Fantasia 2017, Day 4: Urban Spaces (The Final Master and Tokyo Ghoul)

I had an odd schedule on Sunday, July 17. There were two movies I wanted to see. The first was a Chinese historical martial-arts film called The Final Master (Shi Fu), which played at noon. The second was a live-action Japanese manga adaptation, Tokyo Ghoul (Tôkyô gûru), and that played at 9:35 in the evening. I eventually decided to go to the Hall Theatre for the first movie, spend the afternoon doing errands, and return for the second movie in the evening. In the end, this turned out to be a good plan.

I had an odd schedule on Sunday, July 17. There were two movies I wanted to see. The first was a Chinese historical martial-arts film called The Final Master (Shi Fu), which played at noon. The second was a live-action Japanese manga adaptation, Tokyo Ghoul (Tôkyô gûru), and that played at 9:35 in the evening. I eventually decided to go to the Hall Theatre for the first movie, spend the afternoon doing errands, and return for the second movie in the evening. In the end, this turned out to be a good plan.

The Final Master was written and directed by Haofeng Xu, based on his original novel. It follows Chen Shi (Fan Liao), a martial-arts master, who arrives in the city of Tianjin in 1932. He wants to establish a school there of his own but faces opposition from the major schools already in the city. He has to overcome a series of challenges from his scheming rivals, political as well as physical. He begins a romance with Zhao Guohui (Jia Song, also at Fantasia this year in the Hong Kong action film Shock Wave), a beautiful woman with a scandal behind her, and begins training a rickshaw driver named Geng (Yang Song, who was also in both of Xu’s previous movies, Judge Archer and The Sword Identity) who may have even more talent for fighting than Chen himself. But if Geng may help him overcome some of the trials set by the other schools, yet other levels of politics come into play as the military plans a takeover of the martial-arts world.

This really only scratches the surface of the intricate film. There’s a novelistic feel to it in the accumulation of incident and character, but it’s remarkably effective because Xu keeps things moving at a rapid if not unforgiving pace. Plans are hatched, betrayals accumulate, and the scope of the film increases bit by bit. It’s not quite an epic, but characters who seem minor develop into major figures, and the city of Tianjin acquires a character of its own.

As a director Xu’s known for his focus on realism over wire-work, and on his interest in the codes of honour of the martial-arts of the past. I saw his Judge Archer last year, and there’s a similar seriousness of tone here — though the storytelling in this movie strikes me as more straightforward, allowing for a more complex plot. This is a film with a lot on its mind, about the past, about honour, about culture, and about the way in which the transition to the modern world affected all these things.

As a director Xu’s known for his focus on realism over wire-work, and on his interest in the codes of honour of the martial-arts of the past. I saw his Judge Archer last year, and there’s a similar seriousness of tone here — though the storytelling in this movie strikes me as more straightforward, allowing for a more complex plot. This is a film with a lot on its mind, about the past, about honour, about culture, and about the way in which the transition to the modern world affected all these things.

On the one hand, the film seems to want to evoke a bygone world of noble masters decaying into the corrupt present day. On the other hand, it’s far too smart to indulge in that kind of romanticisation of the past. The masters of Tianjin aren’t wise sages. They may be clever, but they make mistakes and compromises. “His kung fu is terrible, but his money is good,” one of Chen’s friends says of a highly-placed student; this cheerful cynicism turns out to be a mistake. Betrayal’s never far away in this movie, and small, seemingly harmless weaknesses can bring down anyone.

Chen himself is an honourable man caught in changing times. What’s the worth of kung fu skills in a world run on money? Not much, in his case; rather more, in the case of the big schools of Tianjin. The movie’s careful handling of class and wealth make a nice counterpoint to the drama of the martial-arts world. It’s not as simple as saying that Chen’s just and poor. As much as anyone in the film, he makes some terrible choices. He wants to pass on his skills, and he must struggle to do that — even as the whole world he knows is shifting underneath him.

There’s a finality implied in the title, one we can sense all the way through the movie. The movie’s occasionally funny — one fight scene, in which Chen and Zhao discuss their pasts, is hilarious — but there’s a sense of doom brooding over the whole story. Here as elsewhere Xu balances elements nicely, driving toward an inevitable violent conclusion but finding ways to leaven the grimness with charm.

There’s a finality implied in the title, one we can sense all the way through the movie. The movie’s occasionally funny — one fight scene, in which Chen and Zhao discuss their pasts, is hilarious — but there’s a sense of doom brooding over the whole story. Here as elsewhere Xu balances elements nicely, driving toward an inevitable violent conclusion but finding ways to leaven the grimness with charm.

I’ve come this far without mentioning the action sequences; the film has enough depth it’s almost easy to forget it’s nominally a kung-fu movie. In fact, there are long stretches without fighting, or with only a few training sequences. But when the fights do come, particularly in the violent climax, they’re extremely well-shot. There’s a precision and a terrible clarity to the movements and the editing, a sense of realism; a lot of the fights are over quickly. If the relative lack of fighting fits with the theme of omnipresent political maneuvering, then the nature of the fights shows the reality of martial-arts in Tianjin: fights in which multiple enemies attack at once, rather than decorously engaging in a series of single combats; fights in which masters take advantage of wounded or weakened opponents.

