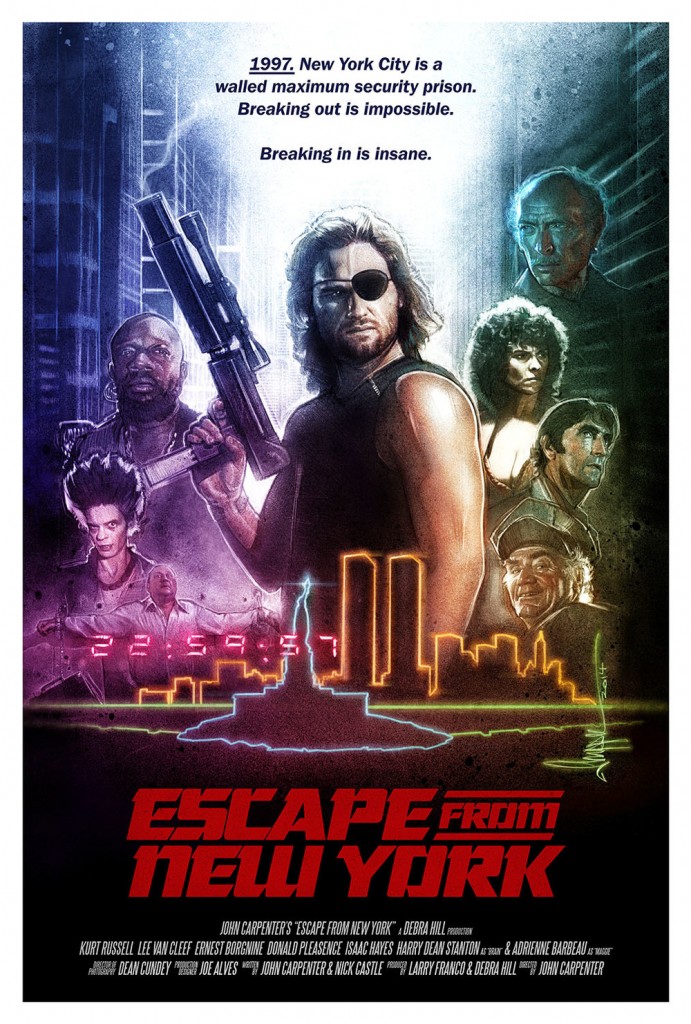

The Complete Carpenter: Escape From New York (1981)

There are no guards in this article. Only the author and the words he has typed. The rules are simple: once you go in, you do not come out … unless you click on a link or a bookmark or close the browser tab or …

Jumping out of The Fog and back into the fire as I move into the most intense period of John Carpenter’s career: the one-two knockout punch of Escape From New York and The Thing.

Escape From New York was the second movie Carpenter made under a deal with Avco Embassy. The production budget was $6 million, the largest amount of money Carpenter had yet worked with, but still tight for an ambitious SF picture. By comparison, 1981’s James Bond movie, For Your Eyes Only, had a budget of $28 million, and that was a cost-cutting move for the series after Moonraker. And the small drama On Golden Pond cost $15 million. Escape From New York ended up a hit, grossing more than four times its budget, making it one of the most successful films in Carpenter’s career — and, unfortunately, one of his few hits of his most productive decade.

The Story

In the crime-wrecked future of 1997, the island of Manhattan has been transformed into the United States’ one maximum security prison. When the US president bails from Air Force One during a hijacking, his escape pod lands in the enemy territory of Manhattan — and he has a valuable tape necessary for a looming superpowers summit. How will the US Police Force retrieve the tape (and, time permitting, the president) before the summit deadline? The solution is to task a prisoner already scheduled to be shipped into Manhattan with an extraction mission. For the job, Police Commissioner Bob Hauk (Lee Van Cleef) selects S. D. “Snake” Plissken (Kurt Russell), a former Special Ops soldier turned criminal. Snake has twenty-four hours to retrieve the president or else explosives planted in his neck will kill him. With no other choice, Snake trods through the weird wastes of Manhattan and meets its weirder denizens.

The Positives

Poised at a moment when the 1970s thriller was transforming into the 1980s action spectacle (a process that wouldn’t solidify until Commando and Rambo: First Blood Part II in 1985), Escape From New York is a culmination of the ‘70s exploitation movie archetype, the Finnegan’s Wake of the language of the Times Square Movie. It’s also a starting point of the cyberpunk dank dystopianism that still rules modern movies. Here’s where ‘70s sleaze ceased being a modern setting and became the reigning vision of a collapsed future. With the exception of Halloween, no other John Carpenter movie has exerted such an enduring influence on filmmaking.

