Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar Saga: Back to the Stone Age

I’ve now arrived at that period in the Pellucidar series. The period any Edgar Rice Burroughs series eventually reaches: the late 1930s. I took a break from my Pellucidar retrospective to look at Burroughs’s 1913 horror-adventure novel The Monster Men just to delay taking the next step and driving my snowmobile headfirst into the hard ice of the poorest period of Burroughs’s career. But now I’m here and must accept the facts of the late ‘30s and an author trudging through his weakest creative years. Maybe it won’t be so bad. Perhaps I’ll discover a few pleasures in the last three Pellucidar books.

I’ve now arrived at that period in the Pellucidar series. The period any Edgar Rice Burroughs series eventually reaches: the late 1930s. I took a break from my Pellucidar retrospective to look at Burroughs’s 1913 horror-adventure novel The Monster Men just to delay taking the next step and driving my snowmobile headfirst into the hard ice of the poorest period of Burroughs’s career. But now I’m here and must accept the facts of the late ‘30s and an author trudging through his weakest creative years. Maybe it won’t be so bad. Perhaps I’ll discover a few pleasures in the last three Pellucidar books.

Anyway, enough procrastination. I’m getting on the snowmobile.

Our Saga: Beneath our feet lies a realm beyond the most vivid daydreams of the fantastic … Pellucidar. A subterranean world formed along the concave curve inside the earth’s crust, surrounding an eternally stationary sun that eliminates the concept of time. A land of savage humanoids, fierce beasts, and reptilian overlords, Pellucidar is the weird stage for adventurers from the topside layer — including a certain Lord Greystoke. The series consists of six novels, one which crosses over with the Tarzan series, plus a volume of linked novellas, published between 1914 and 1963.

Today’s Installment: Back to the Stone Age (1937)

Previous Installments: At the Earth’s Core (1914), Pellucidar (1915), Tanar of Pellucidar (1929), Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929–30)

The Backstory

The ending of Tarzan at the Earth’s Core set the scene for a direct follow-up. Wilhelm von Horst, one of the German members of the O-220 expedition to Pellucidar to rescue David Innes, was still stranded somewhere in the inner world, and Jason Gridley chose to remain in Pellucidar to locate him. But other projects and business concerns prevented Burroughs from moving fast into writing this proposed sequel. He wouldn’t start work on the new Pellucidar novel until January 1935, writing it under the working title Back to the Stone Age: A Romance of the Inner World. It took him eight months to finish the 80,000-word novel, an unusually protracted length for him. And that was only the beginning of the difficulties.

Burroughs had trouble finding a magazine to serialize the book, an unfortunate new experience for him. His two most dependable markets, Blue Book and Argosy, both rejected the manuscript. After a change of editors at Argosy, the magazine reconsidered the work, but only if ERB made revisions to de-Germanize protagonist Wilhelm von Horst. (Germany wasn’t at a high period of popularity in the late 1930s.) Burroughs complied, making some alterations to von Horst’s backstory and referring to him as “the European” rather than “the German” in descriptions. Argosy paid Burroughs a small sum for the serialization rights, far less than he was making only a year earlier.

