Fantasia 2017, Day 3, Part 1: Cinematic Anthologies (SpectrumFest: Films from the Autism Spectrum and The International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase 2017)

Saturday, July 15, looked like an unusual day for me at Fantasia: I’d mostly be seeing short films. It’d begin a bit after noon, with a set of shorts called SpectrumFest: Films from the Autism Spectrum, a collection of pieces from young filmmakers on the autism spectrum. Then would come this year’s edition of the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase, featuring eight science-fictional short films from around the world. Both showings looked fascinating, if in different ways. SpectrumFest was new to me, but I’d seen the SF showcases in previous years, and been impressed both by the individual films and by the way they worked together — if short films are loosely equivalent to prose short stories, the SF short film showcases make excellent anthologies.

Saturday, July 15, looked like an unusual day for me at Fantasia: I’d mostly be seeing short films. It’d begin a bit after noon, with a set of shorts called SpectrumFest: Films from the Autism Spectrum, a collection of pieces from young filmmakers on the autism spectrum. Then would come this year’s edition of the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase, featuring eight science-fictional short films from around the world. Both showings looked fascinating, if in different ways. SpectrumFest was new to me, but I’d seen the SF showcases in previous years, and been impressed both by the individual films and by the way they worked together — if short films are loosely equivalent to prose short stories, the SF short film showcases make excellent anthologies.

First came SpectrumFest. Montreal’s Spectrum Productions is a non-profit organization who works with youth and young adults on the autism spectrum, giving them resources and equipment to express themselves creatively through film and animation. Among other programs, Spectrum runs summer camps and a weekly after-school program, as well as Saturday morning cartoon-making workshops. This year, Fantasia hosted an exhibition of some of the films created by the young filmmakers working with Spectrum in a showcase that was free to the public. Almost two dozen of the student filmmakers’ productions were screened, collectively a stunning and unpredictable burst of creativity.

I want to at least mention each of the films that played, as part of the effect of the showcase was the dizzying range of techniques and approaches. First was “Music Through the Mouth,” by Anthony Campoli, a film in which voice and video samples are mixed into an original rhythmic piece of music accompanied by animation; a second “Music Through the Mouth” piece would come later in the showcase, with more elaborate instrumentation. Both pieces are catchy and visually effective. Max Lachapelle’s brief (54-second) animated “A Day in Minecraft” effectively mixes Minecraft visuals with another cartoon pop-culture character. William Mitchell’s “Beethoven Octopus” is wonderfully surreal animation depicting the title character (with the upper body of Ludwig van Beethoven and the lower body of an octopus) struggling against the nefarious plans of his archenemy, Bach Squid. “Aaron is Cool,” by Aaron Itzkovitz, is a fast-paced 43-second list of cool things. Mathieu Dutaud’s “2 Stupid Dogs” mixes live-action elements into an animated comedy about the increasing chaos caused by the title characters.

I want to at least mention each of the films that played, as part of the effect of the showcase was the dizzying range of techniques and approaches. First was “Music Through the Mouth,” by Anthony Campoli, a film in which voice and video samples are mixed into an original rhythmic piece of music accompanied by animation; a second “Music Through the Mouth” piece would come later in the showcase, with more elaborate instrumentation. Both pieces are catchy and visually effective. Max Lachapelle’s brief (54-second) animated “A Day in Minecraft” effectively mixes Minecraft visuals with another cartoon pop-culture character. William Mitchell’s “Beethoven Octopus” is wonderfully surreal animation depicting the title character (with the upper body of Ludwig van Beethoven and the lower body of an octopus) struggling against the nefarious plans of his archenemy, Bach Squid. “Aaron is Cool,” by Aaron Itzkovitz, is a fast-paced 43-second list of cool things. Mathieu Dutaud’s “2 Stupid Dogs” mixes live-action elements into an animated comedy about the increasing chaos caused by the title characters.

