Modular: The New Mongoose Traveller #1 — First Impressions

Traveller is 40 years old and there’s a new edition!

Jake squeezes between some crates.

Silence.

He exhales. It seems he’s evaded the Imperial black ops team. Now if he could just find his mates in the darkened warehouse. He pushes a little further between the crates. There in the space between the aisles is the alien weapon that started this whole mess.

Jake looks left and right then ghosts into the open. Breathing hard now, he reaches out and picks up the alien artefact. Despite its bulk, it’s surprisingly light and he hefts it higher than he intended.

Lights flash along its stock. It emits a, “Whirrrrrrrrr PING!”

Shadowy figures pop up around the dimly-lit warehouse. The air fills with bullets.

One slams into Jake, punches through his chest armour. Almost spent, it still smashes his rib cage.

Everything goes dark…

Yes, this is the new Mongoose Traveller, the latest incarnation of a roleplaying game so influential that the book and TV inspirations listed in its introduction all arguably owe something to early versions of the game.

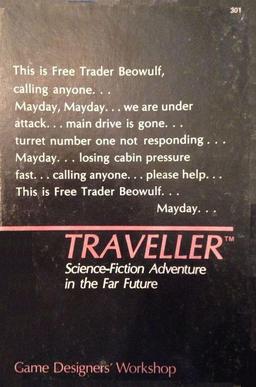

For those who’ve just tuned in, Traveller is a space adventure roleplaying game… perhaps the space adventure roleplaying game. The vibe is, “Han Solo: The Early Years“, or “Rogue 1: What they were all doing before they joined the Rebellion” or “The Expanse or Firefly, but with an interstellar civilization and less arc.”

Or, perhaps, “Elite Dangerous… but you can get off the ship and have adventures.”

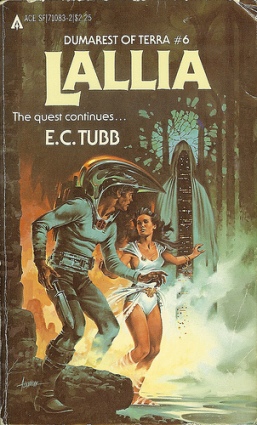

Designed to emulate mid-20th century hardboiled space adventure yarns (*), Traveller does support grand arcs and epic galaxy-saving quests, but is at its strongest as a career simulator.

Player characters typically start as middle- aged veterans of a military or mercantile career, propelled for whatever reason to become “Travellers.” They then bum around the galaxy, variously treasure hunting, taking mercenary contracts, trading or turning criminal. If they are lucky, they get a spaceship, but then must struggle to make their mortgage payments.

A typical adventure seed as suggested in the old 76 Patrons book would be something like:

A man approaches you in a veteran’s bar. He’s worried that his sister is being held against her will — perhaps kept drugged — by her new boyfriend, an ex soldier from the lower classes who seems to be enjoying high living at her expense. He offers you money to infiltrate her estate and find out what’s really happening…

Options for referee (who can pick or roll a dice as they see fit):

1. Things are as they seem.

2. The patron has it wrong. His sister is having the time of her life with her ‘bit of rough.’

3. The patron is actually the boyfriend and wants to make it look as if you are trying to kidnap the rich lady, thus making her more dependent on him.

4. The sister is actually working for the local Revolution…

5. The patron is a jilted lover.

6. The patron is a stalker.

So, here we have Philip Marlowe but in Space! But equally well it could be, The Bodyguard. And the next adventure might involve looking for a lost scientist on an alien world, or smuggling machine parts to a luddite world, or training a militia, or assassinating a head of state, or just dealing with a local protection racket… yes The A-Team, but with vastly greater body count.

It’s gritty, the combat is lethal, it has its spiritual roots in Kriegsspiel — the pedantic war simulator designed for training Prussian army officers in the 18th century, and the real origin of tabletop wargaming — and, if well refereed, feels real enough to be vivid and addictive.

It’s also just celebrated its 40th anniversary!

Like Dungeons and Dragons, Traveller has been around since the dawn of our hobby. It articulated and inspired a whole subgenre of screen and prose Science Fiction. This is why, having been on a retro-Science Fiction binge for a year or so, I was so keen to review the new edition. It was a return to my own imaginative roots, playing the game nearly four decades ago when I was thirteen.

However, the intro to this article was not me refereeing. It wasn’t even me playing!

Just like in a Country and Western song, we’ve gone full circle and now Kurtzhau, my 13-year-old son has taken up the baton and started to referee… for the first time.

