Fantasia 2017, Day 6: Twice-Told Tales (Animals, Wu Kong, and House of the Disappeared)

Tuesday, July 18, I set off for Fantasia with another full day before me. I planned to watch three films for which I had three different expectations. First was Animals (Tiere), a German film promising surrealism and artfulness. Then the Chinese big-budget special-effects blockbuster Wu Kong. Finally, and perhaps most intriguingly, House of the Disappeared (Si-gan-wi-ui-jip), a Korean horror movie based on a Venezuelan movie called The House at the End of Time (La casa del fin de los tiempos) which I’d seen three years ago during my first year covering Fantasia; I couldn’t help but wonder how that film would translate across cultures.

Tuesday, July 18, I set off for Fantasia with another full day before me. I planned to watch three films for which I had three different expectations. First was Animals (Tiere), a German film promising surrealism and artfulness. Then the Chinese big-budget special-effects blockbuster Wu Kong. Finally, and perhaps most intriguingly, House of the Disappeared (Si-gan-wi-ui-jip), a Korean horror movie based on a Venezuelan movie called The House at the End of Time (La casa del fin de los tiempos) which I’d seen three years ago during my first year covering Fantasia; I couldn’t help but wonder how that film would translate across cultures.

First was Animals. Directed by Greg Zglinski from a script by Jörg Kalt that was rewritten by Zglinski, it begins by introducing us to Nick (Philipp Hochmair) and Anna (Birgit Minichmayr), a couple whose marriage is under severe strain. Nick’s a chef who may be conducting an affair with an upstairs neighbour. Anna’s a writer trying to start a new novel but facing a creative block. They plan to go off to an isolated cottage in Switzerland, where Nick will try the local cuisine and Anna will focus on her book; in the meanwhile their apartment will be watched by Mischa (Mona Petri, who plays several roles). Strange things happen during the getaway, particularly following an accident on the road when Nick hits a sheep. The movie cuts between the couple and Mischa, as impossible events unfold, challenging time, space, cause, and effect.

The movie’s well-crafted. It has a polished look, with textured lighting and what ought to be a strong sense of atmosphere. And yet I wasn’t convinced. We get a host of strange things happening, from mysterious locked rooms to talking animals to a woman throwing herself out a window and vanishing. And yet none of them cohere. When we get some sense toward the end of the movie why we’re seeing all these strange things, the explanation feels slack. Not only is there no rational logic to what we watch, there’s no emotional logic either.

It is possible to come up with various explanations for events. In the days after this movie screened, I spoke with a number of people who had different interpretations for the dream-logic in the film. Many of them liked Animals much more than I did. Despite all the explanations I heard, though, I still can’t find a way to make the movie cohere for me. That is, I can’t find a way to make the weirdness of the movie, in which characters experience time at different rates and in which geography grows steadily more confused, reveal character in any meaningful way. I feel that in the end there’s a slackness to the film, not the tautness that would pay off the surrealism we see unfold.

It is possible to come up with various explanations for events. In the days after this movie screened, I spoke with a number of people who had different interpretations for the dream-logic in the film. Many of them liked Animals much more than I did. Despite all the explanations I heard, though, I still can’t find a way to make the movie cohere for me. That is, I can’t find a way to make the weirdness of the movie, in which characters experience time at different rates and in which geography grows steadily more confused, reveal character in any meaningful way. I feel that in the end there’s a slackness to the film, not the tautness that would pay off the surrealism we see unfold.

I believe the movie’s meant to be an expressionistic look at the emotions of its characters, and that the motifs which recur throughout the film are meant to bring out the essence of who they are. But I also think the blurring of time and place tends to obscure rather than reveal. I think the paradoxes and varied perceptions of the characters don’t resolve into a meaningful symbolism, or at least no symbol-system I could grasp at one viewing. I also think that the visual style of the movie, cool and precise, tends to work against the feel of surrealism: the movie’s too crisply machined to ultimately create an atmosphere. So while I can see the technical accomplishment of the film, I’m not impressed enough with it in purely visual terms to feel that the experience (even at a terse 95-minute run time) is worth the viewing.

