I Became a Science Fiction Fan at Exactly the Right Time: The Sixties

I’m convinced I became a science fiction fan at exactly the right time, the 60s. That was just long enough ago that there was so little science fiction (compared to now), that a young fan had to read the “classics” because there wasn’t the flood of new stuff appearing each month.

I don’t know how, exactly, I started reading E.E. Doc Smith, for example. His books originally appeared in the 30s and 40s. I bought the Skylark and Lensmen books in paperback, though, so they were still being reprinted. I read all of Edgar Rice Burroughs, also a writer who started in the early 1900s. Both the Tarzan and Barsoom stories started in 1912. Yet in the early 60s, the books were still coming out in reprints (with really cool covers).

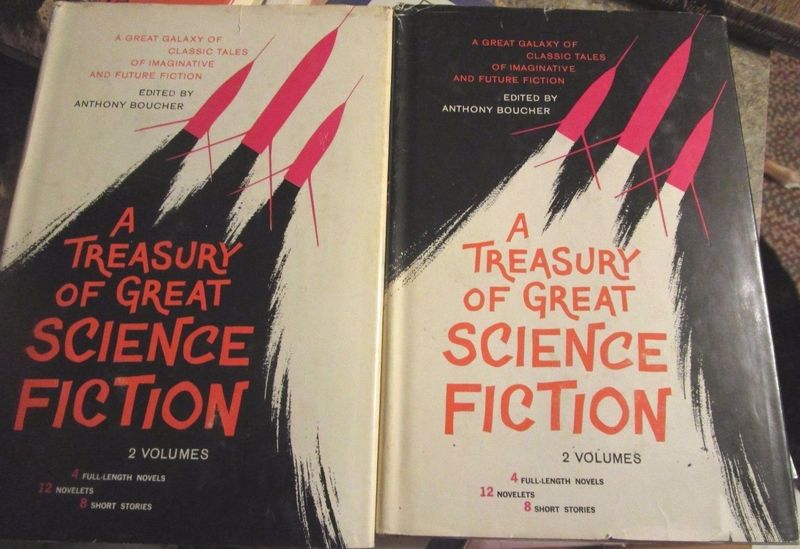

I read H.G. Wells and Jules Verne because they were among the relatively few science fiction choices in our public library. At this time, I read science fiction exclusively. I read Edgar Allan Poe, Ambrose Bierce and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle because they scratched the science fiction itch without always exactly being science fiction. I didn’t discover H. Rider Haggard and Robert E. Howard until later. I also joined the Science Fiction Book Club in the 60s. One of my first purchases was the double-volume A Treasury of Great Science Fiction, edited by Anthony Boucher and published in 1959 (I bought it because it counted as a single choice–I think it’s possible that part of my love for short fiction started with that awesome collection).

Of course, I cut my teeth on Heinlein, Asimov, Clarke, Le Guin, and Silverberg, because that was what was available. Zenna Henderson started publishing in the sixties. Her “The People” stories changed the trajectory of my life.

