So You Want to Be a Movie Star – Really?

Joan Crawford

So you want to be a movie star? Big house, swimming pool, fancy cars, lavish parties, gala premiers, fawning flunkies, fame, fortune, the envy and adulation of millions — all the accoutrements, privileges, and perquisites of a luxurious lifestyle undreamt of by lesser mortals? It’s quite a life, I hear.

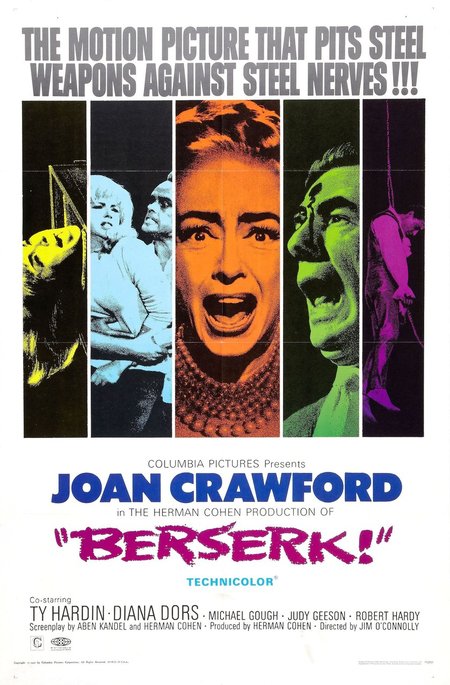

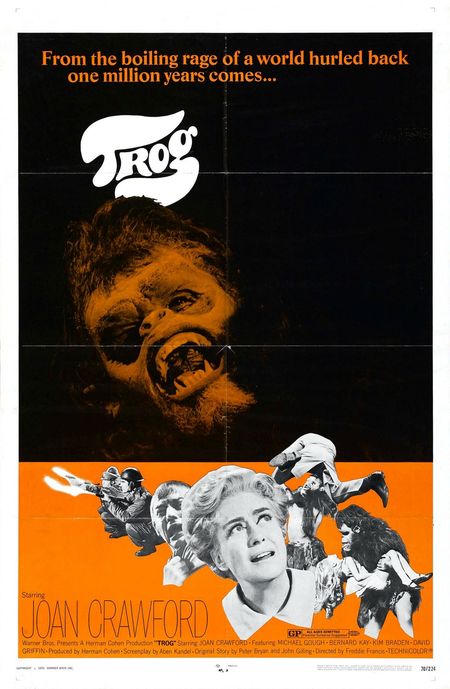

But of course, there’s always the flip side (everything has a flip side), when the years start to mount up and more and more choice parts go to fresh young things with a little more rubber on their radials, and the waiting time between films grows longer… and longer… and you, a big talent, a serious thespian, a major star, finally find yourself slinking onto the sound stage to take up your role in a low-budget exploitation movie. You can’t even salvage a little dignity by hiding somewhere in the middle of the credits, can’t pretend that you’re doing a campy cameo as a favor for an old friend. Nope — honey, you’re the headliner, the main attraction, that’s your name up there in big, bold print, right up there for everyone to see on the posters of Strait-Jacket… and Berserk!… and… please, God, no… Trog.

Yup. It’s a hell of a life, being a movie star. Just ask Joan Crawford.

Joan Crawford and Clark Gable

Joan Crawford (the one-time Lucille Fay Le Sueur of San Antonio, Texas) was the real deal, a genuine when-dinosaurs-roamed-the-earth Movie Star. There were none bigger; in her glory days during the thirties she was the reigning queen of the most prestigious studio of them all, MGM, and when Louis B. Mayer showed her the door in 1943 after her box-office had slipped a bit, she bounced back in a major way at Warner Brothers, where she won the 1945 Best Actress Oscar for her portrayal of the title character in James M. Cain’s domestic noir melodrama, Mildred Pierce.

She was also, as her adopted daughter Christina’s scarifying memoir, Mommie Dearest, makes clear, a bipolar (manic-depressive they called it in those days), obsessive-compulsive alcoholic, a hellish blend that meant that the one thing she should never, ever have attempted was parenthood. However, one of the occupational hazards of superstardom is thinking that you can do anything.