It is of course quite possible that I’m simply not the right audience for this film. I found myself confused early on, when Anna and Nick are driving in daylight to their rented house, pass through a tunnel, and emerge into nighttime. I thought that looked back to the first shots of the movie, and the camera gliding through a red-lit tunnel; but there hasn’t been any trigger for reality to begin blurring at this point. Still, it’s after the tunnel that we get the first cut-away back to Mischa, and after the tunnel that we first see Anna and Nick dreaming. As dreams become harder and harder to separate from the reality we’re seeing, this feels like it ought to be important, especially since the dreams run impossibly parallel. If so, what’s happening?

It is of course quite possible that I’m simply not the right audience for this film. I found myself confused early on, when Anna and Nick are driving in daylight to their rented house, pass through a tunnel, and emerge into nighttime. I thought that looked back to the first shots of the movie, and the camera gliding through a red-lit tunnel; but there hasn’t been any trigger for reality to begin blurring at this point. Still, it’s after the tunnel that we get the first cut-away back to Mischa, and after the tunnel that we first see Anna and Nick dreaming. As dreams become harder and harder to separate from the reality we’re seeing, this feels like it ought to be important, especially since the dreams run impossibly parallel. If so, what’s happening?

I haven’t got an answer. In this as in much else, the movie feels random. There’s a point while driving when Anna and Nick play a word game, coming up with authors’ names to match a random letter. We hear them mention Bulgakov and Baudelaire — but if there’s a point to these references, I can’t see it, and can’t find elements in the movie echoing the works of either writer.

There are enough motifs in the movie that it’s maddeningly close to making sense. A bird impossibly crashes through a window and beats itself to death against a wall; Anna says “Animals don’t kill themselves,” and we think back to a scene early on in which a woman throws herself out a window and vanishes. So suicide is a possible theme. Nick’s a cook, and we see him preparing the sheep he hits with his car; that sense of life as meat, of death as part of animal life, feels central — and yet never, to me, crystallises into something meaningful. Things repeat: locked rooms, one in Anna and Nick’s apartment forbidden to Mischa, and another in their cottage that Anna can’t get into. Nick hits a sheep with his car early in the movie, and then again later. It all has a dream-logic, the way a dream can circle around an incident and replay it with different set-ups, and it’s a good structural idea. But I can’t find a way to connect it to any deeper insight into character.

There are enough motifs in the movie that it’s maddeningly close to making sense. A bird impossibly crashes through a window and beats itself to death against a wall; Anna says “Animals don’t kill themselves,” and we think back to a scene early on in which a woman throws herself out a window and vanishes. So suicide is a possible theme. Nick’s a cook, and we see him preparing the sheep he hits with his car; that sense of life as meat, of death as part of animal life, feels central — and yet never, to me, crystallises into something meaningful. Things repeat: locked rooms, one in Anna and Nick’s apartment forbidden to Mischa, and another in their cottage that Anna can’t get into. Nick hits a sheep with his car early in the movie, and then again later. It all has a dream-logic, the way a dream can circle around an incident and replay it with different set-ups, and it’s a good structural idea. But I can’t find a way to connect it to any deeper insight into character.

Admittedly, I also found Nick and Anna uninteresting as characters. They’re individualised, and Nick’s sense of determination is reasonably distinctive; in more ways than one, he’s a man with an interest in meat and flesh. But there’s no sense of satisfaction to him at any point in the movie, no hint he ever feels or has felt accomplishment. Anna, meanwhile, is a blank as novelists go. There’s no sense of her as a creative force, blocked or not, and no sense that I could catch of her previous work informing who she is. Worse than any of this, neither Anna nor Nick engage with the surreal things around them in a credible way, caught between not acknowledging the weirdness (primarily Nick) and accepting it too quickly without investigating what’s happening (primarily Anna). Presumably there’s a reason for this bound up with the cause of the weirdness, but it’s estranging in a way that serves no obvious purpose.

The lack of connection to character undermines much of what should be effective in the movie. The visuals, all the cool colours and harsh unforgiving faces, remain unengaging. Shots of brooding city buildings and misty mountain vistas fail to impress because they remain random elements in an overall random story. I wonder whether this has to do with the story behind the film: Joerg Kalt, who wrote the screenplay, committed suicide in 2007; Greg Zglinski had read it the year before, and after Kalt’s death decided to make the film because of the power of the script. Zglinski rewrote the script, though, and I wonder whether in doing so he imposed a more purely visual sense over a logically coherent symbolism. He may not have; but some of his comments in his interviews imply a greater concern with the feel of the thing than with coherence.