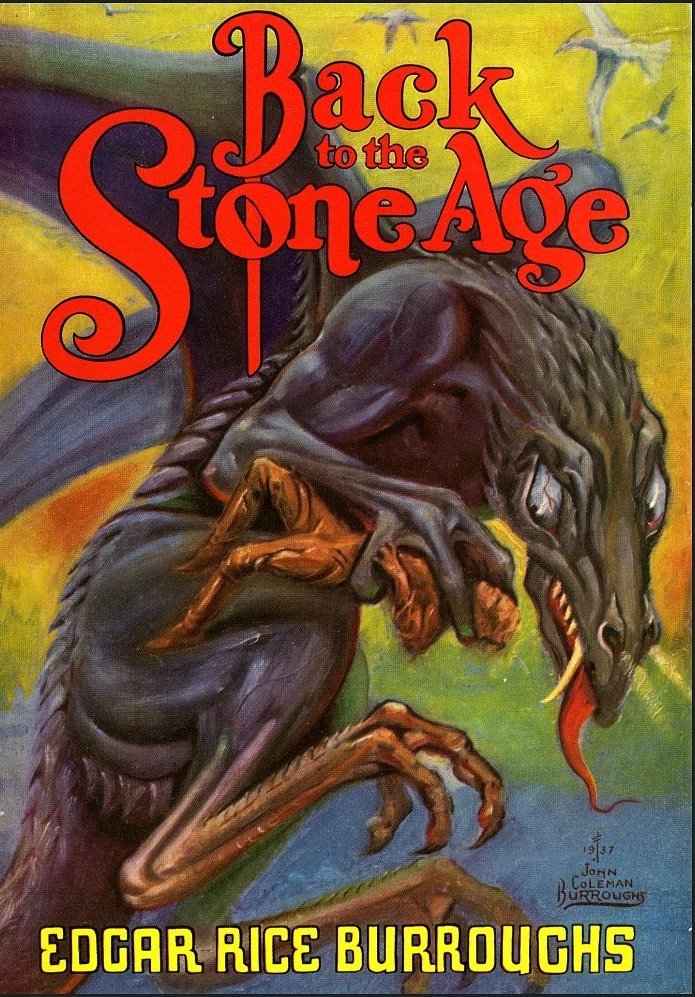

Back to the Stone Age debuted in Argosy Weekly (where it was retitled Seven Worlds to Conquer for no reason I can tell) in five installments from January 9 to February 13, 1937. ERB Inc. published the hardcover — all of Burroughs’s book publications were now done through his own company — in September of the same year. Burroughs’s son, John “Jack” Coleman Burroughs painted a thrilling cover and supplied seven black-and-white interior illustrations. There’s no question Jack Burroughs was an inferior artist to J. Allen St. John, ERB’s principal artist for decades, something even Jack admitted. But he improved with each outing, and the ERB Inc. edition of Back to the Stone Age is one of his early triumphs.

The Story

The Story

This is the story of the one who was lost. (But aren’t we all lost in Pellucidar?)

With no prologue, we land in the middle of Chapter 6 of Tarzan at the Earth’s Core and the massive beast stampede that breaks apart the expedition from dirigible O-220. The shouted dialogue is the same, but the perspective has shifted. Now we see the madness from the point of view of Lt. Frederich Wilhelm Eric von Mendeldorf und von Horst, who escapes the crush into the forest. Soon he’s lost in trackless and timeless Pellucidar, with no sense of where to search for his companions or the camp.