Which is to say that there’s much to say about Escape From New York. Perhaps even more than Halloween. But the best entry point to explain why this movie sunk its hooks into people starting in 1981 is to state the obvious: Snake Plissken is freakin’ awesome.

Which is to say that there’s much to say about Escape From New York. Perhaps even more than Halloween. But the best entry point to explain why this movie sunk its hooks into people starting in 1981 is to state the obvious: Snake Plissken is freakin’ awesome.

I grew up with Kurt Russell post-Escape from New York, so I don’t recall the original Disney Boy persona that made casting him as a tough guy look like a gag. Because of what Russell has made of his career since, rolling along as a constant welcome presence in almost any movie, the casting clearly wasn’t a gimmick and Carpenter knew exactly what Russell could achieve. (They had previously worked together on the television movie Elvis). But both director and actor leaned into audience perceptions in 1981 to make Snake Plissken strike even harder as both an anti-hero and a sly smirk at the image of the terse, ambiguous Clint Eastwood and Steven McQueen tough guy. Snake is Bullitt and the Man with No Name, except the cool exterior now covers a man who truly, deeply, passionately does not give a damn.

At the core, Snake Plissken is a joke, something Carpenter, screenplay co-writer Nick Castle, and Russell know and have fun with. His name is silly. He wears tight snow camo pants, a leather jacket, and a goofy eyepatch. He whispers most of his lines as an Eastwoodian parody. He has former criminal associates named Harold and Cisco Bob. He seems to go out of his way to help nobody at all unless it benefits him. (He makes one minor effort to pull the girl in the Chock Full O’Nuts away from the zombie-like Crazies, but in a hot second pivots back to saving his own skin.)

The most important scene for Snake’s character is his meeting in Bob Hauk’s office when he’s offered the extraction mission to the prison. When Hauk first informs Snake of the situation with the president, Snake’s response is to ask laconically, “President of what?” I love that line, because it shoots to the heart of why Snake Plissken is so beloved. Russell as Snake never has to speak much to mean plenty: “A president, huh? You mean we still have one of those? And what’s that mean to me?”

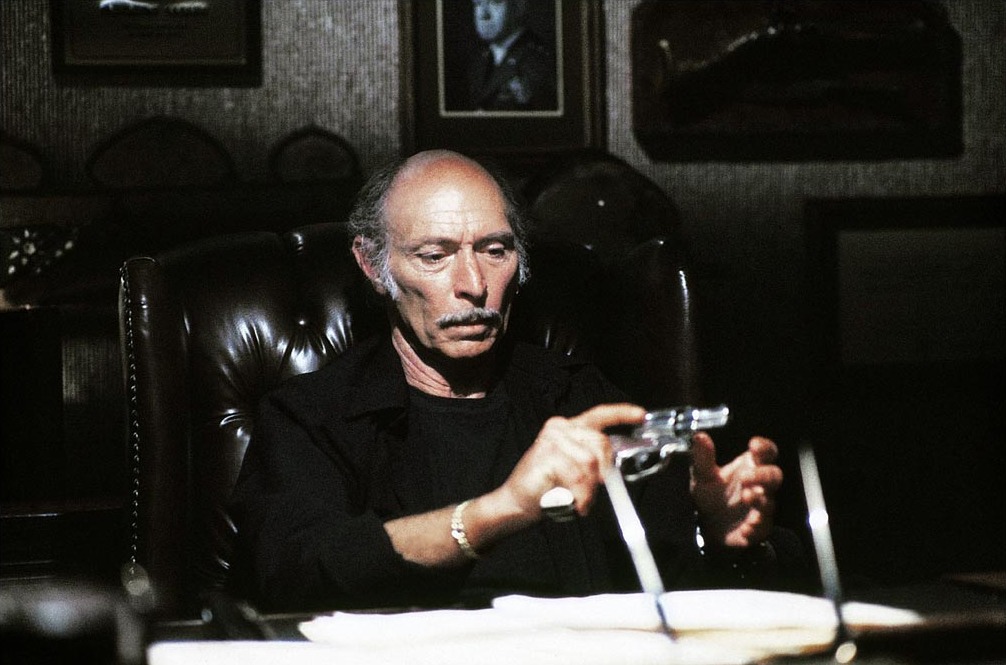

Here’s the heart of the exchange in Hauk’s office:

Hauk: I’m making you an offer.

