Pellucidar Break: The Monster Men by Edgar Rice Burroughs

I’ve reached the halfway point on my retrospective of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar novels — and if I’ve learned one thing from having done two other complete ERB retrospectives (aside from never get in a flying vehicle with Carson Napier), it’s that I should take a break before plunging forward into the second half. Or maybe plunging down into the second half. Once a Burroughs series enters the late 1930s, the drop off in quality can get frightfully steep.

I’ve reached the halfway point on my retrospective of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar novels — and if I’ve learned one thing from having done two other complete ERB retrospectives (aside from never get in a flying vehicle with Carson Napier), it’s that I should take a break before plunging forward into the second half. Or maybe plunging down into the second half. Once a Burroughs series enters the late 1930s, the drop off in quality can get frightfully steep.

So before going Back to the Stone Age, I’m rewinding to the salad days of ERB’s career and exploring a lesser-known work: a take on Frankenstein and The Island of Dr. Moreau filtered through the pulp jungle adventure; a book of great promises and great frustrations.

The story that would eventually become The Monster Men is an ambitious thematic and character experiment that explodes with the exuberance of early Edgar Rice Burroughs. It’s also a misfire where generic pulp elements and a terrible ending undermines the potential for one of its author’s most intriguing works. The ebullience of youthful ERB bursts through, but the control and follow-through with complex ideas seem to have been left to the concurrent Tarzan, Mars, and Pellucidar series.

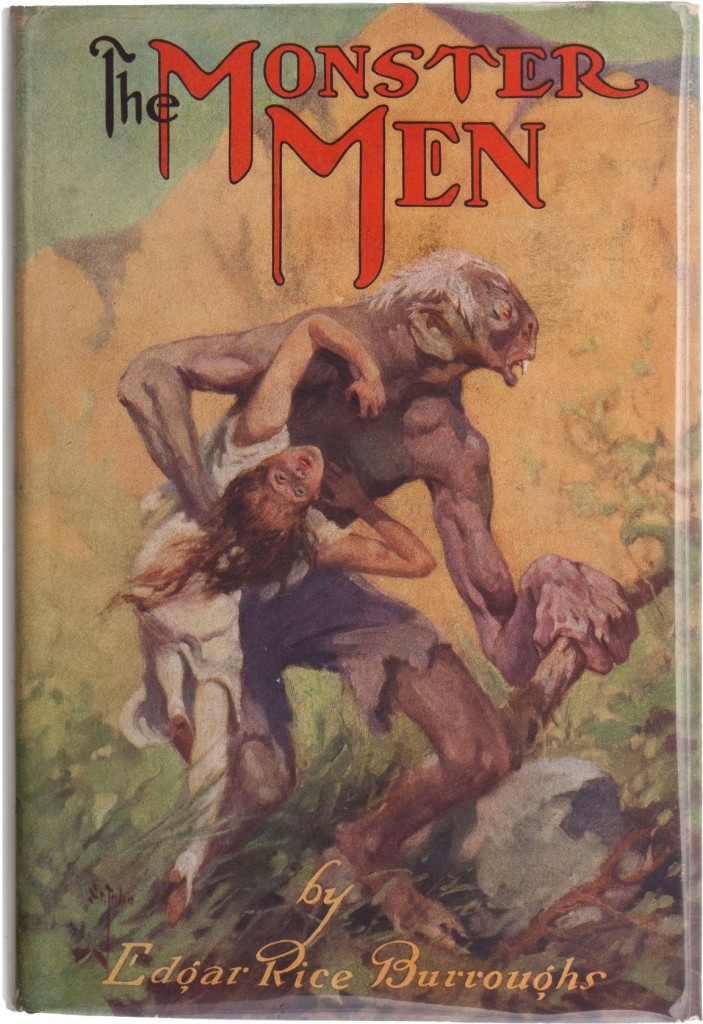

Burroughs wrote the novel in April 1913 during a feverish period between The Cave Girl and The Warlord of Mars. He may have devised the idea in late 1912 as a short story. But he soon discovered the short story wasn’t his medium and expanded the idea into a full-length book titled “Number Thirteen.” It appeared as “A Man without a Soul” in the November 1913 issue of All Story. For its first book publication in 1929, the name was changed to The Monster Men, by far the weakest of the trio of titles, but the one we’re stuck with. “The Man without a Soul” had been used as the title for the U.K. book publication of The Mucker, which probably accounts for the change. The title coincidence between these two books, however, isn’t exactly a coincidence, something I’ll examine later.

