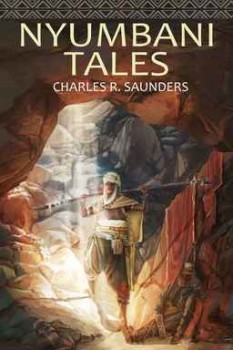

Stories from a S&S Griot: Nyumbani Tales by Charles R. Saunders

“I am going to tell a story,” the griot says.

“Ya-ngani!” the crowd responds, meaning “Right!”

“It may be a lie.”

“Ya-ngani.”

“But not everything in it is false.”

“Ya-ngani.”

The griot begins his tale.

from “Amma” by Charles R. Saunders

For those unfortunates unacquainted with Charles R. Saunders and the tales he’s woven, you can read plenty about them here at Black Gate. Suffice it to say he is called the father of sword & soul. Starting in the 1970s, he took the elements of swords & sorcery — mighty heroes, beautiful women, monsters, deadly magic, and more monsters — and turned them to his own purpose.

For those unfortunates unacquainted with Charles R. Saunders and the tales he’s woven, you can read plenty about them here at Black Gate. Suffice it to say he is called the father of sword & soul. Starting in the 1970s, he took the elements of swords & sorcery — mighty heroes, beautiful women, monsters, deadly magic, and more monsters — and turned them to his own purpose.

A fan of sci fi and fantasy growing up in the 1950s and 60s, by the time he graduated college in 1968, he was frustrated with a lot of what he was reading. As he recounted in an interview with Amy Harlib in The Zone:

I began to realise that in the SF and fantasy genre, blacks were, with only few exceptions, either left out or depicted in racist and stereotypic ways. I had a choice: I could either stop reading SF and fantasy, or try to do something about my dissatisfaction with it by writing my own stories and trying to get them published. I chose the latter course.

It was to the great benefit of heroic fantasy that Saunders made the choice he did. In addition to helping expand the horizons of the genre beyond the European settings that dominated it back then, he also created two monumental characters.

Imaro is the outcast warrior who eventually finds his destiny as champion against the forces of evil. Dossouye is an exiled warrior-woman from the kingdom of Abomey. The stories and novels featuring Imaro and Dossouye belong on the shelves of any S&S fan. If you haven’t read them yet, I suggest you snag copies of Imaro: Book I and Dossouye, clear off whatever else you’re reading, and get started.

Let me take a break from pontificating and actually tell you something about Nyumbani Tales. Nyumbani is the name of Saunders’ heroic fantasy version of Africa, and the setting for the Imaro stories. Its kingdoms and cultures are modeled on real-world African ones.

The thirteen stories here, some featuring characters from the Imaro stories, explore and expand Nyumbani beyond the regions charted in the four Imaro novels. All the stories were previously published, about half before Imaro: Book I, in various ‘zines and anthologies. Some are straightforward S&S, while others adapt traditional stories from various African regions into a more standard heroic fantasy style. Several have been cleaned up by Saunders for this collection.

The book’s opener, “Katisa” is the result of an attempt by Saunders to write a novel about Imaro’s mother. While he never sought publication for that novel, the story of Katisa’s escape from a sorceror’s clutches, and her subsequent exile from her people, the Ilyassai, remained with him. It’s a good introduction to the mix of African elements, strong women, and horror that feature in Saunders’ stories.

One of the stars of the Imaro stories is the ex-court jester and scholar, Pomphis. Set in the days when he’s still in service as a jester, he takes center stage in two comic tales, “The Blacksmith and the Bambuti” and “Pomphis and the Poor Man.” They’re short and funny and I don’t want to give anything in these stories away. Of the former, Saunders writes that he “had more fun writing this tale than any other to date.”

two comic tales, “The Blacksmith and the Bambuti” and “Pomphis and the Poor Man.” They’re short and funny and I don’t want to give anything in these stories away. Of the former, Saunders writes that he “had more fun writing this tale than any other to date.”