Snake: Bulls**t!

Hauk: Straight just like I said.

Snake: I’ll think about it.

Hauk: No time. Give me an answer.

Snake: Get a new president.

Hauk: We’re still at war, Plissken. We need him alive.

Snake: I don’t give a f**k about your war — or your president.

Hauk: Is that your answer?

Snake: I’m thinking about it.

Snake Plissken doesn’t care, but he doesn’t care in an interesting way. That’s why you want to hang with him and root for him to save his own hide, and perhaps save a few other people as “collateral rescue.”

Snake Plissken doesn’t care, but he doesn’t care in an interesting way. That’s why you want to hang with him and root for him to save his own hide, and perhaps save a few other people as “collateral rescue.”

The entire office scene deserves deep analysis; it’s the calmest sequence in the movie but shoulders a hefty amount of character sketching and world building without the audience initially catching on to it. Through a few mentions of previous military action (“You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad.”) we see hints of the history behind the setting introduced in the opening text and narration.

The scene also reveals a great deal about the supporting character MVP, Lee Van Cleef’s Police Commissioner Hauk. Hauk is from a different generation than Snake and remembers the time before the country transformed into a police state. But Hauk has also gone through what Snake has, fighting in the thick of a world war. But where Snake turned into the cynical outsider, Hauk stepped into the system. He executes his part in the system with precision, but he also understands Snake. When a guard warns Hauk before Snake is brought into the office that the man is dangerous, Hauk responds tranquilly: “I know. I’ll be okay.”

Van Cleef, an actor with experience playing off a laconic anti-hero, is dead-on in the part. He’s able to convey that Hauk actually likes Snake, even when growling at him or making threats to “burn him off the wall” if he tries to dodge the mission. “We’d make one helluva team, Snake,” Hauk says with a grin at the conclusion, finally using Snake’s preferred nickname. (Snake, of course, then changes his mind about that: “The name’s Plissken.”)

I’ve spent a good chunk of space discussing the office scene, but I believe it’s that important, and I didn’t want to make this article another “Best Moments” from Escape From New York. Except I’m going to do something like that anyway, because there’s so much contributing to the film’s success.

The Rest of the Cast (‘Cuz, Wow)

The Rest of the Cast (‘Cuz, Wow)

This is the finest “Carpenter Acting Co.” film. The ensemble is formidable, starting with the people who appeared in more than one Carpenter movie: Kurt Russell, Donald Pleasence, Tom Atkins, Harry Dean Stanton, Adrienne Barbeau, Charles Cyphers, Frank Doubleday, Buck Flower, and an uncredited Jamie Lee Curtis as the narrator and prison PA system announcer. Then add one-timers Van Cleef, Ernest Borgnine, and Isaac Hayes. There’s so much talent filling up even bit parts that it would require an entire post to explore them. The short version is everyone is on-point with unique characters and interpretations.

Donald Pleasence as the president (of what?) ends up a major surprise. Not a surprise that he’s good in the role — come on, look who we’re talking about. It’s the lengths Pleasance is willing to go in the finale when the president, supposedly the normie trapped among the weirdies, turns into the darkest figure in the whole damn movie. He rains bullets down on the Duke of New York (Isaac Hayes) while screaming maniacally, finally letting out an exhausted echo of the Duke’s braggart mantra: “You’re — “A” — Number — one.” This feral wrath even stuns Snake, and it’s a reason he makes his final decision about what the rest of the world can do with itself, starting with the president. Pleasance turns transcendent and leaves a lasting image.

A special commendation to Frank Doubleday as the Duke’s goon Romero, who appears to have hopped a plane from Australia after completing filming of The Road Warrior and never changed his costume or makeup. Even among the rest of the New York assembly of the bizarre, this fellow exists on another planet. Doubleday’s acting decisions make no sense and I love that.