During her prime, Crawford worked with the cream of Hollywood. She was guided by elite directors like Howard Hawks, George Cukor, Michael Curtiz, and Otto Preminger, and she appeared opposite the biggest stars in the business, names like Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable (eight times), Gary Cooper, Norma Shearer, Bette Davis, and Fred Astaire (among her other talents, Joan was an accomplished hoofer). She even shared a film (1933’s Dancing Lady) with Ted Healy and his Stooges, Moe, Larry, and Curly.

Before William Castle

It’s not known if she took that last one as an ill omen, but she probably should have, because thirty years later, by the early sixties, Crawford (now in her early sixties) was faced with a world in which the Stooges were potentially bigger stars than she was. The A-list directors, the top costars, the scripts by the best writers, decent offers of any kind, in fact, were all gone. She finished her almost half-century in film with a handful of embarrassing stinkers because, of course, great stars have bills to pay just like everyone else.

By 1964, nothing was left for Crawford but to accept a proposition from ultra-cheap schlockmiester William Castle, a man who made Roger Corman look like a spendthrift. Castle is best remembered as a shameless self-promoter and gimmick master; he’s the man who brought you “Emergo!” for House on Haunted Hill (a plastic skeleton dangled over the audience during the film’s climax, such as it is), “Percepto!” for The Tingler (small motors attached to the underside of theater seats to produce a vibrating effect when the monster gets loose), and “Illusion-O!” for 13 Ghosts (plain old cardboard 3-D glasses), to say nothing of “Oh, My Aching Back, Oh!” for the rest of his uniformly awful movies. He had a part for Joan — the lead part, no less — in a little thriller called Strait-Jacket. (Crawford actually took her first step on this death march a couple of years earlier, with 1962’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? But that movie, a bubbling cocktail of hysterical gothic horror, was in its own overripe way a serious movie by a man — Robert Aldrich — who was at least intermittently a major director.)

After William Castle

Tired of wiring motors under theater seats, Castle hit on a very simple and effective gimmick for Strait-Jacket: Joan Crawford. Certainly having someone other than “Who?” as the star of his movie was a decided change of pace, though Castle being Castle he couldn’t resist striking his usual grace note on the movie’s poster, which trumpets, “WARNING! STRAIT-JACKET VIVIDLY DEPICTS AX MURDERS!” (Note the characteristic low budget touch — Mr. C apparently couldn’t afford the “e” in “axe.”) It could have been worse, I suppose; it could have read, “HEY KIDS — AX MURDERS!” With William Castle, you’re grateful for small mercies.

Strait-Jacket is a particularly tawdry example of a flourishing sixties sub-genre: the Psycho rip-off. (Hammer Studios alone made about twenty of them.) It actually has a better pedigree than any other such movie — it was written by the author of Psycho, Robert Bloch. There’s no more hallowed Hollywood tradition than ripping yourself off.

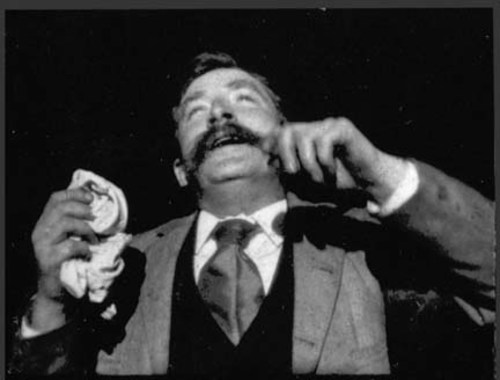

Fred Ott’s Sneeze

The plot of Strait-Jacket is so grindingly obvious that the first audience in movie history — the late-Victorian bunch who soiled their bloomers over Fred Ott’s Sneeze — would have had it figured out in about two minutes. Its crudities certainly incline you to believe that Psycho owes far more to the excellences of Alfred Hitchcock’s direction, Joseph Stefano’s script, and Anthony Perkins’ and Janet Leigh’s performances than it does to Robert Bloch’s source novel.

Strait-Jacket opens with a newspaper front page bearing a full-page photo of a snarling Joan Crawford, and a voice bellows the headline: “Extra! Extra! Read All About It! Love Slayer Insane!” If that doesn’t boost circulation, nothing will.

