Fantasia 2017, Day 5: Prisons, Rituals, and Explosions (The Honor Farm, Shock Wave, and Free and Easy)

Sunday, July 16, felt in some ways like the day Fantasia 2017 really began for me. I had three movies I planned to watch, of three very different kinds, though all at the De Sève Theatre. The first was a horror-inflected American independent film called The Honor Farm. The second was a Hong Kong action movie called Shock Wave (Chaak Daan Juen Ga). The third was a Chinese art movie called Free and Easy (Qīng sōng yú kuài). That mix of approaches, genres, and countries was characteristic of the festival. I looked forward to each movie individually, and to how they’d work together.

Sunday, July 16, felt in some ways like the day Fantasia 2017 really began for me. I had three movies I planned to watch, of three very different kinds, though all at the De Sève Theatre. The first was a horror-inflected American independent film called The Honor Farm. The second was a Hong Kong action movie called Shock Wave (Chaak Daan Juen Ga). The third was a Chinese art movie called Free and Easy (Qīng sōng yú kuài). That mix of approaches, genres, and countries was characteristic of the festival. I looked forward to each movie individually, and to how they’d work together.

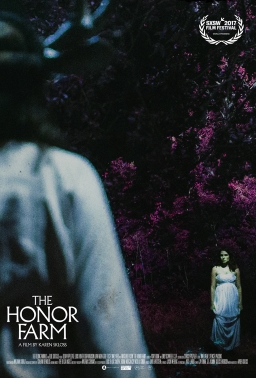

The Honor Farm was directed by Karen Skloss from a script written by Skloss with Jay Tonne Jr. and Jasmine Skloss Harrison — Skloss’ teen daughter. It’s the story of Lucy (Olivia Grace Applegate), who’s about to attend her senior prom and plans to lose her virginity with her boyfriend Jake (Will Brittain). It is, Lucy reflects, “the night I was finally free to do whatever I wanted. And everyone was expecting me to.” But things don’t go as she’d hoped. The date goes sour, and Lucy ends up hanging around with her best friend Annie (Katie Folger). They run into another group of teens led by the gothy Laila (Dora Madison Burge), who’re planning to go into a deep forest and take mushrooms provided by a group of boys led by the presumably-symbolically-named JD (Louis Hunter). There’s an abandoned prison close by they plan to investigate, the Honor Farm of the title. What will they find in the supposedly haunted building?

Nighttime, woods, hallucinating teens, an abandoned building, ghost stories: this sounds like a certain kind of horror movie, but in fact isn’t that at all. The Honor Farm owes very little to Wes Craven, and much more to John Hughes and David Lynch. That’s an odd pair of influences, and yet I found them inescapable: structurally the story’s about a weird mixture of teens with nothing in common who learn to be friends, while the story itself is built out of surrealism, dream-imagery, disorienting sounds and cuts, and extended sequences that might have happened and might only be hallucinations. Surprisingly, the two things balance each other very well. The arc of the story gives a clear framework for the stylish eruptions of the unreal.

Movies about teenagers trying to lose their virginity aren’t exactly uncommon, but most of them revolve around males, most are comedies, and most are exploitative. The Honor Farm is different from all of those, also, except that one can argue it’s a comedy in a strict formal sense: a story that ends well. Northrop Frye’s written about the green world of Shakespearean comedy — stories in which characters retreat to the woods, where as outcasts they find or make a better, truer society that ultimately reinvigorates the larger everyday world. There’s some of that here, which is to say that this is a movie whose story has deep and even elemental roots. John Clute in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy wrote about night journeys, harrowing experiences through which a story’s protagonist must pass to gain deeper wisdom or solve a problem; and so here Lucy goes through an initiatory night journey of her own, finding a symbolic ritual to mark her passage into adulthood. She, and the other teens, have left school. As the closing shots of the film show, they’re setting out into another world.

Movies about teenagers trying to lose their virginity aren’t exactly uncommon, but most of them revolve around males, most are comedies, and most are exploitative. The Honor Farm is different from all of those, also, except that one can argue it’s a comedy in a strict formal sense: a story that ends well. Northrop Frye’s written about the green world of Shakespearean comedy — stories in which characters retreat to the woods, where as outcasts they find or make a better, truer society that ultimately reinvigorates the larger everyday world. There’s some of that here, which is to say that this is a movie whose story has deep and even elemental roots. John Clute in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy wrote about night journeys, harrowing experiences through which a story’s protagonist must pass to gain deeper wisdom or solve a problem; and so here Lucy goes through an initiatory night journey of her own, finding a symbolic ritual to mark her passage into adulthood. She, and the other teens, have left school. As the closing shots of the film show, they’re setting out into another world.