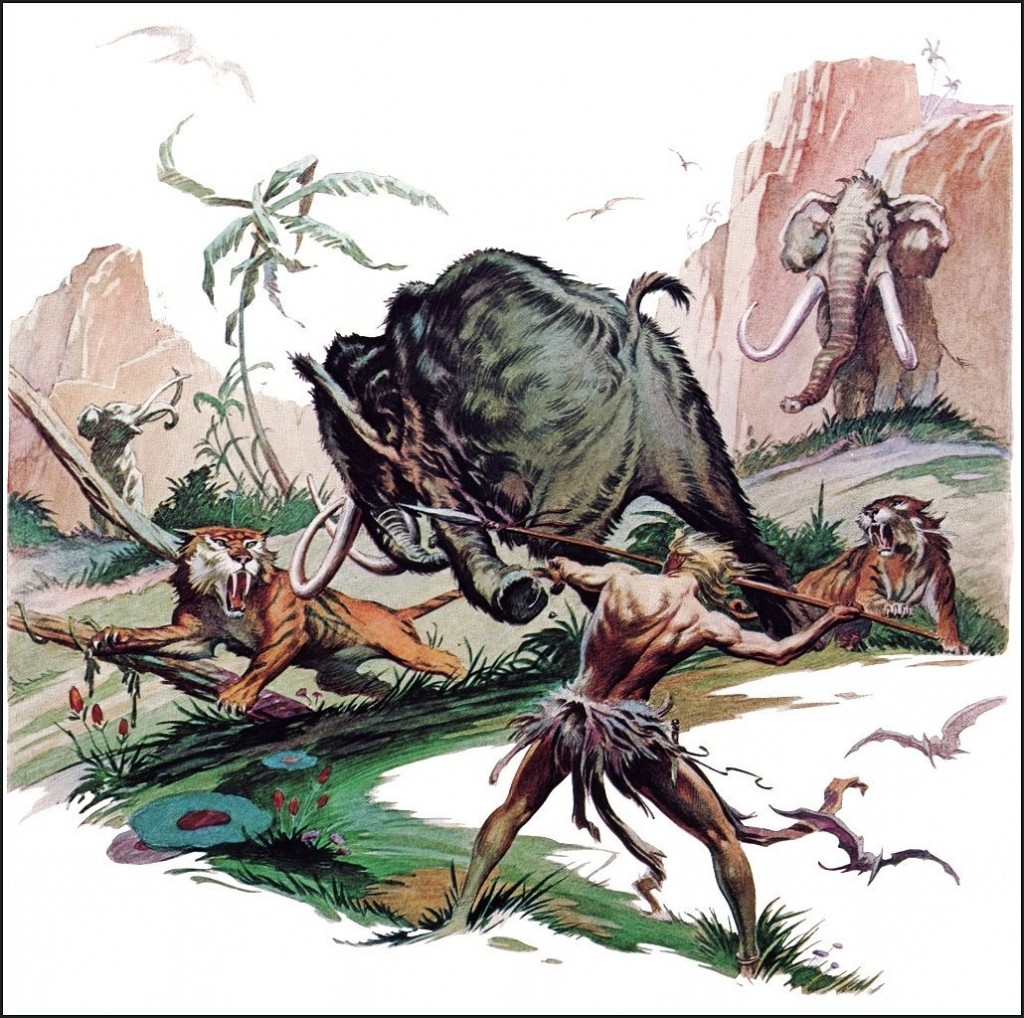

Almost immediately, a flying marsupial reptile called a Trodon seizes von Horst and places him in its nest — the first of a series of captivities that fill up the rest of the book. Von Horst manages an escape along with another captive, Dangar of the land of Sari. Von Horst isn’t aware that Sari is where Jason Gridley is located, and he’s soon distracted from reaching this destination when he encounters the beautiful La-ja during his next scheduled imprisonment, this time with the cannibal Bastians. Von Horst channels his energies and his increasing reversion to the mental psychology of the Stone Age either to search for La-ja or to find his way to her homeland of Lo-har, where her father is the chieftain and an angry suitor named Gaz is waiting for her.

During von Horst’s wanderings, he ends up imprisoned by the tusked Gorbuses, then the mammoth-men, and then the bison-men (Ganaks). He also picks up a helpful travel companion, a massive mammoth named Old White. Von Horst easily bests numerous burly challengers, escapes from a trap in a canyon with a rush of mammoths and sabertooths, and eventually wins the love of La-ja before David Innes’s expedition at last locates him. (Jason Gridley decided just to go back to Tarzana and fiddle with his radio devices, apparently.)

The Positives

More than fifteen years have passed (but who can count here in Pellucidar?) since I last read the solo adventures of Wilhelm von Horst at the earth’s core … and it’s better than I recall. Back to the Stone Age is superior to many other Burroughs novels of this period, such as the Venus series. One of the reasons is simple: ERB’s prose contains more beauty and energy here than was standard during the late ‘30s. Burroughs sounds like he’s having fun writing this, even if he still falls into loose and episodic plotting. Perhaps writing the book in spurts over eight months kept his prose from growing stale; he was energized each time he came back. There are a number of poetic passages and fewer occurrences of lazy and awkward writing. The opening chapter is stylistically impressive: despite its backstory infodumps, there’s plenty of writing that feels almost impressionist.

The Big Idea Burroughs presents in Back to the Stone Age is hidden in plain sight in the title. Von Horst experiences a change from a modern European man into a primitive human: “He hunted as they hunted, ate as they ate, and often found himself thinking in terms of the stone age.” The theme doesn’t hold up to scrutiny and should’ve been explored in more depth, but it does give the loose story extra pegs to hang from — and Burroughs’s writing is often elegant during these sections.

Von Horst was a minor figure in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, someone easy to dismiss among the O-220 crew. But he makes an interesting leading man because often drips with sarcasm and humor. This sets him apart from the previous above-worlders who’ve adventured in Pellucidar, and he’s more fun to hang around than dull Tanar. Von Horst doesn’t take himself too seriously, but he doesn’t collapse into cluelessness and incompetence the way Carson Napier does in the Venus books.

Von Horst was a minor figure in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, someone easy to dismiss among the O-220 crew. But he makes an interesting leading man because often drips with sarcasm and humor. This sets him apart from the previous above-worlders who’ve adventured in Pellucidar, and he’s more fun to hang around than dull Tanar. Von Horst doesn’t take himself too seriously, but he doesn’t collapse into cluelessness and incompetence the way Carson Napier does in the Venus books.

