Books and Craft: World Building and the Importance of Setting

|

|

After a longer hiatus than I had a intended, I am back with the second in my Books and Craft series of articles on the elements of story telling that make “classic” and “must-read novels”… well, classic and must-read. In my first entry, I wrote about Nicola Griffith’s science fiction masterpiece, Slow River, and Griffith’s innovative use of point of view.

Today, I turn to one of my favorite fantasy novels: Guy Gavriel Kay’s Tigana, a stand-alone epic fantasy (that rarest of all things), which first appeared in print in 1990. I actually referred to this book in my first column, while making a point that bears repeating. As with Slow River, there is no one craft element of Tigana that makes it a successful novel. Kay displays here the command of language and pacing, character development and narrative arc his readers have come to expect. Another observer might focus on one of these, or some other facet of his work, to explain why they love this novel — or any of the others he has penned in a spectacular career that now spans more than three decades.

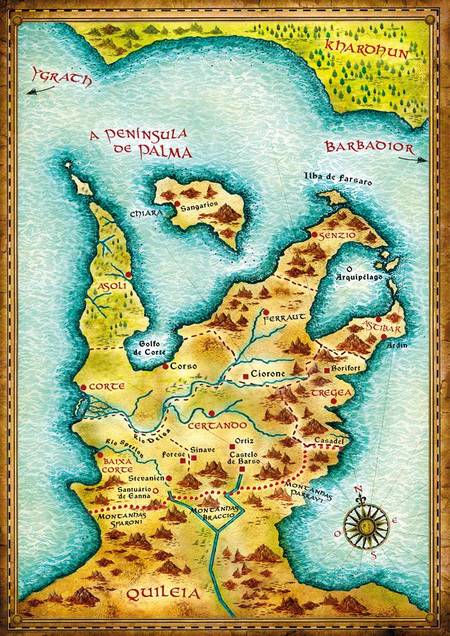

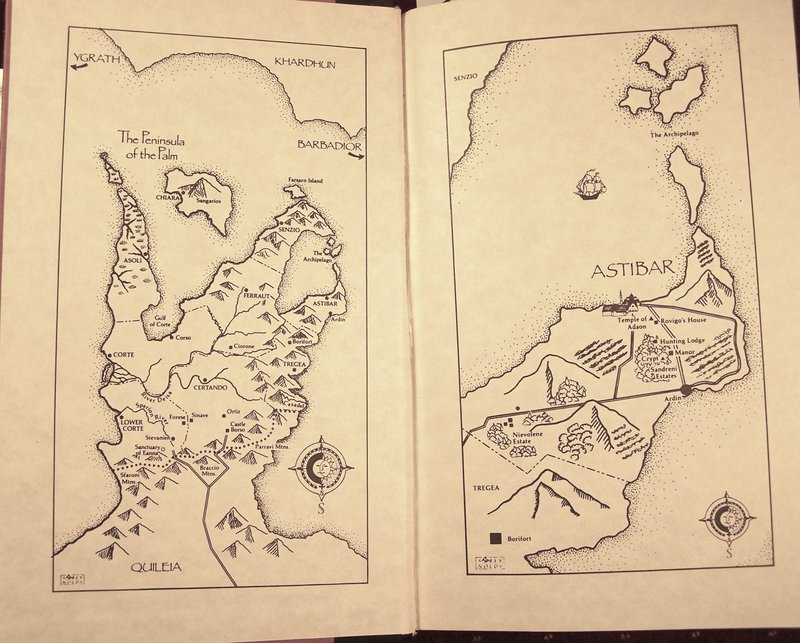

But to my mind, the defining characteristic of Tigana, the one that established it as my favorite fantasy when I first read it so many years ago, is its magnificent world building. In creating the Palm, a hand-shaped landmass of rival kingdoms that is somewhat reminiscent of medieval Mediterranean Europe, Kay has blended religion and ritual, history and politics, cuisine and viticulture and music and art, into something so rich, so alive, so compelling, that the reader cannot help but be transported with each cracking of the book’s spine. All that unfolds in Tigana’s pages flows from this sense of place.

[Click the images to embiggen.]

|

|

The story line is deceptively simple. Tigana, a province in the southern Palm, has been conquered by Brandin, the sorcerer-king of Ygrath. But this conquest comes at too high a price: Brandin’s son, Stevan, dies in an early battle. Heartbroken and bent on vengeance, Brandin leads the army of Ygrath to an annihilating battlefield victory. This, though, is not enough to slake his grief or his bitter rage. He orders every scrap of the land’s culture destroyed. Yet even this is insufficient, and so he conjures a punishment far more complete. No man, woman, or child not born in Tigana will ever hear its name again. Those native to the land might speak of their homeland, but no one from anywhere else in the world will be able to hear the word. For as long as Brandin lives, Tigana will be suffer this fate. And because he can grant himself an unnaturally long life, by the time he is dead Tigana will be lost to memory, erased from consciousness.

Only then would the full measure of the vengeance he had decreed be poured out on the bloodied ground. For no one would be left alive in the world who had any true memory of Tigana before the fall, of Avalle of the Towers, the songs and the stories and the legends, all the long bright history.