“Trouble in the Astral Plane,” by Tristan Therien-Roussel, follows a man experimenting with meditation and out-of-body experiences as a way to take vacations; things don’t go as he expects, and the resulting story mixes a clever use of technique with an unpredictable stream-of-consciousness structure. Leo Clark’s “Basketball Rivalry” is a five-minute-plus short that transposes the structure of a kung fu movie onto a basketball court. “Michael Sings Whatever He Wants,” by Michael Geurreri, is a charming take on infomercials for record albums. Marco Macri’s “Pac Man” is a brief (21 seconds) animated take on the famous arcade character. Aiden Holmes’ “Meme Quest Ultimate” is a great energetic shoot-em-up in which a group of teens seek the dankest of dank memes in a building built on a dank graveyard.

Robin Mahar had two films, “Vacuum Man” and “Vacuum Man 2.0,” in which we follow an unusual cyborg superhero about his daily life and see him rebuilt. Jordan Astles’ “Lego Peter’s Kitchen Disaster” is a stop-motion movie with lego, mosnters, and explosions. “Zunder’s Origin,” by Phillipe Hoss-Gagnon, is an epic fantasy under four minutes long, in which one member of a family group of demigods gains the power to defeat a diabolical villain. “Badtoons Invasion,” from Lucas Leroy, is another story of invasion, this one animated, in which evil toons attack a peaceful land. Ani Morrow follows a group of “Floating Heads” as they float up a hill and discuss the good and bad aspects of bodies. “Owen the Sea Cowboy,” from Owen McDonough, follows the title character, the lead of a nature show, as he goes to the Bay of Fundy and rides a blue whale. Brendan Mirajello-Giglio’s “Papersons Episode 2” follows a hero trying to defend an animated universe from an invasion by erasers; fortunately he gets advice from “the most obscure scientist in all of Montreal.”

Robin Mahar had two films, “Vacuum Man” and “Vacuum Man 2.0,” in which we follow an unusual cyborg superhero about his daily life and see him rebuilt. Jordan Astles’ “Lego Peter’s Kitchen Disaster” is a stop-motion movie with lego, mosnters, and explosions. “Zunder’s Origin,” by Phillipe Hoss-Gagnon, is an epic fantasy under four minutes long, in which one member of a family group of demigods gains the power to defeat a diabolical villain. “Badtoons Invasion,” from Lucas Leroy, is another story of invasion, this one animated, in which evil toons attack a peaceful land. Ani Morrow follows a group of “Floating Heads” as they float up a hill and discuss the good and bad aspects of bodies. “Owen the Sea Cowboy,” from Owen McDonough, follows the title character, the lead of a nature show, as he goes to the Bay of Fundy and rides a blue whale. Brendan Mirajello-Giglio’s “Papersons Episode 2” follows a hero trying to defend an animated universe from an invasion by erasers; fortunately he gets advice from “the most obscure scientist in all of Montreal.”

In David Riverin’s “Pizza Hypnotics” the winner of a pizza-eating contest eats so much pizza he travels to another dimension. Kevin Eugenio’s “The Kenners 3: Stars in Heaven” was one of the longest pieces in the showcase, at over 16 minutes; shot in black-and-white, it’s the story of a man trying to deal with his more successful elder brothers. It has some effective jokes, and an unexpected twist ending. “Garfield Can’t Mind His Own Business,” from Nathanial Palermo, is a series of quick animated gags using the comic-strip cat. “Alien 3,” from Austin Roach, sees an unusual spaceship crew fight and flee a monster. Michael Geurreri’s “Milkies” is an enjoyable stream-of-consciousness story set around a kidnapped Donald Trump (“we thought he was inconsiderate,” the kidnappers claim). The showcase ended with Sam Clarke and Jordan Astles’ 16-minute “New Age of Heroes,” in which a team of superhero teens has to come together to defeat an invading alien. Classic genre tropes are given new spins in an energetic story that climaxes with a special-effects battle royale.

Add it all up, and it was an exhilarating ride. I don’t know enough about autism to look for, or speak to, any distinctive characteristics in the films pertaining to the condition. What I can say is that there was an incredible amount of sheer imagination on display, and a considerable grasp of narrative structure. There was a constant kind of high-energy surrealism that worked to tell stories. Relative to other student films I’ve seen, it seemed to me that very often sound was especially well-used. I also thought that the many animated pieces were smooth and visually engaging, often integrating live-action elements particularly well.

