Godzilla, So-So Solo-Act: The Return of Godzilla (Godzilla 1985)

The most recent Japanese Godzilla film, 2016’s Shin Godzilla (aka Godzilla: Resurgence), is about to stomp into North America on Blu-ray. Shin Godzilla received an extremely limited one-week run in U.S. theaters in October 2016 — the theater where I watched it ran it once each on Saturday and Sunday morning — so this home video release is the first opportunity most people in Region A will have to see it. (I’ve reached a point where I no longer consider the world in terms of nations but of Blu-ray region coding. “What part of the world are you from?” “Region A.”)

The most recent Japanese Godzilla film, 2016’s Shin Godzilla (aka Godzilla: Resurgence), is about to stomp into North America on Blu-ray. Shin Godzilla received an extremely limited one-week run in U.S. theaters in October 2016 — the theater where I watched it ran it once each on Saturday and Sunday morning — so this home video release is the first opportunity most people in Region A will have to see it. (I’ve reached a point where I no longer consider the world in terms of nations but of Blu-ray region coding. “What part of the world are you from?” “Region A.”)

As prep for examining Shin Godzilla, I’m warping back to 1984 and the film in the series with which it has the most in common, i.e. the last time Godzilla went solo, with no other monster in sight: The Return of Godzilla. The home video timing works out well, since The Return of Godzilla only recently had its own digital video debut in North America on a Blu-ray from Kraken Releasing. In fact, the film hasn’t been available here on home video in any format since the late 1990s.

It’s also the first time the original version of the film has been legally available in the United States. When The Return of Godzilla first reached American theaters, it was as a grotesque Dr. Pepper-fueled mutant hybrid called Godzilla 1985. This Americanized version has been heavily slagged for decades for good reasons, but the original isn’t a hidden gem like the Japanese version of King Kong vs. Godzilla. Don’t expect a kaiju epiphany on your first viewing of The Return of Godzilla.

The Reboot of Godzilla

Known in Japan simply as Gojira, The Return of Godzilla was a reboot of the series long before that term for franchise reimagination became popular. It ignited the “Heisei” series of Godzilla films that lasted until 1996 and brought the legendary monster to a second height of fame and quality. Which is strange, since The Return of Godzilla doesn’t look as if it could ignite anything bigger than a tealight candle.

After 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla flopped, the Godzilla series went into hibernation for nine years. Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka insisted it was temporary and Godzilla would eventually return, but Tanaka wanted a splashy and spectacular comeback. Years of development hell followed, and at one point it appeared a Hollywood version might get off the ground, Godzilla: King of the Monsters in 3-D. However, no American studio agreed to the budget the filmmakers proposed, and Tanaka finally got impatient and greenlit a domestic Godzilla film.

Although Tanaka got his wish for a larger, more expensive Godzilla movie dressed up as an “event” picture, The Return of Godzilla feels like something the filmmakers threw together at the last minute. Despite ambitious intentions to make Godzilla a symbol of 1980s Cold War nuclear brinksmanship, most of the talent behind and in front of the cameras couldn’t carry it off. There are a few solid performances, some well-done effects set-pieces, and a terrific score, but The Return of Godzilla is overly simplistic and banal. It’s amazing the action and comic-book thrills of the rest of the Heisei series rose up from such a stagnant pool. (For details on this era, read Part 4 of my History of Godzilla on Film.)

Although Tanaka got his wish for a larger, more expensive Godzilla movie dressed up as an “event” picture, The Return of Godzilla feels like something the filmmakers threw together at the last minute. Despite ambitious intentions to make Godzilla a symbol of 1980s Cold War nuclear brinksmanship, most of the talent behind and in front of the cameras couldn’t carry it off. There are a few solid performances, some well-done effects set-pieces, and a terrific score, but The Return of Godzilla is overly simplistic and banal. It’s amazing the action and comic-book thrills of the rest of the Heisei series rose up from such a stagnant pool. (For details on this era, read Part 4 of my History of Godzilla on Film.)

