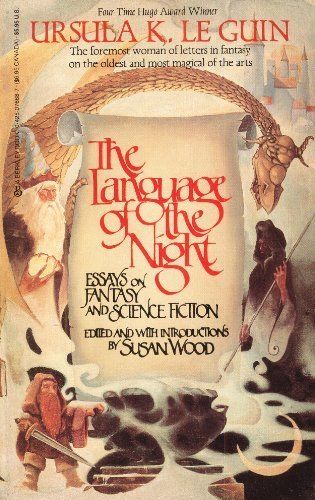

We All Need to Read More Le Guin: The Language of the Night by Ursula K. Le Guin

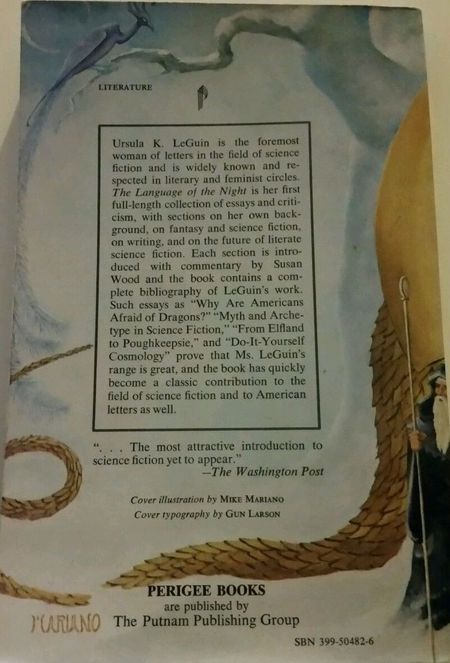

The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction

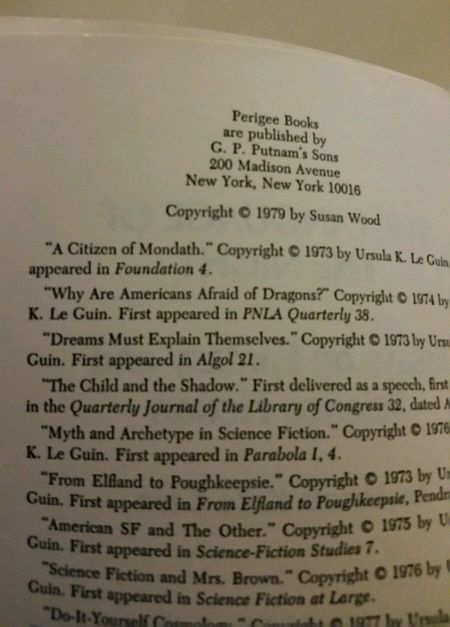

Ursula Le Guin, edited and with introductions by Susan Wood

Perigee Books (270 page, $4.95 in trade paperback, April 1979)

Cover by Mike Mariano

I need to read more Le Guin. It’s a deficiency I freely acknowledge and feel only slightly better about by adding that we all need to read more Le Guin. I know her through her short stories and the Earthsea books (which I will stack up next to the Narnia books any day), but I still have not read The Left Hand of Darkness or her other important science fiction works. I don’t have much of an excuse except time and the fact that I want to be what Le Guin calls a real reader. I want to be someone who truly digests, or rather, responds to what has been read; not, as I spent a good portion of my reading life, someone who simply goes from one book to the next, a consumer of literature, but still only a consumer regardless of the quality of what was consumed. So I read a book like Le Guin’s book of essays slowly, and I try to respond, synthesize, and recollect what she says not only about reading and writing science fiction and fantasy but also about human nature.

This book was stitched together in the late 1970s, after Le Guin had achieved fame in science fiction circles even though, as she admits, when she began writing she didn’t realize that was what she was writing. This volume was not compiled by Le Guin herself, and I think a collection compiled by her would have been a bit more elegant and probably more like a unified whole than this one feels. The essays included are articles from various sci-fi magazines and journals, texts of speeches at awards ceremonies or conventions, and introductions to books. Many are Le Guin writing about the craft of writing and the field of genre fiction. The essays are divided by the editor into five sections that beyond the first (autobiographical sketch) seem a bit arbitrary, and the introductions to each section add little to the collection. A concluding bibliography of Le Guin’s work is of course now quite outdated.

But the best editor in the world could have done something similar, and anything beyond Le Guin’s own words would still have seemed like bric-a-brac or needless window dressing. Because the essays themselves make this gem among my greatest used book sale finds so far. Le Guin brings the self-critical eye of an artist and the heart and mind of a literary humanist to her explorations of her own work. Along the way she says things about the nature of narrative and of truth that resonate deeply and probably help explain why many readers have assumed she was a Christian author, though she has never claimed to be one.