He and I had been play-testing the game. I was refereeing Kurtzhau, Gamer Dad and his son, when one of the neighboring teens dropped by and joined in. An intermediate Warhammer 40K player, this was his first roleplaying experience ever. He liked it so much he sold his twin brother on it. They came around on a rainy Friday afternoon for wargaming but pleaded for Traveller.

“Dad’s too busy writing,” said Kurtzhau, firmly. “I’ll GM.”

And he did.

It was Kurtzhau’s first time behind the screen but he coolly extemporised an adventure on the spot, using the subsector we’d developed together. All afternoon, the flat resounded with imagined small arms, yelling teens, and rattling D6s.

Kurtzhau did a lot better job of refereeing than I did at his age. I know this because suddenly the whole neighbourhood 40K circle are queuing up to play Traveller and he and I are having to use Google Docs to administer our shared sandbox campaign — because, yes, we’re doing this West Marches style.

Later he said, “It’s easy compared to Warhammer 40K“.)

Some games, like FATE Spirit of the Century, define a milieu. Others, like Call of Cthulhu, are entry points to a milieu that exists outside the confines of the rule book.

Traveller is old enough and influential enough to do both.

Sure, Traveller started off as an emulation of mid-20th century gritty Space Opera such as Dumarest — and we really do need a name for that genre — but as the gamers grew up, the tabletop game fed back into the genre. Ask around and you’ll find a lot of SF writers who were once — or still are — Traveller players. You’ll also notice a strange consistency of tropes and equipment across one corner of the genre. Some books — naming no names — read awfully like Traveller adventures, especially when quirky local encounters temporarily derail the main plot. Also, at least two popular gritty space-based SciFi adventure series are known to have been based on roleplaying campaigns for “unspecified” systems…

Traveller has gone through something like eleven (11) editions(*), some of them distinct versions, but all fuelling the mythology around the system. (Yours truly fretted over the earliest edition, then — decades years later — failed to come to grips with the first Mongoose edition. Read the first article in this series.)

There’s also an overwhelming volume of secondary material to accompany the game, including reissues of the original editions, plus a promise of more volumes covering specific domains such as vehicles, spaceships and space combat, mercenary careers, and even building and running mercantile empires.

All this makes it challenging to review a new edition of Traveller.

It’s hard to measure the rule book against a genre that it helped create. It’s hard to rate the presentation of the rules without comparing them to what’s gone before. It’s even harder to judge an apparent gap in coverage: Is this something you should know anyway? Don’t you even understand space science? Read science fiction? Have some conception of military life? Or should you go find an answer on the Internet, or wait for the next supplement?

Other people have tracked the changes since the last edition(*). And Traveller veterans are better placed to judge how the new rules fit into their existing campaigns, or reflect the continuity of the standard 3rd Imperium campaign setting.

Me? I’m going to approach this new edition in its own right. I’m going to do so with a variety of hats, including my Occasional GM Hat, my Dad Hat, and my SF Nerd Hat (in practice these all look very similar).

So, let’s go back to Kurtzhau and his first foray into GMing.

Seeing my 13-year-old son taking his place behind the screen filled me with dadly pride (and a certain sweet melancholy known only to parents). However, the episode also illustrates that Traveller‘s storyverse is still compelling, that its rules still function well, that the new edition — plus referee’s screen! — make an adequate job of presenting them, and that the end result is a robust sandbox that generates good adventures.

The Traveller Storyverse

The Traveller storyverse — the dynamic environment created by its setting and rules — is a galactic sandbox with absolutely no character shields — it even used to be possible to be killed during character generation! Technology is imperfectly distributed, and it’s entirely possible — as we did — to end up using lasers and advanced combat rifles to fend off an ambush by musketeers. Adults can immediately see why this is cool. It emulates subgenres we consume.

However, unlike Kurtzhau — who reads adult SF and is also Firefly, Babylon 5, Farscape, SG1 and Deep Space 9 fan (geek parenting, eh?) — the teenage Traveller-novices hadn’t read any SF or watched much TV SciFi. Being mostly Call of Duty players, they didn’t really have Halo or Mass Effect as reference points. Even so, the setting spoke to them, I think, because it combines gosh-wow Science Fiction tropes with realistic adventures that have some connection to the real world — e.g. crime and trade and insurgency — or at least to books and movies with real-world groundings: for example, if you’ve watched the Jason Bourne movies, Traveller will feel familiar.

The lack of character shields — no Fate Points, no extra rolls — made the setting seem more real, more grown-up, and the experience more tense. (Kurtzhau’s friend asked me why I’d kept going on about how lethal the game was… 10 minutes later a teenaged spaceport mugger nearly knifed to death Kurtzhau’s veteran marine officer.)