The Return of Godzilla is presented as a direct sequel to the 1954 Godzilla, skipping the other fourteen movies of the previous era (now called the Showa Series). But it’s also a remake of sorts, as the Japanese title indicates: it contains only a few references to the original movie and ignores that Godzilla perished at the bottom of Tokyo Bay at the climax, skeletonized by Dr. Serizawa’s oxygen destroyer. The Showa Series got around Godzilla’s death by introducing a second member of Godzilla’s species in the first sequel, Godzilla Raids Again (1955), and then never bringing up the subject again. The Return of Godzilla not only ignores the monster’s destruction in the 1954 original, it never mentions Dr. Serizawa or the oxygen destroyer. You’d think a pivotal focus for trying to stop a new Godzilla would be to duplicate the weapon that destroyed the first one. But The Return of Godzilla shrugs off this intriguing development. (The oxygen destroyer becomes pivotal in the last Heisei movie, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah, seeming to atone for this movie abandoning it.)

The Super-X, Scientists, and a Startlingly Effective Government Official

The screenplay by Shuichi Nagahara, who wrote Toho’s 1977 space opera The War in Space, follows the back-to-basics ideas Tanaka laid out in his plot sketch. Thirty years after Godzilla’s initial rampage, a Japanese fishing boat witnesses the radioactive monster’s re-emergence after a volcanic eruption, although only one man aboard survives the encounter. At first the Japanese government keeps Godzilla’s return a secret, but is forced to break their silence to prevent a confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union after Godzilla destroys a Soviet submarine. The Japanese Self-Defense Force plans to attack Godzilla with the Super-X, a flying weapons platform, while scientist Dr. Hayashida and his assistants develop an alternate plan. Godzilla comes ashore to rampage in Tokyo, some Cold War shenanigans interfere, Godzilla destroys the Super-X, the scientists pull off their plan, and Godzilla is temporarily disposed of.

The story of The Return of Godzilla is that simple, which is a contrast to the sometimes over-stuffed later Heisei movies. But simplicity isn’t an asset here. There just isn’t much happening: no counterplots, sudden revelations, military secrets, scientific surprises, or bizarre characters.

This scarcity of story is a bigger problem for a Godzilla film where there’s no other monster. A solo-Godzilla can only work once before the limitations of the kaiju genre kick in. Watching the military repeatedly engage Godzilla while scientists search for a way to stop it quickly turns tiresome. A second (or third, or fourth, or tenth) monster broadens story possibilities and gives the human characters more to do. It also relieves Godzilla of the burden of carrying all the action. The Big-G often works best with reduced screen time, coming in gradually until taking over for the final confrontation. (This is an aspect of the Toho movies that the 2014 Godzilla got perfect. So, of course, some viewers complained that “There wasn’t enough Godzilla!” in the movie. No, there is exactly the right amount of Godzilla.)

This scarcity of story is a bigger problem for a Godzilla film where there’s no other monster. A solo-Godzilla can only work once before the limitations of the kaiju genre kick in. Watching the military repeatedly engage Godzilla while scientists search for a way to stop it quickly turns tiresome. A second (or third, or fourth, or tenth) monster broadens story possibilities and gives the human characters more to do. It also relieves Godzilla of the burden of carrying all the action. The Big-G often works best with reduced screen time, coming in gradually until taking over for the final confrontation. (This is an aspect of the Toho movies that the 2014 Godzilla got perfect. So, of course, some viewers complained that “There wasn’t enough Godzilla!” in the movie. No, there is exactly the right amount of Godzilla.)

It’s not impossible to pull off a latter-day Godzilla solo act, but Tomoyuki Tanaka didn’t assemble a team with enough collected talent or time to meet the challenge. This is partially the fault of the Japanese film industry’s shrinkage from its creative and productive peak in the 1960s: there wasn’t the same massive talent pool to draw on.

The problems start at the top with director Koji Hashimoto, who was picked for the assignment because of his direction of another Toho science-fiction film, Sayonara Jupiter. Back in 1954, Tomoyuki Tanaka took a chance with director Ishiro Honda for Godzilla, and it paid off richly. Lightning didn’t strike twice: Hashimoto falls into a gray journeyman zone between the humanism and artistry of Ishiro Honda and the more action-schlocky fun of Jun Fukuda, the other major Godzilla director of the Showa Era. Hashimoto’s direction style keeps the dramatic scenes at TV movie level, with few camera set-ups and minimal blocking. Mostly, it’s people sitting and talking.