The lack of connection to character undermines much of what should be effective in the movie. The visuals, all the cool colours and harsh unforgiving faces, remain unengaging. Shots of brooding city buildings and misty mountain vistas fail to impress because they remain random elements in an overall random story. I wonder whether this has to do with the story behind the film: Joerg Kalt, who wrote the screenplay, committed suicide in 2007; Greg Zglinski had read it the year before, and after Kalt’s death decided to make the film because of the power of the script. Zglinski rewrote the script, though, and I wonder whether in doing so he imposed a more purely visual sense over a logically coherent symbolism. He may not have; but some of his comments in his interviews imply a greater concern with the feel of the thing than with coherence.

To me the surrealism of the finished piece undercuts character. The sense of the relationship between Anna and Nick falls flat because we don’t know what to believe. Meanwhile, Mischa’s story never comes alive, even if it ultimately ties in to Nick’s plot and one of the strange opening shots. As a viewer, I don’t need a precise explanation for everything I see. But I do need some kind of structure for a story, some sense of why things flow in the order they do, how the symbols I’m seeing onscreen relate. That’s lacking here, at least after one viewing. And I can’t say the nice photography’s enough of a reason for me to want to see the movie again.

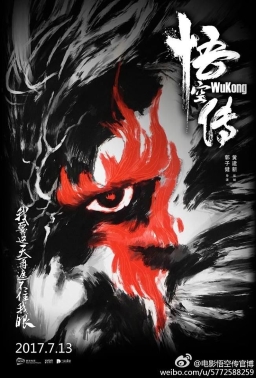

A complete change of pace was next, with director Derek Kwok’s Wu Kong. Based on Hezai Jin’s internet novel of the same name (which some sources give as Legend of Wukong, and which appeared online in 2000 with a print version appearing in 2001), the movie boasts a script written by Kwok, Hai Huang, Fan Wenwen, and Henri Wong. Sun Wu Kong, the Monkey King, AKA Monkey (by his own account also called “The Great Sage Equal to Heaven”), is a trickster in Chinese myth and folktale who famously appears in the classic novel Journey to the West. This story’s different, a tale from earlier in the Monkey King’s career. Here we see him (incarnated by Eddie Peng) infiltrate heaven and sneak into the Academy of Destiny, which houses the Destiny Astrolabe that orders the heavens and the earth. Misadventures and spectacular combat ensues. Wu Kong comes to an uneasy peace with the immortals of the Academy, but how long can that last?

A complete change of pace was next, with director Derek Kwok’s Wu Kong. Based on Hezai Jin’s internet novel of the same name (which some sources give as Legend of Wukong, and which appeared online in 2000 with a print version appearing in 2001), the movie boasts a script written by Kwok, Hai Huang, Fan Wenwen, and Henri Wong. Sun Wu Kong, the Monkey King, AKA Monkey (by his own account also called “The Great Sage Equal to Heaven”), is a trickster in Chinese myth and folktale who famously appears in the classic novel Journey to the West. This story’s different, a tale from earlier in the Monkey King’s career. Here we see him (incarnated by Eddie Peng) infiltrate heaven and sneak into the Academy of Destiny, which houses the Destiny Astrolabe that orders the heavens and the earth. Misadventures and spectacular combat ensues. Wu Kong comes to an uneasy peace with the immortals of the Academy, but how long can that last?

The correct answer is “not long at all,” and Wu Kong’s own refusal to take any slight helps propel an otherwise episodic plot. Luckily, this version of the character’s charismatic enough to keep us involved, angry and goofy and wiseass by turns. This is a kind of mythic super-hero story that’s arguably closer to Jack Kirby’s sensibility than anything yet to come out of the Marvel factory. If it’s structurally a little similar to the first Thor movie, moving from the heavens to the Earth for some lower-power running-around before returning to the heavens for a final slam-bang confrontation, it is nevertheless quite a different animal. This movie’s Earth is different, to start with, a village set in a vague ancient time rather than the everyday world somewhat awkwardly mixed into myth. Maybe more to the point, Wu Kong’s learning a different lesson.