Another player from the Imaro stories makes his appearance in “The Nunda.” Prince Majnun is content to lack ambition and spend his time with wine and women. When he endangers a trade deal with another kingdom, his father sends him off to investigate rumors of a mysterious beast ravaging the countryside. The story is a good mix of mystery, action, and horror.

“Death-Cattle of Djenne” is the story of which Saunders says it was “the first time I felt I had ‘got it right’ in my quest to transform African folktales into North American-style fantasy stories.” During a period of terrible drought, when the rural cattle-herding people of Djenne-the-Land are ready to rise up against the better-off people of Djenne-the-City, a strange offer comes their way:

At first glace, the intruder seemed to have the lean, sinister aspect of the Turaag, a rapacious nation of masked nomads who raided the length and breadth of the Sahanic lands. But closer inspection showed that despite his mask, this man was no Turaag, for they always wore bright blue garments. The stranger’s clothing, which resembled burial cerements, was a pale, spectral shade of gray. In the narrow strip of dark flesh that lay between his turban and mask, the mysterious herdsman’s eyes burned like cold flames in hollow pits.

“I have a herd to sell to the people of Djenne-the-Land,” he said in a distant, imperious tone.

This dark story, possessed of a terrible central secret, is one of the book’s several highlights.

“The Return of Sundiata” is an epic story of gods who walk like men. War has come unbidden to the kingdom of Kotoko. Under the direction of a mighty sorceror named Oshahar, the enemy armies of Sao have ravaged Kotoko’s countryside and besieged its capital. When all hope seems lost, a young woman named Kiemba puts her trust in the legend of the ancient hero Sundiata, and risks everything to summon him from beyond death.

“Two Rogues” and “Okosene Alakun and the Magic Guinea Fowl” are another pair of comedies. The first pits two con men, one a former soldier and the other a sorceror, against each other, even as they plan a scam with each other. In the latter, adapted from a Nigerian folktale, a lazy husband with an unpleasant wife learns the hard way about making wishes. So many of the comic tales I read aren’t funny. Rest assured, these are.

“Amma” elicited a minor cloud of flak when Gerald Page inlcuded it in DAW Books’ The Year’s Best Horror VII. Saunders himself leaves it open to the reader whether it’s horror or only fantasy. Told as a tale-within-a-tale, the story opens with a new griot coming to the city of Gau. After attracting listeners’ attention with songs, he settles down to tell them a tale of death, love, and sorcery.

During a terrible war, Babakar iri Sounkalo’s fields were burned and his wife, Amma, and their daughters were raped and killed. Unsure of what to do, he is startled to see a beautiful woman emerging from the lifeless Tassili wasteland. A fellow victim of the raiders who destroyed Babakar’s life, and also named Amma, he takes her in when she offers to help him reclaim his land and plant new crops. Over time he falls in love with this other Amma. When his and others’ crops are destroyed in the night by a mysterious herd of gazelles, it is clear evil is loose in the land. This is my favorite of the collection’s stories.

One of the things lacking in many myths and folktales is any real characterization. Often — and usually by design — characters are used like puppets for the sake of the lesson at hand. Contemporary stories mixing psychologically believable characters with folktale elements are usually a fail, in my reading experience, trying to apply current mores and social attitudes to ancient tradition.

One of the things lacking in many myths and folktales is any real characterization. Often — and usually by design — characters are used like puppets for the sake of the lesson at hand. Contemporary stories mixing psychologically believable characters with folktale elements are usually a fail, in my reading experience, trying to apply current mores and social attitudes to ancient tradition.

In “Amma,” Saunders does none of that. He manages to “transform the folktale,” explore the psychology, stay true to the culture, and tell a story of power and resonance. Babakar is a (sadly) utterly believable man who has seen horrific tragedy, now willfully blind to reality in order to reclaim the sort of life and love he once had.

In “The Singing Drum,” a beautiful young girl, known for her unparalleled singing abilities, is captured by a mysterious figure who rises up out of a river. When a stranger appears in town with a drum that sings on command, the perceptive ear of the man who loves her leads to her rescue.