The Traveller Rules

Traveller‘s rules function well despite the fact that, except for some careful enhancement (and not counting the D20 version), they have not really changed much in 40 years.

Traveller was always admirably recursive, using only one kind of dice (D6!) and mostly one kind of roll. This stands in sharp contrast to e.g. D&D‘s rambling edifice, and to the 40K rules, which — to an outsider — seem to demand high and low rolls almost randomly! The standard Traveller roll — 2D6 with modifiers, with 8+ as the target — produces a nice probability curve and makes small modifiers (e.g. +1/-1) for skill and attributes significant but not over-powered, since diminishing returns set in.

Traveller is built around mini-games: character generation is really a career simulation game (it’s even possible for your player character to end up in jail!); combat, both ground and space, is a tense gritty wargame in its own right; and the trade rules are so self-contained you can play them solitaire.

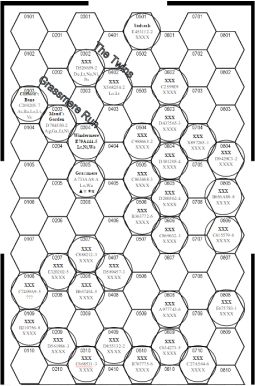

Talking of solitaire, there is something mesmerising about world and subsector generation as an activity in its own right — we did this with paper and pencil, and got hooked. There are also rules for random adventures that generate surprisingly inspiring scenarios.

Back in the 1980s, these mini-games seemed a little odd. We still joke that Traveller is the only game in which characters may not survive character generation! (They do in this version of the rules, but not necessarily with all their body parts intact.) However, nowadays, they make perfect sense.

Character generation, with its rhythm of balancing risk and reward when selecting assignments, is a little similar to games like Elder Sign.

Combat? Modern kids come to roleplaying from wargaming, not the other way around, so the combat rules offer no surprises.

Star trading is a bit like the kind of modern boardgame put out by Fantasy Flight Games — there’s even a Firefly game.

Ironically, world generation resembles some of more narrativist modern roleplaying games or even straight storytelling games. Yes, you roll for just about every feature of your world, but it’s up to you how they tie together. For example, we ended up with Clifford’s Bane, a failing dissent-wracked third-generation artists’ colony occupying an abandoned alien asteroid base unearthed by archaeologists some generations back (the defence systems turned out to be active, and the expedition leader was called Clifford… I’ll let you join the dots).

The rules feel like good simulations.

The ground combat is particularly satisfying. I’ve never — thank the gods! — been in a firefight, but Traveller makes it Saving Private Ryan-grade lethal and handles things like cover fairly seamlessly. For example, there are no actual rules for surpressive fire. However it emerges organically as a result of a target’s successive dodges impacting on their ability to shoot back, and in the option to go to ground and stop returning fire. I find keeping track of initiative scores and hits a bit overwhelming. However, perhaps I’m old, because Kurtzhau does this in his head. We haven’t yet tested the space combat rules, but they seem detailed but straightforward. I expect the result to be more Das Boot or The Hunt for Red October than Star Wars.

Other areas such as the business of spaceship and vehicle operation, and the use of computers, feel realistic and reasonably streamlined as long as you accept that these activities are a focus for game play rather than necessary evils supporting it. The one apparent realism fail is the use of hex maps to represent space as 2D, however this abstraction works fine in practice and can be hand-waved (e.g. “Jump Space is folded like a paper fan, with the galactic hub in the middle.”).

The character generation is both a bug and a feature.

The career minigame seems optimised to produce interesting 40-something screw-ups and spit them out just after their midlife crisis. This produces compelling characters with quirky backstories, such as our ageing scientists who made his big discovery in his 20s but then ended up in admin for most of his career.

However, this is frustrating if you have the urge to play a particular archetype, e.g. a veteran marine, and you can also end up with quite under-powered characters if you are unlucky. This is fine if you enjoy playing against your limitations, but otherwise frustrating, especially for younger players who want to be Han Solo. We ended up with a house rule for “boosted characters,” allowing extra dice in character generation (roll 3 dice and lose the lowest) and two extra survival rolls during your actual career.

The rules are so authoritative that it’s sometimes hard to remember that roleplaying considerations take over where the minigames leave off. For example, the ability to purchase equipment depends on the law and tech level of whatever world you are on. Clearly, what your character can start with will depend on what the referee has in mind.