La-ja’s quick turn against von Horst soon after meeting him is a predictable development; it looks as if Burroughs is setting up a standard artificial romance barrier, with misunderstandings or mutual arrogance keeping fated lovers apart. But then something different occurs. When La-ja is obstinate about not coming along on a rescue because of her attitude toward von Horst and the sensible concern that her captors will violently retaliate, von Horst knocks her unconscious to carry her off. Now she’s really enraged: “If you think I am going to be your mate now, you are mistaken.” Here’s a blockade to romance that makes sense. Of course La-ja would be furious at von Horst: he hit her! Even von Horst is shocked at what he did, and wonders if this is part of his reversion to a Stone Age mentality. It’s natural that it requires the remainder of the book for von Horst to gain La-ja’s love.

Another place where the otherwise conventional romance works is the antagonistic repartee between La-ja and von Horst, particularly after he learns about Gaz, the man planning to wed La-ja in her homeland. The German teases her about whether Gaz could pull off this-or-that incredible feat, while La-ja executes a running “I would like you, but…” routine. Von Horst’s sarcastic humor clicks in this relationship, with La-ja pestering him about how he makes little sense each time he uses a colloquial phrase no Pellucidarian could understand. So of course he keeps using them.

But what’s best about the von Horst/La-ja romance is that it stays on the backburner for most of the book. La-ja isn’t around von Horst long enough to allow readers to grow weary of their banter. Absence makes the heart grow fonder … or at least it lets readers imagine the relationship developing while enjoying von Horst playing around with a mammoth.

Speaking of which, Old White, The Killer is the best supporting character and the book’s biggest win. Animal companions are common in Burroughs, and the Pellucidar stories already had a great one in Raja the hyaenodon in the second novel. But Old White is something special: he’s almost von Horst’s superior in their relationship, playing around with the man and exhibiting a sense of humor as he teases him and dangles him upside down from his trunk. Old White always arrives right when he’s needed, not just for von Horst, but for readers, since the mammoth ally helps create a sense of a throughline in an episodic story.