|

|

|

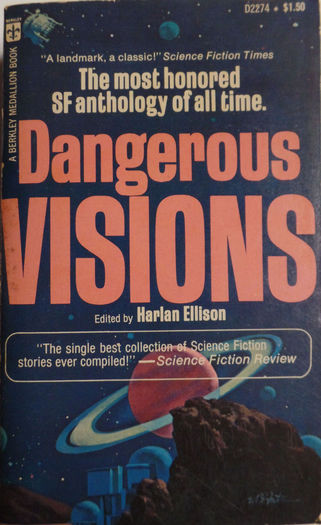

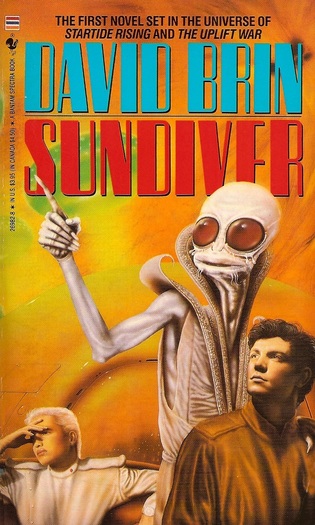

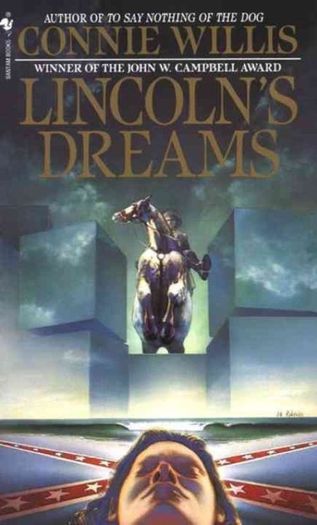

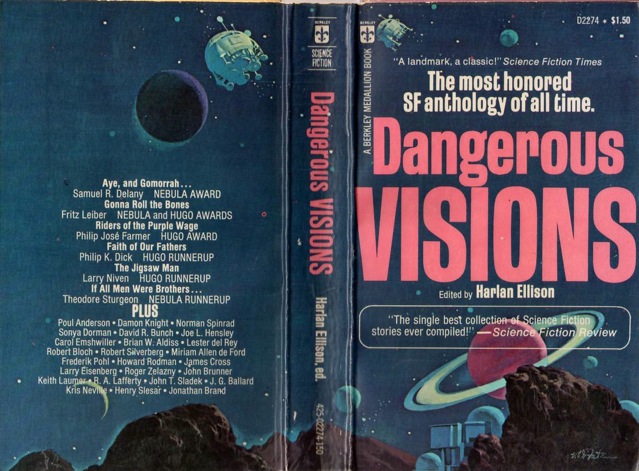

Being a fan starting in the 60s means that I was there for so many of the significant moments in science fiction. I read Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions, David Brin’s Sundiver and Connie Willis’s Lincoln’s Dreams along with a ton of other influential and now classic works, when they came out in the 60s, 70s and 80s. I read The Moon is a Harsh Mistress the month it came out. And I was in the theater the opening week for The Time Machine, 2001 a Space Odyssey, Planet of the Apes, Mad Max, Star Wars, and a bunch of others. Late night television (and Saturday morning too, sometimes) played the great, and not so great, science fiction of the 50s, so I also saw The Day the Earth Stood Still, When Worlds Collide, Them, Forbidden Planet, War of the Worlds, all the Godzilla movies, and a host of others at a time in my life when they could still shape my life.

I read on Facebook today about how young science fiction fans often have no sense of the field’s history. This is true! But to have that kind of breadth, a young fan today would have to become a scholar of science fiction. I don’t think that would be the same at all as having lived through it.

I don’t claim anything like the encyclopedic knowledge of the history of science fiction that people like Gardner Dozois, Gordon Van Gelder and many other folks who not only lived through a great deal of science fiction’s explosive years, but also shaped it. However I am glad that I was there to see it happen.

The 60s was a great place to start as a fan.

James Van Pelt’s short fiction has been published in Talebones, Realms of Fantasy, Analog, Asimov’s, Weird Tales, SCIFI.COM, and many anthologies. His collections include Strangers and Beggars (2002), The Last of the O-Forms & Other Stories (2005), and The Radio Magician and Other Stories (2009). He has published two novels: Summer of the Apocalypse (2006) and Pandora’s Gun (2015).

I say amen, brother, and again I say, amen!

I got my SF start in middle school; I would take my lunch money and visit a thrift store that was just around the corner and buy two or three SF paperbacks from their huge selection (this was in 1972-73). Heinlein, Asimov, Ballard, Clarke, Burroughs, Blish, Davidson, Ellison, Herbert, Bradbury, Sturgeon, Dick…what a foundation. It shocks me to realize how many of these aren’t even names to younger readers.

Science fiction, and fantasy too. One day in late 1966 or early 1967 I noticed a display of the Tolkien hobbit books at the public library (the Ballantine paperbacks with, I think, either the original Barbara Remington poster map or the “Come to Middle-earth!” poster). I was 11 and was already interested in sf. I was there when the first Star Trek show was broadcast in Sept. 1966. One of the first books I ever bought for myself (I think, rather than it being handed to me as a present chosen by someone else) was the Whitman Classic edition of Wells’s The War of the Worlds. Let’s not forget that American schoolkids could get sf classics through the Scholastic Book Club, delivered to their classroom. By this means I got hold not only of a bonafide classic like Doyle’s Lost World, but James Blish’s Star Trek 2, or so memory tells me.