A voice solemnly intones, “Lucy Harbin was declared legally insane today,” and then takes us through a quick montage of the case — on a “hot, sticky Saturday night,” while Lucy is out of town, her husband Frank (who is seven years younger than his wife and is also — holy crap — Lee Majors!) meets up with a “former girlfriend” at a local honkey-tonk and takes her home to discuss the merits of the Boston Celtics’ full court press… or something. Frank doesn’t remember — or doesn’t care — that his young daughter Carol is sleeping in the next room… except the child isn’t really asleep.

Frank is also unaware that Lucy has decided to come home early, and as we see her step off the train, the narrating voice (who is the now-adult Carol, we will soon learn) tells us that Lucy is “very much a woman, and very much aware of the fact.” (I’m just guessing here, not being a woman myself, but I would think that that’s one of those things you would pretty much have to be aware of.) The poster can shriek all it wants about bloody dismemberments, but the grisliest thing in the movie is this soft-focus shot of a fifty nine-year-old Crawford stepping onto the platform as the cinematographer and make-up artist use all the dark arts at their disposal to try to make her look like a woman in her early thirties. (“A little less light… ok, a lot less light… let’s try a little more steam… ok, a lot more steam… Mr. Castle, sir, it’s not working, it’s just not working… ) The problem could easily have been solved by a quick visit from one of those animated popcorn boxes, singing, “Let’s all go to the lobby, let’s all go to the lobby… ” but nobody thought of it.

As Lucy strolls up to her house, she looks through a window and sees Frank and his girlfriend side by side in bed, sawing logs after their exhausting evening. She instantly yanks an ax out of a tree stump (we’re never told exactly where this story takes place, but it ain’t Manhattan) and slides into the bedroom. After pausing for a moment to ensure that the grownups have time to send the kiddies scampering to the snack bar for some raisinets and goobers, she hefts the ax and goes to work. Don’t get too excited though, because all the Good Stuff is shown only as shadows on the wall — there’s not even any blood (this is a William Castle picture, remember — “We can’t afford Joan Crawford and fake blood!”), though you do see the shadow of Lee Majors’ severed head bounce off the mattress. Whoopee. So much for the promises of posters. Joan can’t be faulted for this, as she does her part by swinging away for all she’s worth. I have no doubt she was picturing Louis B. Mayer with every chop.

Strait-Jacket – Ax Me Another

Need I say that young Carol has crept from her bed just in time to witness this disappointingly un-horrifying moment of awful horribleness? Who knows what dreadful effect such a not-at-all gory moment of extremely mild gruesomeness and brutally tragic letdown will have on her tender psyche? You know darn well what kind of effect it will have, but Robert Bloch and William Castle are hoping that for 93 minutes you’ll pretend that you don’t, and even if you’re not willing to play dumb, what the hell. You already paid for your ticket, so you’re really not as smart as you think you are, are you, wise guy?

The prologue ends with Lucy raving in a strait-jacket (product tie in!) and the story proper gets underway in the next scene with the now cured ex-maniac tasting freedom after twenty years in the nuthouse. (Save your tweets of outrage, please. I am a person of rare sensitivity and discretion, but people in movies like this don’t go to mental health facilities — they go to nuthouses!)

Having missed the white-knuckle excitement of the Eisenhower administration, after her release a chastened Lucy comes home to live with her brother Bill and his wife on their farm, where she hopes to restart her life and reconnect with her daughter. Carol (Diane Baker) lives there too, marking time until her marriage to her affluent boyfriend Michael and seething with shame over her connection to her mother (or the murderess, as she insists on calling her). Poor Carol just can’t shake the feelings of inferiority that come with being a girl from the wrong side of the ax… er, tracks.

Strait-Jacket – A Little Off the Top

The rest of the movie mostly consists of Lucy getting the vapors every time she sees anything sharp — a hatchet (of course), a carving knife, a sculpting tool (Carol sculpts and is especially adept at doing heads; you never know when something like that will come in handy). The young lady seems oddly anxious to expose her still-psychologically fragile mother to things like carving a juicy roast and chopping the heads off chickens. She also encourages Lucy to dye her hair and dress like a much younger woman, all of which bring about a startling alteration in Lucy’s personality — she changes from a timid and uncertain woman to a loud, brash floozy; she even makes a pass at Carol’s fiance. I hope the luckless actor, John Hays (who was all of twenty eight at the time), got a couple of days off to regain his composure after completing that scene; I know that I always have to rush to the bathroom at that point whenever I watch the movie.