Saunders brings on the big monster in “Khodumodumo.” A goatherd is shocked when a great thing pulls itself out of the earth:

Then he heard it … a soft, slithering sound that rose from the depths of Damballah’s Hole …

Gaping in disbelief, the goatherd watched as something glistening and huge lapped over the side of the defile. Shapeless, featureless, limbless … the thing heaved yard after yard of pearlescent bulk onto the pasture. With frightening speed, several protuberances shot from the main body of the thing toward the terrified animals. Before the goats could move, they found themselves surrounded by walls of living slime. Bellowing in panic, the animals attempted to flee.

But slits in the pseudopods suddenly gaped open like great, vertical mouths, and engulfed the goats like gigantic snakes. In a matter of moments, the entire herd disappeared from sight.

The creature continues to grow as it devours more and more people and animals. Before the tale’s end, the thing has grown so large it needs to push hills out of its way.

In “Mbodze,” a young potmaker accidentally frees a savage zimwe, or ogre, named Mbodze from the rock in which he was imprisoned. In turn, Mbodze takes her prisoner and plans to make her his bride. From the legends she recalls, all the women he took as brides, he fattened up and then ate. Her only hope for salvation lies with a sparrow that tells her:

“Fear not, Marimira. Tonight, I will come to you and show you the way to free yourself from Mbodze.”

In the introduction to “Ishigbi,” Saunders writes that in some parts of Africa twins are considered accursed, with the opposite in other regions. “Ishigbi” uses both beliefs to tell a story of revenge that involves ravenous ensorcelled undead and a god and goddess.

regions. “Ishigbi” uses both beliefs to tell a story of revenge that involves ravenous ensorcelled undead and a god and goddess.

The final tale, and the most unsettling, is “The Silent Ghosts.” The Silent Ghosts of the title are slavers, believed to be demonic, who raid villages at night, unseen. They and their depradations figure in the background, only once making an appearance that is both unexpected and completely devastating. Despite the presence of dinosaurs, a Witch-Smeller, and a herd of ramapaging mastodons, this is a story of love and jealousy. Love of a woman and family, jealousy of power. A testament to Saunders’ skills, the finale of this story is stuck deep in my brain and won’t be shaken loose easily.

Saunders writes with clarity, avoiding the worst faux-archaicisms that drown lesser S&S authors’ work. He can be wonderfully poetic at times, especially in his descriptions of the land, but it’s never cloying. At the same time, he tells stories set not in our present, but in a past with different customs and beliefs. Characters act and react in ways that feel alien and yet perfectly natural in the context of the story. Saunders achieves that markedly rare effective synthesis of the mythic with the believable. It’s a trait he shares with other great S&S writers.

I consider Charles Saunders one of the absolute best swords & sorcery writers; someone who stands alongside Howard, Leiber, and Wagner. Of the 70s and 80s golden age of the genre, he’s one of the few talents still writing, and writing at the level he did forty years ago. You can check out his latest work, Abengoni: First Calling to see that. (Side rant: I found only two significant reviews of this book; mine here at Black Gate and one over at Castalia House. If that’s not criminal neglect, I don’t know what is).

In a better world, where an author could find the audience he is worthy of, this book would have been put together decades ago and would still be discussed with fervor. DAW, and later Night Shade, wouldn’t have dropped Saunders, leaving Imaro in limbo for years at a time. Instead, it’s taken 35 years since the last of the stories included in Nyumbani Tales was published, and the dedication of Milton Davis to help make this collection happen.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about Western movies.

Sword & Sorcery groupies shared this in Goodreads. Glad to see more Imaro. Looking forward to reading the story of his mother. Thanks for the review, Fletcher/Blackgate.

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/18633403-black-gate-story-about-c-saunders-works

Thanks Fletcher. I’ve been waiting for a book like this since encountering Charles Saunders’ Imaro in DAW’s Year Best Fantasy series edited by Lin Carter. (I got them in a used book store but still a long time ago). I encounter some non-Imaro stories like the one from Hecate’s Cauldron and enjoyed them just as much as the Imaro stories. I hoping there would be a book collecting them. And just today I found out there was thanks to your review.

