The Rationality of the Monstrous: Fourscore Phantasmagores

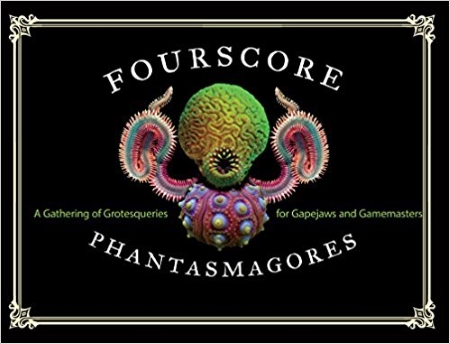

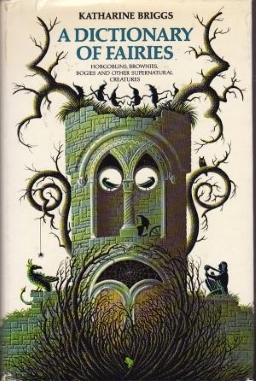

There’s a paradox in the nature of a dictionary of monsters. The medieval bestiaries at least claimed to be compendia of actual knowledge. But books like Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero’s Book of Imaginary Beings (Manual de zoología fantástica) and perhaps even Katharine Briggs’ Dictionary of Fairies are only superficially rational collections of information. Though alphabetised and cross-referenced, the logical framework’s a way of presenting wild fantasy and dream: basilisks and baldanders, brownies and banshees, sylphs and sphinxes. The Monster Manual, and the role-playing handbooks it inspired, take this contradiction to a new level — detailed statistics for each creature described along with the avowed intent of inspiring new stories featuring the legendary or imaginary entities. Quantified, numerically precise, the monsters in these enchiridia still crack open the inside of the head, driving readers to imagine worlds big enough to hold dungeon-dwellers and dragons. Rupert Bottenberg’s Fourscore Phantasmagores is the newest volume of these wonders for gamers and monster-lovers of all stripes, presenting, as it says on the cover, “A Gathering of Grotequeries for Gapejaws and Gamemasters.” And, conscious of its predecessors, the book’s a rich source of inspiration; a grimoire seeding new myths.

There’s a paradox in the nature of a dictionary of monsters. The medieval bestiaries at least claimed to be compendia of actual knowledge. But books like Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero’s Book of Imaginary Beings (Manual de zoología fantástica) and perhaps even Katharine Briggs’ Dictionary of Fairies are only superficially rational collections of information. Though alphabetised and cross-referenced, the logical framework’s a way of presenting wild fantasy and dream: basilisks and baldanders, brownies and banshees, sylphs and sphinxes. The Monster Manual, and the role-playing handbooks it inspired, take this contradiction to a new level — detailed statistics for each creature described along with the avowed intent of inspiring new stories featuring the legendary or imaginary entities. Quantified, numerically precise, the monsters in these enchiridia still crack open the inside of the head, driving readers to imagine worlds big enough to hold dungeon-dwellers and dragons. Rupert Bottenberg’s Fourscore Phantasmagores is the newest volume of these wonders for gamers and monster-lovers of all stripes, presenting, as it says on the cover, “A Gathering of Grotequeries for Gapejaws and Gamemasters.” And, conscious of its predecessors, the book’s a rich source of inspiration; a grimoire seeding new myths.

Published by ChiZine Publications’ imprint ChiGraphic, Phantasmagores mixes words and pictures, all from Bottenberg, into 80 different monstrous imaginings. (In the interests of full disclosure I’ll note that I know Bottenberg through his work as director of the animation section at the Fantasia International Film Festival; well enough that I wouldn’t normally call him by his last name, but such are the conventions of criticism.) A foreword by Ian C. Esselmont and introduction by Bottenberg help establish the precedents and aim of the book: this is explicitly a collection of creatures for use in role-playing games, even though it can be read as illustrated prose poetry. Each of the monsters gets a full-page full-colour image; brief and often ironic notes on its type, size, habitat, traits, and attacks; and a paragraph of allusive descriptive text. There are virtually no numbers, and nothing system-specific, but enough information to get the essence of each creature across. Which is to say: there’s enough detail to work with, enough that individual gamemasters can work up stats and campaign-related specifics as needed. The book’s success lies not just in the cleverness and craft of its language and art, but in the precision with which it implies more than it says, spurring readers to imagine even more. You don’t need to be a gamer to enjoy this book — but you’ll get practical use out of it if you are.

It’s worth starting with some consideration of how Phantasmagores serves its purpose as a gaming handbook. Bottenberg understands, I think, that the principal aim of the early D&D handbooks (and perhaps even modules) was to inspire gamemasters and players to create their own stories, not to present a story for them to play out. So the descriptions here aren’t definitive or encyclopedic; they work to open up story possibilities rather than close them off. You understand what a creature is, what role it serves in a fictional world, and how it can be presented in a story — what sort of emotional texture it should evoke, whether dread or awe or wonder. Thus one is amused by the abodient, a massive turtle with a house upon its back suitable for wizards or peddlers of miscellaneous magical items; chilled by the miasmagon, a practitioner of a black surgical art who wields the fearsome ventiplume to extract bodily humours; and awed by the harkestiel, the dwarf cosmovore, and the devastriant.