Add it all up, and it was an exhilarating ride. I don’t know enough about autism to look for, or speak to, any distinctive characteristics in the films pertaining to the condition. What I can say is that there was an incredible amount of sheer imagination on display, and a considerable grasp of narrative structure. There was a constant kind of high-energy surrealism that worked to tell stories. Relative to other student films I’ve seen, it seemed to me that very often sound was especially well-used. I also thought that the many animated pieces were smooth and visually engaging, often integrating live-action elements particularly well.

After the showcase, some of the filmmakers came out for a brief question-and-answer session, along with two of the adults from Spectrum Productions (Liam O’Rourke, one of the founders, and Eric Bent, animator). According to my hand-scrawled notes, the first question was about the favourite genres of the directors; Tristan Therien-Roussel said his favourite was action, while another filmmaker, Jordan Astles (I believe) preferred stop-motion animation. Someone asked where Spectrum Productions was based, and was told they had a studio in Montreal’s Mile End neighbourhood. Asked how the organization got started, O’Rourke said that while working with autistic students in the school system, one had the idea of making a short. That became a pilot film camp that ran for a week. Spectrum developed from there, and now runs 11 weeks with a year-round program as well.

Asked about their future plans, Therien-Roussel said he would keep on adding videos to his YouTube channel (I can’t find that channel, but here’s the channel for Spectrum Productions). One of the other directors, Anthony Campoli, said he was about to start in Concordia University’s Film and Animation program. Asked what started them into films and how they came to Spectrum, Therien-Roussel said he was inspired by a game, while Campoli said his aunt suggested the program to him. Robin Mahar, creator of “Vacuum Man,” said that he created the movies because he loves Dyson vacuum cleaners. Astles talked about his plans for the team in “New Age of Heroes,” detailing an elaborate plot for a future film — which led O’Rourke to note that a Spectrum Cinematic Universe was developing, with the young filmmakers planning crossovers and making references to each others’ work.

Asked about their future plans, Therien-Roussel said he would keep on adding videos to his YouTube channel (I can’t find that channel, but here’s the channel for Spectrum Productions). One of the other directors, Anthony Campoli, said he was about to start in Concordia University’s Film and Animation program. Asked what started them into films and how they came to Spectrum, Therien-Roussel said he was inspired by a game, while Campoli said his aunt suggested the program to him. Robin Mahar, creator of “Vacuum Man,” said that he created the movies because he loves Dyson vacuum cleaners. Astles talked about his plans for the team in “New Age of Heroes,” detailing an elaborate plot for a future film — which led O’Rourke to note that a Spectrum Cinematic Universe was developing, with the young filmmakers planning crossovers and making references to each others’ work.

That ended SpectrumFest. Next came my second short film showcase of the day, this time the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase 2017. This year Fantasia’s annual collection of SF shorts boasted eight films from five countries. Having seen some remarkable works of cinema in previous years, I was eager to see what 2017 would bring.

The first short was an American humor piece called “Swell,” directed by Bridget Savage Cole (I can’t find writing credits online). In the near future, a smartphone app has the ability to change your mood through sound, with increasingly comic results for one couple (Britt Lower and Gabriel Luna) whose apps get set to produce different feelings. It’s a well-structured and well-paced piece, building nicely as the app creates different emotions and mindsets. The comedy’s got some point, too; Lower’s Ana is a songwriter who goes through different phases of inspiration and self-doubt as a function of the app. Cole shoots the film in bright, pastel colours that seem to echo the colour schemes currently favoured for app design, and it feels rich without distracting from the actors — whose ability to play different emotions and switch emotions at the drop of a hat carry the movie.

“Hum,” from the UK, came next. Written and directed by Stefano Nurra, it’s based around the real phenomena of mysterious hums or other noises audible to certain people in specific places. This story follows Chris Page (Adam Shaw), a plumber approaching middle age, who begins hearing a very loud and agonising noise at odd times. Trying to understand what’s happening to him, he finds Professor James McAven (James Bryce), a disgraced professor who specialised in quantum physics. McAven’s theories point to an explanation of the hum, but McAven himself may have ulterior motives for what he tells Chris.