Sun Wu Kong is one of the world’s great mythic trickster figures, but we don’t necessarily see that here in the way we might expect. There’s a certain amount of braggadocio, and a certain amount of hapless misfortune. But there’s also a kind of direct confrontational streak to his personality. That’s a perfectly viable interpretation of the quarrelsome Monkey King, and it stands out in sharp contrast to, say, Donnie Yen’s recent more comical turn as the character (in 2014’s The Monkey King and 2016’s The Monkey King: The Legend Begins, both directed by Pou-Soi Cheang). As I said, it keeps the film moving, and the power Sun Wu Kong commands means the earth-shaking stakes are clear even as his more-than-occasional missteps make him flawed, vulnerable, and oddly sympathetic. Again, that’s a good contrast to the relatively brutal iteration of the character played by Bo Huang in the 2013 Journey to the West. Like that movie, this one shows us Sun Wukong before the novel really begins — but here he’s basically good-hearted, if confrontational and violent.

The 2013 movie was co-directed by Kwok and Stephen Chow; a sequel, Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back, was released earlier this year without Kwok’s involvement, directed by Hark Tsui, written by Chow with Si-Cheun Lee, and starring Kenny Lin as Sun. I know nothing about the behind-the-scenes story that led Kwok to return to the character in what is effectively a different franchise; in any case the tone here is different from his Journey to the West, which I thought both more comedic and much less effective (although for whatever reason I seem to be entirely immune to the appeal of Stephen Chow, so there is that). There are gags here, but also a relatively serious tale of rebellion and heavenly authority.

The 2013 movie was co-directed by Kwok and Stephen Chow; a sequel, Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back, was released earlier this year without Kwok’s involvement, directed by Hark Tsui, written by Chow with Si-Cheun Lee, and starring Kenny Lin as Sun. I know nothing about the behind-the-scenes story that led Kwok to return to the character in what is effectively a different franchise; in any case the tone here is different from his Journey to the West, which I thought both more comedic and much less effective (although for whatever reason I seem to be entirely immune to the appeal of Stephen Chow, so there is that). There are gags here, but also a relatively serious tale of rebellion and heavenly authority.

Worth noting that one doesn’t need to know any of the various stories of Sun Wu Kong to enjoy this movie. There are, of course, nods to his legend, from peaches of immortality to the presence of his rival, brooding yet often-befuddled Erlang Shen (AKA Jian Yang, played under any name by Shawn Yue). Sun begins the movie with his trademark iron staff already in his possession, but it’s the sort of given one picks up on as the movie goes on. More potentially troubling is an extensive voice-over infodump setting up the story with a complex creation myth. And yet even the potentially-intimidating detail resolves itself into an easily-grasped structure.

The special effects here are strong, imaginative, effective, and occasionally beautiful. Scenes in the Academy of Destiny in particular are high fantasy that still feels credible and tangible enough to work. The acting, beyond Peng’s star turn, is perfectly solid — notably Yue’s Erlang Shen. The fights are quick and well-choreographed, often with an effective slapstick edge, and integrating the visual effects very nicely. The plot moves efficiently, and if a scheme midway through to trick a cloud demon feels unlikely, it can reasonably claim something of the improbable whimsy of folklore.

Similarly, if the characters feel a bit bigger than the movie, it nevertheless works: you feel they have lives outside this story. Which is of course the case. It’s a blockbuster with deep roots, in folklore and in one of the classic novels of world literary history. But it’s also, and primarily, a crowd-pleasing epic with jokes and fight scenes and eye-popping special effects. There’s no sense of preciousness; compared with American blockbusters, I find less fanservice here, less of an attempt to demonstrate ‘respect’ for the characters. One can argue whether Chinese or American blockbusters are more standardised — which hews more closely to an established structure, to a predefined vocabulary of plot twist and character development and banter. I can say only for myself that of the summer epics I’ve seen in the last few years, quite aside from the question of which I’ve enjoyed or which I think are better movies, on the whole the Chinese ones feel more free, and are more different one from another. I’ve seen three movies from the last few years involving Sun Wu Kong in a major role (four counting the two Donnie Yen movies separately), and they each have a different tone and do different things with the character. This movie’s the one that entertained me the most, the one that best captured the feel of a thrill-ride, the one that felt most dramatic. It tries to entertain; it succeeds.