Hashimoto does get the film off to a promising start with his most energetic piece of direction, a horror-like opening aboard a fishing boat where a giant radioactive sea louse from Godzilla’s skin (Shockirus) has turned the crew into desiccated corpses. The three-foot-long Shockirus is about as close as we get to a second monster, but the scene of it attacking the reporter exploring the death ship is nasty and frightening. The sequence doesn’t jell with the rest of the film, and the Shockirus is rapidly forgotten (a few more should’ve appeared during Godzilla’s city attack, dropping onto the crowds as the monster passes), but it’s one of the only sprint moments in a movie that soon settles into a slow jog.

The cast adds little to their generic parts as “hero reporter,” “love interest,” and “the brother with vague sciency job.” Even veteran actor Yosuke Natsuki doesn’t elevate Dr. Hayashida, a part originally meant for Akihiko Hirata, who played Dr. Serizawa in Godzilla ‘54. Hirata died before filming started, and Natsuki (the lead in Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster) stepped in to play the elder scientist. But I doubt any actor could’ve brought much life to Dr. Hayashida as written and directed. Hayashida has no real conflict, even though his parents died in Godzilla’s initial rampage. He made peace with the monster long before the story starts. The absence of any personal conflict on the ground, even the most minor stereotypical kind (the “love story” hardly develops into the hand-holding stage), is a place where The Return of Godzilla misses a huge part of why the 1954 original succeeded.

The cast adds little to their generic parts as “hero reporter,” “love interest,” and “the brother with vague sciency job.” Even veteran actor Yosuke Natsuki doesn’t elevate Dr. Hayashida, a part originally meant for Akihiko Hirata, who played Dr. Serizawa in Godzilla ‘54. Hirata died before filming started, and Natsuki (the lead in Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster) stepped in to play the elder scientist. But I doubt any actor could’ve brought much life to Dr. Hayashida as written and directed. Hayashida has no real conflict, even though his parents died in Godzilla’s initial rampage. He made peace with the monster long before the story starts. The absence of any personal conflict on the ground, even the most minor stereotypical kind (the “love story” hardly develops into the hand-holding stage), is a place where The Return of Godzilla misses a huge part of why the 1954 original succeeded.

There’s one exception, however, and it comes from the most unexpected place: the government conference scenes. The figure of Prime Minister Mitamura (Keiju Kobayashi) is the standout role as the only character who appears to feel the burden of Godzilla’s return. As much as there is any gravity in The Return of Godzilla’s human scenes, it’s centered on him.

The prime minister’s key moment pits him against pressure from the world’s two superpowers, who want permission to use nuclear weapons against Godzilla. The prime minister informs the envoys that Japan will adhere to its Three Non-Nuclear Principles: the non-possession, non-production, and non-introduction of nuclear weaponry. When the Soviet and U.S. envoys respond that Japan is being egotistic and it isn’t the time to discuss principles, the PM ripostes:

It is precisely because things reached this point that I am adamant regarding this. There is no such thing as “safe” nuclear weaponry. What’s more, should we use them just once, it would destroy the balance of power that has made them a deterrent force. It would lead to the world’s end. That is the nature of nuclear weapons. If you would call Japan’s Three Non-Nuclear Principles “egotism,” then so be it. However, is not the Soviets’ and the Americans’ desire to use nuclear weapons also egotism?

This is the single place where a glimmer of the spirit of Ishiro Honda and the original Godzilla shines through, as well as the sense of hearing the voice of the only country to have suffered a nuclear attack. Immediately following the Prime Minister’s speech is a quiet scene where Mitamura explains to a few advisors how he appealed to the envoys in private, asking them to imagine if a nuclear weapon were used in Moscow or Washington, D.C. It’s a facile sentiment following the Three Non-Nuclear Principles speech, but Kobayashi plays it so well, trembling with the responsibility he has taken on, that it’s the most effective bit of drama in the film. If only the passion in these scenes wasn’t confined to them.