It would be pointless to try to summarize the contents of this volume, which is already well thumbed and underlined and will probably sit on my shelf for frequent consulting from here on out. Instead, I offer a selection of some of the powerful quotes in this work centered around some of the philosophical aspects of her approach to writing.

For Le Guin, writing is an active and deeply spiritual response to the universe:

What science, from physics and astronomy to history and psychology, has given us is the open universe: a cosmos that is not a simple, fixed hierarchy, but an immensely complex process in time. All the doors stand open, from the prehuman past through the incredible present to the terrible and hopeful future. All connections are possible. All alternatives are thinkable. It is not a comfortable, reassuring place. It’s a very large house, a very drafty house. But it’s the house we live in. (206)

Throughout her essays, she critiques the commoditization of literature and rebukes our participation in this as readers, arguing for a higher view of writing:

If art is seen as sport, without moral significance, or if it is seen as self-expression, without rational significance, or if it is seen as a marketable commodity, without social significance, then anything goes… But if art is seen as having moral, intellectual, and social content, if real statement is considered possible, then, on the artist’s side, self-discipline becomes a major element of creation. (214)

We writers fail to write seriously, because we’re afraid — for good cause — that it won’t sell. And as readers we fail to discriminate; we accept passively what is for sale in the marketplace; we buy it, read it, and forget it. We are mere “viewers” and “consumers,” not readers at all. Reading is not a passive reaction, but an action, involving the mind, the emotions, and the will. To accept trashy books because they are “best-sellers’ is the same thing as accepting adulterated food, ill-made machines, corrupt government, and military and corporate tyranny, and praising them, and calling them the American Way of Life or the American Dream. (220)

She often feels the need to defend the genre of science fiction and fantasy against the charge that it is escapist literature:

Fake realism is the escapist literature of our time. And probably the ultimate escapist reading is that masterpiece of total unreality, the daily stock market report. (42)

That is escapism, that posing evil as a “problem,” instead of what it is: all the pain and suffering and waste and loss and injustice we will meet all our lives long, and must face and cope with over and over and over, and admit, and live with, in order to live human lives at all. (69)

Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? The money-lenders, the knownothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can. (204)

Finally, and perhaps most powerfully to me, what struck me in this collection was the way Le Guin discusses the nature of narrative itself:

We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel— or have done and thought and felt; or might do and think and feel— is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become. A person who had never known another human being could not be introspective any more than a terrier can, or a horse; he might (improbably) keep himself alive, but he could not know anything about himself, no matter how long he lived with himself. And a person who had never listened to nor read a tale or myth or parable or story, would remain ignorant of his own emotional and spiritual heights and depths, would not know quite fully what it is to be human. For the story— from Rumpelstiltskin to War and Peace— is one of the basic tools invented by the mind of man, for the purpose of gaining understanding. There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories. (31)

It is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope. (58)

What good are all the objects in the universe, if there is no subject?.. All I know is that we are here, and that we are aware of the fact, and that it behooves us to be aware — to pay heed… If we stop looking, the world goes blind. (116)

Stephen Case has published fiction at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, and Daily Science Fiction. His reviews have appeared at Fiction Vortex and Strange Horizons, as well as his own blog, stephenreidcase.com. His last review for us was Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones.

“From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” taught me the importance of Style in the writing of Fantasy, something that Ms. Le Guin marks as the identifying element of Fantasy. Or how Prof. Tolkien’s choice of Bilbo and Frodo as his protagonists puts him on par with Modernists like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce (“Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown”). Or the power of Fantasy, even when it is not of the highest quality: “Kids will devour vast amounts of garbage (and it is good for them), but they are not like adults: they have not yet learned to eat plastic.” (“Dreams Must Explain Themselves”)

The Language of the Night is my touchstone for understanding the role of morality and literature, how each molds the other. I may be due for another re-read.

Dang. Now I definitely have to read this book.

I got it as part of a paperback collection I bought on eBay back in 2013.

I’ve written up several of the books already (including the Mark Frost and the CAS). I’m still making my way through it.

“I need to read more Le Guin. […] I know her through her short stories and the Earthsea books (which I will stack up next to the Narnia books any day), but I still have not read The Left Hand of Darkness or her other important science fiction works.”

Describes me to a T as well.

I also own Language of the Night, and should really read it cover-to-cover. I don’t agree with everything she says in Elfland to Poughkeepsie, but even when I disagree, I do so because she’s made me think about something.

I read the Earthsea books to my daughters over 40 years ago, and bought them as an English teacher. Leguin has been a recurrent presence in my life since then, and I think I have now read almost all the fiction, some of it several times. More recently I’ve been drawn into her interest in the Tao Te Ching. Most recently, I came on a chance reference to The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, which I now have a copy of, and my visit here today is in the course of looking online about her non-fiction writing.

My impression is that she remains a somewhat under-published author, given her undoubted ‘major’ standing. Second-hand copies of her books are not always easily come by, and what is actively in print is somehat patchy ?