After Lucy regains her edge (oh shut up, you knew it was coming) folks start disappearing or turning up dead; she also starts having “hallucinations” (heads appear in her bed and then vanish by the time she fetches someone to come look — how about that?) and this leads people to think that perhaps twenty years in the asylum was not quite enough. The situation comes to a head (sit down, that’s a perfectly acceptable phrase) when Carol takes her mother, now the epitome of a swinging single (ha — got you with that one), to meet her fiance’s rich and snooty parents. The evening does not go well, and after everyone leaves, the festivities culminate with the violent dispatch of Michael’s father. The killer is apprehended almost in mid-chop, and turns out to be… Carol, dressed in one of her mother’s provocative dresses and wearing a Joan Crawford mask, of all things. It’s simply impossible to be surprised, and you’re so relieved that the movie is almost over you don’t even wonder how the crazy kid smuggled an ax into her boyfriend’s parents’ bedroom closet. (Yikes! That’s an awkward way to end a sentence. What the hell – it’s an awkward way to end a movie.)

The last scene shows Lucy ready to go back to the madhouse, this time to help her daughter through her own ordeal. At the very least, she’ll be able to give Carol tips on bribing the Screws with cigarettes. So the girl’s twisted plan to purge her shame and clear the way for her Cinderella marriage by getting her mother to go back to the asylum worked… sort of. It’s truly a happy ending, in that this is one of those movies where everyone is happiest when it ends, though those who understandably bolted from the theater before the credits rolled missed the movie’s wittiest touch — in fact, its only witty touch: the Columbia Pictures lady with her chopped off head at her feet. It’s surprising Castle got away with that… or maybe it isn’t. How likely is it that anyone from the studio actually sat all the way through this thing?

Strait-Jacket – Headless Columbia

Strait-Jacket is a dreadful movie. Its cheapness goes beyond the kind that merely comes from a low budget; its poverty is of the soul. Not surprisingly, the best thing in it is Joan Crawford. In her early scenes, as a subdued, shy woman tentatively trying to regather the threads of a lost life, she’s actually quite touching. The later scenes, with her brassy, grotesque imitation of a wild, younger self, are undeniably risible, but the risibility isn’t Crawford’s fault. It just what the sleazy script and her ham-handed director asked from her and, professional that she was, she gave it to them.

Joan Crawford did not win the 1965 Best Actress Oscar for her portrayal of Lucy Harbin in Strait-Jacket. There’s no justice in the world.

In the year after Strait-Jacket, Crawford did two more low-budget, no-prestige movies, Della and I Saw What You Did, the latter also directed by William Castle. Both are psychological suspense stories rife with dark secrets and psychotic killers, unenlivened by bland direction and excruciatingly dull scripts. However, they at least attempt to maintain a pretense of being real movies, and that kept Crawford’s career from quite entering the phase of complete organ shutdown. That had to wait for her penultimate film, 1967’s Berserk!

In Berserk! (love that exclamation point) Crawford plays hard-charging, tough as nails Monica Rivers, the owner and ringmaster of a traveling circus, replete with clowns, high-wire artists, elephants, lions, magic acts, jugglers… and murder! Less than ninety seconds into the movie, a high wire snaps and, as the tightrope walker plummets to the ground, it somehow wraps itself around the man’s neck and strangles him before an appalled (yet oddly appreciative) audience. No refunds, folks. Getcher popcorn here! (And get those clowns off their butts and into the ring, quick!)

Police investigators speedily determine that the wire has been tampered with, and the violent death of the Great Gaspar (that name couldn’t have been intended as a pun, could it?) is soon followed by another… and another. Yes, someone is killing off the performers of the Great Rivers Circus, and it can’t be because they’re just awful or they all would have been pushing up daisies long ago. Some sinister hidden motive must be at work — but whose?