This is an intelligent movie, one that dextrously builds a complex plot and complex characters in the service of a larger theme. It is also somewhat self-aware: film intersects with martial-arts in two key moments of the story. On the one hand, both have to do with terrible betrayals of good masters. On the other hand, one of the set-pieces near the end of the film is based around a presentation of The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple (Huo shao hong lian si), one of the great early successes of the Chinese film industry, and a movie that set the template for martial-arts movies to follow. Or so I’ve heard. The actual film has not survived to the present, and so perhaps here it’s a symbol of what is lost in the conflicts of the various martial-arts schools. New technology, movies and trains and guns, bring new things of value. But even those things can be lost in a moment.

This wouldn’t come across as well, I think, if The Final Master weren’t as effective as it is in evoking a time and place. The film feels austere, bright and yet grey, but also feels built of wood and stone. Tianjin is a character, as I said, and that’s because in this movie it’s a place at a specific time, with people whose lives fit into history and who are shaped by the technologies and political realities around them.

This wouldn’t come across as well, I think, if The Final Master weren’t as effective as it is in evoking a time and place. The film feels austere, bright and yet grey, but also feels built of wood and stone. Tianjin is a character, as I said, and that’s because in this movie it’s a place at a specific time, with people whose lives fit into history and who are shaped by the technologies and political realities around them.

It’s not flawless. The balancing of incidents sometimes seems to distract from the main plot, especially around the middle of the film. Character is well-drawn, but often feels flat — if remarkably rich for any other martial-arts film. The actors underplay, which mostly works, but in conjunction with the slight flatness of the script creates some oddly emotionless moments. Conversely, some moments feel emotionally overwrought; a long walk by a wounded man in particular feels like a melodramatic touch. And it is difficult to draw a convincing line between a realistic evocation of the martial-arts scene and the melodrama of kung-fu challenges.

Still, if The Final Master isn’t quite the Watchmen of kung-fu films, it’s fairly close to being the genre’s Unforgiven. It’s aware of the limitations of the violence it shows, aware that history isn’t as clean and idealistic as much of its genre would wish. It knows that good guys don’t always win, and you can’t trust redemptive violence to end injustice. But it also knows that there’s a power in the idea of all those things, and knows that good men (and women) can be caught up in those ideals and be led into all sorts of strange places. It’s the thinking viewer’s martial-arts film, and I would say a progression from Judge Archer. Remarkably, it hints at yet greater things to come from Xu.

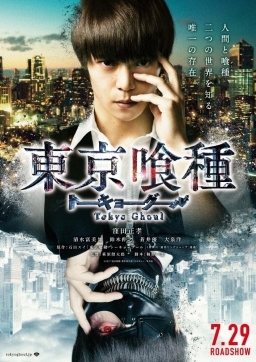

So a good start to Sunday. In the evening, errands accomplished, I returned as planned for Tokyo Ghoul. Worth noting that before the film began, there was a moment of silence for George Romero, who had died the day before.

Tokyo Ghoul was directed by Kentaro Hagiwara from a script by Ichiro Kusuno based on Sui Ishida’s best-selling manga. The manga’s spawned a sequel and prequel, and has also been adapted into an anime. Set in a world where humans co-exist with a predator species called ghouls, humanlike creatures who eat human flesh, it follows Ken Kaneki (Masataka Kubota) whose infatuation with a beautiful woman leads him to an unfortunate encounter with a ghoul — which in turn leads to him becoming part-ghoul himself. This has never happened before, and Kaneki has to try to understand what’s happening to him as he navigates a new world of monsters and of humans determined to destroy all monsters.

Tokyo Ghoul was directed by Kentaro Hagiwara from a script by Ichiro Kusuno based on Sui Ishida’s best-selling manga. The manga’s spawned a sequel and prequel, and has also been adapted into an anime. Set in a world where humans co-exist with a predator species called ghouls, humanlike creatures who eat human flesh, it follows Ken Kaneki (Masataka Kubota) whose infatuation with a beautiful woman leads him to an unfortunate encounter with a ghoul — which in turn leads to him becoming part-ghoul himself. This has never happened before, and Kaneki has to try to understand what’s happening to him as he navigates a new world of monsters and of humans determined to destroy all monsters.

This is a surprisingly clever film. The opening few minutes suggest it’ll be a broad, knowing B-horror movie. And then it cuts a bit deeper into Kaneki’s confusion and terror. And then things get worse for him; and then at about the halfway point everything changes, as Kaneki finds not all ghouls are vicious or entirely without remorse. I don’t think it gives too much away to say that after a first half that emphasises the horror elements of the story, Kaneki finds a kind of surrogate family of ghouls and the story’s genre shifts to something like a kind of YA tale of heroes and villains. Human agents who wield terrible weapons emerge as a threat to Kaneki, his adopted family, and the possibility Kaneki represents of reconciliation between humans and ghouls.