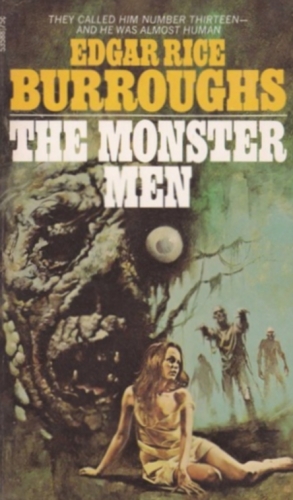

The Monster Men opens as good pulp should, on a moment of shock. Professor Arthur Maxon, an embryonic version of the Martian mad scientist Ras Thavas, is disposing of his latest failed attempt to create a perfect human through chemical means. Maxon’s nerves are jangled because the botched lifeform is human enough to look as though the doctor has committed murder. Maxon’s daughter Virginia knocks on his laboratory door, begging to see him. He tells her to go play with her dolls, and for a moment readers believe Virginia is a child and the story will follow Maxon trying to protect her from the consequences of his experiments. But Virginia Maxon is a grown woman, and within three chapters Professor Maxon will switch to maniacal mode, seeking to have his daughter wed to the perfect outcome of his experiments, whether she wishes it or not.

With the Frankenstein aspect of the story established, we head into “Doctor Moreau meets Tarzan” territory. Maxon flees the consequences of his experiments with a long sea voyage on the ship the Ithaca, then changes his mind and seeks out a Pacific Island where he can grow his chemical people in seclusion. His goal is a perfect human he will force into a marriage with Virginia. “The future of the world will be assured when once we have demonstrated the possibility of the chemical production of a perfect race,” he declares, although his fixation on using his daughter as a key part of the experiment tamps down his supposed utopian eugenics promise and makes it somehow even creepier. This predates Burroughs’s own promotion of eugenics (see Lost on Venus), and there’s no sense here that Maxon’s super-race goals are meant to be viewed as humanitarian heroism.

Maxon picks up another assistant, the young Dr. von Horn, in Singapore. Von Horn has less scientific motives for joining: he’s attracted to Virginia and wants the contents of a large chest Maxon is dragging along on the journey. The chest will turn into a distracting “Object X” that’s never interesting enough to sustain its part of the story. In a twist any modern reader will spot leagues off, the chest doesn’t contain what everyone pursuing it believes it does.

Maxon picks up another assistant, the young Dr. von Horn, in Singapore. Von Horn has less scientific motives for joining: he’s attracted to Virginia and wants the contents of a large chest Maxon is dragging along on the journey. The chest will turn into a distracting “Object X” that’s never interesting enough to sustain its part of the story. In a twist any modern reader will spot leagues off, the chest doesn’t contain what everyone pursuing it believes it does.

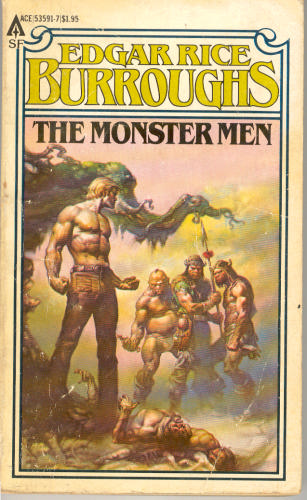

The speed of these opening chapters is typical of Burroughs, who jettisoned the long build-up common to the adventure and science fiction stories that preceded him. Within a few chapters, Maxon has created thirteen humanoids at his “court of mystery” on an isolated island near Borneo. The creatures are identified only by number, with Number Thirteen rising from the vat an outwardly perfect human specimen. The lower down the number sequence, the more hideous and bestial Number Thirteen’s brethren are.

Maxon takes Number Thirteen apart to train him to become Virginia’s eventual mate. The jealous von Horn secretly frees the other monster men, hoping they’ll murder Maxon and Number Thirteen, leaving him free to marry Virginia and inherit her wealth — and that treasure chest. Number Thirteen instead subdues the other creations and becomes their leader, adopting the name the Dyaks of Borneo call him, “Bulan.” Bulan and his attack team of vat-born brothers weave in and out of the rest of the story and the shift in action to Borneo.