Gaspar isn’t cold yet before arrogant aerialist Frank Hawkins (Ty Hardin) shows up to lobby for his job. So maybe Hawkins is the killer, removing a rival on his march to fame and riches on the second-rate circus circuit. But then circus co-owner Albert Dorando (Michael Gough, familiar from whining his way through many a Hammer horror movie) gets a tent peg driven through his forehead. He was on the outs with Monica (who is also heard to muse that gruesome deaths are good for box office), so maybe she’s the mad killer! But wait — ultra slutty Matilda (Diana Dors) gets sawn in half (literally sawn in half) during a magic act gone wrong… but everybody hates her, so that doesn’t help much. Finally, Hawkins receives an expertly thrown knife in the back while sitting on a chair that he has balanced on a high wire fifty feet above the arena floor. (That’s why so few take up tightrope walking — it makes you extremely vulnerable to knife-throwing homicidal maniacs.) Hawkins understandably tumbles off and is impaled on a bed of knives that he had placed under the wire to heighten the danger of the act. Congratulations, Frank — you’re cleared!

Berserk! – Joan as Abe Vigoda

There’s no mystery this time, though. The knife thrower is immediately revealed to be Monica’s daughter Angela, who got kicked out of an exclusive girl’s school and joined the circus against her mother’s better judgment… two thirds of the way through the movie! Before that, (while most of the victims were being killed) we didn’t even know of Angela’s existence. This qualifies as a blatant cheat, which is only slightly alleviated by the fact Berserk! at least allows us to see a little blood now and then.

Angela was jealous of the circus, you see — it took too much of Monica’s attention. Lack of mother love turned the teen into a crazed killer, as it has so many others. Unlike Strait-Jacket however, here there is no possibility of tender reconciliation (even if in a prison yard or padded cell), no chance of making up for past parenting mistakes, because Angela is conveniently fried by a bolt of lightening as she flees the circus tent. Another happy ending!

Berserk! was the movie that made it clear to the sixty three year old Joan and to everyone else that the evenings spent sleeping in a cryonic chamber and the mornings spent bathing in virgins’ blood were no longer doing the trick. Indeed, in some of the film’s scenes Crawford looks remarkably like Abe Vigoda during his Barney Miller years, which, while not a crime or moral failing (time catches up with everyone) did make her status as an even vaguely credible romantic lead highly problematic, to say the least. (It has to be admitted, though — Joan’s ringmaster getup reveals that even at that late date, she still had a nice set of gams. If only her leading men could have made love to her knees… )

This must have been apparent to no one more than the thirty seven year old Ty Hardin, who stopped reading the script before he got to the intimate candlelight dinner in Monica’s trailer scene, the one where Joan is decked out in a negligee. Putting vaseline on the lens is an old cameraman’s trick that goes all the way back to the silent days, but Ty Hardin may have been the only man in cinema history to have to vaseline his eyballs.

Hardin fled into the night as soon as his last scene was shot. Rumor has it that he has spent the remaining years of his life as a carnival geek, trying to sear the taste of Joan Crawford from his mouth with chicken heads and cheap bourbon.

Difficult as it may be to believe, Berserk! is in most ways even worse than Strait-Jacket. While Berserk! is in color and Strait-Jacket is in black and white, this is no advantage. Black and white would actually have been better, as color does nothing but accentuate the cheap, seedy look of the movie. Even a better look wouldn’t have helped much though, because where Castle’s film does have a few moments of over the top, nutty energy, from start to finish Berserk! just feels depressed and listless. It also has the great failing of all films that take place under the Big Top — far too much time is taken up with dull footage of an actual circus, in this case the Billy Smart Circus, which seems from the testimony of Berserk! to have been a rather flea-bitten, rundown affair. I actually like circuses, but they are preeminently a live medium; their color, speed, and excitement just don’t translate well to the screen. If Cecil B. DeMille himself couldn’t manage to do it in his sawdust epic The Greatest Show on Earth, then Jim O’Connolly, the hapless director of Berserk! had little chance of doing it in his much more modest film.

Berserk! – I Should Have Read the Script

Worst of all, unlike the earlier movie, Berserk! gives Crawford no opportunity to do anything that resembles real acting — with one exception. In a scene where theatrical agents are trying to persuade Monica to take on their performers (to, you know, replace all the people who are being murdered), Crawford speaks the following line: “Look, don’t waste my time with these broken-down has-beens; some of them are as old as my elephants and twice as wrinkled!” Okay, maybe it’s not exactly great acting, but for having enough steely self control to say that line with a straight face (and without a trace of irony) Joan Crawford should have gotten some kind of honorary Oscar; call it the Ben Kingsley Award. Aside from counting the house while the Billy Smart Circus wows the rubes, she has little to do except rush from one bloody corpse to the next, all the while barking out “the show must go on” cliches to the tune of calliope music. It’s not exactly a formula for success.