This works because the sense of ritual and archetype grows out of character and out of a credible if impressionistic depiction of everyday life. Lucy and Annie and the other teens are established as real people with their own relationships and beliefs and attitudes, not through expository dialogue but through fragments of speech and sharp editing and good acting and clever costume choices — after Annie has to change her clothes early on, Lucy’s the only character in the film in a prom dress, a visual marker of her hopes and her situation. Following Lucy and Annie makes the other girls strange when we first meet them; and yet their getting in the car with them and driving away to a vague location in the wood feels right. It feels like the daring, stupid things people do as teenagers. The night ride is the sort of moment I suspect many people have, a moment that feels out of control, that feels like an adventure, even if the outcomes are likely to be worse than better and hopefully minor rather than major.

Well before she gets in the car, Lucy has asked herself “Why do I think so much?” The trip to the Honor Farm is her attempt to find an answer, to get away from thought. Fly from the conscious mind, though, and you end up mired in the subconscious. So it is here. She has also asked: “How do you know if something is real? When you wake up, how do you know you’re not still dreaming?” That’s prompted by the opening shots of the film, images which look like a flashforward, but turn out to be a dream sequence in a dentist’s chair. Those images recur, though, as does the dentist, all of them folded up and swallowed by another perceptual approach. In the woods, Lucy will be asked a riddle with an obvious answer — what has no beginning, end, or middle? In this context, that’s a reference to time: time past and time present both present in time future and time future contained in time past. In this movie they are all eternally present, but not unredeemable.

Well before she gets in the car, Lucy has asked herself “Why do I think so much?” The trip to the Honor Farm is her attempt to find an answer, to get away from thought. Fly from the conscious mind, though, and you end up mired in the subconscious. So it is here. She has also asked: “How do you know if something is real? When you wake up, how do you know you’re not still dreaming?” That’s prompted by the opening shots of the film, images which look like a flashforward, but turn out to be a dream sequence in a dentist’s chair. Those images recur, though, as does the dentist, all of them folded up and swallowed by another perceptual approach. In the woods, Lucy will be asked a riddle with an obvious answer — what has no beginning, end, or middle? In this context, that’s a reference to time: time past and time present both present in time future and time future contained in time past. In this movie they are all eternally present, but not unredeemable.

Still, if nothing ends, as the film implies, what then is the meaning of initiatory rituals? What do they mark, if not the progression from one state into another? Perhaps only the entrance into another phase of the round of life; as we see the full moon, a perfect circle, but a circle that wanes and waxes. An archetypal female image, too, so perhaps a fitting symbol for Lucy’s journey into the dream-world of sex and death. There are other dream-symbols used here, of course, and the film’s at its most Lynchian in the whimsy with which it chooses those symbols; the way it answers the portentous riddle about beginning, end, and middle, or the way in which Lucy’s dentist returns.

The prison itself is a symbol, a symbol of the dangers the teens face and of what they must journey through in order to escape. In a sense this is a movie about liberation, about freedom from institutions: about the kids finding a rite to mark the fact that they’re no longer kids in the eyes of society. The prison, now abandoned, is a social institution like the high school that they now must abandon. One of the boys explicitly points out that the school prom is a ritual; for all these teens (all white, it may be worth pointing out), the socially-sanctioned ritual of the prom is insufficient. They have to find a more powerful rite to mark their passage to adulthood, and that means creating a rite for themselves, much as Laila creates her own rite to speak to the dead. This is a film about free spirits creating a rite precisely in order to free their spirits.

The prison itself is a symbol, a symbol of the dangers the teens face and of what they must journey through in order to escape. In a sense this is a movie about liberation, about freedom from institutions: about the kids finding a rite to mark the fact that they’re no longer kids in the eyes of society. The prison, now abandoned, is a social institution like the high school that they now must abandon. One of the boys explicitly points out that the school prom is a ritual; for all these teens (all white, it may be worth pointing out), the socially-sanctioned ritual of the prom is insufficient. They have to find a more powerful rite to mark their passage to adulthood, and that means creating a rite for themselves, much as Laila creates her own rite to speak to the dead. This is a film about free spirits creating a rite precisely in order to free their spirits.