“Hum,” from the UK, came next. Written and directed by Stefano Nurra, it’s based around the real phenomena of mysterious hums or other noises audible to certain people in specific places. This story follows Chris Page (Adam Shaw), a plumber approaching middle age, who begins hearing a very loud and agonising noise at odd times. Trying to understand what’s happening to him, he finds Professor James McAven (James Bryce), a disgraced professor who specialised in quantum physics. McAven’s theories point to an explanation of the hum, but McAven himself may have ulterior motives for what he tells Chris.

“Hum” strikes me as primarily a character piece shaped by some intensely science-fictional ideas about the intersection of multiple realities. It avoids any kind of standard heroic sensibility; Shaw’s Chris is afflicted, not chosen, while Bryce’s McAven is an obsessive who provides an explanation for the film’s novum but is the opposite of a wise mentor. The film’s shot with an eye for realism, for the dimness of a pub or the closeness of a bathroom where Chris works. As you might expect, the sound design’s key, using the absence of noise as effectively as the high-pitched ringing from which Chris suffers. In the end, the mystery of the hum sets up a deeply personal dramatic resolution; but also feels like an idea which cries out for more examination. It’s an effective story, in that the characters make important choices that define who they are, and it’s an effective science-fiction story, in that those choices are based around the non-mimetic concepts underpinning the story. If those concepts are profound enough that they could be explored at length in any number of different ways, still there’s no doubt “Hum” maintains its focus, does what it wants to do, and tells a very solid tale.

I’ll also note here that in the question-and-answer period after the showcase, Nurra was asked about science-fictional inspirations for “Hum,” to which he replied that the movie was strongly influenced by the New Weird, especially China Miéville. He also noted that it’s hard to find New Weird stories on film. A day or two after, I’d have a conversation with him and producer Scott Imren; Imren felt that the lack of exposure to the New Weird made it difficult to explain the film to people who hadn’t seen it — as of yet, the common reference points don’t exist for people in cinema. They have (as I understand it; my notes are sadly lacking) developed the concept of “Hum” to a full feature film, and are shopping it around. I bring all this up mainly to note that the New Weird angle does come through in the short, though it struck me as more of a Jeff VanderMeer Weird than Miéville. On the other hand, one could say that rather than the baroque Weird of Bas-lag, this is the this-world Weird of The City & the City. And either way a Miéville-like awareness of class is present, if mostly as a rich subtext.

I’ll also note here that in the question-and-answer period after the showcase, Nurra was asked about science-fictional inspirations for “Hum,” to which he replied that the movie was strongly influenced by the New Weird, especially China Miéville. He also noted that it’s hard to find New Weird stories on film. A day or two after, I’d have a conversation with him and producer Scott Imren; Imren felt that the lack of exposure to the New Weird made it difficult to explain the film to people who hadn’t seen it — as of yet, the common reference points don’t exist for people in cinema. They have (as I understand it; my notes are sadly lacking) developed the concept of “Hum” to a full feature film, and are shopping it around. I bring all this up mainly to note that the New Weird angle does come through in the short, though it struck me as more of a Jeff VanderMeer Weird than Miéville. On the other hand, one could say that rather than the baroque Weird of Bas-lag, this is the this-world Weird of The City & the City. And either way a Miéville-like awareness of class is present, if mostly as a rich subtext.

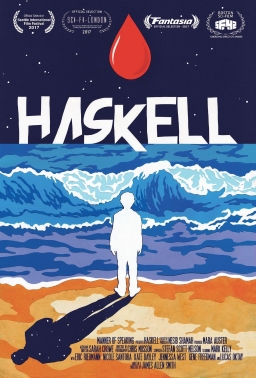

Next was another American film, “Haskell,” written and directed by James Allen Smith. The title character’s a man (Mark Kelly) born a few seconds out of step with time; we move between seeing him as a boy learning to control his sense of time and fit in with the world, as an adult facing a tense confrontation over a failed business, and also as an older man reflecting on his life. The cross-cutting between timelines works, and the inevitable twists that come with a time-travel story work as well. But this again is filmed in a largely realistic way, in terms of the lighting and settings and its concentration on the emotions undergirding the lines of the script; and so what stands out is Kelly’s remarkable performance as Haskell, sad and solemn and wise in a way that’s hard to define. There’s a warmth to him that makes the movie work. A lot goes on in 11 minutes, a lot to do with finding one’s place and finding one’s way out of places. While Smith’s script and visual sense are quite fine on their own — building a story around a set of conversations, around tight close-ups and precise editing — Kelly’s presence (and that of Lucas Oktay as the young Haskell) pulls it all together.