I’ve been reading a few books that caught my eye way back then but that I didn’t read at the time and haven’t seen in ages, such as Allen Adler’s Terror on Planet Ionus. It was pretty bad, but I know I’d have found it interesting back in the day. You can read the saga of the remembering, and eventual reading, of Terror on Planet Ionus here:

https://www.sffchronicles.com/threads/549749/

Black Gate has discussed the Winston Science Fiction juveniles.

But the theme of this posting was the classics. Good topic. The public library, small as it might be, would have Wells and Verne and, probably, some Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, Heinlein, Simak, et al., and some good anthologies. But I must say that a lot of the stuff in the Galaxy Science Fiction Readers didn’t look inviting to me. Simak put me off in that so many of his short stories have amazingly drab titles (this was a problem with Asimov’s short stories, too). For a kid who couldn’t stop eyeballing Terror on Planet Ionus, those didn’t sound too interesting….

James, my story is similar to yours. I got a paper route in the spring of 1962 (I was 11 1/2) and suddenly had money to buy the things I had only been able to look at on the newsstands. I started buying “Famous Monsters of Filmland” magazine, going with a friend to the movies (“The Magic Sword,” “The Time Travelers”), picking up my first collection of H. P. Lovecraft stories, and locating a store in my downtown that stocked an incredible selection of Ace paperbacks. (I still have nearly all of those.) As a senior in high school, I discovered the SF magazines, and found a used bookstore that carried a great number of older issues of “Amazing” and “Fantastic” magazines. Five years later I attended my first Worldcon (Toronto) and got to hear Harlan Ellison read out loud, and see Isaac Asimov and Ursula Le Guin and Poul Anderson in panel discussions. At a smaller convention at Kent State in ’76 or ’77, Joe Haldeman invited a bunch of us up to his hotel room and told us Vietnam stories and how his experiences there led to his writing “The Forever War.” Just over an hour ago, I was in Columbus attending my first Marcon in almost 30 years — and only one name author was in attendance (Jacqueline Carey). I sat in on two panel discussions, and much of the talk focused on technology that didn’t even exist (except, perhaps, in SF stories!) back when you and I were cutting our teeth on the Masters. Two years ago, I taught a college science fiction class and had the best experience as a teacher in all my 31 years in front of the classroom. At the end of the semester, I typed up a list of what I considered essential SF reading, and gave a copy to each of my students. It was heavy on the good ol’ stuff, but took in some of the contemporary writers (Robt. Sawyer, China Mieville, Neal Stephenson, Ann Leckie). And I agree with Mr. Parker: it’s shocking how 90% of my list would be unfamiliar to most of today’s readers and fans. There’s so much out there that’s 20, 30, 40, 50 and more years old, that still holds up today. My 23-year-old daughter was in that class, and still talks about how much she enjoyed Haldeman’s novel, but also Alfred Bester’s “The Demolished Man” and Clarke’s “Childhood’s End.” The kids need that exposure to the classic works, and us older folks need to see that they get it.

Awesome James! Became a fan in the 70s, so we’re offset a year. Explains where you get your Muse and my enjoyment of your work. Keep on reading and creating

Meant offset a decade

I have that set of TREASURY OF GREAT SCIENCE FICTION. It’s a great bunch of stories. I started reading SF in the 50s, so before you, but my interest is similar. I started with ASTOUNDING SF mostly, so those were the authors, along with the big three and several others, and Howard and Fritz Leiber, plus other fantasy. I considered the Fifties the perfect time to be a new fan, so we all have our viewpoint.

HI, Major. I was such a science fiction fanatic that I wouldn’t read fantasy at all. I remember trying to read The Hobbit in junior high and being thrown off by all the weird names. It wasn’t until I was in college in the early 70s that I picked up a paperback edition of The Fellowship of the Rings that someone had left in the student union. I missed several days of classes as I read it and then the next two books. I became a fantasy fan too after that.

I read War of the Worlds at my grandmother’s house when I was ten or so. She had a bookshelf filled with the Reader’s Digest condensed versions of classic novels. I had tripod nightmares for years afterwards. Of course, I loved the book.

Hi, Smitty. I knew nothing about fandom and conventions until 1996, when I was 42. You’d think that I would know about them since I was reading Analog and other science fiction magazines. They often announced upcoming conventions, but I skipped those sections, and it never occurred to me that a convention was something I could go to.