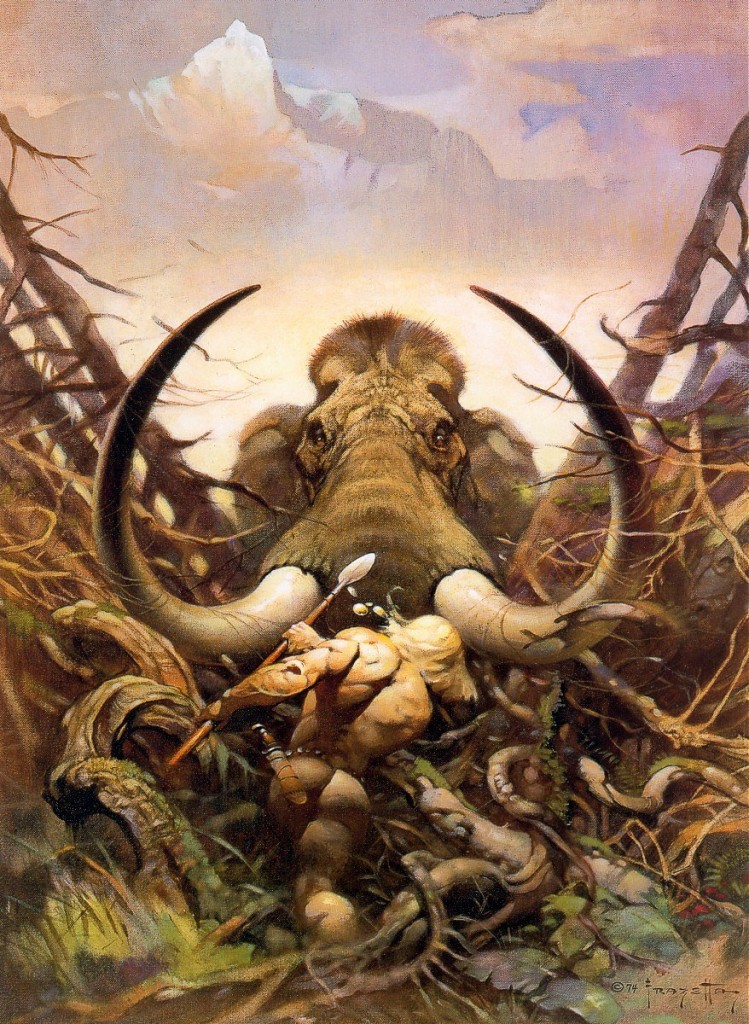

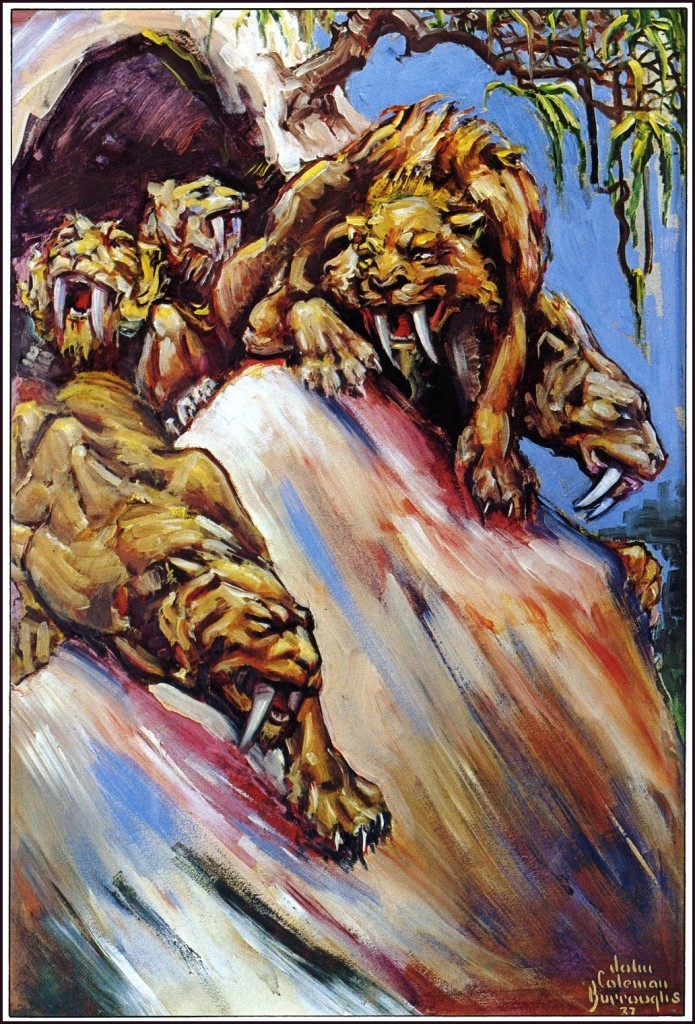

Old White is at the center of the book’s two exceptional moments. When von Horst first encounters the enormous creature, Old White is in a trap with bamboo spears stuck into his side. Von Horst draws the spears out in a scene that’s more gentle and loving than anything the hero experiences with La-ja. When Old White returns, it’s to rescue von Horst from the crush of tarags (sabertooths) and other mammoths in the “narrow canyon,” which is the mammoth-men’s equivalent of an arena fight. Von Horst turns into a rag doll in this sequence: Old White scoops him up with his trunk, drops him on his back, then turns about and batters through the tarags to freedom. Old White even hurls a tarag into the crowd where it goes on a violent tear. As far as thrill sequences go, this ranks with the best Pellucidar has to offer.

Old White is at the center of the book’s two exceptional moments. When von Horst first encounters the enormous creature, Old White is in a trap with bamboo spears stuck into his side. Von Horst draws the spears out in a scene that’s more gentle and loving than anything the hero experiences with La-ja. When Old White returns, it’s to rescue von Horst from the crush of tarags (sabertooths) and other mammoths in the “narrow canyon,” which is the mammoth-men’s equivalent of an arena fight. Von Horst turns into a rag doll in this sequence: Old White scoops him up with his trunk, drops him on his back, then turns about and batters through the tarags to freedom. Old White even hurls a tarag into the crowd where it goes on a violent tear. As far as thrill sequences go, this ranks with the best Pellucidar has to offer.

When the Ganaks capture von Horst, he goes on a casual killing spree that’s out of character but utterly hilarious and the right type of bonkers the book needs as the final stretch turns tedious. When the Ganak chief claims von Horst cannot kill people with arrows (he derides them as “little sticks”), von Horst demonstrates their lethality by nonchalantly shooting an arrow into the chief’s heart and killing him. When a fight erupts between two competitors for the chieftainship, Kru and Tant, von Horst proclaims “Kru is chief!” and shoots Tant dead. Why? Because he could. It’s nonsensical, but I like it when ERB goes off the rails like this.