Perhaps there was no way to hold up this level of hard-hitting drama in an ‘80s Godzilla film. The 1954 movie captured a historical moment, and Godzilla as a multi-movie franchise survived afterward because it headed in different, often stranger directions. Yet it would’ve made for a better movie if The Return of Godzilla stretched a bit more to reach for weightier thoughts than, “Hey, Godzilla is destructive again!” and “Geopolitics is hard!”

The Next Era of Godzilla Effects

The Next Era of Godzilla Effects

Can the special effects salvage the movie? Not really, but that isn’t the fault of the effects team. The FX work is some of the best in any Godzilla film up to the time, although not the leap forward in technology it should’ve been considering the massive shift in effects work since 1975.

Between 1975 and 1984 the city of Tokyo enlarged at such a rate that Godzilla had to step up a bit. The Showa Era monster was 50 meters tall, which would leave Godzilla dwarfed by most of the city’s skyscrapers. Godzilla was pumped up to 80 meters, which required reducing the scale of all the miniatures and a subsequent loss of details. The model buildings still look good, but the miniature vehicles suffer a noticeable drop in realism. This may explain why there isn’t enough Godzilla vs. the Self-Defense Force action in the movie, leaving it to the Super-X to handle the big battle.

Godzilla is the best “effect” in the film. The redesign of the costume is fearsome and intimidating, although the large white eyes contrast too much with the rest of the look — something the next Godzilla costume would correct. A robotic head is used for some of the close-ups, which was created as part of a promotional full-sized animatronic Godzilla called the “Cybot.” The Cybot was never meant for film work, and it shows: the robotic head doesn’t match the look of the costume and it wobbles noticeably when moving.

But again, the effects themselves aren’t the problem. It’s the pacing of the VFX sequences, which don’t have enough room to breathe and build to thrilling climaxes. The scientists figure out how to stop Godzilla mid-way through the movie, which is in itself dramatically dull. But the method they use — tricking Godzilla with bird sounds to lure him into a volcano — is dopey and leads to a yawner of a close. The spectacle the film promises never happens.

The serious pace-killer is Godzilla taking a fifteen-minute nap in the middle of the rampage in Tokyo. The urban destruction is what we came to see, but after a couple of minutes of admittedly fun model-smashing, the Super-X shows up and hits Godzilla with cadmium shells that send the monster into a slumber. The next stretch of film is filled with the science heroes trying to escape from the top of a building and the accidental launch of a Soviet nuclear missile heading straight for Tokyo. In theory this should be thrilling (the missile launch, not the building escape) but like much of the film, it doesn’t work. The handling is so limp and compressed that there’s zero tension to it. You just want Godzilla to wake the hell up and get to crushing things again.

The serious pace-killer is Godzilla taking a fifteen-minute nap in the middle of the rampage in Tokyo. The urban destruction is what we came to see, but after a couple of minutes of admittedly fun model-smashing, the Super-X shows up and hits Godzilla with cadmium shells that send the monster into a slumber. The next stretch of film is filled with the science heroes trying to escape from the top of a building and the accidental launch of a Soviet nuclear missile heading straight for Tokyo. In theory this should be thrilling (the missile launch, not the building escape) but like much of the film, it doesn’t work. The handling is so limp and compressed that there’s zero tension to it. You just want Godzilla to wake the hell up and get to crushing things again.