Similarly, if the characters feel a bit bigger than the movie, it nevertheless works: you feel they have lives outside this story. Which is of course the case. It’s a blockbuster with deep roots, in folklore and in one of the classic novels of world literary history. But it’s also, and primarily, a crowd-pleasing epic with jokes and fight scenes and eye-popping special effects. There’s no sense of preciousness; compared with American blockbusters, I find less fanservice here, less of an attempt to demonstrate ‘respect’ for the characters. One can argue whether Chinese or American blockbusters are more standardised — which hews more closely to an established structure, to a predefined vocabulary of plot twist and character development and banter. I can say only for myself that of the summer epics I’ve seen in the last few years, quite aside from the question of which I’ve enjoyed or which I think are better movies, on the whole the Chinese ones feel more free, and are more different one from another. I’ve seen three movies from the last few years involving Sun Wu Kong in a major role (four counting the two Donnie Yen movies separately), and they each have a different tone and do different things with the character. This movie’s the one that entertained me the most, the one that best captured the feel of a thrill-ride, the one that felt most dramatic. It tries to entertain; it succeeds.

From Wu Kong I headed across the street to see House of the Disappeared. This was directed by Dae-wung Lim from a script by Jae-hyun Jang based on Alejandro Hidalgo’s 2013 The House at the End of Time, Venezuela’s first horror film. As I noted above, I saw The House at the End of Time at the 2014 Fantasia Festival; it’s a magical-realist film with horror overtones and a horror atmosphere. I was surprised by the idea of taking the story and transposing it to South Korea, and wanted to see the result. In the end, I was surprised by how natural the result felt. I don’t think the remake is as good as the original, but it’s worth watching in its own right.

The opening begins much as in Hidalgo’s film: 25 years ago, a woman named Kang Mi-hee (Yunjin Kim) is living through a night of horror. We come in halfway through. We see her stumbling through her house, see her husband Cheol-joong (Jae-yoon Jo) die from a terrible wound, and see her son Hyo-je (Sang-hoon Park) abducted by a mysterious supernatural force. In the aftermath, Mi-hee’s arrested and convicted for the murder of her family. Twenty-five years later, she gets out of prison and returns to the house where it all took place. Strange things soon start happening. Is she in danger? And what really happened on that night twenty-five years ago? Flashbacks mingle with Mi-hee’s story in the present day and the attempts of a priest named Choi (Taec-yeon Ok) to help her.

The opening begins much as in Hidalgo’s film: 25 years ago, a woman named Kang Mi-hee (Yunjin Kim) is living through a night of horror. We come in halfway through. We see her stumbling through her house, see her husband Cheol-joong (Jae-yoon Jo) die from a terrible wound, and see her son Hyo-je (Sang-hoon Park) abducted by a mysterious supernatural force. In the aftermath, Mi-hee’s arrested and convicted for the murder of her family. Twenty-five years later, she gets out of prison and returns to the house where it all took place. Strange things soon start happening. Is she in danger? And what really happened on that night twenty-five years ago? Flashbacks mingle with Mi-hee’s story in the present day and the attempts of a priest named Choi (Taec-yeon Ok) to help her.

It’s a solid horror story, well-paced, with few gratuitous jump scares. Lim lets the mystery build, emphasising the horror we can see developing in the past. We know what will happen, but how do we get there? And how will that process inform Mi-hee in the present? The movie does a nice job of building up Mi-hee as a character while also keeping us at a bit of a distance from her in the present-day scenes. We don’t entirely know what she’s going through until near the end. By which point we’ve been drawn in by the family dynamics.

House of the Disappeared does a good job of telling a family-oriented horror story — not so much a horror story for the whole family (though given the minimal amount of gore I should think it’d be suitable for a relatively wide age range), as a horror story about a family. About a family going wrong, and about horrors specific to the experience of being in a family. Hyo-je is Mi-hee’s son from an earlier marriage; he has a half-brother who is Cheol-joong’s son, we learn, and we see the tensions this causes between Mi-hee and Cheol-joong and how the latter in particular treats the boys differently. And then how this refracts into tension between mother and father. You can see why Mi-hee married Cheol-joong, a strong-willed cop, and see why it’s a mistake and how flawed he is and how those flaws tie in to what makes him succeed at his job.