The Negatives

Enjoyable prose, witty exchanges, and romps with a mammoth can only carry an adventure novel so far when the plot is a series of episodes that run the hero through identical circumstances over and over. Back to the Stone Age divides into a sequence of four captivities among four different peoples, with the Trodon as a prologue. Von Horst is shoved from one imprisonment to the next without developing an actual objective. Since he doesn’t believe he has any chance of returning to the surface world, his only goals are sticking with La-ja or searching for her whenever he gets lost. He doesn’t know where he needs to travel or if there is any specific place he could travel. He changes his mind from episode to episode about his next destination, often based on a whim. Events swirl around La-ja’s land of Lo-har, and when von Horst finally stumbles there the story rapidly ends.

With the exception of the time when he’s paralyzed in the Trodon’s nest (a tense opening), von Horst never acts like he’s in serious danger as a captive. Usually, he physically bests one of his captors right away — taking this to an extreme with the show-off killings among the Ganaks — but then stays put until he has a better idea of where to hunt for La-ja. He could make an escape at almost any point, and this doesn’t create suspense or make readers eager to pick up the book again once they put it down. The only time when it feels as if any of von Horst’s humanoid captors have put him in true jeopardy is when the mammoth-men force him into the narrow canyon to face the rush of saber-tooths and mammoths.

Burroughs uses the mammoth-men as an excuse to create yet another satirical picture of domesticity flipped upside down: women choose whom they wish to marry, and if the chosen man loses a fight with the woman’s father, he’s forced to marry her. In other words, the woman isn’t the prize for winning the fight, but rather a punishment for losing it. Marriage continues the violence, with wives beating and subduing their husbands: “Marriage to them meant a struggle for supremacy. It was a 50-50 proposition of their own devising — they took fifty and demanded the other fifty.”

Burroughs uses the mammoth-men as an excuse to create yet another satirical picture of domesticity flipped upside down: women choose whom they wish to marry, and if the chosen man loses a fight with the woman’s father, he’s forced to marry her. In other words, the woman isn’t the prize for winning the fight, but rather a punishment for losing it. Marriage continues the violence, with wives beating and subduing their husbands: “Marriage to them meant a struggle for supremacy. It was a 50-50 proposition of their own devising — they took fifty and demanded the other fifty.”

Burroughs tried this gender-reversal gimmick a number of times in his late-period books. It serves as the dreadful opening of Carson of Venus with the Samary people, and it showed up in Pellucidar among the denizens of Garb in Tanar of Pellucidar. The gender role switch rarely worked, falling flat either as comedy or satire and instead feeling juvenile or simply ugly and unpleasant. In the case of the mammoth-men, it over-complicates the story with a web of new relationships. This tricks readers into thinking they have to understand the family trees and which woman wants which man to marry her. But it’s ephemera stalling the action until the sabertooth and mammoth stampede, and then it never matters again.

The Gorbuses offer the promise of a world-shattering creative concept, potentially one of the major revelations about Pellucidar. When von Horst and La-ja are captives in the Gorbuses’ caverns, a sympathetic Gorbus named Durg tells them about his memories of a past life where he murdered someone. Durg explains that all his people harbor similar memories of guilt in a previous existence, and these past-life crimes are why they’re now Gorbuses. Von Horst realizes Durg is using words and ideas he couldn’t know as a Pellucidarian, and he’s using them in English. Does this mean the Gorbuses are subhuman reincarnations of surface dwellers who committed crimes? Has von Horst discovered the origin of the human concept of karmic punishment in the afterlife? This seems too supernatural for Burroughs, who usually sticks to weird science rather than outright fantasy. But it’s an explanation von Horst finds hard to avoid…

…but he avoids it anyway, as does the book, since the karmic reincarnation concept sticks around for only a page and a half. Were you excited to see where this was going? Too bad. You aren’t going to find out anything more and the topic won’t be raised again. Even von Horst never thinks about it further. It feels as if Burroughs planned to do more with the Gorbus reincarnation mystery, then jettisoned the idea and never went back to remove references to it from the final version. Whatever the reason it’s here, this fascinating concept turns into a major frustration.