It’s worth starting with some consideration of how Phantasmagores serves its purpose as a gaming handbook. Bottenberg understands, I think, that the principal aim of the early D&D handbooks (and perhaps even modules) was to inspire gamemasters and players to create their own stories, not to present a story for them to play out. So the descriptions here aren’t definitive or encyclopedic; they work to open up story possibilities rather than close them off. You understand what a creature is, what role it serves in a fictional world, and how it can be presented in a story — what sort of emotional texture it should evoke, whether dread or awe or wonder. Thus one is amused by the abodient, a massive turtle with a house upon its back suitable for wizards or peddlers of miscellaneous magical items; chilled by the miasmagon, a practitioner of a black surgical art who wields the fearsome ventiplume to extract bodily humours; and awed by the harkestiel, the dwarf cosmovore, and the devastriant.

That range to the emotional texture of the book is crucial not just to its overall effect on readers (gamers and non-gamers alike), but to the way it successfully evokes the mood of old-school gaming supplements. Gary Gygax had a very specific prose style, which reached back to the elaborate language of early fantasy writers as a way to present rules for simulating pulp fantasy narratives; it also evoked the varied attitudes of those writers, ironic and visionary and learned and blood-curdling by turns. Much early D&D writing followed his lead. Bottenberg doesn’t try to emulate Gygax, or any of the other TSR writers, but does use highly-crafted language: alliteration, recherché vocabulary, rhythmic sentence structure, and the occasional well-placed pun. At best, the linguistic play of the book echoes prose-poet fantasists like Clark Ashton Smith or Jack Vance. If this is witty, it’s also wit making things new. It’s playful, just as it aspires to be full of play.

At the same time, Bottenberg draws practical connections between his monsters — not necessarily making a detailed setting, but, as in any collection of RPG monsters, implying ecologies and showing how different creatures fit together. How the myths overlap and play off each other. So a “spectral sorceress” called a chromatriarch, who is “prone to the use of colourful language,” has a familiar called a prismite (described separately), and uses crystals taken from other monsters called coruscatasens (again, described elsewhere in the book). Wordplay meets worldbuilding: the mystery of language is that monsters are made by combining words. That’s true of other monster books, of course, but I find the diction here more central and more evocative.

Similarly, Bottenberg’s visuals are varied but always striking, illustrating the characters of his entities while also presenting attractive images. He uses a range of media, including sculpture, computer graphics, and several styles of pen and ink drawings. Some of the pictures are realistic, some abstract in a literally iconic way (as the harkestiel or the enantiope), but all of them present creatures full of personality, living beings ready to step into story. Bottenberg’s colour sense is perhaps the most consistent and impressive aspect, everything here bright and bold.

Similarly, Bottenberg’s visuals are varied but always striking, illustrating the characters of his entities while also presenting attractive images. He uses a range of media, including sculpture, computer graphics, and several styles of pen and ink drawings. Some of the pictures are realistic, some abstract in a literally iconic way (as the harkestiel or the enantiope), but all of them present creatures full of personality, living beings ready to step into story. Bottenberg’s colour sense is perhaps the most consistent and impressive aspect, everything here bright and bold.

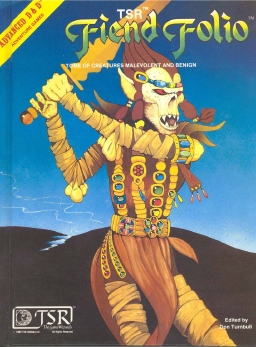

The result is a volume that evokes the sense of classic D&D texts without being derivative. A similar sense of wonder is created through similar means. It’s interesting that both Esslemont and Bottenberg mention the Fiend Folio in their introductory texts, with Bottenberg singling it out for special praise as “magnificent” and “innovative.” The Folio was less indebted to traditional legends than the Monster Manual, and perhaps had a different sensibility beyond that: largely drawn from monsters first published in the British White Dwarf magazine, it couldn’t help but be more idiosyncratic than the foundation the Monster Manual provided. But it also had monsters from a larger pool of creators, and more artists providing interior illustrations: more styles, perhaps more of the sense of an anthology. (I’ll note that the dramatic Emmanuel-drawn cover, featuring the Charles Stross–created Githyanki, strikes me as closer to the visual tone of Fourscore Phantasmagores than either of the first Monster Manual covers.)