It’s difficult for me not to compare this movie to the original, if only for the contrast. Both are effective pieces of filmmaking; I think House of the Disappeared is more limited, but that’s more a function of being perhaps too willing to play by genre rules. The House at the End of Time was horrific, but also clearly magical realist, and one can argue that the final resolution felt in some ways science-fictional. House of the Disappeared keeps a straight horror focus while telling substantially the same story. The sense of wrongness common to horror stories persists almost all the way through the film. Surprisingly, it is in some ways a more emotional movie, as that horrific tension pays off by (to me) giving more weight to the family dynamics. The House at the End of Time, in my recollection years later, was dominated by Dulce, the matriarchal counterpart to Mi-hee. Mi-hee’s still very much the lead in House of the Disappeared, but I felt a greater involvement in her family — not just in the way the characters were developed, but in the depiction of the web of relations between them.

It’s difficult for me not to compare this movie to the original, if only for the contrast. Both are effective pieces of filmmaking; I think House of the Disappeared is more limited, but that’s more a function of being perhaps too willing to play by genre rules. The House at the End of Time was horrific, but also clearly magical realist, and one can argue that the final resolution felt in some ways science-fictional. House of the Disappeared keeps a straight horror focus while telling substantially the same story. The sense of wrongness common to horror stories persists almost all the way through the film. Surprisingly, it is in some ways a more emotional movie, as that horrific tension pays off by (to me) giving more weight to the family dynamics. The House at the End of Time, in my recollection years later, was dominated by Dulce, the matriarchal counterpart to Mi-hee. Mi-hee’s still very much the lead in House of the Disappeared, but I felt a greater involvement in her family — not just in the way the characters were developed, but in the depiction of the web of relations between them.

Visually, the atmosphere’s different in a fascinating way. Both films necessarily revolve around place: around the houses where the horrific supernatural events occur. The House at the End of Time gives us a house that’s dark, almost claustrophobic, with tight stairways and small rooms and perplexing corridors. House of the Disappeared gives us a much more open house, a lighter place enclosing larger spaces. It’s a little surprising to me that this makes for the more horrific film, but there it is: the contrast is greater. If the architecture of The House at the End of Time suggests age and complexity, there are many ways that complexity could pay off dramatically. There’s a kind of simplicity to the House of the Disappeared that’s all the more unnerving when the supernatural intrudes. The tension between the everyday and the impossible is more disconcerting.

If House of the Disappeared follows its original closely, it also throws in a few twists (in the form of new apparitions within the house) that don’t add up to much. Among the new elements are a revised origin for the house, which here turns out to have been built during the Japanese occupation by a Japanese general in collaboration with a wicked shaman. In character terms, Mi-hee and Dulce are very similar, but Cheol-joong is rather different from Dulce’s husband — more responsible in some ways, with a job giving him a higher status in society, but as much or more of an authoritarian, as much of an oppressive presence in the lives of his wife and stepson.

If House of the Disappeared follows its original closely, it also throws in a few twists (in the form of new apparitions within the house) that don’t add up to much. Among the new elements are a revised origin for the house, which here turns out to have been built during the Japanese occupation by a Japanese general in collaboration with a wicked shaman. In character terms, Mi-hee and Dulce are very similar, but Cheol-joong is rather different from Dulce’s husband — more responsible in some ways, with a job giving him a higher status in society, but as much or more of an authoritarian, as much of an oppressive presence in the lives of his wife and stepson.

These things perhaps have some relevance to the distinct natures of the cultures of Venezuela and Korea (I am not knowledgeable enough to say); but what’s intriguing is how much transfers easily from one to another. The general issue of the role of an older woman, obviously. But also the role of the Catholic Church: not only are the leading women in both films helped by priests in the present-day scenes, both have crucial scenes in the past in which the women have to go outside the Church to gain insight into their situations — a witch-like spirit medium in The House at the End of Time becomes a Korean shaman (recommended to Mi-hee by a feng shui geomancer) in House of the Disappeared. The genre shift, from magical realism to Korean horror, feels like a natural part of the translation process.

I would say that House of the Disappeared is a lesser film than The House at the End of Time. I think it sticks more closely to one genre, and while not more predictable on a plot level, is more emotionally predictable — you know what kind of terrain it’ll be covering. I felt it was photographed more conventionally; being brighter, I found it less textured. The age makeup wasn’t particularly convincing, though the acting was solid. Overall, it’s a solid horror movie with an unexpectedly bright ending. It’s worth turning to if you want a solid horror story, and worth watching if you’ve watched the original simply to see how the story works in a new context.