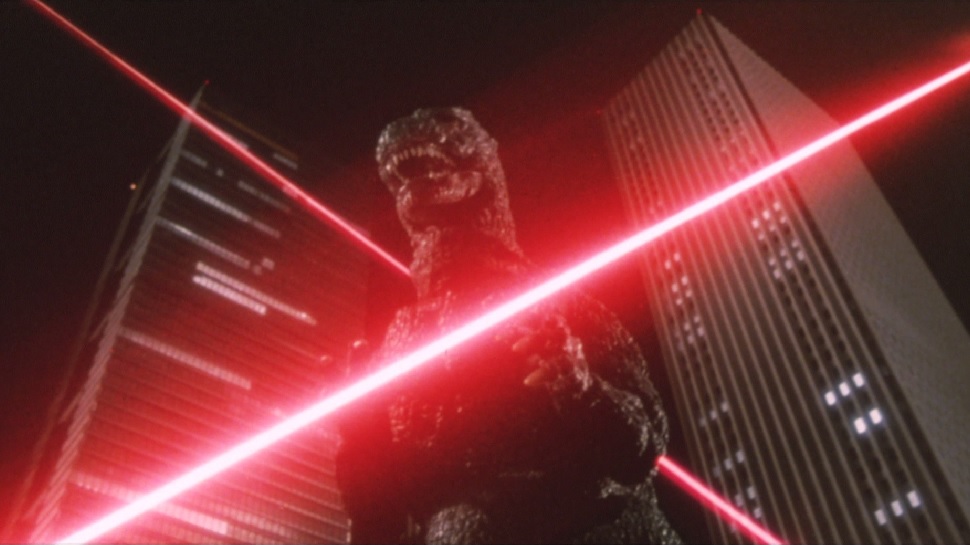

When Godzilla finally revives, we do get the movie’s best giant monster moment. Godzilla takes on the Super-X through a maze of Shinjuku skyscrapers. The Super-X spits out missiles and lasers in a desperate attempt to slow down the monster. The Super-X finally runs out of power, leading to the moment when Godzilla gets to do what it does best: ludicrous overkill! Godzilla doesn’t stomp the Super-X or roast it with a radioactive ray. Godzilla dumps an entire friggin’ skyscraper onto it, giving human technology a big kaiju middle finger. The movie either needed more of this or more of the prime minister being overly grave. Falling in the middle and not even executing that well simply doesn’t pass muster with what’s supposed to be Godzilla’s big comeback.

There are a few other special effects moments that stand out. Godzilla’s first full emergence is the right type of slow unveiling: a towering POV shot moving through fog toward a nuclear power plant, followed by a pan up the monster’s body. The 2014 Godzilla used an almost exact duplicate of this shot for its first reveal. Godzilla’s initial engagement with the Self-Defense Force in Tokyo Bay, although too brief, does feature a spectacular climax when Godzilla sweeps a radioactive ray across the entire defense frontline and roasts it to cinders. Overkill, Godzilla needs more overkill!

Godzilla 1985 — Wouldn’t You Like to Be a Pepper Too?

New World Pictures, a low-budget production company formerly owned by Roger Corman, picked up the US rights to The Return of Godzilla … which they then chewed up and spat out as Godzilla 1985. It’s understandable why a US distributor would tamper with an already shaky product that had little chance of surviving at the North American box office. But New World was all thumbs and no cash when it came to the execution.

Trying to imitate the transformation job that turned 1954’s Godzilla into 1956’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters!, New World hired Raymond Burr to repeat his role of reporter Steve Martin (now addressed as “Mr. Martin” for obvious reasons) in newly shot scenes from the point of view of the United States. But there’s no effort to make these scenes mesh with the Japanese footage; it’s simply Raymond Burr and a few military officials hanging out in a small set remotely watching Godzilla’s destruction while drinking Dr. Pepper. Burr doesn’t phone it in — he took the role and Godzilla seriously — but the rest of the footage is played for cheap jokes with a military officer (Travis Swords) dredged up from the depths of Comedy Relief Hell making terrible wisecracks as Tokyo burns. He also drinks Dr. Pepper. Did I mention Dr. Pepper put up some money for this? Because Dr. Pepper put up some money for this.

Most notoriously, New World’s executives forced changes to the storyline to make the Soviets into the villains. Instead of accidentally firing a missile from their space platform, the Soviets now launch the missile on purpose. It’s obnoxious and undercuts one of the better aspects of the original: the position of Japan between two evenly balanced super powers. Also undercutting this is the removal of most of the prime minister’s scenes, taking away the film’s best dramatic moments.

Most notoriously, New World’s executives forced changes to the storyline to make the Soviets into the villains. Instead of accidentally firing a missile from their space platform, the Soviets now launch the missile on purpose. It’s obnoxious and undercuts one of the better aspects of the original: the position of Japan between two evenly balanced super powers. Also undercutting this is the removal of most of the prime minister’s scenes, taking away the film’s best dramatic moments.