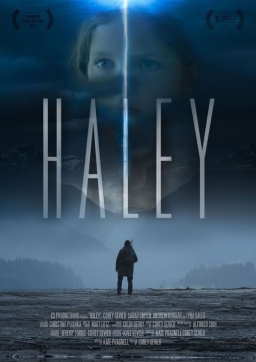

Following that came the Canadian short “Haley,” directed by Corey Sevier from a script by Kate Pragnell. Sevier also edited, produced and starred in the 21-minute film. We see first a man (Sevier) and his daughter, Haley (Lyra Sales), who flee an alien invasion; then, for most of the movie, we are in a wilderness, some time later, following a figure we soon recognise as the father. He interacts with other people fleeing the aliens. But he has a personal mission to fulfill, the accomplishing of which brings about a sharp climax and sudden ending.

Following that came the Canadian short “Haley,” directed by Corey Sevier from a script by Kate Pragnell. Sevier also edited, produced and starred in the 21-minute film. We see first a man (Sevier) and his daughter, Haley (Lyra Sales), who flee an alien invasion; then, for most of the movie, we are in a wilderness, some time later, following a figure we soon recognise as the father. He interacts with other people fleeing the aliens. But he has a personal mission to fulfill, the accomplishing of which brings about a sharp climax and sudden ending.

It struck me firstly as a nicely-shot film. The invaders are kept offscreen, but the chaos they bring is shown, and a clever special effect establishes what’s happening. Then, when the scene shifts to forests and mountains, the cinematography gives us a strong sense of atmosphere — foreboding shadows, flickering firelight, the sublimity of a mountain height. There’s a grimness in the way it’s shot that reflects the post-invasion world, and the sensibility of the main character. Plotwise, the film’s sparing with information, dislocating us, and adding an air of tension to the confrontations between characters: we don’t know exactly what’s going on, or what’s right, or who to believe. The ending’s nicely judged, clear, meaningful, and yet open to interpretation. This is a well-crafted story that finds an unexpected transcendence in nature and the science-fictional.

Another American short was next, “Miriam is Going to Mars,” written and directed by Michael Lippert. A woman named Miriam Johnson (Ann Sonneville) is hearing voices and has been institutionalised; when she sees a commercial soliciting would-be colonists to Mars, she concludes that the vacuum of space will hush the voices, and sends in a video response. Almost from the start you can tell that a happy ending is impossible. Miriam’s hoping for an escape, but there is at present no escape from her condition. The use of the putative Mars colony, apparently based on the Mars One program (something of a sad story in itself), gives the story a central image that it uses well enough. Sonneville is appropriately heartbreaking in her role, upbeat and optimistic about the idea of going into space, to the point where her final attempt to find an escape is believable. And yet I felt that the movie slightly misses its mark. Things are weighted too heavily against Miriam; as I said, there’s no doubt about the general way the movie will end, if not the specifics, while at the same time being too ambiguous to feel tragically predetermined. It’s almost excellent, but for me at least, it felt a little too pat.

After that was “The Sleepers,” another American movie, directed by Joe Lueben and written by Lueben with Trevor Tweeten. In the not-too-distant future, Sleep Centers hold patients, four to a room, who are kept in an artificial sleep for 23 hours a day, waking only briefly to eat and exercise. A reporter speaks with the four women who sleep in one such room, gathering their stories and learning why they came to choose to spend most of their lives asleep.

After that was “The Sleepers,” another American movie, directed by Joe Lueben and written by Lueben with Trevor Tweeten. In the not-too-distant future, Sleep Centers hold patients, four to a room, who are kept in an artificial sleep for 23 hours a day, waking only briefly to eat and exercise. A reporter speaks with the four women who sleep in one such room, gathering their stories and learning why they came to choose to spend most of their lives asleep.