Although the production of one author, Phantasmagores has the unpredictability of the Fiend Folio paired with the tongue-in-cheek scholasticism of the Monster Manual text. The effect is of a decadent pedant, using the resources of a far-flung vocabulary and a knack for understatement and implication to describe the essence of monstrosity. The book’s aware that to describe a monster in full detail is to remove the joy of playing with it, and of learning about it by taking on its role (as gamemasters must). Its own specific form of poetry, the carefully-chosen words of the entries give us what we need and no more.

The monsters rarely derive from the legends of any specific culture, though some seem to nod to European lore (like the pluckie or the drahml), and I suppose it’s possible to argue that the way the creatures seem derived from the play of English words and their roots links them to English or European settings. But their depictions are general enough that I’d think many if not all could be repurposed to fit any fantasy milieu. Similarly, most of the monsters are described in gender-neutral terms, either as “it,” or, in the case of humanlike creatures, “his or her.” The exceptions are a few monsters who are always of a particular gender — more often female (like the chromatriarch or the frenesiere), but occasionally male (brutaliator and implicitly the stag-like enantiope), while the devastriant is an androgyne. In general, the book’s almost exactly as open and as restrained as the old D&D books in presenting sex. So there’s occasional toplessness in the illustrations, but the descriptions opt for hints over details, and get no racier than the crop-wielding sprite called the nefaryad:

The monsters rarely derive from the legends of any specific culture, though some seem to nod to European lore (like the pluckie or the drahml), and I suppose it’s possible to argue that the way the creatures seem derived from the play of English words and their roots links them to English or European settings. But their depictions are general enough that I’d think many if not all could be repurposed to fit any fantasy milieu. Similarly, most of the monsters are described in gender-neutral terms, either as “it,” or, in the case of humanlike creatures, “his or her.” The exceptions are a few monsters who are always of a particular gender — more often female (like the chromatriarch or the frenesiere), but occasionally male (brutaliator and implicitly the stag-like enantiope), while the devastriant is an androgyne. In general, the book’s almost exactly as open and as restrained as the old D&D books in presenting sex. So there’s occasional toplessness in the illustrations, but the descriptions opt for hints over details, and get no racier than the crop-wielding sprite called the nefaryad:

The loveliest rose still has its thorns, and likewise does the faerie realm include this dark and malicious sorority, acting as a counterweight to its beneficence. Indeed, the nefaryad perverts and corrupts the natural ways of the faerie — tenderness becomes torment, charm becomes chastisement, caprice becomes chaos. Her contempt for all creatures of the masculine gender inspires her devious acts of trickery, vexation, and emasculation.

I don’t see any themes common to all eighty entries, beyond the play with language — although starting the volume with the “cosmic confabulator[s]” called the Aam does seem relevant to Phantasmagores’ self-definition. Overall, I think the book plays about with three distinct tones: a folkloric take on the natural world; a weird fantasy nodding to the more outré entries in the Dungeon Master’s Guide’s Appendix N; and, occasionally, a Kirbyesque sense of cosmic wonder. Some creatures lean more to one of these aspects or another, but they all work together with the cleverness of language to create a sense of variety in unity. Few of these monsters feel like things you’d find in another gaming supplement. There’s a distinctive voice to the book, which if it does not create a world at least populates one.

All these monsters; eighty of them, not counting creatures mentioned in passing but left undescribed, like megatritons and mutilatrices. I wonder if the secret of creating a truly successful monster handbook is simply to be fascinated by the monstrous. To have sympathy for the inhuman. At last year’s Fantasia Festival Guillermo del Toro spoke passionately about his love for monsters, his view of Frankenstein’s Monster as a holy figure, and how he always cared for the monsters in a story much more than for the human characters or for humanity as a whole: the monster, the unreal entity, is then not necessarily always an other, but can be a figure with whom we identify.

All these monsters; eighty of them, not counting creatures mentioned in passing but left undescribed, like megatritons and mutilatrices. I wonder if the secret of creating a truly successful monster handbook is simply to be fascinated by the monstrous. To have sympathy for the inhuman. At last year’s Fantasia Festival Guillermo del Toro spoke passionately about his love for monsters, his view of Frankenstein’s Monster as a holy figure, and how he always cared for the monsters in a story much more than for the human characters or for humanity as a whole: the monster, the unreal entity, is then not necessarily always an other, but can be a figure with whom we identify.

Perhaps this is because monsters can be the key to story. If unreal, then they come out of dreams, or the same mental processes that create dreams — the leap of logic, the moment of double vision. The word deformed to make a name for a new thing: language breeds monsters in the mind. A fantasy role-playing game’s a collective story about an encounter with the monstrous, with the things that lurk in the subconscious. Fourscore Phantasmagores presents a crowd of phantoms from the underworld of the psyche fit for heroes to encounter, for their bedevilment, bafflement, or occasional bludgeoning. It’s a wonderful book in itself, and an inspiring collection of seeds for sagas to come.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Love the sound of this. It sounds similar to Fire on the Velvet Horizon by Patrick Stuart, which was one of my favourite books of last year so if its anywhere as inventive as that then it will be worth my time.