On a practical level, Skloss is able to create some highly effective imagery out of relatively low-tech tools. The hallucinations feel like hallucinations, not because of computer wizardry, but because of the eerie juxtaposition of things that could not naturally co-exist. At the same time, the cinematography’s excellent, creating atmosphere and a sense of place inside the crumbling prison and out: the woods feel deep and powerful, while also feeling like a connected series of locations, each with its own meaning.

The Honor Farm is a tremendously effective piece of filmmaking. It ends not with an overliteral dramatic revelation, but with the appropriate sense of a rite completed. That’s a little trickier to make work than it sounds. The film plays about with the idea that there are no endings, which is thematically fine but practically untrue: this is a film that does end, after a tight 75 minutes. Still, the conclusion’s nicely judged, and the film feels pivotal for all its brevity. It’s a powerful piece of work.

The Honor Farm is a tremendously effective piece of filmmaking. It ends not with an overliteral dramatic revelation, but with the appropriate sense of a rite completed. That’s a little trickier to make work than it sounds. The film plays about with the idea that there are no endings, which is thematically fine but practically untrue: this is a film that does end, after a tight 75 minutes. Still, the conclusion’s nicely judged, and the film feels pivotal for all its brevity. It’s a powerful piece of work.

After a bit of time to eat, I was back in the De Sève for my second movie of the day: Shock Wave, directed by Herman Yau from a script he wrote with Erica Li. Veteran action star Andy Lau is Cheung, a former undercover cop turned demolitions expert in Hong Kong. When a group of criminals take over one of the busiest underwater tunnels in the city and rig it with explosives, holding dozens of people in the tunnel hostage, Cheung and his men have to snap into action. But leading the criminals is Cheung’s old enemy Peng (Jiang Wu), who has plans for Cheung. And who’s the mastermind behind Peng?

Shock Wave is a competent, professional production that shows us exactly what a 1980s action movie looks like when it’s made in 2017. There’s relatively little fiddling about with cell phones and the internet. Instead we get a steadily intensifying plot that goes out of its way to give its hero and its villain personal stakes in the violence it depicts. When Cheung gets a girlfriend, Carmen (Song Jia, also at Fantasia this year in The Final Master), early in the movie, we know she’s going to spend a certain amount of the next two hours in danger; amusingly, she knows it too, breaking up with the heroic Cheung because, as she says, girls in super-hero movies don’t have good luck. It’s a nice try. Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t work, but it’s a nicely self-aware moment.

Shock Wave is a competent, professional production that shows us exactly what a 1980s action movie looks like when it’s made in 2017. There’s relatively little fiddling about with cell phones and the internet. Instead we get a steadily intensifying plot that goes out of its way to give its hero and its villain personal stakes in the violence it depicts. When Cheung gets a girlfriend, Carmen (Song Jia, also at Fantasia this year in The Final Master), early in the movie, we know she’s going to spend a certain amount of the next two hours in danger; amusingly, she knows it too, breaking up with the heroic Cheung because, as she says, girls in super-hero movies don’t have good luck. It’s a nice try. Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t work, but it’s a nicely self-aware moment.

The movie as a whole is self-aware enough that it never becomes “Die Hard in a tunnel.” In any event, the tunnel in this case is effectively an underwater tube; there’s no way to sneak around in it. Instead it becomes a claustrophobic location in which the villains squat with their hostages, roadblocks that have to be broken up. Much of the action in fact takes place outside the tunnel, as Cheung and his men try to find ways to defeat them, try to capture baddies who make a break for it, try to find out who’s behind the whole scheme.

That last subplot is perhaps unnecessary, but does serve to tie off the story with a flourish. And one can argue that it’s logical enough; without going into details, a major tunnel is a key part of a society and an economy, so to imagine a story like this one is almost inherently to make a comment about society. It’s not a terribly sophisticated comment, in this case, but it does feel like it’s tying in as many parts of the city as possible. Conversely, a subplot about off-duty cops among the hostages works better dramatically but doesn’t open up the story as much.

And the way the movie shows a lot of Hong Kong is notable. The slickly-shot film has a number of breathtaking views of the city at night, as police draw in to the tunnel entrances. English words turn up in the flow of Cantonese, a distinctive mix of language. It’s all an effective way to create a sense of scale; it’s not just that bad guys have taken over a tunnel, it’s that the tunnel is an important part of the life of a city, and the city isn’t just any city but this city that we see and hear. It’s not in any way groundbreaking, but it’s a solid way to heighten suspense by establishing a particular location.

