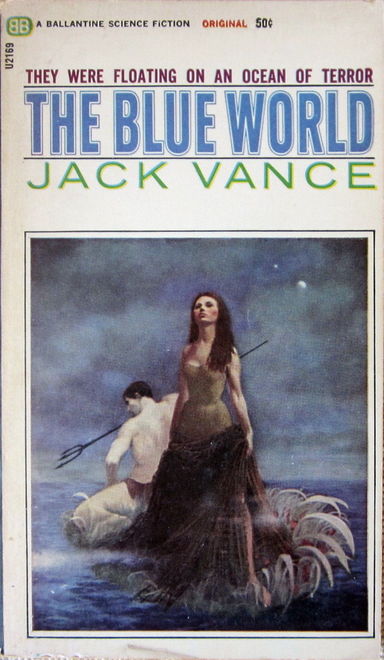

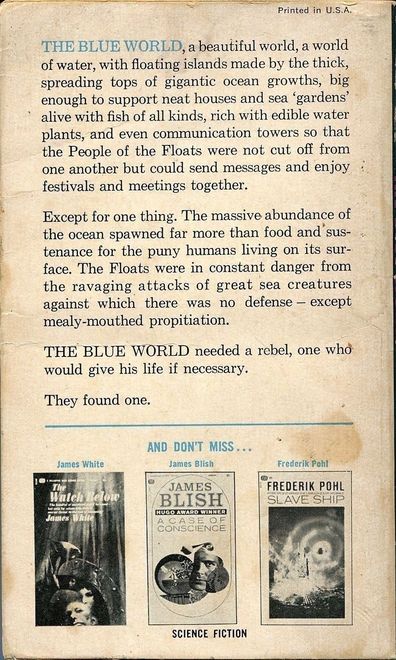

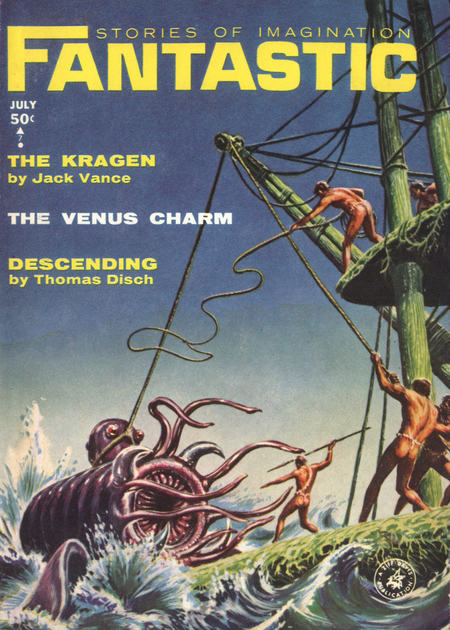

Once you’ve jumped in the pool and gotten wet, you might as well stay in for a while, so if you’re the sort of person who roots for Captain Ahab you’ll love Jack Vance’s 1966 fish-killing fantasia, The Blue World. On an unnamed planet that’s completely covered by water, the descendants of the passengers of a crashed interstellar prison ship live a placid existence on the island-like tops of huge sea plants. All that’s left of their origins are their caste names (Bezzlers, Swindlers, Malpractors, Smugglers, Incendiaries, etc.) and the fragmentary writings the original generation left behind as a record of their struggle to live on this watery world, writings that have now, hundreds of years later, acquired the status of holy texts. (There is of course an exegetical caste whose task is the interpretation of these handwritten notes.) The planet’s climate is mild and with a bit of ingenuity the ocean provides for the community’s every need. There’s just one problem — the enormous, whalelike creature called King Kragen. This beast swims up periodically and must be placated with a share of the food the community has raised, lest his wrath be aroused. (Need I say that there is a caste of priests who codify and officiate over the people’s service to this finny god?)

Jack Vance

All in all though, things run fairly smoothly — until a rebel arises, Sklar Hast of the Hoodwink caste, who sees no reason for this degrading service to continue. Soon the headstrong iconoclast has the community in an uproar, and by the end of the book has provoked the reorganization of society, the advancement of long-dormant technology, and ultimately the dismantling of the priestly class and the destruction of King Kragen. (Not to mention the incidental deaths of a fair number of folk who were reasonably content with things the way they were, but that’s progress; you can’t make a sea-omelette without squeezing a few sponges.)