Credit where it’s due: Godzilla 1985 dropped the hilariously out-of-place J-Pop song from the end credits, a literal love song to Godzilla done without any irony. (“Take care now, Godzilla, my old friend, | Sayonara ‘til we meet again.”) New World replaced the song with a suite of Reijiro Koroku’s orchestral score, which is generally excellent. New World also fashioned a nifty main title sequence where the fiery letters GODZILLA slowly burn across the screen, accompanied by Koroku’s superbly sinister theme.

Despite all the brickbats I’ve hurled at Godzilla 1985, I wish it had been included on the new Blu-ray. The US version has historical value for Raymond Burr alone, and the camp factor means it still has fans. But Kraken Releasing would have to pay separate licensing fees for Godzilla 1985 and probably didn’t have the budget for it. In its place is an English-language audio track, which is the dub Toho commissioned for International release. As dubs go, it’s passable. New World made their own dub for Godzilla 1985, which is better, although not in stereo.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

So basically this was just a sequel to the first 85 minutes of the original Godzilla.

This might have been the first Godzilla movie I saw in the theater? Well, the first first-run Godzilla I saw in the theater, anyway — I think I saw Megalon and Mechagodzilla as part of summer kiddy matinee programs. I was young enough that it (Godzilla 1985) did impress me somewhat, but seeing it again on Blu-ray, yes, it’s really not that great.

Y’know, its modern “Re-Make” culture that helped turn me against political correctness.

I watched -as a child in theaters lots of Godzilla movies – not that old rather like the now classic animation Rugrats loving “Reptar!” the cheap “Saturday Matinee” at the theatre to keep the kids going out but not getting in trouble setting fires and such. So, movies from decades past were “New” to me. I also liked “African Explorer” movies where people went into the Jungles of “Darkest Africa” seeking some treasure but the Natives were restless – and hungry…

Nice to hear how dismissed most of them are – “The Showa Era”… I presume Mothra, Gihidra, MechaGodzilla… All in the trash can?

And the worst thing is, they already did this. The mid 90s Godzilla -and this was the “Pointless, degrading re-make” that helped set me off – using a grotesque amount of money – enough to film a dozen “Showa” movies… I’d want that a thousand times! But they spent tons of computer effects to try to out-do Jurassic park (failed despite 100x the computer power) and make a monster that at any scale could NOT be “A man in a suit”…

I can almost understand -though still hate with a passion- dozens of “African Explorer” movies I remember being “lost films” due to Political correctness. They moved them from the big cities to small, rural area (or told them to destroy the reels and that order was ignored) for cheap matinees. I just saw them as good, scary movies, weren’t any real blacks in my town for a long time. Thought the Cannibals kicked rear, matter of fact! I remember asking my Dad why Tonka didn’t make real cars, because he was panicking about a 3mph fender bender and Tonka made cars Godzilla could kick 20 feet into the air into a building and roll and stand up and even the paint wouldn’t be scratched… Got told about “Square/Cube law”…

But, re-making the Godzilla to pointlessly re-do the initial plot – and all those other cool giant monsters are gone in the main storyline?

Pass…

Really, they got to let things DIE. Where’s the money for NEW stories, NEW writers, NEW things? Are they going to just keep Chewing and Spewing the same things again?

From the 90s there’s a neat book – “Random acts of Senseless Violence” by Jack Womack. Might technically be sci-fi or cyberpunk, but very near future very realistic – and coming true. One of the background elements in America’s decline is the “Re-Release” of movies. He predicted as the public’s money drained movie companies would “Re-Release” movies to avoid the cost of making them again and feed off nostalgia… Thus the father of the protagonist was laid off… (he had been an up and coming scriptwriter, starting to earn the good money then back to the college job)

But – whoop de deee… How reality can out-do even crazy fiction…!

Movie companies are terrified of a flop or risking money on new writers, new stories so they spend much, MUCH more money re-making the SAME stories again and again, and when they FLOP they go right back to doing it again… I mean in the fiction they re-released existing movies with fanfare to gain box office sales…literally cheap but low risk.

I think I can say it’s crazy – “Doing the same thing again and again, expecting different results” – well that is what they are doing, even as the “Re-Make” is bitterly souring.