The World of the Prison (And Beyond)

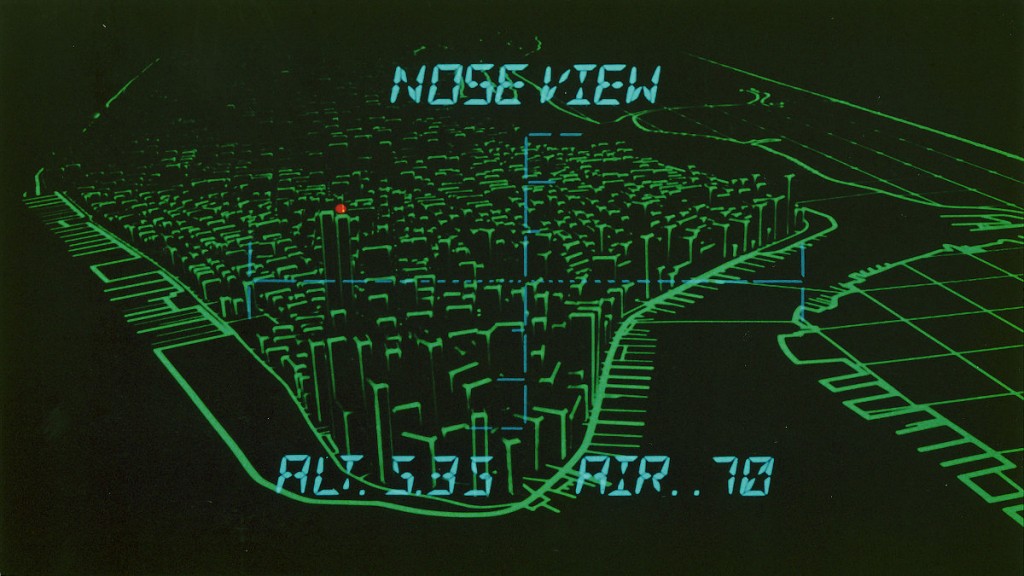

The office scene is only one place where Escape From New York crafts an immersive world on a budget. The opening narration and graphics are as effective a shorthand as the Star Wars text crawl at setting up the story with maximum clarity and minimum boring exposition. The orientation before Snake is launched into the prison prepares audiences for the culture behind the walls, with the Crazies in control of the underground and generators and cars running from fuel coming from an unknown source.

Once Snake enters Manhattan, the world becomes deep and wide. The visuals are essential here, and once more cinematographer Dean Cundey earns his reputation as Carpenter’s most important collaborator. The production design by Joe Alves is also a thing of brutal beauty, turning a burned out section of St. Louis into the canyons of a dark NY fantasy world. The drive down Broadway, which is now a gauntlet of people who simply attack anything that comes along, is a perfect nightmare.

Once Snake enters Manhattan, the world becomes deep and wide. The visuals are essential here, and once more cinematographer Dean Cundey earns his reputation as Carpenter’s most important collaborator. The production design by Joe Alves is also a thing of brutal beauty, turning a burned out section of St. Louis into the canyons of a dark NY fantasy world. The drive down Broadway, which is now a gauntlet of people who simply attack anything that comes along, is a perfect nightmare.

Each of the characters Snake meets along his journey creates the aura of a larger story behind them. How did the relationship between Brain (Harry Dean Stanton) and Maggie (Adrienne Barbeau) start? Who was the Duke of New York (Isaac Hayes) before he was shipped to Manhattan, and how did he become the biggest criminal among a world of criminals? In a movie like this, these are the question you want to be asking afterwards.

The character whose backstory intrigues me the most is Cabbie (Ernest Borgnine). Cabbie still dresses in the prototypical New York cab driver’s outfit, and he insists he’s been driving his cab for thirty years. If true, this means Cabbie lived in the old Manhattan and decided to remain when the city was turned into a prison. When we first see Cabbie, he’s bobbing his head along to the music of a drag show that’s trying to replicate a Broadway performance. That the show exists, and Cabbie exists, says Manhattan has hangers-on from the olden days who’re trying to locate the magic of the Big Apple they remember in the rotten apple core of the present.

Time and Pacing

We have a literal ticking clock for this movie, displayed on Snake’s wrist readout: the time until Snake dies from his arteries blowing open and the tape in the president’s briefcase becomes useless — as does the president. However, having a literal ticking clock doesn’t mean a film will be suspenseful; for a lesser movie it can be an artificial crutch to cover up poor storytelling. Carpenter and Co. work the time limit for tension by ensuring the audience always knows how time is slipping away and then pacing the action to match.