In fact, most of my young science fiction reading life was in isolation. No one I knew read the books I read, so I couldn’t discuss them with anyone. Even my Dad, who loved science fiction movies, didn’t read the books. I remember a girl in 6th grade who also read the Doc Savage books. We’d talk about those, but she didn’t go to the high school I went to, so I was alone again.

What finally got me to go to a convention was after I’d been selling stories for a while, I learned that there was a short story review magazine called Tangent. I wondered if they’d reviewed anything of mine, so I contacted the editor, Dave Truesdale. He asked if I was going to WorldCon in Anaheim in a couple weeks. I laughed and said, “Of course not. Isn’t there where nut jobs dress up like Klingons?” He said, “No . . . well, yes . . . but it’s also where writers, editors, publishers and reading fans get together. You should go.”

So I did. It was like coming home. It was the first time I was able to mingle with a bunch of other people who were familiar with the things I loved.

Hi, RK. You get no argument from me.

My reaction to reading the title of the article was, “No, that’s not right! The Sixties in the US was a bit of a dead zone for sf; it was the Fifties that were the real Golden Age.” Then, I started to read and realized that Mr. Van Pelt had done a perfect ju-jitsu move on me. Kudos, sir!

I, too, became a sf fan in the (late) 1960s, thanks to the lovely folks at the Scholastic Book Service (also became a Sherlock Holmes fan thanks to them, as well). And Major Wootton, guess what trashy pulp sci-fi novel I found recently on the shelves of a local bookstore? Yes, the “planet” Ionus (actually, a moon of Saturn!) was sending forth its Terror once more, just as I remembered it.

Actually, the Sixties was a comfortable time for starting out in sf. The Seventies, in which the New Wave broke onto American shores, was a much more fertile, if confusing, time. Reading Philip Jose Farmer’s “Riders of the Purple Wage” in Asimov’s The Hugo Winners really spun my sf literary compass around.

And fantasy had to wait a bit to penetrate my “rational” mindset, abetted by the insidious Ms. Le Guin, who snuck Earthsea stories into her The Wind’s Twelve Quarters collection and got me to buy the trilogy forthwith. Tolkien had to wait until friends were playing Dungeons and Dragons and I needed to read the “source material” to find out what was what.

Hi, Eugene. I should have mentioned Le Guin. I became a very streaky reader in the late 60s and early 70s, latching onto a writer and then reading everything by them I could find. Le Guin was one of the early ones. I also streaked through Silverbarg, Simak, Bradbury (of course!), Vonnegut, Sturgeon, Wyndham, Blish, McCaffrey, Lewis, Matheson . . . well, most of them.

I could do a long and heartfelt rift on Bradbury. The Treasury of Science Fiction may have started my love of reading short stories, but Bradbury made me want to write them.

Third and final day of Marcon 2017 today, and 2 of my 3 daughters went with me. I bought a dozen or so books yesterday & today, and one was an omnibus collection of 4 novels by A. Bertram Chandler, one of my favorites back in the ’60s when I first started buying Ace Doubles. The dealer I purchased it from asked me if I was familiar with Chandler, and I happened to mention this Black Gate article to him. He too lamented the ignorance of many younger readers of the greats, near-greats, and not-so-great-but-passables of the (essentially) post-Golden Age of SF. Most of the books I saw for sale were from the last 6-8 years, but there was one dealer who didn’t have anything much newer than Stephen Donaldson’s earliest work. I guess it’s gonna have to be up to fossils like us to champion the works of the group that dominated SF just after WW II up until about the end of the ’80s. I’ve gotten my daughters and some of my former twenty-something students on board. Maybe we can start a kind of renaissance…..

Should’ve mentioned: My oldest daughter absolutely LOVED Alfred Bester’s “The Demolished Man” and his Hall of Fame story, “Fondly Fahrenheit,” and she nearly drooled over the Cordwainer Smith we read in that SF class. Now she’s trying to coax my youngest into following suit….

Hi, Smitty. Keep fighting the good fight.

I loved the Ace Doubles. I always felt I was getting twice as much reading for my money (even though they were short novels). Reading them was also the beginning of science fiction scholarship for me. As soon as I finished the second one, I’d start comparing them. Which one was more effective? Why was it more effective? What did the weaker one do poorly? Etc.