The interactions between Bulan and Professor Maxon’s other creatures and Bulan’s musing on their mutual “soulless” condition is the thematic spine of the book. But for the pages attached to that spine, Burroughs relies on a rote “treasure hunt” and “kidnap the girl” scenario. Von Horn drives much of the action, simultaneously trying to obtain Virginia and the mystery chest. There’s a rotating series of secondary villains who fall in and out of the story, sometimes getting simply discarded. Bududreen, the traitorous first mate of the Ithaca, plots with the Rajah Muda Saffir to kidnap Virginia so the rajah can marry her. Although Muda Saffir sticks around for most of the novel as a principal (albeit ineffectual) adversary, Bududreen disappears during a storm and is never mentioned again.

These quick story detours and abrupt exits are scattered throughout the book, giving the sense of a more convoluted storyline than actually exists. It’s easy to find much of the plotting tiresome, and Burroughs was already writing a better version of this in the contemporary Tarzan novels. But The Monster Men is more about its characters and larger subject of the soul.

Much of the theme of what it means to have a soul rests on the muscular shoulders of Number Thirteen/Bulan. Bulan can fight with savage energy — there’s a violent battle between him and Number One, the monster man closest to being a monster — and he adopts a bullwhip as his fearsome signature weapon. But Bulan has the inner conflict of defining his humanity, specifically if he possesses a soul or not. His observation of the behavior of a man like von Horn and the actions of the other monster men gives him much to contemplate:

I am … curious as to how souls make themselves apparent. I have seen men kill one another as beasts kill. I have seen one who was cruel to those within his power, yet they were all men with souls. I have seen even soulless monsters die to save the daughter of a man whom they believed had wronged them terribly — a man with a soul. How then I am to know what attributes denote the possession of the mortal spark? How am I to know whether I possess a soul?

Bulan eventually latches onto the concept of love — his love for Virginia — as providing him a soul no matter his origins. Even if this is a “borrowed soul” he took from an external event, it still raises him above what he sees in a person such as von Horn.

The comparison between Dr. von Horn and Bulan is where the theme works best, and von Horn ends up a more complex figure than the hero (especially after the end-of-book reveal, which I’ll get to). Dr. von Horn has his eyes on almost every prize: marry Virginia, obtain the Maxon riches through inheritance, kill Number Thirteen, and seize that stupid chest. He’s the bad guy, but we spend so much time with him, meeting him in Chapter 2 and then rarely leaving his side for more than a few pages, that it’s impossible not to identify with him. He has his moments of acting as a protector toward Virginia and feels genuinely concerned for her welfare before he starts sliding toward becoming the true man without a soul. Von Horn’s journey forms an X-shaped pattern with Number Thirteen, as one becomes less human and the other more. “[Von Horn] saw that the soulless thing within was endowed with a kindlier and more noble nature than he himself possessed.”

The comparison between Dr. von Horn and Bulan is where the theme works best, and von Horn ends up a more complex figure than the hero (especially after the end-of-book reveal, which I’ll get to). Dr. von Horn has his eyes on almost every prize: marry Virginia, obtain the Maxon riches through inheritance, kill Number Thirteen, and seize that stupid chest. He’s the bad guy, but we spend so much time with him, meeting him in Chapter 2 and then rarely leaving his side for more than a few pages, that it’s impossible not to identify with him. He has his moments of acting as a protector toward Virginia and feels genuinely concerned for her welfare before he starts sliding toward becoming the true man without a soul. Von Horn’s journey forms an X-shaped pattern with Number Thirteen, as one becomes less human and the other more. “[Von Horn] saw that the soulless thing within was endowed with a kindlier and more noble nature than he himself possessed.”

Burroughs eventually dispatches von Horn in the last chapter with an offhandedness that at first appears glib — but makes sense for how sheerly pathetic it is. This is what von Horn deserved after the way he betrayed not only Virginia but also the readers by slow degrees. We and Virginia trusted him, and then he became worse than we feared he might be. A man without a soul shouldn’t make an exit with any glimmers of glory.