I would say that House of the Disappeared is a lesser film than The House at the End of Time. I think it sticks more closely to one genre, and while not more predictable on a plot level, is more emotionally predictable — you know what kind of terrain it’ll be covering. I felt it was photographed more conventionally; being brighter, I found it less textured. The age makeup wasn’t particularly convincing, though the acting was solid. Overall, it’s a solid horror movie with an unexpectedly bright ending. It’s worth turning to if you want a solid horror story, and worth watching if you’ve watched the original simply to see how the story works in a new context.

After the film screened, director Dae-woong Lim came out to take questions. Asked first about the genesis of the project, he said that the film’s producer discovered the original Venezuelan film, and suggested the remake project to him. Lim said that although he was a horror director he wouldn’t have agreed to the project if it was to be a generic horror film. He found himself, he said, drawn to the movie’s theme of motherhood.

He was asked about the spirits in the movie, and why there weren’t more of them (I’m being vague to avoid giving away plot points); he said that there might have been more, wandering around unseen. Asked whether the character of the younger brother was in the original, Lim said yes, it’s the same story, with the exception of the addition of the Japanese general to the house. He said that while doing the remake, he wanted to differentiate his movie by bringing in that new character. He also wanted to make sure the tone wasn’t too serious, and so added some comic relief. He wanted (according to my hand-scrawled notes) to make the movie more emotional, and to feel a Korean and Asian emotional texture.

Asked about a character who at one point reappears older than expected, Lim observed that he was asked the same question in Korea. He discussed the plot structure of the movie, and what happens when the doors in the house open; he reflected that he might have made the explanation easier to grasp. Asked about his inspirations, he mentioned Japanese and Korean horror films, as well as Dario Argento and Mario Bava. Asked if he himself was easily scared, Lim said he was: “That’s why I like horror movies.” The world in horror movies, he said, can’t be experienced in reality. Asked about working with actors, he said he enjoyed it. Asked about the process of casting, he said that his lead, Yunjin Kim, was famous in Korea, and was in a lot of American dramas (including Mistresses and Lost); he said she was very good at acting in a mystery-drama.

A member of the audience complimented him on the film, and said it echoed the kind of stories he was told as a child by his great-aunt; he asked Lim why he thought the story resonated so well with French-Canadian culture. Lim suggested it might be the work put into the original film from its director, Alejandro Hidalgo: “I think he was more excellent than me,” said Lim. (I suspect Lim’s right about the resonance coming from the original story; it strikes me that in addition to Quebec and Venezuela both being Latin cultures, the specific theme of the role of the Catholic Church has some resonance here as well.)

A member of the audience complimented him on the film, and said it echoed the kind of stories he was told as a child by his great-aunt; he asked Lim why he thought the story resonated so well with French-Canadian culture. Lim suggested it might be the work put into the original film from its director, Alejandro Hidalgo: “I think he was more excellent than me,” said Lim. (I suspect Lim’s right about the resonance coming from the original story; it strikes me that in addition to Quebec and Venezuela both being Latin cultures, the specific theme of the role of the Catholic Church has some resonance here as well.)

Asked how a woman in jail could keep her house, Lim pointed to some dialogue in the film establishing the house’s legal status, noting that houses owned by someone in jail could become ‘haunted houses,’ empty and not well-managed. Asked how Kim made the film more culturally Korean, he said that it came naturally from a Korean director and a Korean cast and crew making a movie for a Korean audience. The film reflected his identity and interest in Korean culture; it was a product of him. He was then asked if he heard any difference in the way a North American audience reacted to the film, and whether anything seemed to have been missed. He said that audience reactions were similar in Montreal and in Korea; people laughed and were startled at the same places. There was a minor plot point that might have been missed, he observed, which was also often missed by Koreans. (Without giving too much away, a character from a sort of flashback scene appears in scenes set later.) Finally, asked what his next project was, Lim said he was preparing a movie involving an airplane, in which the lead character wakes up to find everyone else aboard dead.

And that was my day at Fantasia. I had the next two days off, to attend to various errands, and then what looked like one of the more intriguing movies of the festival, before the weekend would bring a cavalcade of films.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.