It would truly be gone then. Wiped out. Seventy or eighty years wreaking as comprehensive an obliteration as millennia had on the ancient civilizations no one could now recall.

But a resistance grows among those who have survived the war, many of whom were but children at the time, and a small band of them, led by the son of Tigana’s defeated crown prince, hatch a scheme to destroy Brandin, and a rival sorcerer, Alberico of Barbadior, who also has designs on ruling the Palm. The tale that follows is filled with intrigue, action, sex, magic, and some of the most beautiful prose I’ve encountered in any novel.

Even this overgeneralized summary of the plot hints at the complexity of Kay’s world. The politics are intricate, the rituals vivid and fascinating, the quirks and personalities of each kingdom — each city, even — defining and distinctive. I’m a history geek — to the point of having a Ph.D. — and part of what draws me to Kay’s world is the sense, which I’ve had as well in real-world places like Wales, Andalusia, and Provence, of history imbuing the air, the water, the food and wine, the discourse of each day. Because with that awareness of history comes as well an awareness of the power of memory. And this novel is entirely about memory — its poignancy, its fragility, its fundamental importance.

As I write this, I search the novel for passages that might describe for you one detail or another of this magical world, so that you might appreciate it as I have come to over the years. (This is one of those books to which I return again and again. I’ve read it more times that I can count, more times than my first copy could endure, and I’ve assigned it to many a writing student.) But that would be a bit like taking a picture of a slope of Denali and hoping the image can convey the mountain’s scale.

Instead, I offer this passage, in which our protagonist, Devin, a young musician who learns that he is originally from Tigana, hears the name of the province for the first time.

“Thank you,” Devin said. He didn’t seem to be trembling anymore. Around a difficult thickness in his throat he went on, for it was his turn now, his test:

“Tigana. Tigana. I was born in the province of Tigana. My name… my true name is Devin di Tigana bar Garin.”

Even as he spoke, something akin to glory blazed in Baerd’s face. The fair-haired man squeezed his eyes tightly shut, as if to hold that glory in, to keep it from escaping into the dispersing dark, to clutch it fiercely to his need.

Part of the emotional power of this scene lies in Devin’s discovery of his family history. But equally compelling is Baerd’s fear that once more he will speak of his home and receive in return only a blank stare or a look of puzzlement at a name not heard. His relief is bittersweet evidence of the brutality of Brandin’s curse.

|

|

And therein lies the larger point. The measure of effective world building, after all, cannot be found simply in lovely prose or in complexity of backstory. Rather, we gauge the effectiveness of a created setting by how much our readers care about the survival, or, in this case, the redemption of that place. Devin’s epiphany is a turning point in the novel, the moment in which his personal tale and that of the world around him converge and become one. It is powerful and evocative, and it becomes more so with each reading.

This isn’t to say that detail and richness and description are somehow deficient to the task of creating compelling worlds. Just the opposite. The thing to remember, though, is that establishing setting is crucial not just as an end in and of itself, but as a way of imparting import to plot, of enabling readers to relate to the desires and fears of characters, of giving context and significance to battles, assassinations, mysteries, and all the other fun stuff we put in our novels.

In Tigana, we see a master world builder at work. Yes, we love the characters. But we hang on their every word and deed because we have been taken to a world of wonders, and we want to know it survives, even after we’ve read the last page.

Food for thought, and another book for the TBR list. Until next time!

David B. Coe/D.B. Jackson (DavidBCoe.com) is the award-winning author of nineteen fantasy novels and a number of short stories.

David B. Coe/D.B. Jackson (DavidBCoe.com) is the award-winning author of nineteen fantasy novels and a number of short stories.

As David B. Coe, he is the author of the Crawford Award-winning LonTobyn Chronicle, which he has just reissued, as well as the critically acclaimed Winds of the Forelands quintet and Blood of the Southlands trilogy. Most recently he has completed The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, a contemporary urban fantasy from Baen Books.

Under the name D.B. Jackson (dbjackson-author.com), he writes the Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy series from Tor Books. David’s work has been translated into a dozen languages.

David’s last article for Black Gate was Books and Craft: The Power of Point of View.

I had the good fortune to read Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie’s Jasmin’s Witch not long before I started to read Tigana, so when the “night battles” of fennel-wielding partisans began, I nearly fell off my seat. “Benandanti!”, I exclaimed. Mr. Kay’s incorporation of a delightfully obscure Italian fertility cult was a brilliant transplant of history into fantasy, a telling piece of world-building and making the setting feel “lived in”.

Thanks for the comment, Eugene. I haven’t read that, but I’ll add it to my list. Kay truly is a master of this sort of thing.

Just a follow-on: Le Roy Ladurie brings up the Benandanti via Carlo Ginzburg’s The Night Battles, which is a study of the “fennel versus sorghum” antagonists. So if your interest is following on Mr. Kay’s sources, you may wish to head directly to the secondary source. Not that Le Roy Ladurie is not worth reading for his own sake! Or Mr. Ginzburg’s other notable history, The Cheese and the Worms, a study of popular culture during the 16th century Counter-Reformation.