Not only is von Horn more interesting than Bulan, I’d rank Bulan as the book’s third best character after von Horn and Sing Lee, the cook onboard the Ithaca. Sing Lee is an authentic surprise: a Chinese character in an early pulp novel who ends up the most heroic figure in it. He’s still stuck speaking in uncomfortable pidgin English dialogue with the “r” and “l” confusion and has a stereotypical interest in traditional medicine. But he isn’t the sidekick, the comic relief, or the meaningless local color. He’s a legitimate hero and achieves almost as much in the story as Bulan. He throws himself into combat on multiple occasions to help Virginia and even kills one of the monster men to protect her. (Von Horn, the lousy sneak, takes the credit for the kill in front of Virginia.) Sing is easily the sanest and smartest person in the story, and Burroughs doesn’t treat this as unusual.

The other monster men are given poignancy, particularly as they are whittled down in the second half when fighting battle after battle beside Bulan. They eventually surrender to their belief in their own soullessness when they discover a tribe of orangutans and decide this is where they belong. When Bulan tries to dissuade them, Number Three offers a challenge: “We are not human. We have no souls. We are things. And while you, Bulan, are beautiful, yet you are as much a soulless thing as we — that much von Horn taught us well.” It’s fascinating that beauty, i.e. appearing human as Bulan understands it, is not a predictor of whether someone is human, or has a soul, or however you interpret the essential quality of humanity the book is exploring.

Most what I’ve written so far makes The Monster Men sound like a success, with only some uninspired pulpy plotting to get in its way — and pulpy anything never prevented me from recommending a work. If the novel had halted at Chapter 15, I think The Monster Men would hold a higher position in the Burroughs canon. Unfortunately, the final two chapters contain a plot twist and resolution that detonate most of the book’s themes and leave it helplessly wounded.

Most what I’ve written so far makes The Monster Men sound like a success, with only some uninspired pulpy plotting to get in its way — and pulpy anything never prevented me from recommending a work. If the novel had halted at Chapter 15, I think The Monster Men would hold a higher position in the Burroughs canon. Unfortunately, the final two chapters contain a plot twist and resolution that detonate most of the book’s themes and leave it helplessly wounded.

(I consider my Burroughs’s articles to be analyses rather than standard reviews, and therefore spoilers are assumed. ERB’s work also tends to be difficult to spoil, since it rarely relies on shock revelations and twists. Nonetheless, here is your spoiler warning for what follows.)

In Chapter 16, Sing Lee enters into exposition mode to reveal that Bulan isn’t a chemical creation at all. He’s an amnesiac man whom Sing discovered unconscious in a boat near the island. Because Sing didn’t want Virginia to be forced to marry whatever beast came out of Professor Maxon’s next chemical batch, he switched the memory-less man into the vat to trick Maxon. Bulan’s true identity is Towsend J. Harper Jr., a wealthy New Yorker who spotted Virginia and her father getting on a train and decided to follow her because — well, because he fell in love at first sight and thought stalking the woman across half the world until suffering a head injury was the best way to go about pursuing his attraction. And because Burroughs needed a trouble-free romance to wrap up everything.

While we’re here: the chest everyone wanted to steal contains … biology books. This isn’t the worst way to resolve the treasure chest subplot, but then I didn’t care much about the chest to start with.

That Number Thirteen/Bulan never had a real conflict about his humanity, only the illusion he did, and that all his concerns vanish in the final chapters deadens one of the best aspects of The Monster Men. I can’t read Edgar Rice Burroughs’s mind and explain why he took this route — one he could have avoided without extensive re-writing — but I can hazard a guess. Burroughs was a bridge between the century of romances written before him and the new age of adventure he helped catalyze, and during his first books he occasionally made mistakes that pushed him to the earlier side of the divide (The Outlaw of Torn being the best example). The sunny romantic conclusion, where boy and girl are happily united thanks to a W. S. Gilbert last-minute reveal, drew Burroughs back from the edge of the uncomfortable possibilities in his Frankenstein/Dr. Moreau tale. The lure of what was still perceived of as popular with general readers won out at the end.