There are also areas where the core rules would make more sense in conjunction with the supplements. For example, the budgets for guns, blades and armour acquired during character generation are odd, as they are way more than the cheapest tier of kit, but fall short of the really good stuff. Apparently the Central Supply Catalogue has intermediately priced items. Similarly, spaceship design has been dropped from this edition and shifted to the naval supplement, High Guard. However, all this should be no problem as long as you as a referee are firmly resolved that what you have in hand is canon, and everything else outside that scope is up for house ruling or GM fiat.

The Presentation of the Rules

The rules are well written, with a clear idea of the kind of game play Traveller supports. They are also well-illustrated. Kurtzhau in particular appreciated having good visual references for things like survival pods and vac suits.

There are one or two areas where things could be improved. There’s no index (!), some related information is scattered between sections and there are not always cross references, and the character generation has a paragraph of exceptions buried in the text. The game would also be hard to referee without the additional referee’s screen, but that’s probably true of most detailed systems.

However, everything is in good English, a lot of the rules are embodied in the character sheet, and everything makes sense in terms of a self-consistent universe. This means that, though this edition of the rules is not always easy to consult, it is very easy to learn.

The End Result: The Robust and Lively Traveller Sandbox

Though there are many, many campaigns available for Traveller, and though it does support grand arcs and sweeping adventures, for me the mesmerizing power of the game lies in its ability to function as a sandbox.

You really can dump your player characters onto a world and just kick off a random or extemporized adventure that will feel satisfying to play, and somehow, through iron-man simulationism, generate a story that you will subsequently retell as if it were real: Remember that time we were hired to sneak a hi-tech bathroom facility into a luddite High Patriarch’s winter retreat but it was a set up and these musketeers wrecked our truck but couldn’t penetrate our body armor and…

Traveller manages this through its top-down “world” building.

You don’t start off with an adventure and work up to the setting through improvisation. You start off with a world, generated according to the instructions in the worldbuilding chapter, which works a bit like procedurally generated space exploration video games, e.g. the original Elite. This extrudes the bones of the setting so that they relate to each other in ways that make sense. For example, planetary government type, law level and technological level are all interrelated. The result is very robust indeed, without any sense of being railroaded.

This robustness means that it would be very hard for the native of any given world to break the setting… which of course is where the Travellers come in.

Traveller worlds naturally generate plot because they come with conflict built in.

For a start, the interrelationship between world characteristics has a way of embroiling characters. For example, take just Tech Level and Law Level. Generally, but not always, the higher the former, the more restrictions from the latter. The world with the best weapon technology is the often the one where weapons are the most restricted. Conversely, on lawless worlds where self-help is the order of the day, Travellers are likely to find themselves amongst the better-armed individuals, and thus tempted by various contracts or pleas for help. There are also rules for generating political factions and cultural quirks — all likely to spawn missions or dangerous interactions. Finally, random encounters and optional random adventure seeds directly generate conflict for the players.

The end result is a highly playable game that transports you to its setting. The rules are not the simplest to play, but they are easy to master because they make sense. I shall certainly be playing Traveller for years to come, as will — I suspect — my son and his friends.

Ultimately, through attention to detail and meticulous world building with adventure baked in, Traveller has always achieved something special. By focusing the gameplay on the challenges of operating, or merely staying afloat, in a gritty Science Fiction universe, it puts you there, in the picture, in a firefight in a bar on a low-G world, or bringing your merchant ship down on some backwater planet where you hope to earn enough to pay off some missed installments but then encountering pirates…

The new Mongoose Traveller Core Rule Book is a worthy successor to this tradition. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be taking a closer look at its specific sub systems, and also considering its underlying logic and themes. (Watch out for the next article: What’s Traveller Actually About?…)

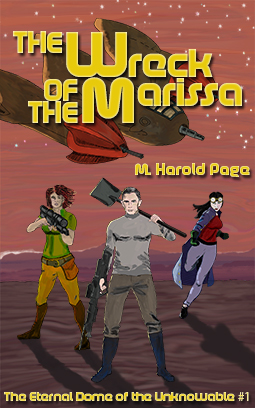

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of The Wreck of the Marissa (Book 1 of the Eternal Dome of the Unknowable Series), an old-school space adventure yarn about a retired mercenary turned archaeologist. He’s on a quest to find the mythical Dome but keeps getting involved in “local difficulties”. You can get it here.

Fantastic comprehensive review!

The first edition Traveller also lacked any real character advancement rules, so the character generation mini-game was almost an end game, in itself. I lost many a character pre-play in order to get a decent PC “traveller”.

Of course, there were also ways to “game” the chargen mini-game. I found that being a Naval character who was Pilot of a capital ship made death so unlikely that really outrageous survival modifiers (down to -3) could be chosen, with subsequent honors (up to +3) modifiers making the character into the Audie Murphy of the Spinward Marches.