The film mixes the stories of the sleepers, told in voice-over to the reporter, with images of their dreams. Unfortunately, the dreams aren’t especially memorable; I found a lack of dream-logic or vivid dream-imagery. The stories are simple enough, mostly revolving around love or lack of same. I’ll note that I’m not sure having the one black woman be a convict serving out her sentence is the best choice, though her dream does create some sense of an ending. Overall, I felt there are good moments to the movie, and it’s an interesting way to tell the stories of four different lives, but there’s a lack of narrative momentum, and the stories are in the end too similar.

Spain’s “Amo,” written and directed by Alex Gargot, followed. It’s about a man (Salvador Roman) and two robots he’s created in the shape of women. One, Mia, is a girl who serves him as a maid but has developed an unhealthy fixation upon him. The other, Domo, is in the shape of a mature woman, and is intended as for companionship. I could not find a way to make this film work for me. It’s shot well, and the sound design is rich. But I could not understand why one robot worked and one did not; nor how the “solution” ending the film is supposed to work; nor how the emotional landscape of Mia is supposed to make sense. The doctor’s relation to the two robots he’s made is uncomfortable to watch; one looks for echoes of Frankenstein, but I could find none. One looks for a challenge to the patriarchal structure of the household; again, I could find none. The conclusion can be interpreted a few ways, I suppose, ranging from the cynical to the appalling. For me, this was a well-crafted misfire.

Finally came “The Last Schnitzel,” a science-fiction satire directed by Kaan Arici and Ismet Kurtulus, from a script by Arici, Kurtulus, and Onur Koralp. It’s a Turkish-language film that was shot in Denmark, and ran into some issues when it was submitted to an Istanbul film festival; the Turkish Culture Ministry required significant cuts before they’d allow it to be played. The filmmakers refused to make the edits, instead pulling the film out of the festival. I can’t imagine what sort of cuts were required. This is a politically engaged film — it opens with a disclaimer noting that it’s fiction and any resemblance to persons living or dead is coincidence, then adds “but everyone is free to draw their own conclusions.”

Finally came “The Last Schnitzel,” a science-fiction satire directed by Kaan Arici and Ismet Kurtulus, from a script by Arici, Kurtulus, and Onur Koralp. It’s a Turkish-language film that was shot in Denmark, and ran into some issues when it was submitted to an Istanbul film festival; the Turkish Culture Ministry required significant cuts before they’d allow it to be played. The filmmakers refused to make the edits, instead pulling the film out of the festival. I can’t imagine what sort of cuts were required. This is a politically engaged film — it opens with a disclaimer noting that it’s fiction and any resemblance to persons living or dead is coincidence, then adds “but everyone is free to draw their own conclusions.”

It’s also a very funny movie. In the distant future, the Earth’s environment is collapsing, and the last humans on the planet are preparing to flee. Except for the Grand Turkish Republic, whose President (Haluk Bilginer) refuses to evacuate until he’s had one final terrestrial chicken schnitzel. Unfortunately, chickens went extinct 200 years before. His assistant, Kamil, must find a way to procure one last chicken schnitzel to save the people of Turkey. This sets up a satire of authoritarianism and politics with an almost classic structure: a man must perform an impossible task just to satisfy the absurd whim of an autocrat, with the aim of saving people the autocrat rules. Certainly Arici and Kurtulus are aware of their satirical predecessors (one fracas in a government chamber draws the cry “There is a situation in the situation room!”) and maneuver their story deftly to mock international relations, nepotism, and the arrogance of rulers. Of course the problem’s solved by the subversive wit of an apparent servant. How else?

Visually, the future’s appropriately dark, but also sleek, owing a little to some iterations of Star Trek. The effects are well-placed, and the worldbuilding in the background fits the tone of the movie nicely; I was reminded a little of Stanislaw Lem in a sardonic mood. Kamil’s developed as much as he needs to be, and you soon come to admire his resourcefulness — he thinks of a number of things to try, and it just so happens none of them work out until the last. The humour’s broad, but nevertheless clever, with a few subtle offhand touches (as in the Kubrick reference). It’s fast-paced, and however much it applies specifically to Turkish politics, its mockery of authoritarianism feels both of the moment and lasting.