Except not for long. It wasn’t in this novel, but a novel Burroughs wrote soon after where he took the “man without a soul” idea and merged it perfectly with his own high-adventure and romance sensibilities. That novel is The Mucker, which removes the science fiction of The Monster Men (although keeps the outrageousness; cannibal samurais, you know) but might be thought of as the story done right. Burroughs started writing The Mucker a few months after completing The Monster Men, and the later book’s story of a bestial man who comes to recognize his humanity through his love for a woman while on a Pacific Island works in a way the adventures of Number Thirteen never manage. Number Thirteen/Bulan has an abortive development and his character growth vanishes in the smoke of the reveal. Billy Byrne in The Mucker takes the full journey. He starts as an inhuman beast and concludes as a man with a soul — and still doesn’t end up winning the heroine. (Not until the sequel, that is.) This is the story satisfaction The Monster Men should have. Burroughs learned fast from his errors during this time.

Even with the numerous mistakes, The Monster Men retains a basic excitement that keeps it more readable than later-period Burroughs. This is still ERB at his most actively imaginative and energetic. Even if the novel squelches its best premise in the close and dashes about too much with the routine treasure-hunting and abduction business, the passion is there as well as a handful of excellent characters and a half-complete attempt to grapple with the meaning of the soul. And only a few months after, we got The Mucker, so the experiment was worth it.

See you next time for Back to the Stone Age and the Second Pellucidar Era.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

I have to agree with your take on this. The ending was a bad call.

I would also have to say that ERB missed an opportunity to really get some mileage out of the other “monsters”. They are a sort of “Frankenstein’s Dirty Dozen” who might’ve added even more color and depth to the tale with a bit more attention paid to their characterization. They are truly “born to die” in a “world they did not create”. As it is, they follow Bulan with a certain amount of loyalty and do much to further the rescue of Virginia. They die, unloved and unmourned; the ultimate outsiders — but with a certain kind of hopeless bravery.

Did anyone other than myself see them as a kind of proto-orcs?

I still believe the heroic “Sing Lee” in this tale is the same as the estimable “Sing” in THE RETURN OF THE MUCKER. Considering the links you’ve pointed out, the possibility is strong. It’s not like ERB wasn’t tying in characters from other books during that period. Barney Custer and Tarzan, for instance.

Bulan’s whip was a great, albeit impractical, touch. This novel was also my first exposure to the fascinating Dyak culture. Some of it may be due to nostalgia, but I still hold a very warm place in my heart for this novel.

@Deuce – Yes, seeing Bulan’s companions slowly killed off, whittled down from fight after fight, until it comes down to Three, Twelve, and Thirteen is powerful. I particularly like Number Twelve, whom ERB at first paints as if he’s going to be a main adversary. But then he becomes Bulan’s closest ally among the others because he’s the nearest in intelligence. But he’s also just not quite human enough to have any reason to want to be part of society either. He’s pretty much doomed (as are the others) but feels more aware of it. I think ERB could’ve done much more with the relationship between Bulan and Number Twelve.

ERB can be really hit or miss, in my experience, often in the same book, sometimes in the same chapter!

And, speaking of monster men, sometimes a man’s a monster, a beast on the run, he’s a virus you can’t stop with a gun. Evil plans from a mind insane, loud screams from the house of pain. Huuh!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NVrijrV5cYs

I read this one many years ago, and I remember it as pretty clunky, but even when he was off his best game, ERB had the knack of blending conventions that were antiquated even in 1919 with his bizarrely elaborate “prose” and still coming up with products that are oddly charming. The Monster Men is in that category, I think.

I also read this one once, many years ago — if I recall correctly, I read it in pretty much one sitting. (That’s one nice thing about Burroughs — with very few exceptions, his books are conducive to just sitting down and reading them cover to cover.) I honestly don’t recall much of anything about it, and based on this review I don’t think it’ll be going back into my queue any time soon.

Just finished listening to this book. I didn’t mind the pulp elements, it was fun watching Bulan and Monster squad adventuring around Borneo, I wish more time was spent with him.

Von Horn dare I say is one of ERB’s most memorable villains? He gets a lot of screen time, a true rascal and his ending is grisly. The reveal of the chest’s contents is cheap, but Von Horn’s death made up for it.

I enjoyed the book. Can’t wait to try the Mucker, heard so much about it.

Now THAT’s a good one!