This ought to go off the rails at some point, but it never really does. The sly humour of the opening minutes could have gone wrong, and yet it doesn’t. The weakness of the shambolic plot, in which Kaneki becomes a monster through an incredibly unlikely series of coincidences, is nodded at and then left behind; his origin is a kind of necessary evil, and somehow you don’t mind too much, somehow it makes sense. As a character, Kaneki and his confusion and fear are strong enough and broad enough that it’s easy to get on board with the story.

In fact, the first half of the film gives us a kind of degeneration and rebuilding of Kaneki, as he must explore more and more of his new monstrous aspects, and naturally reacts with fear and disgust to what’s become of him. There’s some body horror here — ghouls have the ability to manifest weapons from their flesh, each ghoul with a different power — but less than one might imagine. If a number of scenes revolve around the eating of meat, including human meat, it works as a kind of gleeful reminder of what we’re actually watching. The grossness comes home to us. And yet we aren’t repulsed from Kaneki. We learn with him what’s happened to him, and what he can now do.

In fact, the first half of the film gives us a kind of degeneration and rebuilding of Kaneki, as he must explore more and more of his new monstrous aspects, and naturally reacts with fear and disgust to what’s become of him. There’s some body horror here — ghouls have the ability to manifest weapons from their flesh, each ghoul with a different power — but less than one might imagine. If a number of scenes revolve around the eating of meat, including human meat, it works as a kind of gleeful reminder of what we’re actually watching. The grossness comes home to us. And yet we aren’t repulsed from Kaneki. We learn with him what’s happened to him, and what he can now do.

Possibly as a result, the genre shift feels natural. It’s set up well, paying off plot elements introduced earlier; but more than that, it feels as though the horror-story aspect has played itself out by the time the YA-story kicks into gear. We’ve followed Kaneki as far as that genre can take us. The next step is up into a different kind of story.

There’s a considerable amount of blood in the film, which never really goes away for too long. There’s a lot of darkness and of lurid colour, and that never entirely goes away either. It’s reminiscent of the Parasyte movies in its general feel of monsters hiding in shadowed urban spaces, and in the professional sheen of its photography and story structure; but it’s much more graphic, aimed at a somewhat older audience.

I enjoyed Tokyo Ghoul more than I expected. It’s a movie that’s simply better than it had to be. The twists in the story are solid, the worldbuilding is solid, the staging of the fights is solid. The acting communicates what we need to know about the characters, who are broad but also distinctive. The CGI has some cartoony moments, but then also some quite elegant images as well. The human government agents who emerge as antagonists are well-developed enough that they feel like major threats, even though they’re outnumbered and theoretically out-powered.

Does it have much to say? No and yes. There’s much talk about sin and morality in the movie, in a non-religion-specific way. I found that over-broad, and not entirely convincing. More intriguing to me were hints about the importance of letting the past go and moving on from hatred and one’s old life. One character tells another: “Let your past haunt you. It’s what makes us strong.” But these are villains. Kaneki survives by letting go his humanity — but only in part. It’s an interesting balancing act.

Does it have much to say? No and yes. There’s much talk about sin and morality in the movie, in a non-religion-specific way. I found that over-broad, and not entirely convincing. More intriguing to me were hints about the importance of letting the past go and moving on from hatred and one’s old life. One character tells another: “Let your past haunt you. It’s what makes us strong.” But these are villains. Kaneki survives by letting go his humanity — but only in part. It’s an interesting balancing act.

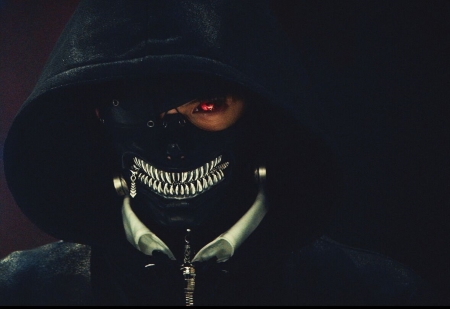

If Tokyo Ghoul works, and I feel it very much does, that’s in part because it handles its genre elements so deftly, diving deep into the world it’s imagined without losing touch with its characters. The genre elements feel natural even as they build, in other words, and are credible even as Kaneki goes from a lone victim to an inductee into a new society. Some aspects of that society never quite emerge the way you might think they would; ghouls have special war-masks, for example, which never quite become the visual motif they could have. The world perhaps could have been even richer, in terms of the details of ghoul life and ghoul society — but the film knows what it wants to focus on, and how, and it’s hard to argue with its choices.

The movie ends nicely, feeling like it’s reached a real conclusion without foreclosing the possibility of a sequel. It’s a nice piece of work, a good sturdy genre vehicle that tells its tale and does a fine job of it. It hits what it aims at, which is all you can ask for. If you want a YA-inflected urban fantasy that doesn’t skimp on horror and blood, here you are, with some nice fight scenes into the bargain.

The movie ends nicely, feeling like it’s reached a real conclusion without foreclosing the possibility of a sequel. It’s a nice piece of work, a good sturdy genre vehicle that tells its tale and does a fine job of it. It hits what it aims at, which is all you can ask for. If you want a YA-inflected urban fantasy that doesn’t skimp on horror and blood, here you are, with some nice fight scenes into the bargain.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.