In terms of performances, Lau does a solid job, charismatic yet credible. There’s a certain smile Cheung has early on when he talks about high explosives that gives the sense of a man who takes his job seriously but lightly; one suspects the same is true of Lau, who has dozens of movies in his filmography ranging from House of Flying Daggers to Infernal Affairs to Railroad Tigers to playing the voice of a rhino in The Little Penguin Pororo’s Racing Adventure (the man has range). Cheung’s a heroic cop surrounded by serious if not-quite-as-heroic men, and this is a story in which good and bad are clearly delineated, in solid action-movie terms.

In terms of performances, Lau does a solid job, charismatic yet credible. There’s a certain smile Cheung has early on when he talks about high explosives that gives the sense of a man who takes his job seriously but lightly; one suspects the same is true of Lau, who has dozens of movies in his filmography ranging from House of Flying Daggers to Infernal Affairs to Railroad Tigers to playing the voice of a rhino in The Little Penguin Pororo’s Racing Adventure (the man has range). Cheung’s a heroic cop surrounded by serious if not-quite-as-heroic men, and this is a story in which good and bad are clearly delineated, in solid action-movie terms.

In fact, Cheung’s heroism is anything but subtle. At one point he retells the fable of the mice who want to bell the cat; in his telling, a heroic mouse volunteers to put the bell on the cat and sacrifice himself if needed for the greater good. It’s an amusing way to establish his system of values. It’s also solid foreshadowing for an ending that reaches for a kind of operatic drama, and it gives the movie enough of a theme to be satisfying. It’s not subtle, but there’s at least a vague sense that it’s about something.

Whereas in fact the movie is fundamentally about action. That’s the bread and butter of this film: the rituals of the action movie. It’s well-staged and well-shot, as you might expect. Scenes play out in relatively unexpected ways, and end where you don’t always expect them to. Occasionally one wonders whether there perhaps ought to have been more police snipers at either end of the tunnel. And there are so many bad guys in the gang that none of them beyond Peng really become distinct even in visual terms, instead remaining generic gun-toting evildoers to be mowed down as and when appropriate. As well, one might wonder, as the siege drags on, how many hostages require food or medication or even simply to go to the bathroom — but then, one doubts that the bad guys would care much about any of that (they are gun-toting evildoers, after all).

Shock Wave is a movie that’s entirely competent at what it wants to do, at gunplay and suspense and explosions. It’s nicely varied, with the use of police procedural elements and various subplots, but always keeps its narrative centred and on track. It doesn’t reinvent the wheel, and doesn’t even try. It knows what it is, and knows what it’s doing. If a good solid action movie is what you want, then you will be satisfied here.

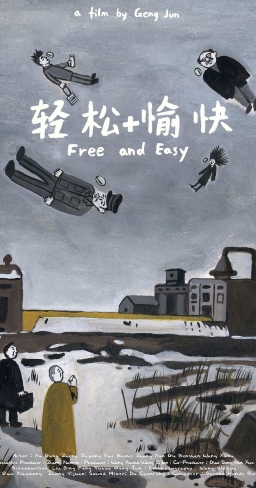

That brought me to my third movie of the day: Free and Easy, directed by Geng Jun, who co-wrote the script with Liu Bing and Feng Yuhua. It’s a crime story, in a way, about a number of con-men and small-time crooks who come together in a decaying industrial town in northern China; and in part about the cops who occasionally stir to take action. Not necessarily action directly related to their jobs, but some kind of action.

That brought me to my third movie of the day: Free and Easy, directed by Geng Jun, who co-wrote the script with Liu Bing and Feng Yuhua. It’s a crime story, in a way, about a number of con-men and small-time crooks who come together in a decaying industrial town in northern China; and in part about the cops who occasionally stir to take action. Not necessarily action directly related to their jobs, but some kind of action.

Still, even to say this is to risk giving a false impression. This is a movie built mainly of anecdotes, not structured around a strong central plot. Things build, but almost in the background. It loosely follows a black-coated middle-aged man, Zhang Zhiyong Zhang (played by a man named Zhang Zhiyong; though frequent collaborators with Geng, none of the actors here are professionals), who passes himself off as a soap salesman. His lime-green soaps have a special gimmick, though, which he uses to rob people blind. Among the other characters he interacts with are a devout Christian seeking his vanished mother (Gu Benbin Gu), a supposed Buddhist selling holy relics from a burned monastery (Xu Gang), a hard-bitten landlady (Wang Xuxu) who rents the soap salesman a room, and her husband (Xue Baohe) who’s desperately trying to figure out what’s happened to one of his roadside trees.