After Berserk! the trajectory of Joan Crawford’s career was as clear as the fate of the Confederacy after Gettysburg; there was no place to go but down. By 1969 there was nothing left for her but her own cinematic Appomattox… nothing left but Trog.

The tragedy (in more ways than one) begins when three footloose spelunkers, Malcolm, Bill, and Cliff (I’m not going to tell you the actors’ names — surely the statute of limitations for being an accessory to a crappy movie has expired by now) discover an unknown cave. After stumbling around for a bit exclaiming about their fabulous find — though no one remarks about how bright it is in here, almost as if it were being lit for a movie — Bill gets briefly separated from the others. Just that quickly, he is assaulted and beaten to death by something his companions get only a fleeting glimpse of, but that we see all too well.

The assailant looks for all the world like some guy clad in animal skins and wearing an ape mask. The vile murder done, he flees back into the recesses of the cave while Malcolm and Cliff run for their lives. Cliff is so psychologically shaken by his brush with a dude in silly makeup that he’s sent for recovery to the “Brockton Research Centre,” a place run by the famous Dr. Brockton herself (Joan Crawford, naturally). Why he winds up in her care is something of a mystery, as she seems to be some sort of expert on early man (we are told that she is the author of Social Structures in Primates) and her research center is neither hospital nor nuthouse, but is instead an institution devoted to anthropological studies. They don’t even seem to have any bedpans.

It’s a moot point, because Cliff exits the movie forever at the fifteen minute mark (only Bill was luckier), but before he does, he has time to give Dr. Brockton a jumbled account of what he saw. “Horrible… horrible… that face… those eyes,” he mutters in his delirium. He’s looking directly at Joan when he says it, so we have to take it on faith that’s he’s talking about what he saw in the cave. (What a cheap shot! And really, it’s not warranted; Crawford looks fine in Trog. This time she’s much younger than her leading man — like 1,000,000 years younger — and so in that respect at least she comes off much better than she did in Strait-Jacket or Berserk!) When Dr. Brockton asks him for a better description, Cliff can only whisper “Monstrous… like nothing I’ve ever seen before!” What do you want to bet that when Cliff was saying those lines, Joan was picturing Bette Davis?

With this detailed information in hand, Dr. Brockton convinces Malcolm to take her into the cave. Once in there, they snap a picture of the killer creature, which they then use to convince the cops to go in themselves and capture the beastie.

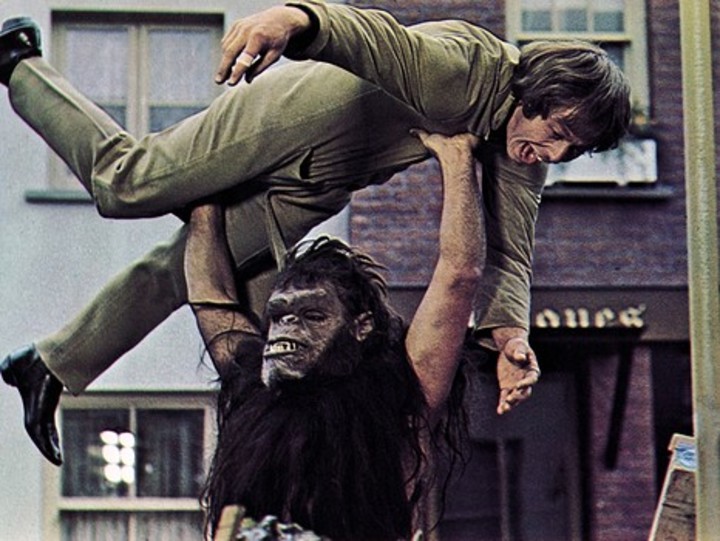

Trog

Once the cave dweller is lured to the surface and properly subdued (Joan fires a couple of tranquilizing darts into him, a skill she learned dealing with all the big egos at MGM; it once took her three darts to bring down Katherine Hepburn), Dr. Brockton takes charge of him. She instantly dubs him “Trog” and asserts that he’s a holdover from “another age… say, ten million years ago when some of our ancestors like the gorilla, the ape, and the baboon were beginning to leave the forests and the jungle, learning how to walk upright, and crystallized into some kind of resemblance to the Neanderthal man.” (It’s that “crystallized” that lifts this into bad dialogue heaven.) The doctor furnishes Trog with a nice, comfortable cage at her institute, where she can feed him rubber lizards and study him at her leisure. He seems to be ok with all this; not having had a date since the Mesozoic era, Trog knows he can’t afford to be choosy.