After the shorts came a brief discussion with Stefano Nurra (director of “Hum”), James Allen Smith (director of “Haskell”), Joe Lueben (director of “The Sleepers”), and Nicholas Williams (producer of “The Sleepers”). Asked first what the origins of their various projects were, Smith, who had observed before the showcase began that he was a documentarian who decided he wanted to branch out to fiction, added that he’d always liked time travel and had once been a computer trader, which had led him to think about what he could do if he could project himself one second forward into the world — and how strange that would be. Nurra said that he’d stumbled on to the mystery of people who heard a strange noise and didn’t know where it came from. He said that he’d always wanted to represent other worlds, and visualise what is difficult to visualise. Lueben talked about struggling against depression, and how he had not wanted to get out of bed. He’d wondered if that could be socially acceptable. As well, he himself kept a dream journal.

After the shorts came a brief discussion with Stefano Nurra (director of “Hum”), James Allen Smith (director of “Haskell”), Joe Lueben (director of “The Sleepers”), and Nicholas Williams (producer of “The Sleepers”). Asked first what the origins of their various projects were, Smith, who had observed before the showcase began that he was a documentarian who decided he wanted to branch out to fiction, added that he’d always liked time travel and had once been a computer trader, which had led him to think about what he could do if he could project himself one second forward into the world — and how strange that would be. Nurra said that he’d stumbled on to the mystery of people who heard a strange noise and didn’t know where it came from. He said that he’d always wanted to represent other worlds, and visualise what is difficult to visualise. Lueben talked about struggling against depression, and how he had not wanted to get out of bed. He’d wondered if that could be socially acceptable. As well, he himself kept a dream journal.

Smith was asked about the casting in “Haskell,” and whether his experience as a documentarian had helped him. Smith agreed the acting was a massive part of the movie, and said that casting had been the most important part of the film. As a documentarian he hadn’t been on a real set before, instead making films as a “one-man-band.” Picking actors for the first time was scary. In the end, lead actor Mark Kelly never read for the part, but hung out with Smith for a few days talking over the character and his nature. Smith said that he tried to let the actors bring themselves to their parts, to do what he could beforehand and then in shooting let what happened happen.

The team from “The Sleepers” was asked about the striking design of the sleep chamber in their film. They said that the producer’s brother is a sculptor and artist, who created 3D models of the room, based around honeycombs as a design that maximised efficiency. They created the set based on the models, and Lueden spoke about seeing the set for the first time and knowing everyone else on the film had to up their game. He was impressed with how well the set worked with the lighting and other cues, how the space became a character.

The directors were then asked about their favourite films and directors. Lueden said that he hadn’t seen Tarkovsy’s Solaris when he finished a rough cut of the film; he finally saw it in response to comments on his own work. He also noted that he loved Kubrick. Nurra said he’d wanted to stay away from stylisation in “Hum,” creating a visual world that was dirty, grungy, and high-contrast. He said he was influenced by Aronofsky’s The Wrestler. Smith said he was influenced by Shane Carruth, obviously Primer, but also what Carruth was able to do in Upstream Color visually and emotionally on a tight budget. He also mentioned Timecrimes, by Nacho Vigalondo, and said that he found lo-fi science-fiction to be a major trend at the moment. Nurra was asked about his science-fictional inspiration (covered above), and that concluded the questions and the answers.

The directors were then asked about their favourite films and directors. Lueden said that he hadn’t seen Tarkovsy’s Solaris when he finished a rough cut of the film; he finally saw it in response to comments on his own work. He also noted that he loved Kubrick. Nurra said he’d wanted to stay away from stylisation in “Hum,” creating a visual world that was dirty, grungy, and high-contrast. He said he was influenced by Aronofsky’s The Wrestler. Smith said he was influenced by Shane Carruth, obviously Primer, but also what Carruth was able to do in Upstream Color visually and emotionally on a tight budget. He also mentioned Timecrimes, by Nacho Vigalondo, and said that he found lo-fi science-fiction to be a major trend at the moment. Nurra was asked about his science-fictional inspiration (covered above), and that concluded the questions and the answers.

I now had a break, enough time for a quick bite to eat. Then it would be back to Fantasia to see my first and only full-length feature film of the day.

I now had a break, enough time for a quick bite to eat. Then it would be back to Fantasia to see my first and only full-length feature film of the day.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.