Whenever Burroughs turns away from focusing on the Stone Age reversion theme, it falls apart. We’re told von Horst is devolving into a primitive human of Pellucidar, but each time he opens his mouth and more modern witticisms tumble out, the idea evaporates. Burroughs makes a last hard play to stick the theme in the end chapter, explaining that von Horst’s love for La-ja at last overcoming his pride is an example of how “savage Pellucidar has claimed him as her own.” But love overcoming pride happens in many other ERB novels, and there’s psychologically little difference in how it goes down here. The hero isn’t much different in the last chapter than he was in the first. The book closes on the observation that von Horst “combined the psychology of the cave man, that he had acquired, [with] all the valuable knowledge of another environment.” This isn’t going “back to the stone age” so much as figuring out how to adapt to life with primitive people.

Whenever Burroughs turns away from focusing on the Stone Age reversion theme, it falls apart. We’re told von Horst is devolving into a primitive human of Pellucidar, but each time he opens his mouth and more modern witticisms tumble out, the idea evaporates. Burroughs makes a last hard play to stick the theme in the end chapter, explaining that von Horst’s love for La-ja at last overcoming his pride is an example of how “savage Pellucidar has claimed him as her own.” But love overcoming pride happens in many other ERB novels, and there’s psychologically little difference in how it goes down here. The hero isn’t much different in the last chapter than he was in the first. The book closes on the observation that von Horst “combined the psychology of the cave man, that he had acquired, [with] all the valuable knowledge of another environment.” This isn’t going “back to the stone age” so much as figuring out how to adapt to life with primitive people.

Burroughs could have explored the reversion theme deeper: what if rather than becoming more accustomed to primitive ways, von Horst started to pick up the special directional sense of the Pellucidarians? Considering the many other weird occurrences in these novels, it’s not a stretch to imagine Pellucidar changing a surface dweller to have some of the peculiar abilities of the natives. It’s odd ERB hadn’t tried something like this earlier, sort of a reverse on how Pellucidar reduced Tarzan’s skills in the previous book. A “tuned-in” von Horst would also fix the listless wandering and repetition problems, giving the hero a solid direction to follow — a goal! — during the second half.

Holding back Gaz, ostensibly von Horst’s rival for La-ja, for the big finale might have worked if Gaz ended up as anything worth the wait. La-ja uses him as a tease to needle von Horst, and readers know Gaz is going to show up eventually. But when he does make his entrance, Gaz isn’t anything special, just another of the bruisers von Horst has beaten without much effort throughout the book. And von Horst then beats Gaz without much effort. Maybe if Gaz were mounted on his own pet mammoth, and von Horst and Old White charged them for a tusk-to-tusk, spear-to-spear duel … well, anything more exuberant than what we ended up with would’ve been acceptable.

With no prologue featuring the pseudo-ERB to set up the story and offer a recap of previous events, exposition dumps clog the first chapter. The pseudo-ERB framing chapters are useful tools for exposition and setting the mood — and they’re often meta-weird, which always generates some good discussions. The absence of one forces Back to the Stone Age into a clumsy opening. In a later chapter Burroughs inserts a quick mention that Jason Gridley is located in Sari where he’s setting up a party to look for von Horst, which is the type of material a prologue should’ve covered. Instead, it’s done as an awkward cut-away from von Horst’s POV that attempts to give some shape to his wanderings.

Craziest Bit of Burroughsian Writing: One of the exchanges between von Horst and La-ja:

“In Pellucidar, I shall never die of ennui.”

“I do not know what you mean. I do not know what ennui is.”

“No Pellucidarian ever could,” laughed von Horst…

Most Inventive Idea: The Gorbuses might be reincarnations of murderers from the upper world. If only Burroughs actually explored this beyond a single conversation!

Best Creature: The Trodon, a winged marsupial reptile with a paralyzing tongue.

Carson Napier Memorial Foolishness Award: Von Horst suggests to La-ja that they slip out of Basti “after dark.” La-ja obviously has no idea what he’s talking about.

Here’s a way to tell time: “…for no matter how much the timelessness of Pellucidar might deceive the mind of man it could not befuddle the law of combustion — fire would consume wood as quickly and embers would remain hot as long here as upon the outer crust and no longer.”

How about a sequel? The loose ends are tied up. This is a good place to stop. I’d rather Ed put the prose skills he shows here to use on the Tarzan or Mars series.

Next: Land of Terror

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.