The remainder of the plot is barely worth recounting, except as an occasion for science so loopy and dialogue so ridiculous that they verge on the surreal. You’ve seen enough movies of this kind to know how it goes: Dr. Brockton loves and fights for Trog while others (mobilized by the greedy and intolerant civic meddler Sam Murdock, played by Michael Gough — back for more after Berserk! God bless him) seek to have the creature destroyed, asserting that he’s a dangerous, murderous monster.

It’s hard to know what they’re so afraid of. There’s nothing exceptional about Trog aside from his apish features and the hairy mantle around his shoulders — it’s never clear whether this is an animal skin like his loincloth or is supposed to be his own hair. Either way, it does a poor job concealing the fact that, far from being an imposing physical specimen, Trog is in reality a short, bandy legged, rather pudgy guy. His gym membership expired 150,000 years ago and he never got around to renewing it. You know how it goes — you get busy banging rocks together and gnawing on raw lizards and, what with one thing and another, a glacial epoch passes before you know it. (After that paragraph, you may think that I owe Joe Cornelius, who played Trog, an apology. On the contrary. I think he owes me an apology.)

Trog and Joan

A tug-of war is fought in the courts, with Dr. Brockton opposing Sam Murdock and making impassioned speeches before a magistrate who can neither make up his mind nor control his courtroom. (I would have thrown Murdock out the first time he interrupted with an outburst, not the twelfth.)

All the while, back at the institute Dr. Brockton is continuing to torture, er, study Trog to see what makes him tick (she calls it “an opportunity to lift the veil from the past.” No — really!) She plays music for him (muzak soothes him while the kind of “rock and roll” dope smokers on Dragnet used to play gets him all riled up), gauges his emotional reaction to colors (green good, red bad), gives him dolls to play with (Dr. Brockton also authored Gender Plasticity in Troglodytes), and teaches him to play ball, until a nosy dog shows up to spoil the fun; Trog demonstrates his progress in socialization by breaking the critter’s spine.

Dr. Brockton becomes convinced that Trog is completely harmless (no surprise there — she must be a cat lover) and also that he’s the missing link, the “connection between the creatures of early civilization and man as we know him today.” When a reporter asks her the big question, namely how did Trog survive into the modern age, Joan spews a speech that would make every purveyor of snake oil and psuedoscience from Victor Frankenstein to Dr. Oz to the White House press secretary of your choice glow with pride: “Conceivably, Trog was frozen solid during the long, long glacial age — a state similar to cryogenic suspension. Then as the underground streams and currents brought more and more warmth to the frozen atmosphere, his body thawed out. We now know that human sperm, red blood cells, bone marrow cells, even skin, can be brought back to life after freezing.” She wishes. Well, earlier she did say that “people on the outside think all scientists are a little deranged.”

Brockton eventually convenes an international group of scientists; they do a little experimental brain surgery on Trog to try and get him to speak. This is the occasion for a peek into Trog’s mind, which consists entirely of stop-motion dinosaur scenes from Irwin Allen’s 1955 flop, Animal World. After the operation and stock footage viewing, Trog is indeed able to speak the name of the doctor’s daughter and research assistant, Ellen. What the… how… that’s completely… oh, forget it.

Finally, just as it seems that Trog will learn enough English to start either his memoirs or a lawsuit, Sam Murdock breaks into the institute and frees the creature, hoping that that Trog will seal his fate by going on a rampage. Trog promptly complies, but starts by killing Murdock. He then ambles into town, where he piles up a lot of property damage and two or three corpses. It’s all a misunderstanding, of course, but the police have had enough and, despite Dr. Brockton’s protestations, chase Trog back to his cave, where they proceed to riddle the missing link with enough machine gun bullets to make him pitch forward and impale himself on either a stalagmite or a stalactite — I can never get that straight. (Trog also kidnaps a little girl along the way, but I really, really don’t want to go into that, if it’s okay with you.)