Not all of these plots pay off, not the way you’d expect them to. The movie’s built out of the way these people interact, testing each other and tricking each other and exploiting each other and, very occasionally, finding common ground. It’s a slow, laconic film, but exquisitely well-judged. The pacing’s just right to encourage meditation on what we’re seeing and draw out the undercurrents of a scene. At 98 minutes, this works well without feeling overly indulgent.

The pacing also lets us drink in the scenery. The depiction of the dying town’s hard and clear as the bright winter days that fill the screen: still frames and deep focus let us see every bit of crumbling mortar and decaying brick, all the empty spaces slowly going to ruin and slowly being reclaimed by a nature as equivocal and laconic as everything else in this movie. There’s no green here, or only in the flaking green walls inside the characterless houses, only in the magic soap that’s a con man’s tool. Dinginess is the characteristic of the city, a place where people used to live and form a society, a place now where people only scrabble out an atomised existence in the ruin of what used to be a community.

But if the place has decayed, it’s still maybe possible to reach out to others across whatever old industrial poisons affect body and mind. To me the theme of the movie is the balance of betrayals and coming-togethers, finding relations among people that move beyond con artist and mark. It’s not done easily and not something that happens without backsliding and underhanded games. But the conclusion of the movie seems to mark some point of connection, a web of characters uniting, however briefly. In a way, perhaps, the criminals’ ability to compromise lets them work with others; principles, religious or otherwise, become an obstacle to living with other people whose principles may not match.

There’s an oddball perspective on life in this movie, but one that’s often very funny. The amateur cast underplay nicely, letting humour emerge naturalistically from their actions. Which isn’t to say the film always aims at the comedic. But the langour of the pacing brings out a self-satirising edge to most scenes. Zhang Zhiyong’s flat stare challenges everything, weighing how serious things really are.

There’s an oddball perspective on life in this movie, but one that’s often very funny. The amateur cast underplay nicely, letting humour emerge naturalistically from their actions. Which isn’t to say the film always aims at the comedic. But the langour of the pacing brings out a self-satirising edge to most scenes. Zhang Zhiyong’s flat stare challenges everything, weighing how serious things really are.

That’s a useful approach for a character in an environment of constant low-scale criminality. There’s a sense in which the film’s depicting sordidness without wallowing in it. It’s lawlessness without either glamour or (much) brutality. Mostly this is a series of encounters between characters sounding each other out. In this context, it’s normal for attempts to interest the cops in criminal activity to bear no fruit; but then it’s also a context in which attempts to build friendships stand out. If it’s not a typical genre piece, neither is it realism in any traditional sense.

There’s an exquisite visual sense to Free and Easy. The shots are framed in distinctive ways, showing only half a conversation or presenting a background without commentary. The climax in particular has gunplay and characters running back and forth in a way quite unlike what that sounds like, and indeed not much like any other scene I can think of. It’s comic and tense at once, and if that ultimately comes from the script, it’s realised through strong shot selection.

The desolation of the scene’s so complete you hardly notice that there aren’t any signs of the 21st century. No cell phones, no mention of the internet. The police have a computer with a CRT screen. Are they behind the times, or is this a period piece? It perhaps doesn’t matter. The internet’s a foreign technology to this world, this small self-contained place where any kind of connection’s haphazard and deceptive if not dangerous. The logic of the story makes the internet irrelevant.

The desolation of the scene’s so complete you hardly notice that there aren’t any signs of the 21st century. No cell phones, no mention of the internet. The police have a computer with a CRT screen. Are they behind the times, or is this a period piece? It perhaps doesn’t matter. The internet’s a foreign technology to this world, this small self-contained place where any kind of connection’s haphazard and deceptive if not dangerous. The logic of the story makes the internet irrelevant.

Aurally as well as visually this is a desolation; the echoes of a man banging a gong, walking the streets for no clear reason, resonates in the crisp winter air. Fallen snow is untouched. The tone of the movie veers into the absurd, but although it’s consciously comedic it’s the opposite of zany. It’s an anti-genre genre piece, using bits and bobs of gangster films to give itself a bit of structure, a bit of tone. Its heart is somewhere else, not so much with the characters as with what the characters reveal. It’s satisfying, in the end, but — and indeed because — it demands a lot of its audience.

That wrapped up the day. Three movies of three different kinds. The next day I was looking at another three movies, equally different. Fantasia was in full swing, and it was pleasant to know that I had no real idea what lay ahead.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.