Cover by Emsh

The writing is mordantly dry and witty in Vance’s best baroque manner, the invention is continuously ingenious, and the satire is sharp without being too heavy-handed. It doesn’t all run one way, either. In his perfect willingness to wreak some death and destruction in order to fulfill his vision, Sklar Hast is not an entirely benign character, and it is possible to wonder just what the wholesale “improvement” of this society will finally result in. Is Sklar Hast a heroic, progress-bringing Prometheus… or the serpent in the garden? Doubtless most of those who first encountered the tale in the pages of Fantastic Stories (where it appeared as “The Kragen” in July 1964) read it the first way, but Vance leaves enough room to reasonably pick the second interpretation. Ah well. Of the wrangling over the meanings of sacred documents, there is no end…

|

|

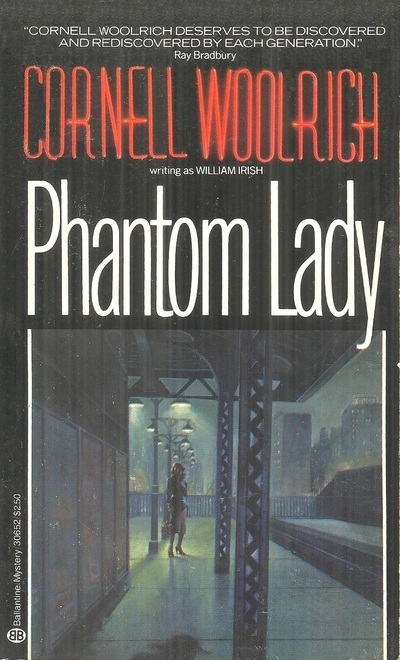

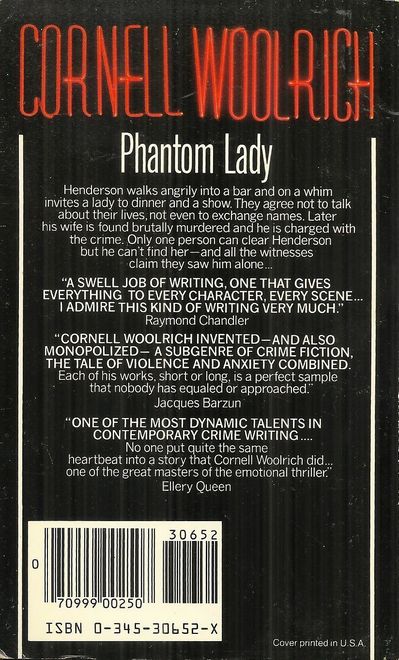

Back on dry land, in the realm of suspense, few names are greater than Cornell Woolrich, and his 1942 novel Phantom Lady (originally published under the name William Irish) is reckoned one of his best works. It’s just that, after reading it, I’m not sure what that accolade really signifies. The story is essentially quite simple; Scott Henderson has an argument with his wife and storms out of their apartment. In a bar down the street, he meets a woman and offers her the evening he had planned for his wife — dinner and a show. She accepts, with one condition: no names, no personal information of any kind. Scott accepts, spends the time barely noticing his companion (he’s still so upset about the fight) and when he returns home finds his apartment filled with police. His wife has been murdered. You can fill in the rest for yourself. All the evidence points to Scott, and his only alibi is a woman he never saw before and knows nothing about. Not only can the police not locate her, everywhere they check — bar, restaurant, theater — everyone says Scott was alone. No one remembers seeing a woman. Scott is tried, convicted, and sentenced to death, and Woolrich tightens the screws with his very chapter headings, all of which are simply a countdown to the fateful day: “The Eighty-Seventh Day Before the Execution,” “The Twenty-First Day Before the Execution,” “The Tenth Day Before the Execution,” and so on.

|

|

Phantom Lady shows Woolrich at his best and at his worst. The suspense is undeniable but is achieved so mechanically that it’s hard to fully enjoy it; I often felt blatantly manipulated and came to resent it a bit. (I had the same response to the only other Woolrich I’ve read, The Bride Wore Black. He was not the kind of writer who was interested in concealing his machinery.) I can’t deny that by the time the execution countdown was in the single digits I was turning the pages so fast I risked paper cuts, but the actual resolution of the mystery is jaw-droppingly absurd (what’s the cube root of implausible?), and though Scott Henderson is exonerated it is without the help of his mysterious date. That’s fine, but then Woolrich fumbles at the goal line by unnecessarily revealing the identity and fate of the phantom woman. Since Scott ultimately gets off the hook without her help, it would have been much better if we finally knew no more about her than he did, if she were allowed to anonymously disappear back into the faceless city, to remain a permanent, unsolvable enigma. Woolrich would have done well to have heeded Saverchell Sitwell, who said, “In the end, it is the mystery which lasts and not the explanation.” And really, when you have to end your book with an unbroken twenty page monologue by a character who stands in the middle of a room and explains every single thing that happened, you have an unresolved structural problem, to say the least.

Cornell Woolrich

But then… there are things in Phantom Lady that I’ll never forget, chief among them a long chapter in which a young woman (Scott’s girlfriend — he was trying to persuade his wife to grant him a divorce so he could marry her) drives a man (the bartender at the bar where Scott met the mystery woman) into a blind panic by simply sitting at the bar and silently, intently staring at him. When he leaves the bar at the end of his shift, she follows him, matching him step for step and turn for turn until he fears he’s about to lose his mind. In plot terms, she’s trying to break him down and get him to tell why he lied to the police about not seeing Scott’s companion, but for the space of this chapter I forgot all about Woolrich’s clanking, manipulative plot. The silent, enigmatic pursuit through the echoing late night streets, alleys, staircases, and elevated train platforms of the vast, indifferent city was absolutely riveting and could stand as the distilled essence of noir. When the frantic man, crazed by his terror of this quiet, passive nemesis, seeks to escape her by bolting across a street and is hit and killed by a truck, I felt like I had read something worthy of Poe or Kafka. Despite the book’s faults, scenes like that will ensure that Phantom Lady will haunt me for a long time.