A heartbroken, defeated Dr. Brockton walks slowly away from the camera. Science, love, understanding, tolerance, mankind’s insatiable quest for knowledge itself have all suffered a terrible setback. Really, coming to the end of this movie, it’s hard not to feel that damn near everything has suffered a terrible setback.

Bad movies in all their flavors — dull, dumb, sloppy, uninspired, run of the mill — are a dime a dozen, but movies that are memorably bad, that are bad enough to hold to your heart forever… well, those come along very rarely. Trog is one of these dark gems. Joan Crawford brings a crazed conviction to an utterly unworthy role, and when you add the absurd monster, stupid science, and beyond-goofy dialogue, you have a classic of its kind. It’s just not the kind that a great star would want to end with.

But such it was; when Joan Crawford walked away from the camera at the end of Trog, it was the last scene shot on the last day of filming of the last movie she would ever make. She wasn’t just walking away from a day’s work on a silly, junky piece of schlock; she was walking away from a movie career that began in 1925 and that had lifted her up to heights that few others ever reached… and then had let her a long way down. She knew it was the end; she couldn’t go any lower unless she started doing the sorts of “movies” that used to be shot on 8mm film and were mailed in plain brown wrappers. The progress from tearjerkers to jeerjerkers was complete; one look at Trog and she knew that it was time to go.

Joan Crawford certainly wasn’t alone in her predicament. Economics and age being what they are, a lot of people wind up doing films that are far beneath them, and there are many ways that big stars deal with being in terrible movies. There’s Hangdog Humiliation (Richard Burton in The Sandpiper), Eccentric What-the-Hellism (Christopher Plummer in Star Crash), Aloof, Pained Professionalism (Laurence Olivier in The Betsy), Willed Invisibility (Christopher Lee in She), and perhaps most commonly, Give-Me-My-Check-and-Let-Me-Get-the-Bleep-Out-of-Here (Orson Welles in… oh, you name it).

Doing Strait-Jacket, Berserk!, and Trog was, quite honestly, a sad, embarrassing end to a great career — but here’s the thing. It wasn’t as sad and as embarrassing as it could have been, because Joan Crawford didn’t choose any of those easy outs. When you finish watching these gawdawful movies, you have no doubt that this woman was a great star, and you know what it was that made her great. She had worked with the best talent in Hollywood, at the biggest studios, on top-dollar, prestige productions. She had an Oscar on her mantelpiece. So she had no illusions; she knew full well how wretched these movies were, probably more so than anyone else working on them… and she still gave them everything she had. She gave William Castle and Jim O’Connolly just as much as she had given George Cukor and Michael Curtiz. Ty Hardin and Joe Cornelius didn’t receive an iota less than she had given Gary Cooper and Clark Gable. She worked every bit as hard for reeking-of-poverty Herman Cohen Productions as she ever did for MGM or Warner Brothers.

She certainly had no doubt that these were three very bad movies, but she treated each of these utter stinkers as though it were the best film she’d ever made. When the cameras rolled, she knew her lines, hit her marks, and held nothing back.

All in all… I think that’s a pretty good way to go out.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Reading for the End of the World.

U used to have a huge crush on Faye Dunaway (Bonnie and Clyde and Chinatown) but it soured after Mommie Dearest. As to William Castle the major memory I have of him was Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine devoted a large piortion of an issue to singing his phrases (an issue in the low 30s I believe) and when you’re a kid you take these articles seriously without question. Until I grew up and realized Famous Monsters and to my mind infamously Starlog are in the business of praising filmm and books and passing by on the criticism so your perspective is much appreciated and at my advanced years said with respect-amusing.

I have a sneaking affection for Mommie Dearest (the movie) – it’s so crude and lacking in nuance that I’m able to watch it as a perverse, over-the-top comedy.

The recent FX mini-series (or anthology series, if you prefer) Feud: Bette and Joan offers a very sensitive pair of portraits of the artist as an older woman. Jessica Lange as Joan and Susan Sarandon as Bette wring out a lot of the pathos and pain and paranoia of being an aging star on the outs with the Hollywood movie machine. And, yes, it offers a lot of glimpses of Ms. Crawford’s last films. With John Waters as his idol, William Castle, no less.

I’m fonder of William Castle than the above might indicate. The 1993 Joe Dante film Matinee features John Goodman as a Castle-like producer/director, and is a real delight.

I look forward to your review of Mant!.