I bought the digital version so fast I didn’t check the price. I looked later and it was very reasonable.

Sold! Thanks Fletcher, you know gold when you read it.

@Seth – Glad to read that. There are no actual Imaro stories in this, just so you know.

@Charles – That’s cool. I first found out about him on Dale Rippke’s old HEROES OF DARK FANTASY site. I spent a couple of years tracking the original three DAW Imaro books down. Absolutely worth it.

I think he’s got another batch of stories to collect down the line.

@Wild Ape – Thanks. Maybe not always, but sometimes, sometimes. This is definitely S&S gold.

My students really enjoyed the three chapters/stories from Imaro we read together. If I run that Survey of Literary Fantasy class again, a lot of the syllabus will change, but Saunders is one of my keepers.

@Sarah – That’s really exciting to read. I hope Charles S. reads that.

I’m posting this late deliberately – decided it might be considered trollish if I did at the start.

Believe it or not, I like Charles Saunders. I’d actually read him years ago, but thanks to Black gate for helping find him again years ago. For all my foaming about “Political Correctness” I am loyal to “The Story” and respect a good story writer. My issue with the Politically Correct purge in the late 70s/early 80s was the ‘tokenism’ they did. I do . not . include Mr Saunders in that. He is a good writer and seems to have been self-published in ‘copy zines’ a lot before the books got printed.

Now, I like and hold to the old stereotypes – “Cush; Land of the Savage Cannibals” where Africa before it was civilized was a giant jungle where savage tribes warred with each other and killed and ate each other or sacrificed people to ancient devilish idols. (Egypt doesn’t count, it was Civilized by Atlanteans and/or Space Gods)

But – with Charles Saunders – wow! What imagination! He envisioned an Africa that the White man had not reached his hand to – but it had civilization, and not just a few cities with kings maybe and noble savage tribes but a vast land with many cultures and climates and tribes and languages – in essence as diverse as the wider world…

Just kidding there – intellectually I knew it. But grew up on lots of 40s, 50s “African Explorer” movies being shown decades later to kids on “Saturday Matinees” – good to keep a brat like me from getting into mischief and playing with fire. So, in my mind its “Cush: Land of the Savage Cannibals”. Even later stuff, like “yellow heat” from my favorite Creepy magazine, the Cannibal Gladiator in Conan, etc. kept reinforcing this so when the PC wall hit it seemed like a stupid lie.

Also, reading his website, I like a lot of Saunders’s inspiration. His “Ire and Brimstone” over cliches used…esp as he loved Sword and Sorcery but hated the stereotypes used. He was foaming mad over “The Man-Eaters of Zamboulla” a classic Conan story you can read for free on WikiSource – when it was one of my favorites in grade school when I read a crumbling Lancer paperback from a used bookstore. There’s a neat TEDex on writing where one lady argues all writers have an ‘inner pain’ – Charles Saunders pain was his favorite genre full of crude stereotypes that insulted him personally – Mine is disgust over the ‘politically correct’ bleach job the media did that did nothing good and the bland chew’nspew of existing properties.

The reason I’m posting this here is that I want to re-iterate I’m loyal to “The Story”. There’s a war brewing and Mr Vox Day is beating the drums, but he has ammo in the bland, pandering, token stuff out there. Matter of fact it’s a poorly managed ammo dump and all he needs to do is shoot sparks far enough beyond the huge, entrenched firewall. Even though I like adventure and non-politically correct stuff, and am fighting for the right to publish it and have it in ‘the market’ – I don’t want to create a backlash that only allows “Token, pandering” non-pc and racist stuff. Charles Saunders is a good writer in that he can write a story that while it might not 100% cater to whatever niche you see yourself in it is a good story. So, anyone sick of this fake ‘progressive’ pandering garbage who’s turning to older works including to embracing stereotypes, etc… Well I am too. But there are exceptions out there, and this man is one.