Cornell Woolrich, while still well known among mystery aficionados, hasn’t yet made the big leap into the college syllabus, but Jim Thompson has come a long way. All of his novels were originally published as paperback originals, many of them by Lion Books, which was about as low as you could get. (Lion catered to what used to be known as the Raincoat Trade.) Now that Thompson is many years dead he’s a critical darling and has appeared in the Library of America. And some people say there’s no such thing as progress. His 1952 thriller The Killer Inside Me is a perfect example of his unique perspective, a kind of American gutter nihilism.

Jim Thompson

Everybody likes Lou Ford, deputy sheriff of the small West Texas town of Central City. Lou is the epitome of good humored affability. He’s friendly, helpful, sympathetic, and a good listener. He really has a way with people, right up until the minute he kills them. Lou narrates his own story, and his voice is so modestly natural and unaffected you can’t help but cotton to him, as they say in his part of the country. That’s why it’s so deeply shocking when, in his affable, easygoing, good humored way, he tells you how he murdered a prostitute that he was friends with along with the son of a local businessman and set things up to look like they killed each other, and then murdered a troubled teenage boy he genuinely liked and had tried to steer clear of trouble, because the first story started to unravel and he needed someone to take the fall for the first two deaths.

Each killing seems to have less rationale than the one before it, and when Lou gets around to murdering his childhood sweetheart and fiancee, even he realizes that the reasons are starting to get mighty thin. Amy Stanton had to die… why? Lou is sure that she poses a threat to him somehow, but he can’t quite remember how, exactly. Maybe that’s why that murder was a hard one to do, and a hard one to talk about, but then the drifter — that one’s easy. He’s the one he can pin Amy’s death on. And so it goes on, until gradually Lou becomes aware that people are looking at him oddly, and that his grin and aw-shucks manner and cliche-filled patter has stopped fooling anyone. They know. And that’s OK too, because all along Lou has had one real goal — to destroy everything, by destroying himself. Late in the book, Lou relates an anecdote that has no overt connection to the characters or plot of the actual story, but that tells us everything we need to know about him and the world Jim Thompson created for him. Lou tells about a prosperous Central City jeweler, a man who had financial success, social position, a wife and children, and even a mistress on the side, a good looking girl who knew her place and was never going to cause any trouble:

So everything was perfect. He had her and he had his family and a swell business. But one morning they found him and the girl dead in a motel — he’d shot her and killed himself. And when one of our deputies went to tell his wife about it, he found her and the kids dead, too. This fellow had shot ’em all.

Then Lou Ford — or Jim Thompson — points the moral: “He’d had everything, and somehow nothing was better.” When The Killer Inside Me comes to its apocalyptic conclusion, that yawning abyss is all we’re left with. At the center of every one of Thompson’s books, there is — if you will permit the contradiction — a hard core of nothingness. Let other, slicker writers churn out their die-cut zombies and vampires and demon-channeling detectives and suave, sophisticated serial killers; we know they’re only kidding. They don’t mean a word of it. But the hungry void was real to Jim Thompson; he fought it his whole life. That’s why he remains the most frightening writer I know of, and The Killer Inside Me is truly the stuff of nightmares.

I read several other fine books over my break that I’d love to talk about — Hestia by C.J. Cherryh and Castaway’s World by John Brunner and The Big Clock by Kenneth Fearing and Necromancer by Gordon R. Dickson and Guards! Guards! by Terry Pratchett, but you’re probably as worn out by now as I was on that last day of school; I’m practically there myself, and I have a pile of papers to grade. So until next summer…

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of The Nutty Professor.

Always interested when I see something about Jim Thompson. His stories (most of which are very good) are so bleak. Pop 1280 is another favorite of mine.

The author photo of Woolrich is actually David Goodis, who was another unique and troubled writer.

Doh!

I don’t think we’ve had a retro-review of that issue of Fantastic. Maybe one of these days…..

Great write-up! I had the same reaction as yours to KILLER INSIDE ME and I, too, enjoyed Vance’s Blue World.

I’ll add to your shout out for THE BIG CLOCK. A great thriller. I think they later based a suspense movie off of it, updating the time and changing the setting, NO WAY OUT, with Kevin Costner.

Howard, they filmed it in (I think) 1945 as The Big Clock, with Ray Milland and Charles Laughton as Earl Janoth. The movie isn’t all that successful, in my opinion – it has a odd, semi-comic tone. Laughton is excellent, though.