Part of effectively using time is also allowing it to slow down occasionally. Escape From New York is willing to let Snake, our action hero, pull up a chair at one point and wait for something to happen. It’s a strange moment for this type of film, and it’s hard to imagine a movie today letting the hero just take a break. But Snake’s pessimistic sit-down is the prelude to the slow appearance of the Crazies and the start of their rampage.

The finale, a chase across the 69th Street Bridge and the last crawl up the wall, is where Carpenter pays off the build of suspense. The editing, music, performances, blocking … everything goes full white-knuckle. It’s some of tightest filmmaking in the director’s career.

The Music

The Music

Most Carpenter fans would vote the score for Escape From New York as the best to any Carpenter project. I won’t go that far; I have a personal preference for the hard hitting simplicity of Assault on Precinct 13’s score. But no question, the music here is spectacular, strange, and fits the movie like tight snow camo pants. This was the first time Carpenter worked with co-composer Alan Howarth, which would prove almost as important a collaboration as that with Dean Cundey. The main title is iconic and as attached to the name “John Carpenter” as the theme for Halloween. But there’s a variety of styles and techniques at work. Listening to the soundtrack album on its own feels like a Greatest Hits compilation from a non-existent band.

There are plenty of fantastic cues to point out; I’ve already mentioned how the music ratchets up the finale, and the parody Broadway show tune “Everyone’s Coming to New York” is a riot. But the major stand-out for me is what Howarth and Carpenter do with Debussy’s piano composition “La cathédrale engloutie” (“The Sunken Cathedral”). The electronic realization is ethereal and lovely on its own, but it’s where it appears that stuns: Snake flying the Gullfire into Manhattan. The score at this point “should” be dramatic, tense, maybe propulsive. But instead, the music paints the sequence as mysterious and beautiful — and damn, it works. Like almost everything in Escape From New York, it’s weird but perfect.

The Negatives

Given the how well the movie paces the ticking clock so the audience remains aware of the deadline and its approach, the use of daylight is a mite bit confusing. With a 24-hour time period starting at 8:45 p.m., there’s going to be a significant stretch of daylight. But daylight isn’t appropriate for the mood and would make it difficult to maintain the illusion of New York’s ruined urban landscape. So the movie skates through the daytime as fast as possible, keeping Snake imprisoned by the Duke and trapped indoors. Then, in the space of one cut as Snake makes it back to the Gullfire on the World Trade Center, pitch black night abruptly falls. This is a minor criticism, but it’s the rare spot where I feel tugged out of an otherwise immersive film.

The Pessimistic Carpenter Ending

Snake switches the valuable tape so the president (of what?) ends up playing “Bandstand Boogie” from American Bandstand to the Hartford Summit rather than the planet-saving nuclear fusion data. Snake destroys the real tape, because seriously the hell with all of you.

Next: The Thing

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Great rundown of the movie! Thanks for the fun read.

As a McGuffin, I think the tape was a bit of a weak point. Whatever info is on it, it can’t be the only copy of that info in the world. Through my first watch of the movie I assumed they wanted the tape back so that the secret info on it didn’t get out… but in the end it turns out that the president is on his way to make the contents of the tape available to his opposite number(s) anyway. The switch-up is a funny bit, but it’s more of a poke in the ribs than a punch to the face. On the other hand, maybe that’s exactly what’s needed.

It’s not like the movie isn’t a great one, though–endlessly rewatchable.

James, my own head-canon is that playing “Bandstand Boogie” actually saved the world. Everyone at Hartford started dancing, because what a great tune! And so there was peace once again. (Until the earthquake struck Los Angeles.)

Stealing that for my next rewatch.

A few years ago, my wife and I were driving through Baltimore, to drop someone off in the crappy part of town (which would probably describe most of it). Late at night. There was no power *at all* in the section we were driving through – just pure darkness – and we couldn’t quite figure out how to get back to the highway, but I saw a cop parked on the roadside, so I pulled alongside to ask him. The cop very gravely says to me, “Go that way. DO NOT STOP FOR ANY REASON, not even stop signs, let no one approach you.” All I kept thinking was, “I’m driving through Escape From New York…” – it was that dead and creepy.

I love the soundtrack especially during the whole bridge sequence. Most action movies would have a bombastic feel during that, but it’s still relatively understated and downbeat even when Snake is kicking the Duke’s ass. I don’t know it just works. And the Duke’s car with the chandeliers on the hood is one of my all-time favorite movie cars.